Over the past few months,

I’ve discovered quite a

few things, thus proving the

old adage that you’re never too

old to learn. Reading is meant

to accomplish “the four Es”—enriching, enlightening, entertaining,

and educating—and in

that spirit I’d like to share five

lessons I’ve recently learned.

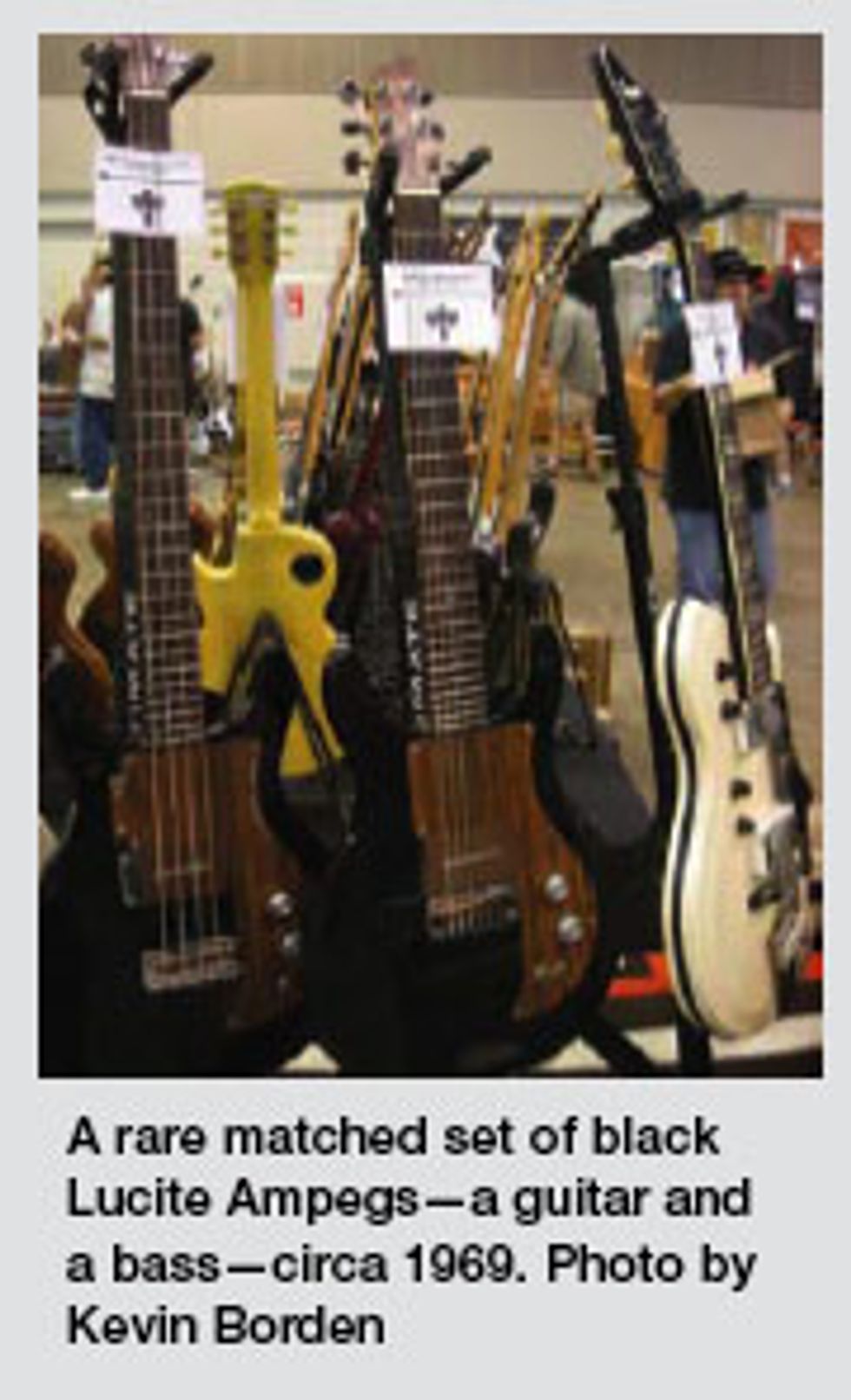

My first lesson—which was provided by Elliot Michael of Rumble Seat Music—concerns a circa-1969 Ampeg Lucite bass. A lot of us already know about the Ampeg Lucite bass and its quirks—its clear Lucite body that weighs a ton, the fact that it has the weirdest scale length on the planet, and how impossible it is to intonate due to its Danelectro-style bridge with a one-piece wooden saddle.

At the Arlington Guitar Show, I walked into Elliot’s booth to see a matched set of Lucite Ampegs—a guitar and a bass—in see-through black. Staring at these instruments, I thought, “Wow, those are very cool modern repros!” I’m the bass guy who has supposedly seen it all, but I was quickly educated: They were real-deal, original issue. I did not know black Lucite basses were ever made!

The bass had a few prototypical features that made it even more intriguing. There was a scoop in the body to facilitate pickup swapping—something I’d never seen on an original Lucite Ampeg bass. It also had a chrome tab screwed to the body covering the scoop. Further, it didn’t have as sharp of a ridge on the body as the standard basses. This was the coolest bass in the show. When I asked my bass buddies if they saw this Ampeg, they all replied, “You mean the reissue?”

My second lesson concerns beer and Rickenbackers. What does beer have to do with bass playing other than saving you from jamming knitting needles into your eardrums when you hear a lousy player? The answer comes courtesy of Andrew Southern of Brooklyn, New York, who points out that Grolsch beer bottles with the porcelain swing top have a red rubber gasket that works perfectly as a strap lock over your Rickenbacker’s strap button! Grab two and rest easy—they won’t mar the finish because they rest on your strap. Unlike a metal-button system, they’re not 100 percent foolproof, but none of those store-bought locks will fit your old Ricky without destroying its strap-pin hole. This is a neat tip and it’s free (other than your bar tab).

And my third lesson revolves around 1960s Fender mother-of-toilet-seat pickguards. Fender started to use mother-of-toilet-seat (aka MOTS) for either their back layer or top and back layer of the multi-ply pickguards in the mid to late ’60s. These guards were notorious for their destructive tendencies on Telecaster basses (which had MOTS in the back layer). Mustang basses used MOTS as the face and back layers. A cool thing the plastic does is change color over time. Most of the time it turns amber. Occasionally it turns orange, green, or even pink. At the Arlington Show, a dealer tapped me on the shoulder and said, “Did you see the 1970 Competition Orange Mustang bass?” Yes, I had. The dealer continued, “Too bad about the repro ’guard, huh?” The ’guard looked repro, but it was not. It had turned violet and it was 100 percent original. You just never know what you are going to see!

Lesson four: Not all Ernie Ball Music Man parts are interchangeable. Yes, this was another “Arlingtonism.” A dealer walked to my booth and offered me a trade for his tidy Mocha B00 StingRay. Maybe I was bleary-eyed from going to see the Yankees in Game 1 of the ALCS, or maybe it was instinct, but the bass struck me as non-Kosher. Early StingRays have a funny sideways break angle over the saddles. That issue was rectified about two years into production. Now, here’s what I learned from this bass: While the bridge assemblies are interchangeable, they do not fit the respective models. The bass at hand was in reality a B01 or a B02, and someone had switched the neck plate and bridge on it. The problem is, while the bridge bolts up, the string-through holes between the bridge and body do not match. As a result, you cannot feed strings through the body. What the prior owner had to do was feed the strings through the body, then bolt the bridge plate down, and finally string and tune the bass. The strings were essentially locked in place. Do not pass go, do not collect $2000!

My fifth lesson was discovering an essential book. As I travel the country, I meet scores of wonderful people. All are enthusiasts, many are players, and some are collectors. All these folks can back up their work. I also meet a lot of authors, many of whom do a really good job. They create a product and shop their work to publishers, but—as with music—very few “make it.” A few years ago, I met Detlef Schmidt, who is a Precision bass aficionado and has a passion for the early “cowboy plank” basses. At the time, he wanted to feature a 1951 that I co-own in his book, but I am very private about my stash, as is the instrument’s other owner.

At Arlington, Detlef presented me with a hardcover copy of his book, which I was flattered to receive. Fender Precision Basses: 1951-1954 is by far the best single-source knowledge base on this topic. The book is gorgeous. The research is dead-on accurate. The photography is perfect. This is a must-have from the knowledge perspective alone. One superb aspect of the book is that it’s written “registry” style. Detlef tracked down as many of these basses as possible, documented them, and presented the results in serial-number order. The way he captured this info is compelling, and he shows many typical modifications that occurred in the ’60s and ’70s. This is an excellent and honest presentation of all things original and modified relating to early-’50s P basses.

Learning is one of the great things in life, especially when it’s about a topic you love. All this new information came to me in a barrage that I could not wait to share, and I hope you enjoyed it.

In our next installment, I’ll discuss the influential changes I’ve seen from a vintage-bass viewpoint. With my 49th birthday past and my 50th on the horizon, my report will cover quite a stretch of time. A lot has come and gone during those years, so I hope you’ll check it out. See you then.

Kevin Borden has

been playing bass since

1975. He is the principal

and co-owner, with

“Dr.” Ben Sopranzetti, of

Kebo’s Bass Works (visit

them online at kebosbassworks.com). You can reach Kevin at

kebobass@yahoo.com. Feel free to call

him KeBo.

Kevin Borden has

been playing bass since

1975. He is the principal

and co-owner, with

“Dr.” Ben Sopranzetti, of

Kebo’s Bass Works (visit

them online at kebosbassworks.com). You can reach Kevin at

kebobass@yahoo.com. Feel free to call

him KeBo.

My first lesson—which was provided by Elliot Michael of Rumble Seat Music—concerns a circa-1969 Ampeg Lucite bass. A lot of us already know about the Ampeg Lucite bass and its quirks—its clear Lucite body that weighs a ton, the fact that it has the weirdest scale length on the planet, and how impossible it is to intonate due to its Danelectro-style bridge with a one-piece wooden saddle.

At the Arlington Guitar Show, I walked into Elliot’s booth to see a matched set of Lucite Ampegs—a guitar and a bass—in see-through black. Staring at these instruments, I thought, “Wow, those are very cool modern repros!” I’m the bass guy who has supposedly seen it all, but I was quickly educated: They were real-deal, original issue. I did not know black Lucite basses were ever made!

The bass had a few prototypical features that made it even more intriguing. There was a scoop in the body to facilitate pickup swapping—something I’d never seen on an original Lucite Ampeg bass. It also had a chrome tab screwed to the body covering the scoop. Further, it didn’t have as sharp of a ridge on the body as the standard basses. This was the coolest bass in the show. When I asked my bass buddies if they saw this Ampeg, they all replied, “You mean the reissue?”

My second lesson concerns beer and Rickenbackers. What does beer have to do with bass playing other than saving you from jamming knitting needles into your eardrums when you hear a lousy player? The answer comes courtesy of Andrew Southern of Brooklyn, New York, who points out that Grolsch beer bottles with the porcelain swing top have a red rubber gasket that works perfectly as a strap lock over your Rickenbacker’s strap button! Grab two and rest easy—they won’t mar the finish because they rest on your strap. Unlike a metal-button system, they’re not 100 percent foolproof, but none of those store-bought locks will fit your old Ricky without destroying its strap-pin hole. This is a neat tip and it’s free (other than your bar tab).

And my third lesson revolves around 1960s Fender mother-of-toilet-seat pickguards. Fender started to use mother-of-toilet-seat (aka MOTS) for either their back layer or top and back layer of the multi-ply pickguards in the mid to late ’60s. These guards were notorious for their destructive tendencies on Telecaster basses (which had MOTS in the back layer). Mustang basses used MOTS as the face and back layers. A cool thing the plastic does is change color over time. Most of the time it turns amber. Occasionally it turns orange, green, or even pink. At the Arlington Show, a dealer tapped me on the shoulder and said, “Did you see the 1970 Competition Orange Mustang bass?” Yes, I had. The dealer continued, “Too bad about the repro ’guard, huh?” The ’guard looked repro, but it was not. It had turned violet and it was 100 percent original. You just never know what you are going to see!

Lesson four: Not all Ernie Ball Music Man parts are interchangeable. Yes, this was another “Arlingtonism.” A dealer walked to my booth and offered me a trade for his tidy Mocha B00 StingRay. Maybe I was bleary-eyed from going to see the Yankees in Game 1 of the ALCS, or maybe it was instinct, but the bass struck me as non-Kosher. Early StingRays have a funny sideways break angle over the saddles. That issue was rectified about two years into production. Now, here’s what I learned from this bass: While the bridge assemblies are interchangeable, they do not fit the respective models. The bass at hand was in reality a B01 or a B02, and someone had switched the neck plate and bridge on it. The problem is, while the bridge bolts up, the string-through holes between the bridge and body do not match. As a result, you cannot feed strings through the body. What the prior owner had to do was feed the strings through the body, then bolt the bridge plate down, and finally string and tune the bass. The strings were essentially locked in place. Do not pass go, do not collect $2000!

My fifth lesson was discovering an essential book. As I travel the country, I meet scores of wonderful people. All are enthusiasts, many are players, and some are collectors. All these folks can back up their work. I also meet a lot of authors, many of whom do a really good job. They create a product and shop their work to publishers, but—as with music—very few “make it.” A few years ago, I met Detlef Schmidt, who is a Precision bass aficionado and has a passion for the early “cowboy plank” basses. At the time, he wanted to feature a 1951 that I co-own in his book, but I am very private about my stash, as is the instrument’s other owner.

At Arlington, Detlef presented me with a hardcover copy of his book, which I was flattered to receive. Fender Precision Basses: 1951-1954 is by far the best single-source knowledge base on this topic. The book is gorgeous. The research is dead-on accurate. The photography is perfect. This is a must-have from the knowledge perspective alone. One superb aspect of the book is that it’s written “registry” style. Detlef tracked down as many of these basses as possible, documented them, and presented the results in serial-number order. The way he captured this info is compelling, and he shows many typical modifications that occurred in the ’60s and ’70s. This is an excellent and honest presentation of all things original and modified relating to early-’50s P basses.

Learning is one of the great things in life, especially when it’s about a topic you love. All this new information came to me in a barrage that I could not wait to share, and I hope you enjoyed it.

In our next installment, I’ll discuss the influential changes I’ve seen from a vintage-bass viewpoint. With my 49th birthday past and my 50th on the horizon, my report will cover quite a stretch of time. A lot has come and gone during those years, so I hope you’ll check it out. See you then.

Kevin Borden has

been playing bass since

1975. He is the principal

and co-owner, with

“Dr.” Ben Sopranzetti, of

Kebo’s Bass Works (visit

them online at kebosbassworks.com). You can reach Kevin at

kebobass@yahoo.com. Feel free to call

him KeBo.

Kevin Borden has

been playing bass since

1975. He is the principal

and co-owner, with

“Dr.” Ben Sopranzetti, of

Kebo’s Bass Works (visit

them online at kebosbassworks.com). You can reach Kevin at

kebobass@yahoo.com. Feel free to call

him KeBo.

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Shop Scott's Rig

Shop Scott's Rig

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)