What were the most dangerous times for bassists, guitarists, and singers? Surely the '60s. Not because of wild backstage parties, drug abuse, or high-risk early international travel, but simply because of electrocution caused by amateurish electrical installations with missing grounds.

That's exactly what inspired Leo Fender to develop the TR-105, the first "Wireless Remote Unit," as they called it, back in 1961. Unlike the P-bass, this was really a world's first, but unfortunately a rather unsuccessful one. The unit was directed at guitarists, bassists, and accordionists, and had a radius of 50 feet—enough distance for those pre-arena stage dimensions. It looked surprisingly similar to modern units: a set-top box and a belt pack. Its transmitter, which weighed only 5 ounces, had an impressive frequency range of 20 Hz–75 kHz, while the receiver covered 20 Hz–20 kHz, with 100 to 150 hours of operation on one mercury battery. The system came with a hardcase, weighed 15 pounds, and cost $269.50—roughly $2,500 today. For whatever reason, it didn't catch on and Fender only offered it for around a year.

It wasn't until 1976 that Nasty Cordless, Inc. (later renamed Nady Systems) and Ken Schaeffer's Vega Diversity successfully entered a broader market. Both were analog devices and used a process called companding: a word-mix of compression at the sender side and expansion on the receiver side.

The specialty of the Vega was an integrated audio circuit that was known to colorize tone. This doesn't have to be a bad thing, as AC/DC's Angus Young is still using his today, even in the studio, and sees it as a central device for his signature sound. (See PG's AC/DC Rig Rundown from September 2016.) These systems also had greater operation ranges, so they were good for stadium stages.

Today, wireless technology is thriving in all aspects of electronic products, with cables nearly a thing of the past, except among—astonishingly—many musicians who still like to knot and tangle them.

Wireless systems got a bad reputation because of their early teething troubles, which included dropouts and problems picking up radio transmissions. Some guitarists really look down on them because of these initial foibles. Today's budget analog wireless systems can have companders with a fixed ratio, and this can make them sound unnatural. Better ones have more natural sounding companders that make it much harder to tell the difference between wired and wireless sounds. And the newer digital systems are even topping these, with their high-quality A/D converters.

In the foreground of today's discussions about wireless systems are most often things like tone, dynamics, range, energy consumption, bandwidth, and dropouts, while electrocution isn't that much of an issue. Although it should be for anyone touring exotic places with lesser-controlled electrical environments.

Today, wireless technology is thriving in all aspects of electronic products, with cables nearly a thing of the past, except among—astonishingly—many musicians who still like to knot and tangle them. As with all things mechanical, cable breakage isn't such a rarity and one might even be tempted to say that newer wireless devices excel in reliability. And—opposed to many early transmitters—they've switched to USB-equipped accumulators and far lower energy consumption. Choosing a system is almost a no-brainer, even though the sheer number of models is vast. With the exception of low-end budget models, almost all units fulfill the criteria of reliability, tone, ease of use, and operational range.

Fender was first in the wireless game with its unsuccessful TR-105 in 1961.

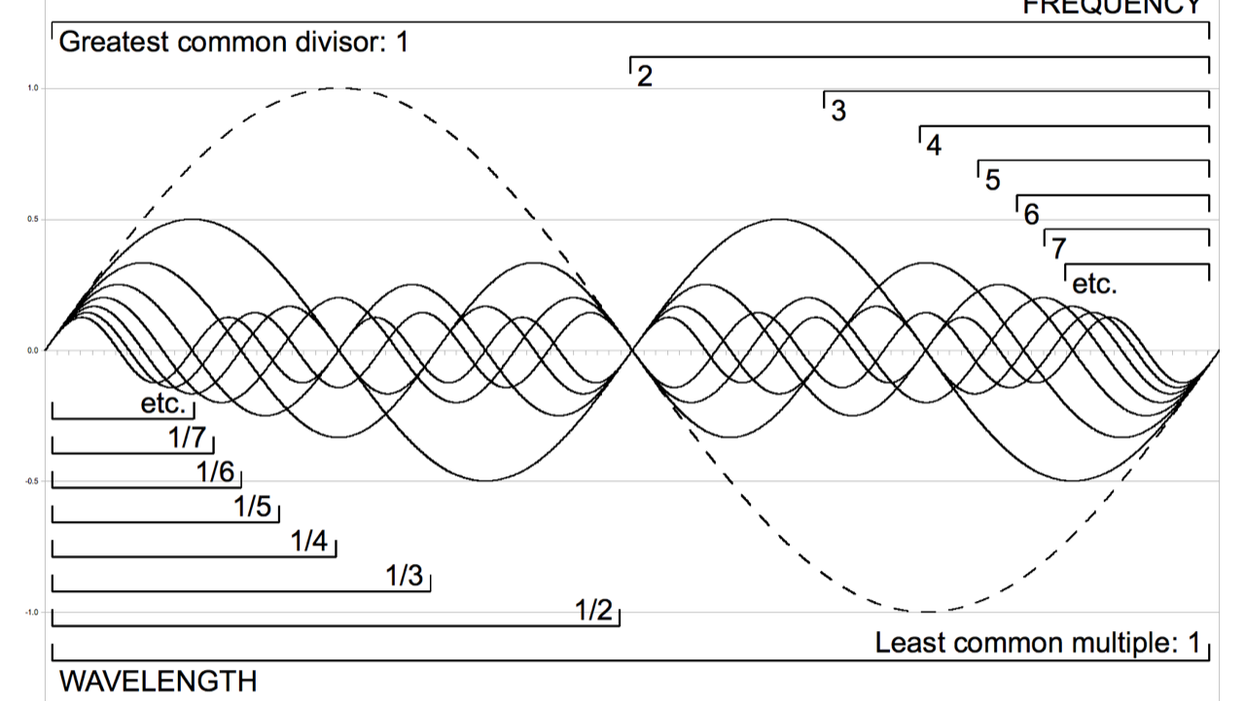

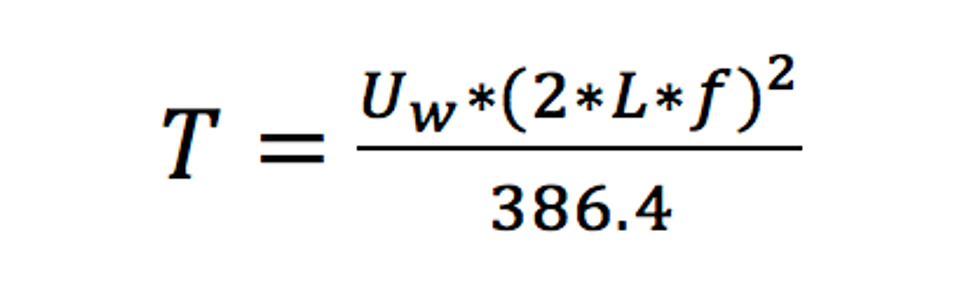

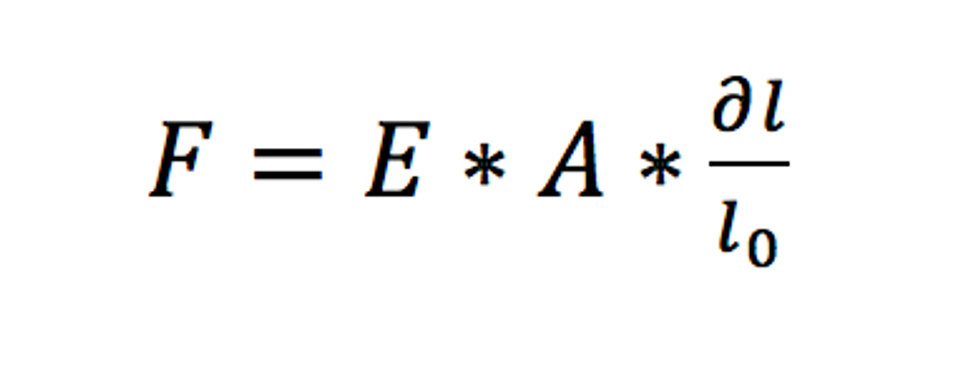

For us bassists, there are a few extra points to keep in mind. Our signal is pretty dynamic, so our wireless system should be as well. Analog wireless systems need to compress the dynamic range of the audio before it can be carried on a radio wave. Not only can this have an impact on tone; it also limits dynamics. Therefore, digital is the way to go, especially since these have a better low-end range.

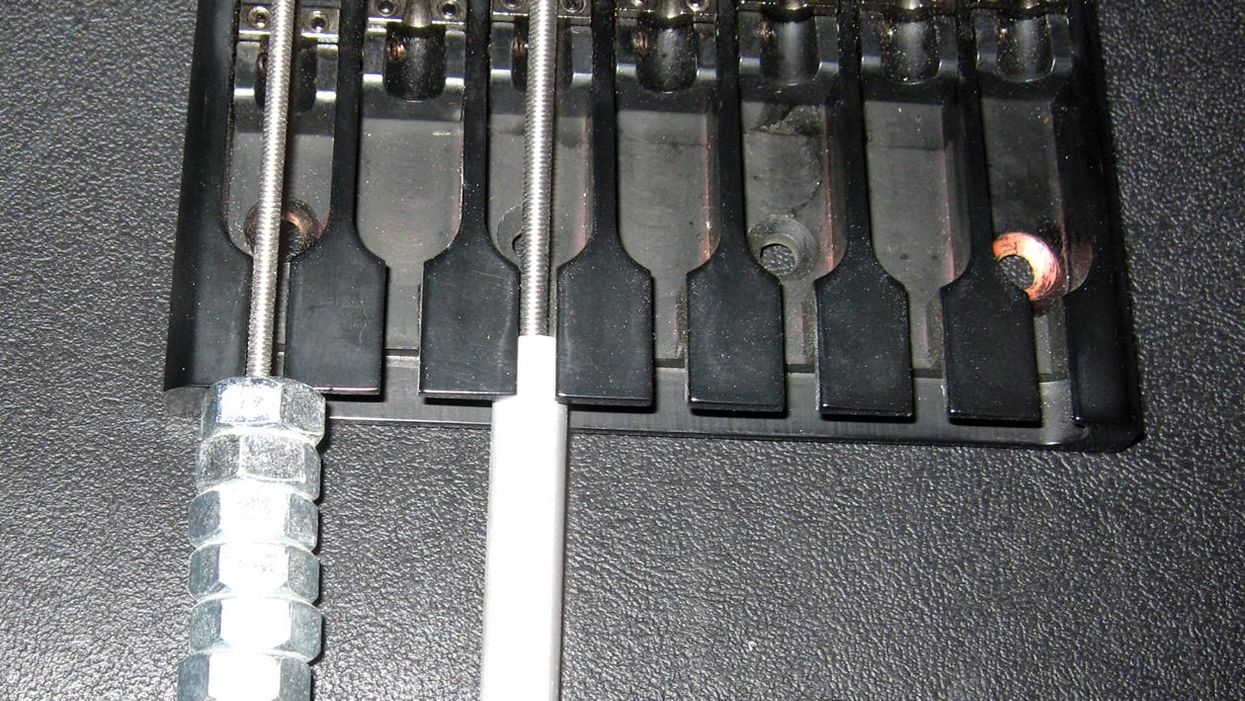

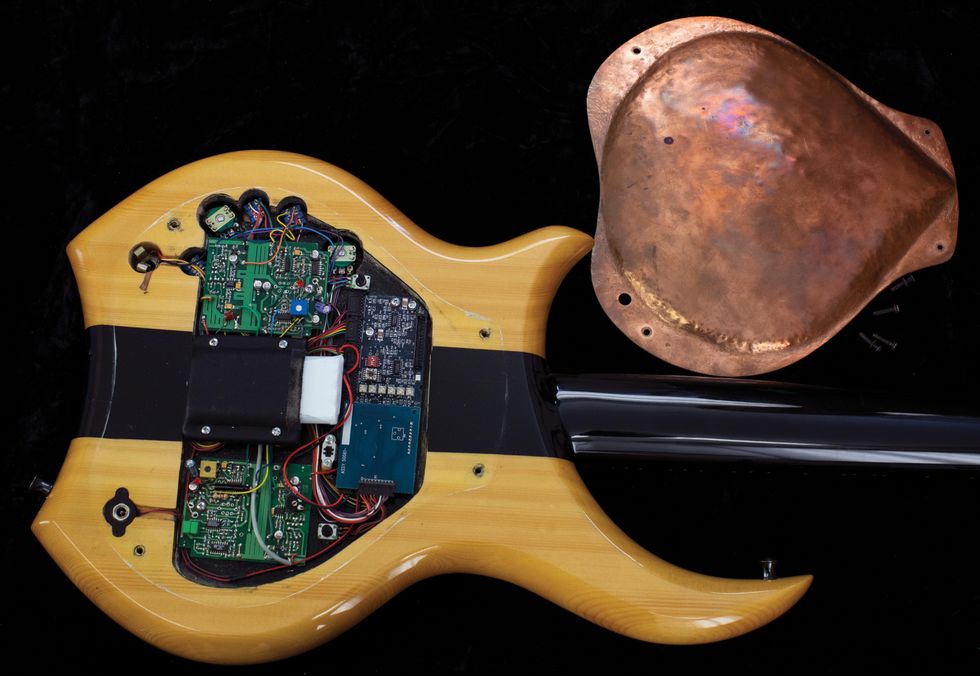

All those owning basses with active pickups or preamps should check compatibility before buying, plus keep a few other things in mind. It's sometimes not mentioned in a system's spec lists whether it will work with an active instrument's stereo output jacks, due to a TRS-related connection issue that can occur. Output levels of active pickups can be another issue, which is why many devices come with a gain-adjustment at the transmitter. And finally, there can be whining and noise caused by insufficient shielding of the preamp on your bass, once the transmitter is plugged in and close to the electronics housing. To solve that, just look for a cable-equipped belt pack to keep the receiver's antennas farther away from it.

Some other common features to look for are capacity-load cable simulations, which are more directed at guitarists, and durable metal body packs, for the touring artist. Multiple transmitter supports could be nice to have, but are not essential.

Some research will help you find the right system. Don't be afraid to cut the cable! You might enjoy your new freedom to roam the stage.