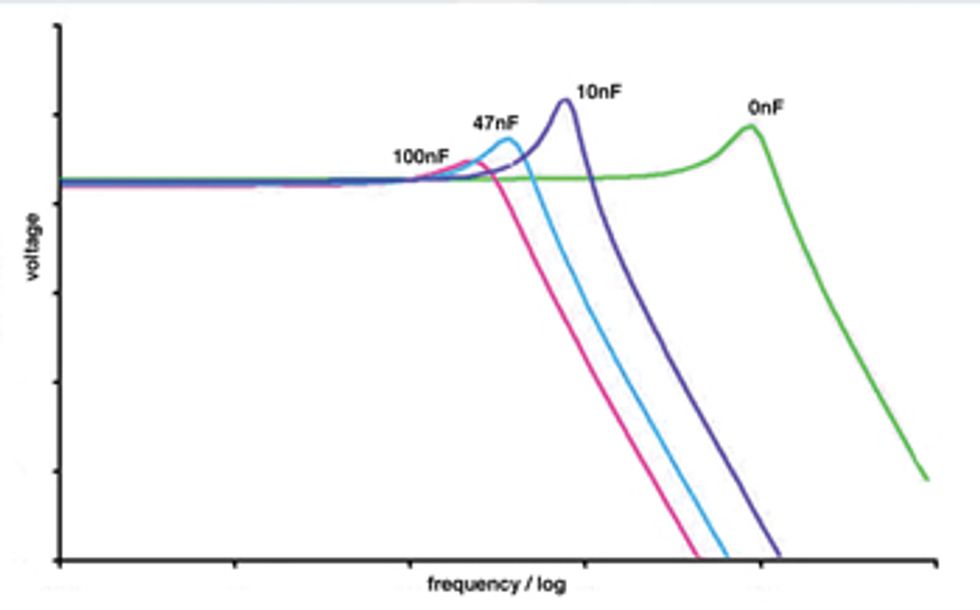

Different capacitors change the sound by lowering or raising the cut-off frequency. Moving to higher values lowers the cut-off frequency and vice versa.

In last month’s column [“Cheap and Easy Bass Mods,” May 2012], we began our bass-modding adventures by looking at ways to wire and configure passive pickups and potentiometers. Let’s stay with the “cheap and easy” theme this month and explore passive tone controls.

Most basses come with a treble roll-off knob. Essentially, its job is to reduce the highs in a full-range signal and simulate a dampened upright bass or darker flatwound sound. I’m not sure how many bassists actually use this control. Unlike guitar, treble isn’t the most important tonal range in a bass’ frequency spectrum, so perhaps these tone controls are on basses simply because guitars offer them and designers feel obliged to share the love.

That said, the standard tone knob resides on many basses. If this includes yours, you should either make good use of it or swap it for something better. (We’ll explore the latter in a future column.)

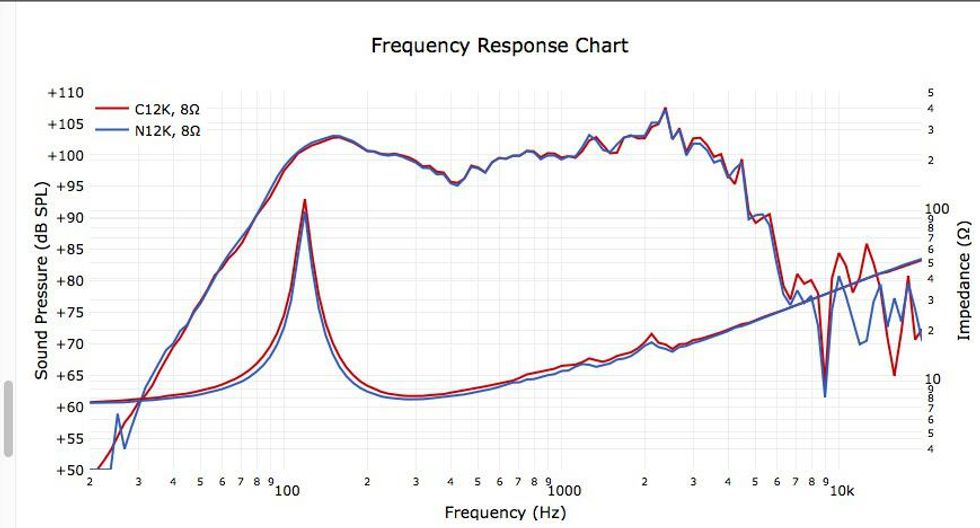

Meanwhile, let’s review the situation: Our signal chain starts with the pickups and their specific sonic signature. A pickup’s characteristic peak is its resonant frequency. When we use our tone controls, we essentially modify the size and position of this peak. As with all passive systems, a tone control can only reduce a part of the spectrum, but never add to it. Boosting a frequency is an exclusive feature of active electronics.

Unlike an active EQ—which can cut a specific frequency and even some surrounding ones—a passive tone control cuts only higher frequencies. The treble knob is a simple (or first degree) filter that’s formed by a resistor and a capacitor shunt to ground. Its cut-off frequency is mainly dictated by the capacitor’s value, at least for a given pickup and potentiometer combination.

A very common value is 47 nF. If you want to experiment with capacitor value, get a variety of different values (20 nF to 100 nF are usable values to start with) and test them out with your tone control. Moving to higher values lowers the cut-off frequency and vice versa.

Here’s a tip: Instead of soldering and unsoldering each capacitor to your potentiometer, solder two wires to the pot and then lead them outside the control cavity for easy access. You can then solder some clips to these wires or simply use bare wire to attach each capacitor. This trick allows you to easily audition the capacitors one after another.

You can see in the diagram how changing capacitor value is a pretty limited way to modify your bass guitar tone. Not that it doesn’t have much effect—it does—but we aren’t changing anything in the lower regions that characterize the bass spectrum.

The only way to do this and still stay passive is to use L-C filtering. An L-C filter is basically a network of capacitor, resistor, and inductor. Depending on the values and wiring, you can put a notch in your spectrum and vary its position, width, and depth. Instead of calculating the values and getting the parts on your own, I recommend looking for a commercial solution. Such L-C filters can come with a simple pot for a single frequency or rotary switches that directly dial in various presets.

One problem is that in a passive circuit, the parts interact with each other and it can get rather complicated to determine the sonic outcome. In practice, this means that an L-C filter’s tonal shaping will shift when you add in a second pickup. Though complex, the technical background is very interesting, and if you want to dig deeper, you can easily find more info on the web.

But does anyone use L-C filters? I’ve rarely had a bass with L-C-filtering on my workbench or seen it anywhere out in the wild. For me, L-C filtering is too variable and doesn’t provide enough visual information to be useful, especially onstage when you need to act fast.

The passive tone pot can tame an aggressive sound or let you quickly adjust to the sonic demands of different playing styles, and it’s always right at your fingertips. But other than that, you can do more effective sonic shaping by working with controls on your amp, tweaking your pickups, or using an active tone control.

Before you label me as someone who always cranks everything wide open, I’ll leave you with a short teaser for the next column: Where is your place in the mix and what strategy gets you there?

Heiko Hoepfinger is a German

physicist and long-time bassist, classical

guitarist, and motorcycle enthusiast. His

work on fuel cells for the European orbital

glider Hermes got him deeply into modern

materials and physical acoustics, and

led him to form BassLab (basslab.de)—a

manufacturer of monocoque guitars and basses. You can

reach him at

chefchen@basslab.de..

Heiko Hoepfinger is a German

physicist and long-time bassist, classical

guitarist, and motorcycle enthusiast. His

work on fuel cells for the European orbital

glider Hermes got him deeply into modern

materials and physical acoustics, and

led him to form BassLab (basslab.de)—a

manufacturer of monocoque guitars and basses. You can

reach him at

chefchen@basslab.de..