Click here to download a zip file with a printable PDF of notation and MP3s to practice offline.

Are you ready to inject some “soul” into your jazz playing? “Soul jazz” is a sub-genre of jazz that became prominent in the late 1950s with the arrival of the Hammond B-3 organ. Jazz clubs were beginning to install “in-house” organs, and such artists as Jimmy Smith created a new ensemble—the organ trio—to perform in these venues. This ensemble generally consisted of organ, guitar, and drums, but also included a horn player or two on occasion. Because of the more groove-oriented sound and styling of this “new” ensemble, which placed a high emphasis on slower tempo shuffles and the 12-bar blues progression, the soul jazz genre was born and rose to popularity during the ’50s and ’60s. In this Style Guide, we’re going to examine concepts to help put you on the path to playing some righteous soul jazz!

We will focus on comping concepts—guide tone voicings, the “Charleston” rhythm, and four-note block chord voicings. We’ll also examine such improvisational devices as three-note repetitive patterns, organ-like double-stop licks, Grant Green-style “turns,” and octave/block chord call-and-response.

I’ve compiled a sample list of guitarist and organist teams I associate with the soul-jazz genre. In no particular order, these are classic groups that are sure to inspire you to further explore soul jazz.

- Grant Green with organists “Baby Face” Willette and Larry Young

- George Benson with organists Jack McDuff and Dr. Lonnie Smith

- Kenny Burrell with organist Jimmy Smith

- Pat Martino with organists Jack McDuff and Trudy Pitts

- Wes Montgomery with organist Melvin Rhyne

- Peter Bernstein with organists Larry Goldings and Melvin Rhyne

Comping

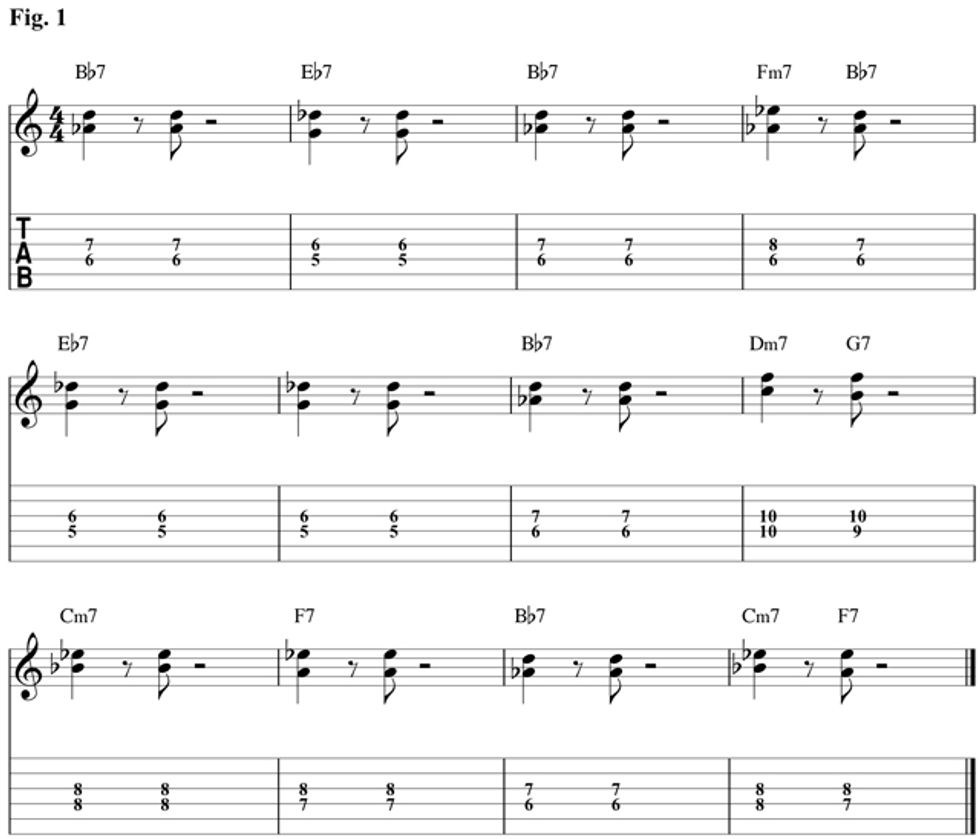

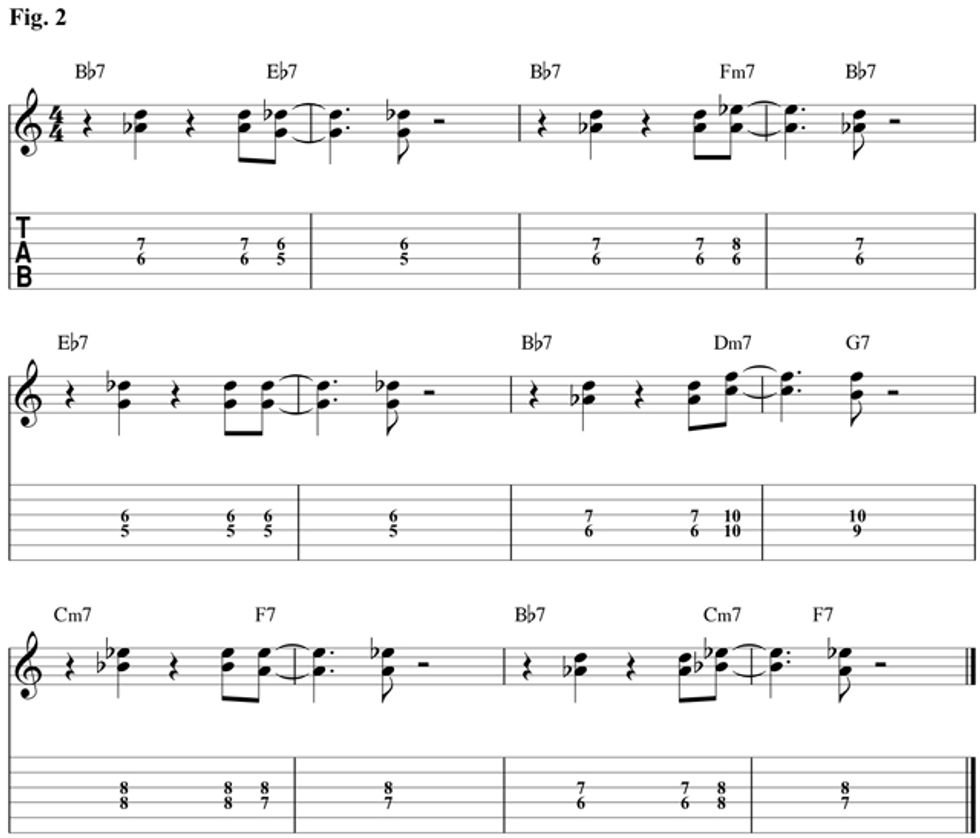

While the art of soul-jazz improvisation is the main focus of today’s lesson, it is also important to have a good base of comping ideas in your musical bag. Fig. 1 takes simple two-note guide-tone voicings (harmonic structures built using only the 3rds and 7ths of each chord), and incorporates the Charleston rhythm. The latter is a fundamental rhythm all jazz musicians should master. This rhythm is played on the downbeat of beat 1 and the “and” of beat 2. This is an especially useful comping pattern in soul jazz, and was employed extensively by guitarist Grant Green (check out “Miss Ann’s Tempo” on Grant’s First Stand). Be sure to listen and play along with the recorded example to get the sound and feel in your ear! This comping style is not specific to the 12-bar blues, and can be used on any and all of your favorite jazz tunes.

Fig. 2 builds on the guide-tone voicings in Fig. 1. However, we’re now adding a new rhythm to the mix. Playing the same comping rhythm over and over can become boring for musicians and the audience, so I encourage you to continue adding new rhythms through experimentation, and, most importantly, by listening to the jazz-guitar masters I listed previously.

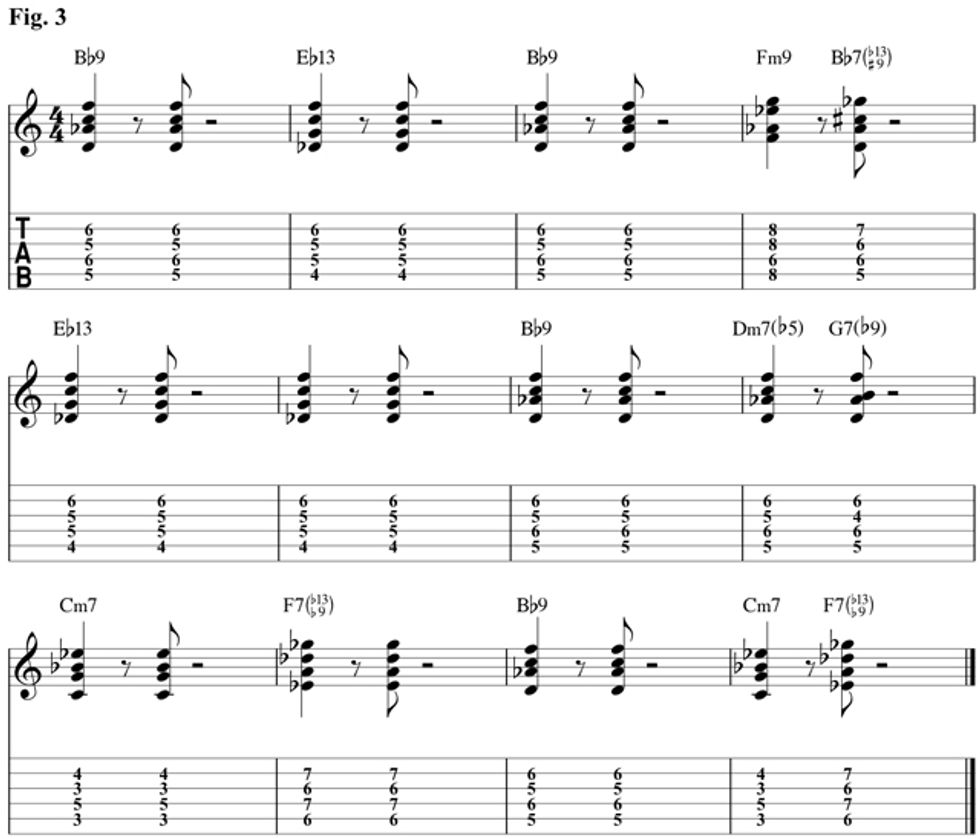

We are now going to revert back to the Charleston comping rhythm, but in Fig. 3 we are going to employ four-note block chord voicings. Specifically, we are going to use “drop 2” voicing structures. While guitarist Grant Green had a penchant for using the guide tone voicings of Fig. 1, guitarists such as Pat Martino and George Benson used larger voicings to generate a fuller sound when comping behind an organist. These voicings are useful in soul jazz, but again, can be used in any jazz style. The voicings in Fig. 3 allow you to use the 3rds and 7ths of the chords, while also achieving 7th-chord alterations, such as b9, #9, and b13.

Now that we have some comping ideas under our belts, it’s time to turn up the heat and get ideas that are sure to add some soul to your own improvisations!

Improvisation

Soul jazz is based heavily on the 12-bar blues progression, but this progression deviates slightly from the traditional I–IV–V blues we all know and love. The main difference is the addition of the IIm7–V7–I7 progression. This progression occurs a whopping four times—in measures 4, 8, 10, and 12—in this jazz version of the 12-bar blues. Because of this added harmonic complexity, it is incredibly important to gain familiarity with ideas that work over this crucial progression.

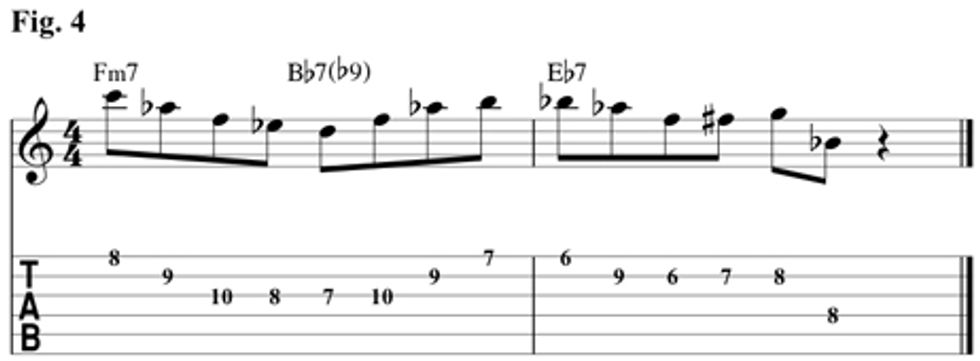

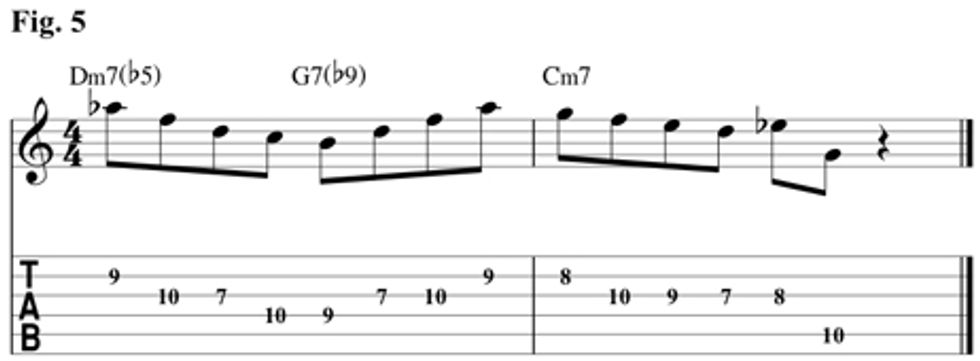

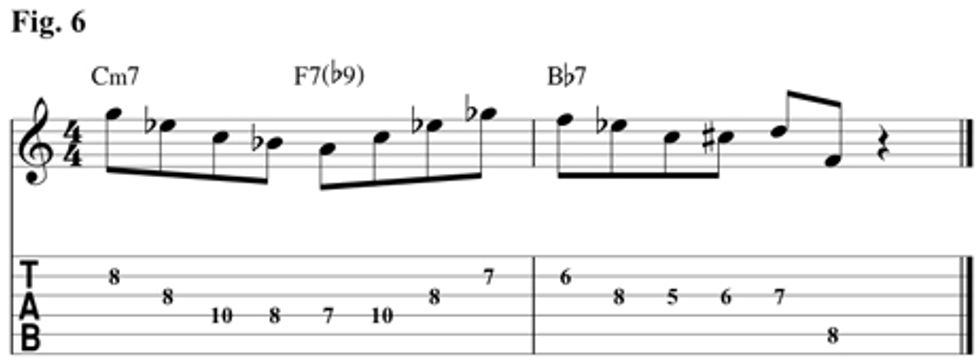

Fig. 4, Fig. 5, and Fig. 6 consist of a simple idea that makes use of 7th-chord arpeggios over the progression. These examples cover the three key centers you’ll encounter in the blues progression. This idea, initially codified during the bebop era, can be heard in a vast amount of recorded jazz solos and is not specific to the guitar.

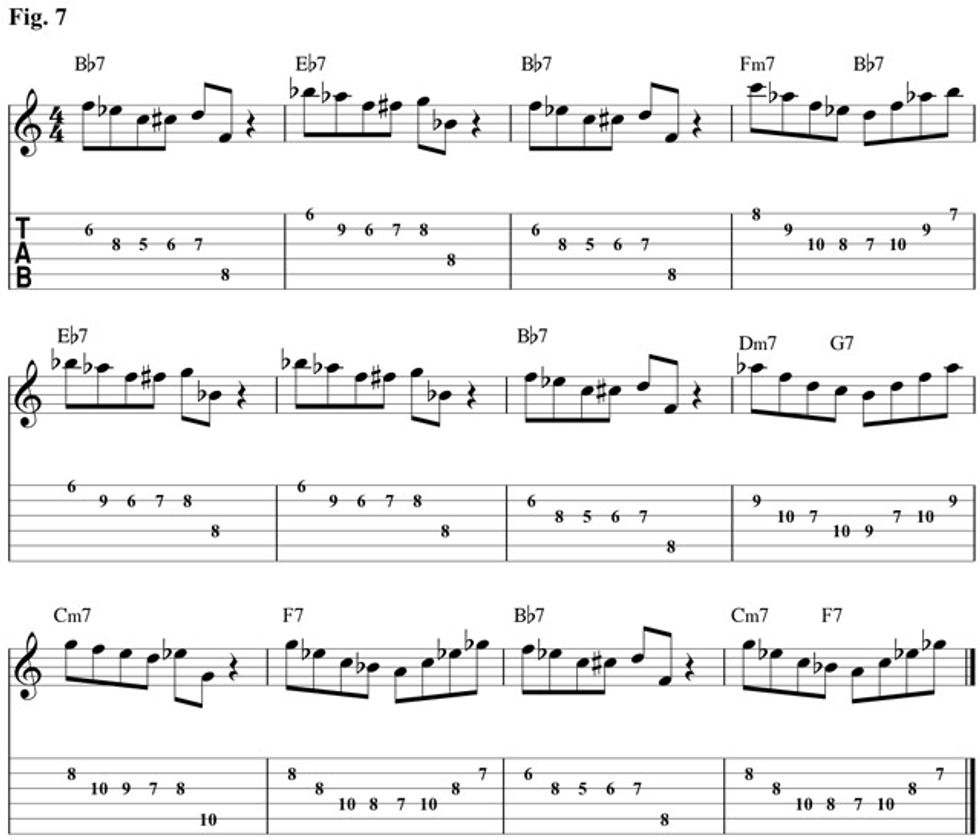

Once you gain some technical fluency with these licks, it’s time to incorporate them over the entire blues progression. This can prove to be a bit tricky at first, but once you get a handle on the idea it will become second nature in no time. When playing through Fig. 7, it is helpful to think of the two-measure licks in Figures 4, 5, and 6 as two separate licks. Fig. 7 takes the second measure of the lick in Fig. 4 and breaks it up so you have something to play over each chord that isn’t a part of the IIm–V7–I7 progression. Gaining technical proficiency with this idea will help take your playing to the next level.

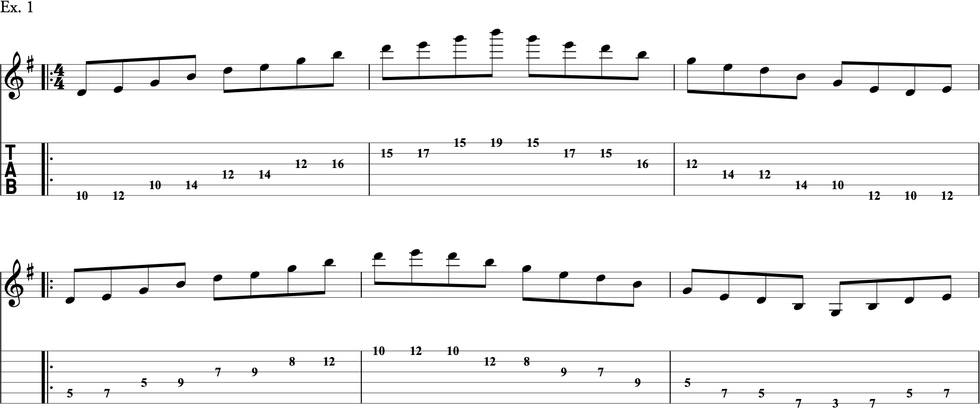

Now that your IIm–V7–I7 language is gaining momentum, let’s switch gears and look at some repetitive patterns. Playing a repetitive motif can generate excitement during an improvised solo, and the recurring nature of these phrases offer other rhythm section members an opportunity to react. Pat Martino and George Benson are masters of this technique.

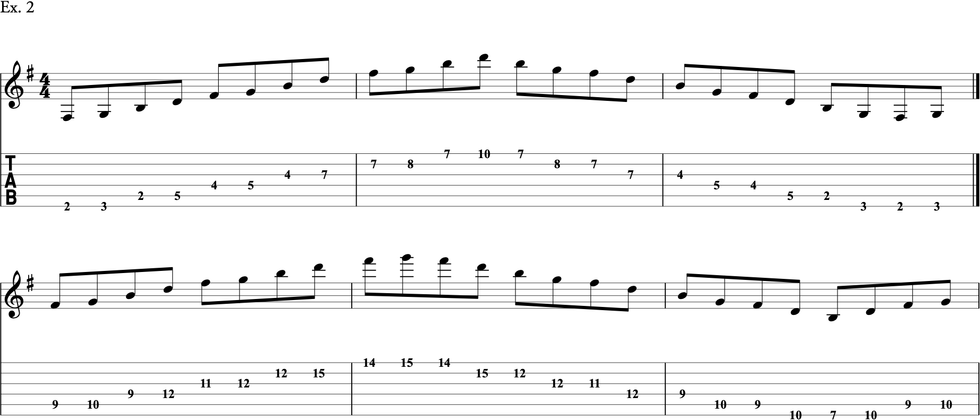

Fig. 8 is one such repetitive pattern. As you will see, I have placed the pattern in four different areas on the guitar neck. The fourth example also changes the shape and includes a different articulation of the phrase. I have included some suggested articulations (hammer-ons/pull-offs/slides), but these are only suggestions. It’s an important part of the process to find your own ways to articulate repetitive patterns.

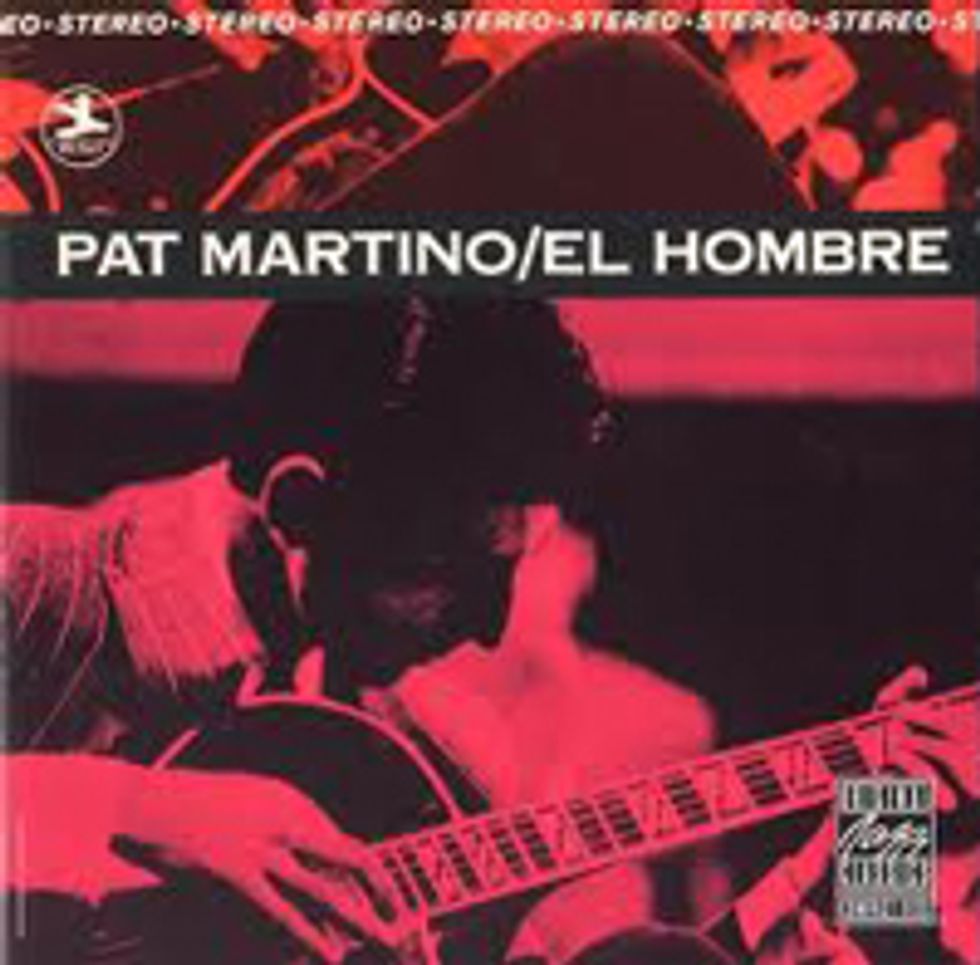

Before moving on, check out Pat Martino improvising on “A Blues for Mickey-O” from his classic album, El Hombre. You will hear a lot of the improvisational material we are about to discuss.

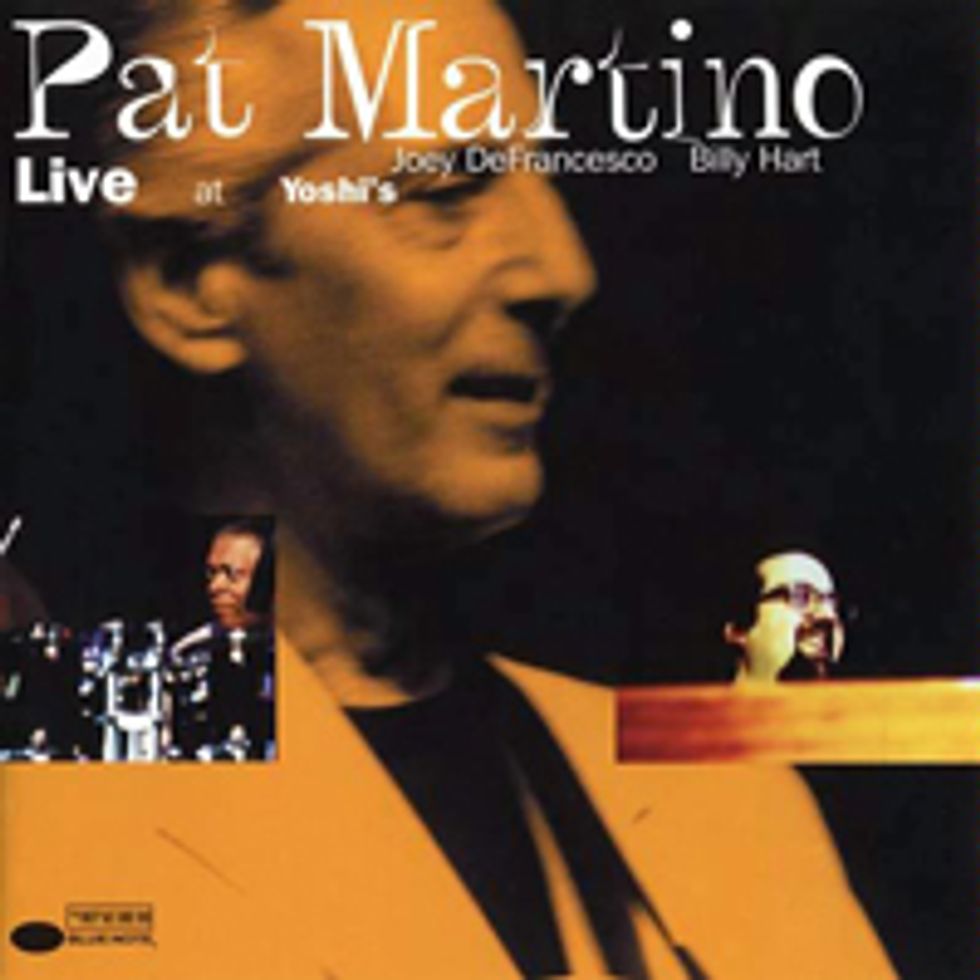

Also, be sure to check out the video of Pat Martino on “All Blues” from Live at Yoshi’s. This solo is a textbook example of these types of repetitive patterns.

Experiment with each of the four repetitive pattern variations in Fig. 8. Each variation could be played over an entire chorus of blues.

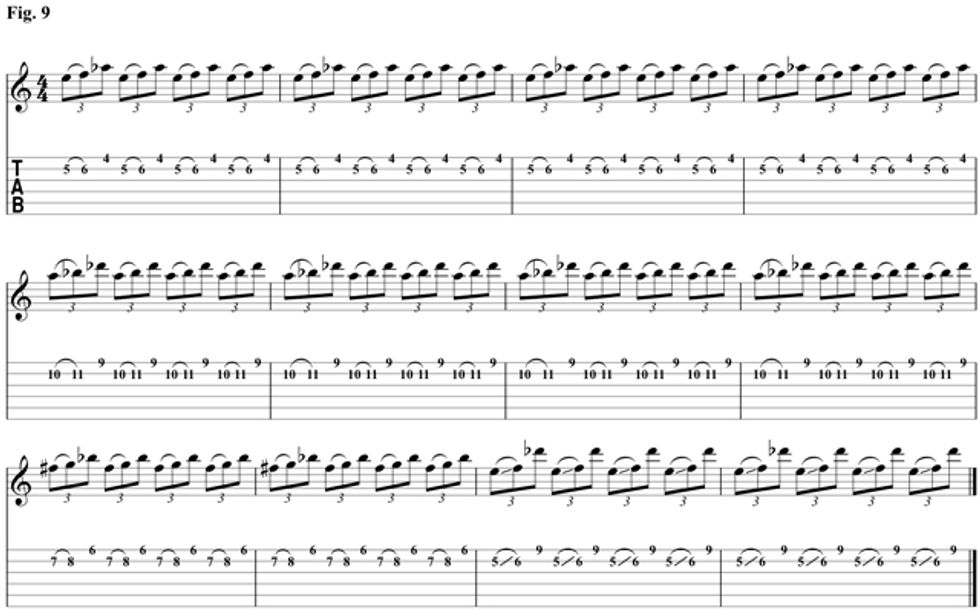

Fig. 9 shows one possibility of using all four three-note patterns over a chorus of blues. But remember, don’t just practice my examples, experiment with different combinations to make this idea your own. Initially you should practice this example with the given articulations. Once you feel comfortable, try varying your right- and left-hand phrasing. One possible way to vary the articulation is to pick every note rather than using hammer-ons and slides.

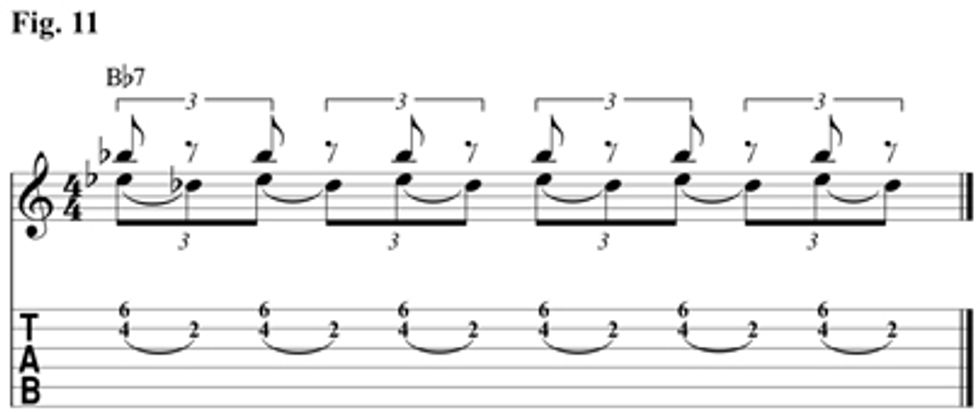

Fig. 10 and Fig. 11 illustrate double-stop ideas that an organist might play in the soul jazz genre. Hammond B-3 players are able to sustain one top note in their right hand while improvising counter lines with their left hand. Since we only have the capability of using our left hand on the fretboard (at least when using traditional techniques), I have adjusted the concept to work on the guitar. Play through both examples while focusing on sustaining the top note. Pat Martino uses the lick in Fig. 11 during his improvised solo on “A Blues for Mickey-O.”

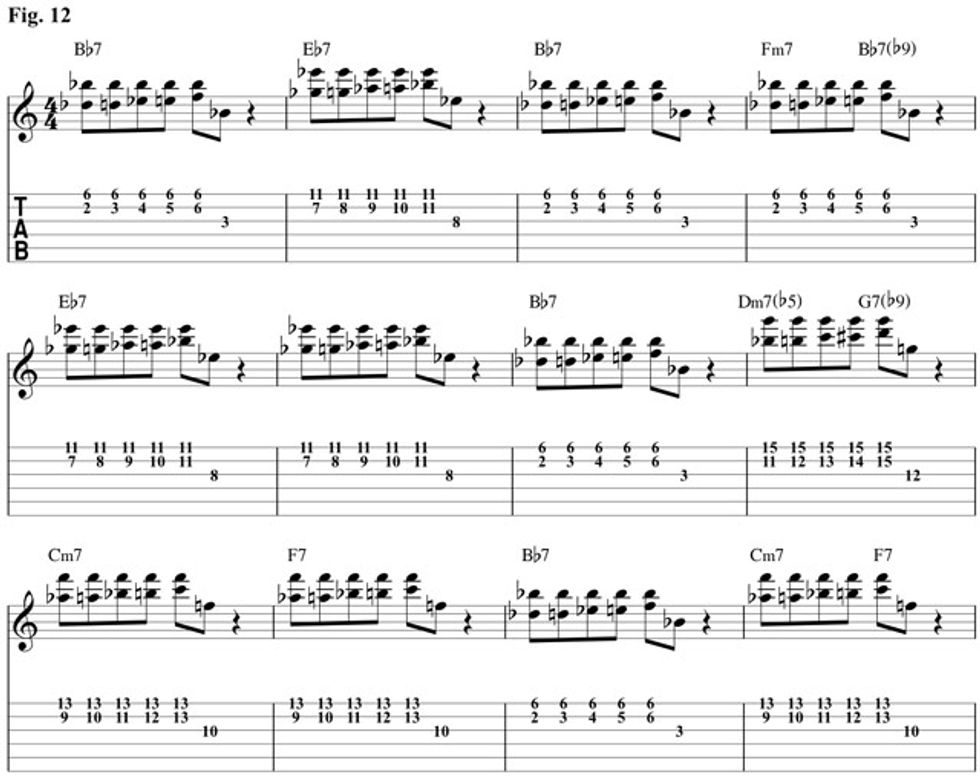

Fig. 12 illustrates the use of both of these ideas over a blues progression. The first chorus uses Fig. 10 extensively, and the second chorus employs the idea in Fig. 11. In the first chorus I have taken the idea and adjusted the placement to fit over the changing harmonic motion. I would suggest extra practice time on the first chorus, as it is more involved.

Now we are really getting somewhere! Before proceeding to the next idea, I would strongly suggest exploring each of the previous patterns over the provided play-along tracks. Both tracks are Bb blues progressions at a relaxed tempo, and they’ll allow you to really dig in and investigate your own amalgamations of these patterns.

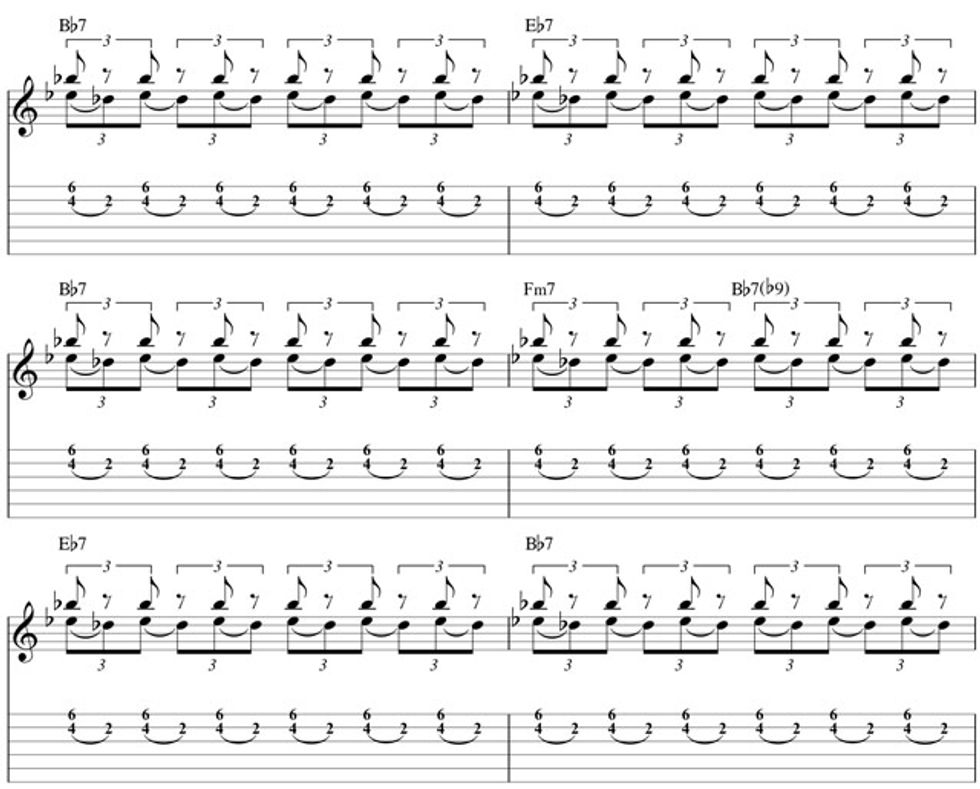

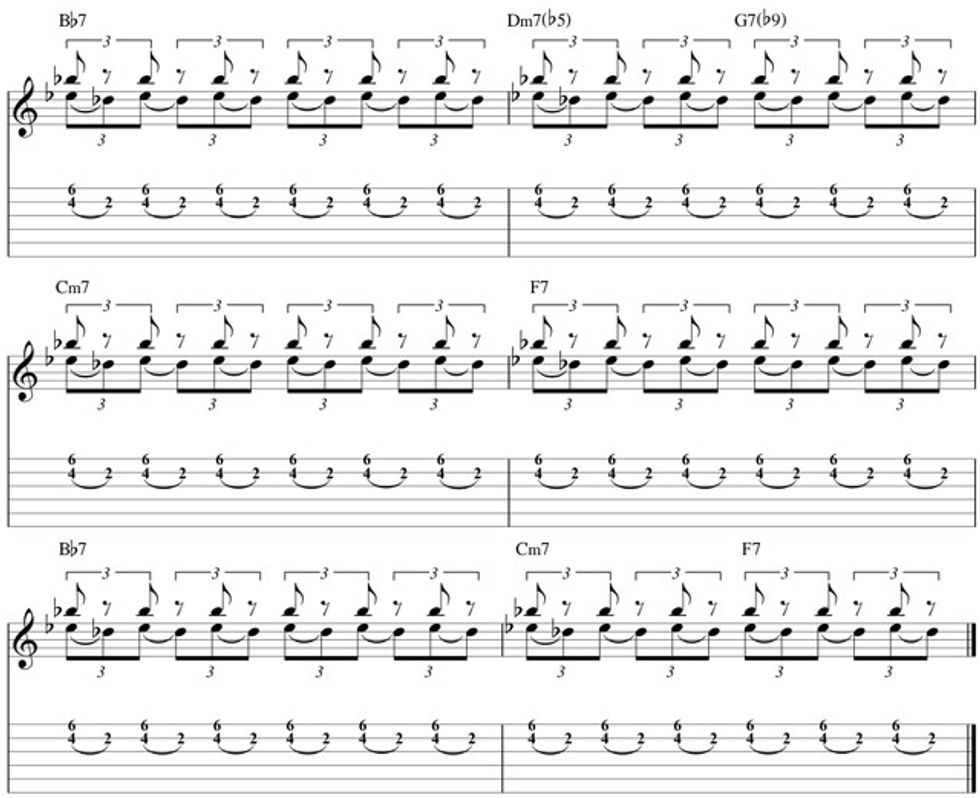

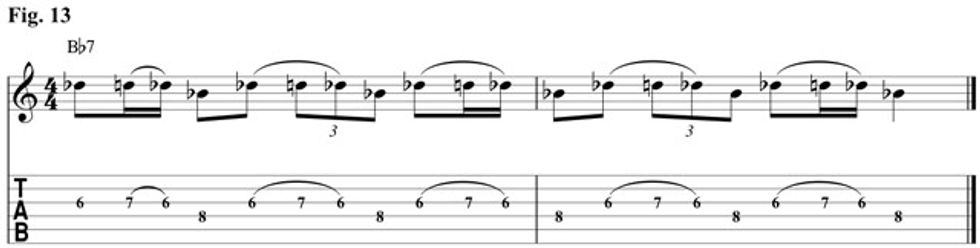

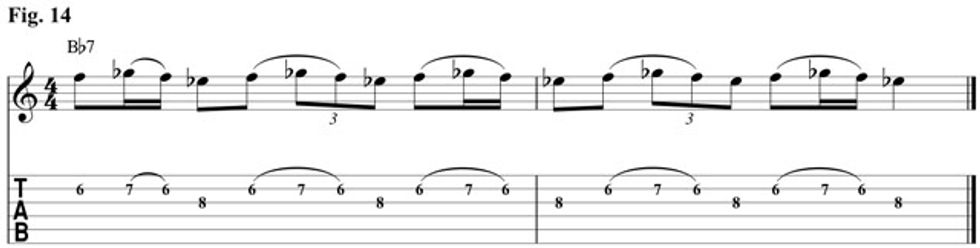

Moving right along ... the next pattern is out of the Grant Green book of soul-jazz guitar improvisation. It is a simple repetitive pattern that can be used over an entire chorus of blues. I refer to these as “turns.” The written rhythm makes it look more complex than it actually is, so I encourage you to listen to the recorded example in order to capture the correct feel of the idea. Before diving into Fig. 13 and Fig. 14, check out Grant Green playing “Surrey with the Fringe on Top.” It’s not a blues progression specifically, but at 1:23 you’ll hear the master himself demonstrate what these turns should sound like.

Pay close attention to the articulations, and work toward capturing a relaxed—almost lazy—feel on the pull-offs. Practice each example separately over the blues progression, then experiment with various combinations of these two patterns.

Fig. 15 simply makes use of the idea in Fig. 13 over an entire chorus of Bb blues. This really swings when played correctly, and can be used at any tempo from fairly slow to burning!

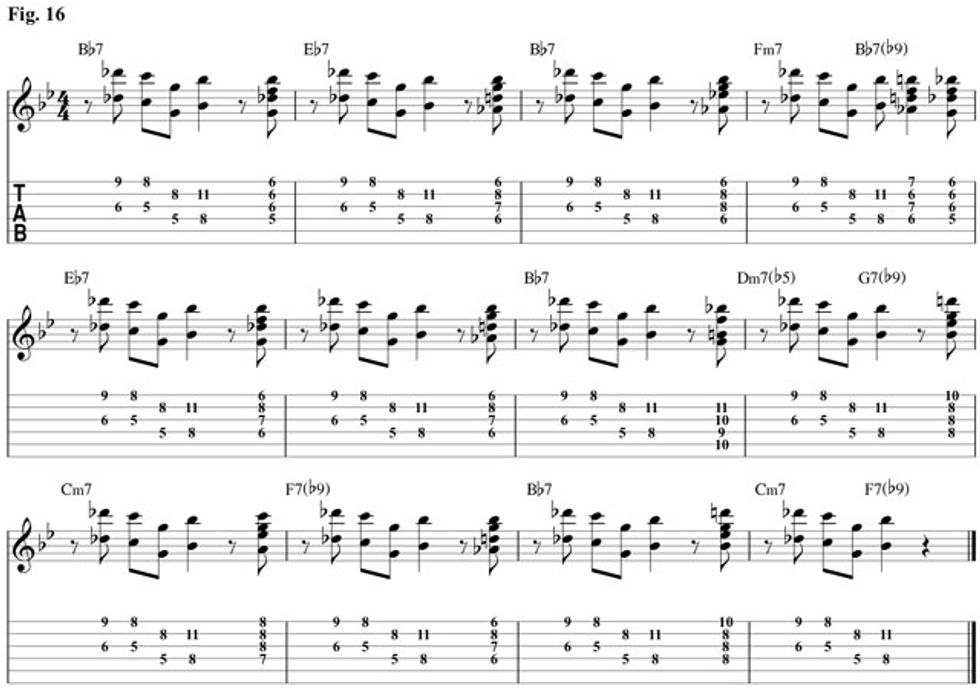

The final concept we will examine in today’s lesson is the blending of octaves with four-note block chord voicings. The chord voicings are similar to what we looked at earlier in Fig. 3. Mixing these two devices in an improvised blues chorus is a great way to add some spice to your improvisations. Employing the following idea gives the guitarist a call-and-response type of sound and blurs the lines between straight-up improvisation and comping. This can also create the aural illusion of two guitars playing at the same time.

Wes Montgomery was the master at applying this idea, and I highly encourage you to check out Wes if you haven’t already. In fact, before proceeding, take a minute and check out this video of Wes playing a blues in F. He uses the specific octave and four-note block concept beginning at 3:54, but watching the entire video is sure to inspire even the most advanced jazz musician.

Fig. 16 utilizes the octave and four-note block chord blend, and is an idea that will invoke the sound of Wes in your own blues improvisations. The key to the call-and-response aspect of this idea is to play short octave motifs that are punctuated with block chord “stabs.” This idea is sure to generate excitement!

If you have made it this far, give yourself a pat on the back as we have covered a lot of ground in the soul-jazz genre. Give yourself a chance to rest while watching these two videos of Peter Bernstein and George Benson. While watching and listening, focus on hearing materials similar to what we have worked on in this lesson.

I hope you have enjoyed working through this lesson as much as I have enjoyed putting it together. We have only scratched the surface of soul-jazz comping and improvising, but I truly hope that this material has inspired you to get a bit more “soul” in your jazz playing!

Suggested Discography

Recorded in 1967, this is Pat Martino’s first album as a leader. It’s hard to believe Pat was only 22 at the time. It also features Trudy Pitts, a highly underrated Hammond B-3 organist from Philadelphia. This is soul jazz at its finest. Highlights include “A Blues for Mickey-O” and “Just Friends.”

A live record showcasing Pat Martino’s beautiful lines, exciting repetitive motifs, funky organ double-stop licks, and incomparable technique, the album also features organ phenom Joey DeFrancesco. Highlights include “Oleo,” “All Blues,” and “Mac Tough.”

This funk-laden record was recorded in 1967 for Blue Note, and features a young George Benson on guitar as well as Lonnie Smith on Organ. Alligator Bogaloo showcases some incredible riffing from Benson, especially on “Alligator Bogaloo” and “The Thang.” If you want to learn how to apply the blues scale in your jazz improvisations this is a great place to start. Lou Donaldson also plays some killer bop lines throughout this record.

Recorded in 1959, A Dynamic New Sound features Melvin Rhyne on organ and Wes Montgomery at his finest. This record is filled with numerous examples of not only Wes’ superb single-note soloing, but also his masterful use of octaves and block chords as part of his improvisations. Highlights include “Jingles” and Wes’ beautiful rendition of the classic ballad “Too Late Now.”

Boss Guitar, recorded in 1963, is another fine demonstration of Montgomery’s skill in the soul-jazz genre. Highlights include “Besame Mucho” and “Fried Pies.” In the latter, dig Wes’ skillful chord work in the melody.

Grant’s First Stand, Green’s 1961 Blue Note debut, features the guitar/organ tandem of Grant Green and “Baby Face” Willette. This record exemplifies Green’s unique blend of swinging bebop licks and mesmerizing soul-jazz concepts. Throughout the album Green makes use of guide-tone voicings and “turns” discussed in our lesson. Highlights include “Miss Ann’s Tempo” and “Lullaby of the Leaves.”

Saxophonist Lou Donaldson “discovered” guitarist Grant Green and was responsible for Green’s position as house guitarist for Blue Note Records in the early 1960s. Here ’Tis, recorded in 1961, is another fine example of Green’s fusion of bebop and soul jazz. Highlights include “A Foggy Day” and “Cool Blues.”

The title says it all! Benson is “cooking” throughout this recording, featuring Lonnie Smith on the organ. This is a “desert island” type of record, so do yourself a favor and check it out. Highlights? The entire album ... Benson tears it up throughout.

Recorded in 1964, The New Boss Guitar of George Benson is his debut as a leader. This recording showcases Benson, only 21 at the time, paired with organ legend Jack McDuff, and Benson is on fire throughout. The New Boss Guitar showcases his burning single-note runs, adroit chord work, and blues drenched soul-jazz riffs. Highlights include “Will You Still Be Mine?” and “Rock-A-Bye.”

Arguably one of the most popular soul jazz recordings of all time, Back at the Chicken Shack pairs two legends of the guitar and organ, Kenny Burrell and Jimmy Smith. Burrell and Smith are also joined by soul jazz saxophone legend Stanley Turrentine. This record contains all of the grease of a good home-cooked Southern meal, and the title track typifies the soul-jazz genre. The album features some of the finest solos ever recorded by Burrell, and Burrell’s comping on “Back at the Chicken Shack” is superb. Highlights include “Back at the Chicken Shack” and “Messy Bessie.”

Peter Bernstein is a member of the new school of soul-jazz guitarists and this video is a must have any soul jazz enthusiast. Bernstein’s relaxed, swinging style exemplifies a guitarist who has digested all of the soul-jazz language set forth by Green, Montgomery, Burrell, and Benson. Live at Smoke also features the dazzling organ work of Larry Goldings. Highlights include “Jive Coffee,” “Puttin’ on the Ritz,” and “Bobblehead.”

Click here to check out songs from these albums on our Spotify playlist!

Shawn Purcell is a jazz guitarist in the Washington D.C. area, and is a member of the United States Naval Academy Band. For more information, go to shawnpurcell.com.