Much has been written about how Fender and Marshall contributed to the early development of guitar amplification. As in every industry, there are pioneers and innovators who get the ball rolling, followed by inventors and entrepreneurs who seize on opportunities the originators may have overlooked. For instance, both Fender and Marshall were very late to the party on adopting increased gain and the master volume.

With the advent of the Marshall stack, guitarists experienced a major paradigm shift. Not only did this amp sound good and deliver on volume, it also offered an imposing visual announcement of intent. “We’re here to rock, so strap in and plug your ears!” In the beginning, this was more about coverage and clean power than circus theatrics. Onstage monitor systems were rudimentary at best, and sealed-back guitar cabs delivered beamy projection, which required several amps and cabs onstage to allow performers the freedom to move about. What started out as a matter of necessity ended up being an iconic statement of purpose.

Now, if you’ve ever played a full 100-watt stack—let alone two or three at once—you know you’re never going to need or even be able to use a fraction of that power, yet the mere presence of such an imposing backline was undeniable evidence that you meant business. And that leads to the long-held myth about big stacks—that they’re all dimed to the max and were the source of all the distortion. In fact, the opposite was true. The idea was maximum clean power and wide-area dispersion of sound.

Case in point: Pete Townshend decided early on that while Marshalls were certainly loud, there was something essential missing from the formula, thus setting the stage for his discovery of David Reeves and their mutual quest for the loudest, cleanest sound possible. While the dual 100-watt 4x12 stack remained the form factor of choice, Townshend’s quest led to the refinement of preamp tone and the ever-increasing power handling capacity of the speakers. Where the sealed-back Marshall cab made it possible to use lower-powered speakers, the original Sound City cabs, and later Hiwatt cabs, were vented in the back and loaded with progressively higher-powered cast-frame Fane speakers that featured high-temperature “glass fibre” voice-coil formers. A stiffer suspension allowed these speakers to withstand the punishing excursions that would easily destroy a typical Celestion of the period.

When Hendrix came to London, Townshend recommended he check out Sound City amps. Early on, Hendrix used both Marshall and Sound City, and there is plenty of archival evidence indicating this went on for about two years. Revisionist history now proposes that Hendrix used “the Marshall for distortion and the Sound City for clean.” While that may seem logical in hindsight, the facts suggest otherwise. It’s an accepted article of faith that most of the distortion in Hendrix’s live sound came courtesy of an Arbiter Fuzz Face, and between outbursts of sonic fury, his clean stage sound was gloriously deep and wide.

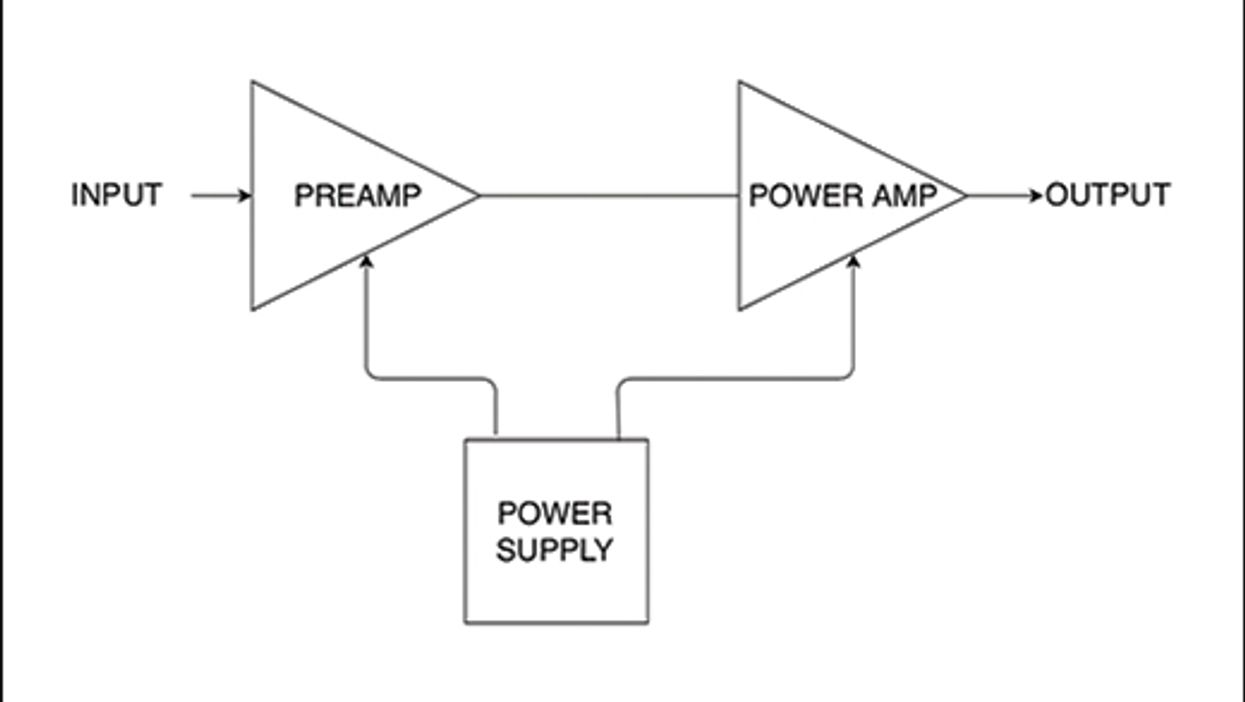

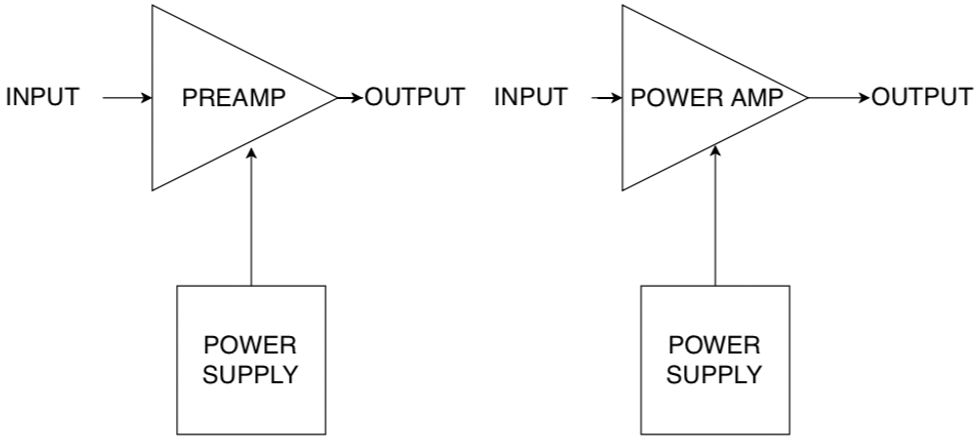

As bands became more popular, venue size increased, and the need to fill those venues with sound begat not only the need for more powerful and reliable guitar amplifiers, but also more powerful sound reinforcement systems to help singers and drummers keep up. And therein lies a tale of two competing philosophies of an otherwise similar engineering endgame: Power and reliability were the key imperatives for both guitar amps and sound systems, yet the latter needed to stay sonically pristine, while guitar amp designers had to embrace the expanding popularity of distortion and feedback.

With the current trend towards amps that provide a “clean platform” on which to sculpt unique and colorful soundscapes, it should be no surprise that this is really where it all started. What has changed is that sound systems have come a long way, baby. The live-sound engineer now has a lot of control over what the audience hears, as well as how much sound pressure level emanates directly from the stage.

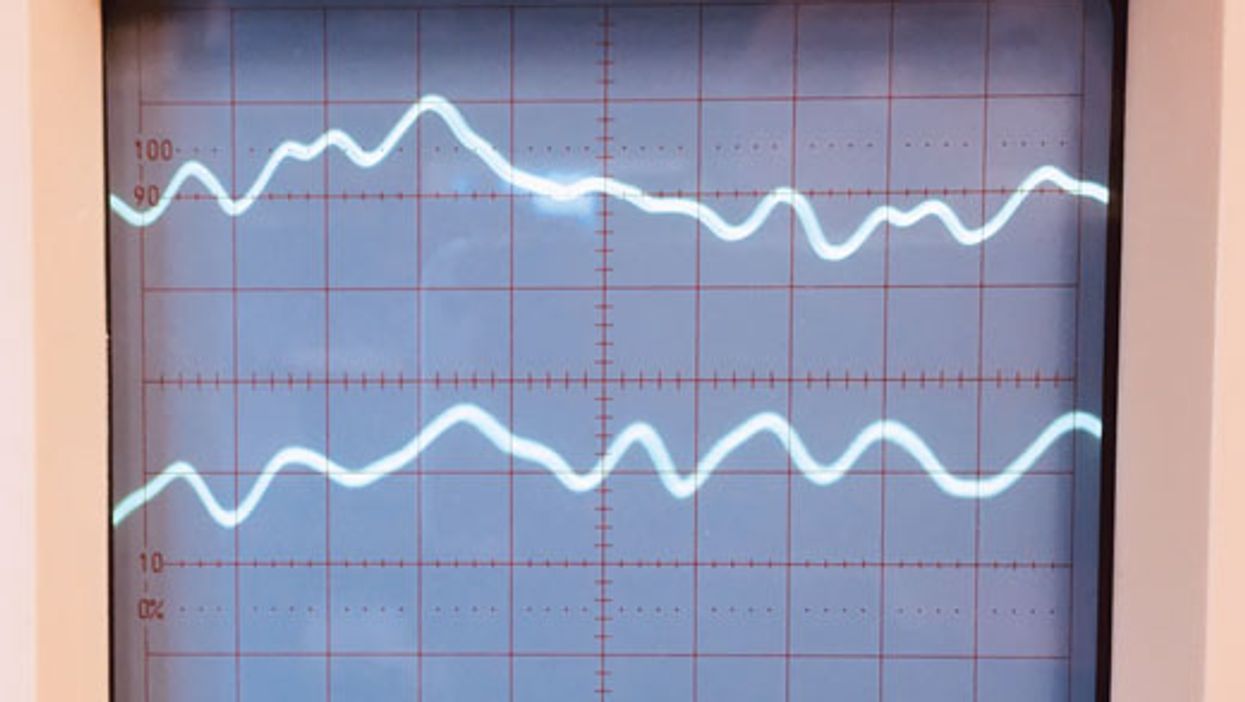

Today, the big amp revolution is over as a practical matter, but there’s good reason many of us are not so quick to ditch the big rigs. The sense of power and dynamics at our fingertips is as undeniable as waiting at a stoplight in a ’69 Charger with a 440 Hemi. It feels ready to rip at the slightest touch. This sensation has come to be known as “footprint,” and big iron is the only way to get it.