| The sound engineers at OEM Inc. have spent thousands of hours with the original masters of the most famous songs ever recorded. They use them to create products like Jammit, an iPhone app that allows you to remix and play along with those original tracks. There are many, many things to learn from those original tracks. Through a partnership with Gearhead Communications, OEM Inc. engineers are sharing their discoveries exclusively with Premier Guitar readers in what we like to call Secrets of the Masters |

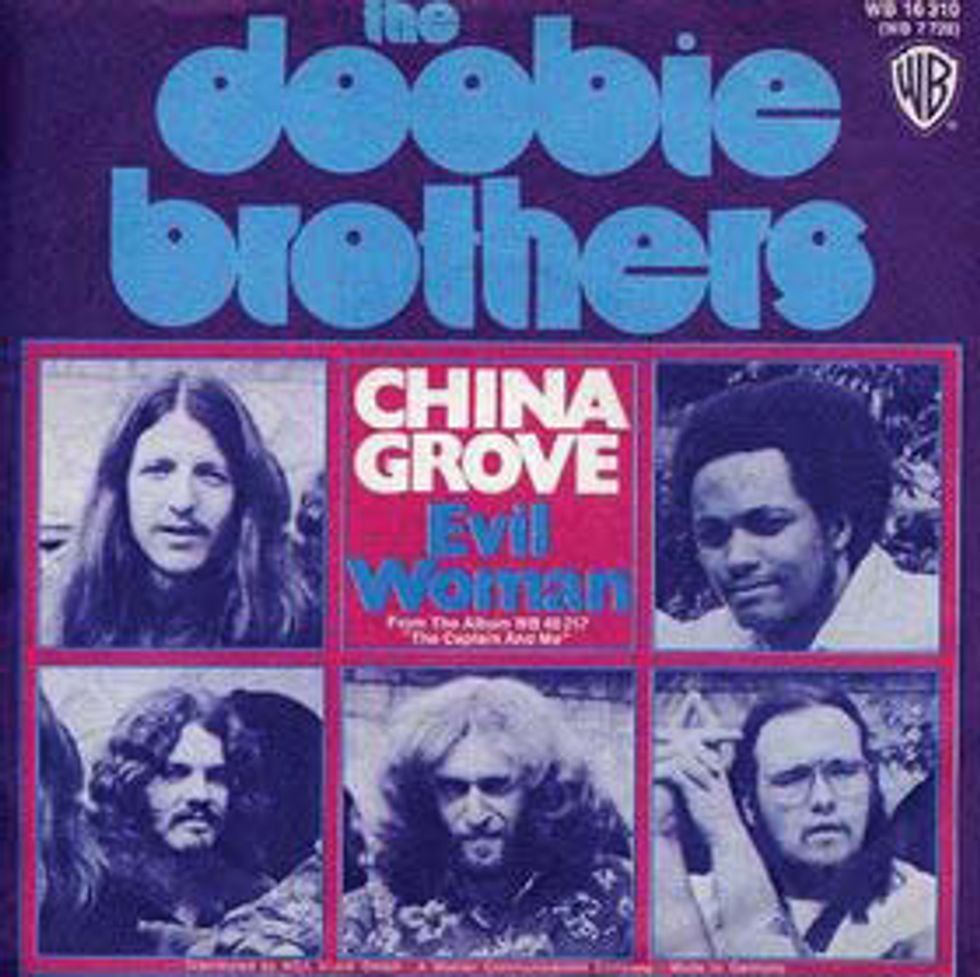

“China Grove” by The Doobie Brothers

“China Grove” by The Doobie Brothers

From the album The Captain and Me (1973 Warner Bros.)

Produced by: Ted Templeman

Engineered by: Donn Landee

Written by: Tom Johnston

Recorded at: Warner Bros. Recording Studios in North Hollywood, CA

Available in the JAMMIT “Classic Rock Vol.2” application

One of the many great things about ’70s music (besides all the artificial stimuli) is that most bands recorded a new album almost every year. This was the case for The Doobie Brothers when they returned to the studio shortly after the release of their 1972 album, Toulouse Street, to start production on their third studio album. After having success with Ted Templeman at the helm for their first two albums, The Doobies continued the proven formula for what was to become their most successful and recognizable album to date, The Captain and Me. Recorded in North Hollywood at their record label’s recording studio, the song “China Grove” would help propel The Captain and Me to double platinum sales status and become one of the band’s most loved singles.

I always love the opportunity to peek into the

recordings of some of my favorite engineers

and producers, and both Ted Templeman and

Donn Landee are near the top of my list when

it comes to albums from the `70s. From Van

Halen to Montrose, the simplicity and focus,

yet size and depth of their productions always

seems to catch my ear. Upon dissecting the

multi-tracks for “China Grove” I wasn’t all that

surprised to see (and hear) everything laid-out

and organized nicely, and immediately sounding familiar with the faders at zero and without

EQ or effects. I spent a few minutes listening

back to the album mix to get myself reacquainted with the overall vibe and sonic imprint

that I’d be trying to match for the Jammit version of the song. After several passes through

the timeless song, I dove in headfirst.

I always love the opportunity to peek into the

recordings of some of my favorite engineers

and producers, and both Ted Templeman and

Donn Landee are near the top of my list when

it comes to albums from the `70s. From Van

Halen to Montrose, the simplicity and focus,

yet size and depth of their productions always

seems to catch my ear. Upon dissecting the

multi-tracks for “China Grove” I wasn’t all that

surprised to see (and hear) everything laid-out

and organized nicely, and immediately sounding familiar with the faders at zero and without

EQ or effects. I spent a few minutes listening

back to the album mix to get myself reacquainted with the overall vibe and sonic imprint

that I’d be trying to match for the Jammit version of the song. After several passes through

the timeless song, I dove in headfirst. Tracks (in no specific order):

1) Bass Drum

2) Snare Drum

3) Drums

4) Hand Claps

5) Tambourine

6) Bass

7) Guitar Rhythm-Tom

8) Guitar Rhythm Overdub-Tom

9) Guitar Lead

10) Guitar Harmony

11) Piano Lo

12) Piano Hi

13) Lead Vocal

14) BG Vocals

15) BG Vocals Hi Harmony

16) BG Vocals Lo Harmony

At this point in recorded music history, most bands were still playing together while tracking in the studio as opposed to overdubbing almost all of the instrumental elements. It was evident right away that this was the case, as I could hear some guitar amp sound leaking into the drum tracks and some drum tracks leaking into the guitar track. The leakage was very slight, which most likely meant that the guitar amp was well isolated in another room or booth.

Drums Just Keep on Lookin’ to the Left

The drum recording appeared to be relatively simple with only three tracks—kick, snare and a mono drum track that could have been an overhead or room mic, or a combination of several microphones bounced down to a single mono track. The drums sounded great as is and didn’t need much more than a little high-frequency equalizing. The one anomaly about the drums was that they were panned slightly off center. Usually in rock music, the kick and snare are both straight up the middle, but this song had the kick in the center while the snare was slightly to the left and the drum track even more to the left. That’s a bit strange, but it sure created a nice pocket on the right side of the spectrum for the guitars and percussion.

The production on this song was pretty standard for a song of this time period. Aside from the drums, there were some additional percussion, tambourine, and handclap overdubs. The bass performance and sound on this song is top notch. It sounds to me like Tiran Porter played the melodic line using a pick and plugged direct into the board. Matching the sound was a cinch. The vocal tracks were also quite easy to mix, as they sounded darn good right off of the tape. A little reverb and slight EQ was all that was needed to get it sounding like the original.

Talkin’ ‘Bout Rhythm Groove

Other than the guitar solo and harmony overdubs, the guitar on this song is relatively straightforward, as well. From what the track- sheet read, the main rhythm guitar track was played by “Tom,” which I’m assuming was Tom Johnston, the band’s lead singer at the time and the writer of the song. An additional guitar overdub was added later to fill out the sound and thicken up the rhythm section. I spent a significant amount of time balancing and panning the rhythm guitars to get them to match the original album version, but couldn’t quite seem to nail it. I threw on some headphones to get a closer inspection of the original and noticed that the quarter-note delay that is on the main guitar track in the intro and re-intro is bypassed once the verse kicks in. This one subtle change allowed the rhythm guitars to sit properly in the mix.

I added a bit of reverb to both guitar tracks, but automated both the reverb level and the track volume of the cleaner guitar track in the bridge. Back in the day, this would have been done manually by whoever in the room could lend an extra hand to the mixing console. In 1973, fader automation on a recording console wasn’t a standard feature like it is today, so any volume, pan, or effects rides would have to be done in real-time as the mix was being laid down. This used to be part of the magic of mixing. It was a performance in and of itself. Today, one engineer can replay the mix over and over recording each and every push of a fader and turn of a knob until it’s just right before having to commit and print it as the master mix.

Mix Masters

In the days predating automation, it wasn’t uncommon to find the engineer, producer, band members, and sometimes even assistants performing these same moves all in one pass, like a well-rehearsed orchestra. If someone didn’t hit their cue, or adjusted the wrong knob, the whole mix would need to be done again from the beginning. Everything from grease pencil marks on knobs to razor blades taped above the faders (to block it from moving too far) helped make this cumbersome process a little easier. In many cases, the relative inaccuracies of this method produced some really magical results.

I have fun mixing just about every song we release for Jammit, but for some reason this one made me feel slightly nostalgic, even though I wasn’t even a glitter in my mother’s eye at the time it was made. It made me remember the stories I’ve heard many times over of how things used to be done when motorized faders on a console was as far-fetched as a little white box that can hold 10,000+ songs in your pocket. Having these limitations really put a premium on talent and ingenuity. Now I’m not going to go as far as to say that today’s music isn’t as good as it once was. (I wouldn’t want to sound too much like an old fogey, would I?) But it definitely makes me wonder if a lot of these songs that we call classics today would have been the same, worse, or better had the musicians, producers and engineers had all the tools and freedom from limitations that we seem to have today. I guess the only way we’d ever be able to find out is if we could take a nuclear-powered DeLorean back to 1973. Unlikely, just like the iPod 37 years ago.

To see/hear how you can play along to (with tab) and make new mixes of “China Grove” and other songs from the original multi-track masters, check out www.jammit.com.

Chris Baseford is a Canadian-born recording engineer/mixer/ producer who has worked with some of the top names in the rock music world. Having spent many years mixing on large format analog consoles, Chris has made the transition to mixing “in-the-box” and continues to push the boundaries of what is possible in the all-digital domain of music production.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)