We’ve seen how string vibration is converted into the signal that’s sent to the guitar amplifier, and how that signal determines the response of a tube amp [“The Big Bang”]. Let’s now consider non-tube amplifiers, or what I refer to as “replacement technologies.”

When weighing the pros and cons of tube, solid-state, and modeling amps, it’s helpful to remember that tube amps came first. This means that pretty much the entire electric guitar vocabulary we build on today is informed by what the pioneers of electric guitar discovered about the behavior of tube amplifiers.

Now, imagine that solid-state amplifiers came first. It may seem like a preposterous exercise since the advent of the transistor sprang primarily from the need for improved efficiency, reliability, and conservation of space—all the things tube amplifiers weren’t good at. Yet, as a thought experiment, it’s safe to say that electric guitar music would certainly have evolved much differently had solid-state amps appeared first, and arguably not the way we recognize it today.

To sound palatable to guitarists, solid-state designs require some behavior management to minimize or eliminate the unpleasant and decidedly non-musical distortion solid-state amps can produce. In a modeling amp, most of the desirable characteristics of tube amplifiers are captured digitally, yet the modelers processing circuitry must not introduce any undesirable distortion, latency, or non-musical tonal artifacts. As important as they are to ongoing development, these methods of amplification are often trying just as hard to avoid what we don’t want as they are trying to produce what we do want. While the arrival of tube amplifiers represented a true paradigm shift from the acoustic to the amplified realm—thus opening new doors of expression for evolving players—solid-state and modeling amps simply prioritize functional evolution over inspirational involvement with the instrument.

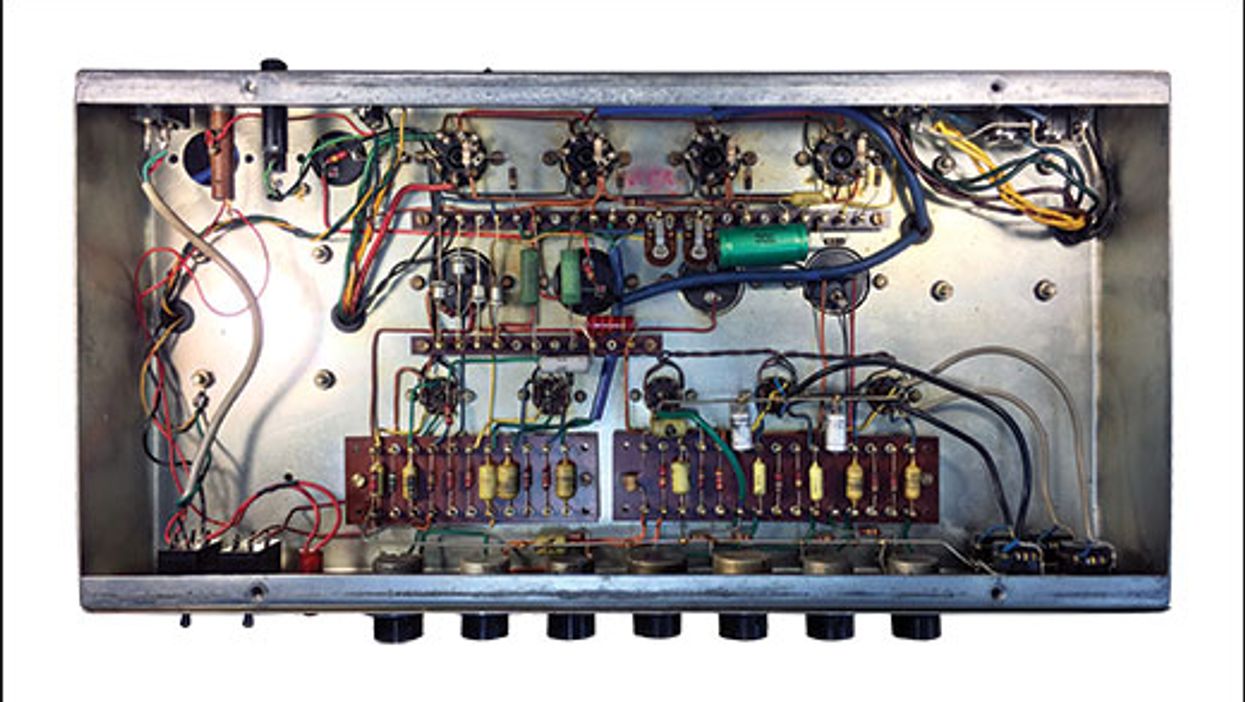

An iconic tube amp, by its very nature, is expected to be exactly what it is, and every yard-sale find potentially offers a new path to discovery. A tube amp becomes an indispensable extension of the instrument by virtue of its unique and sometimes irascible personality. No wonder players ultimately find their way back to tube gear.

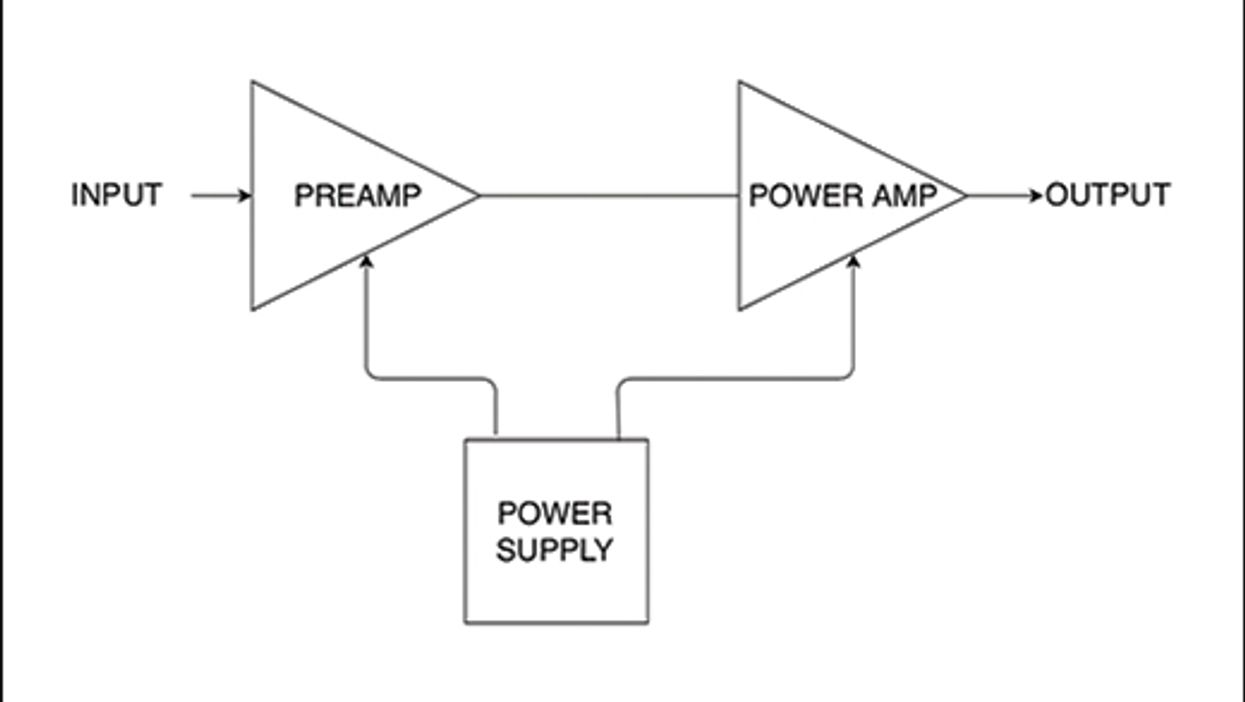

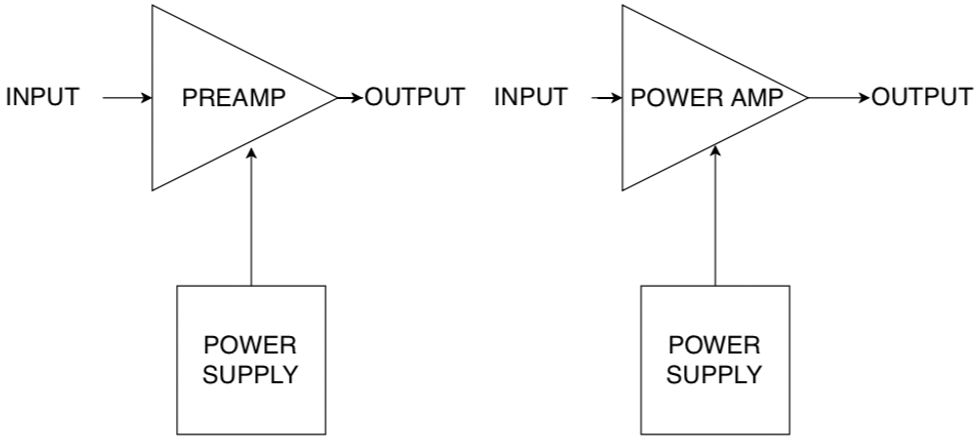

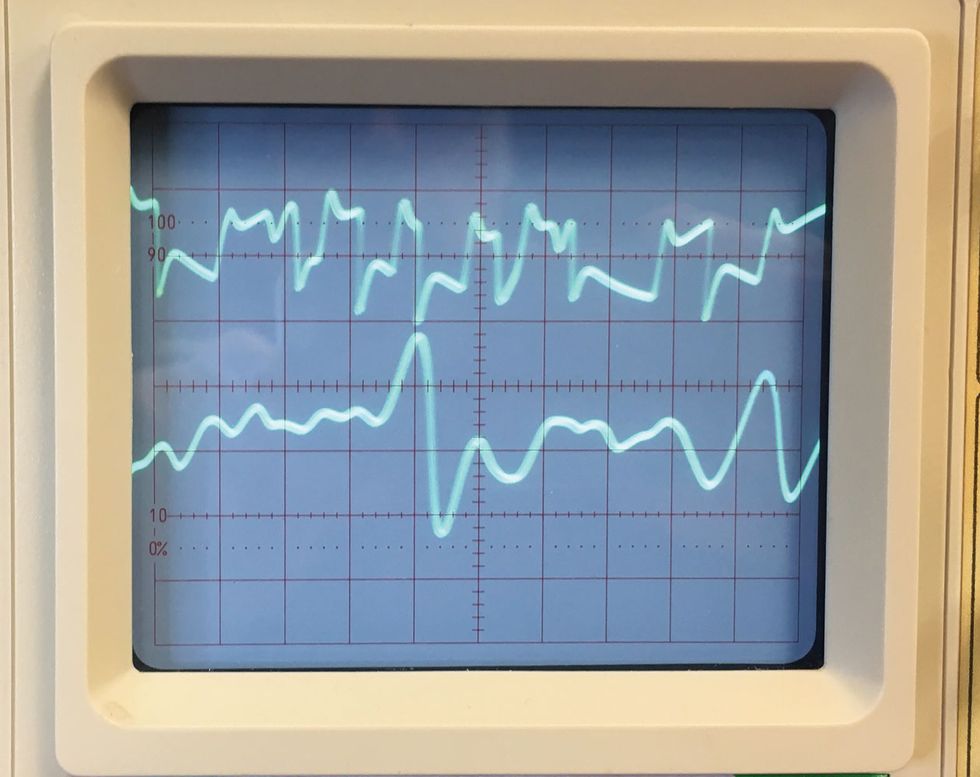

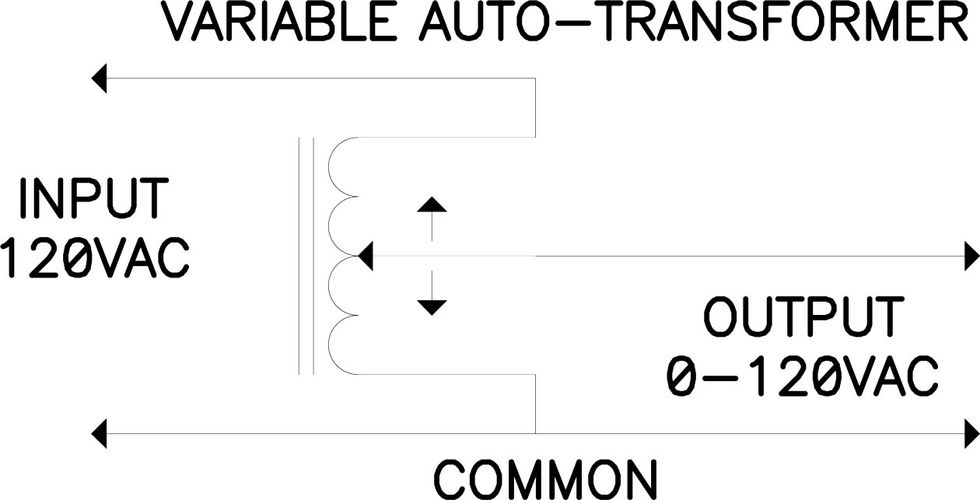

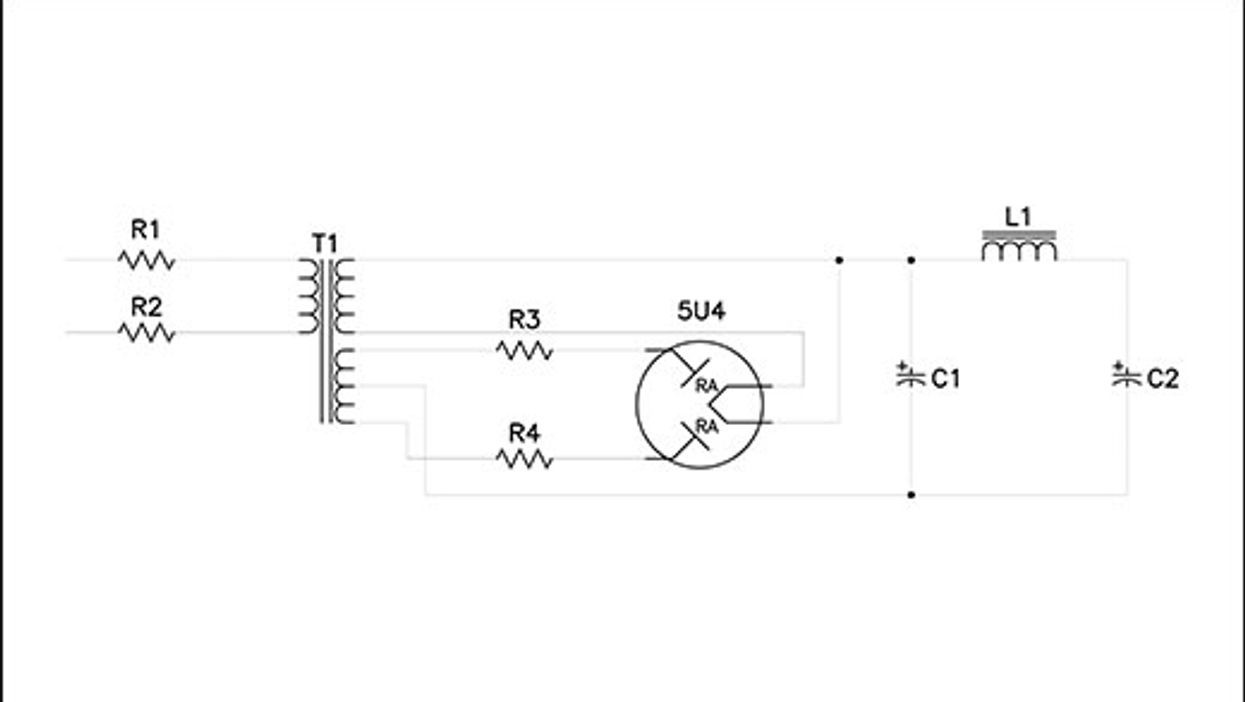

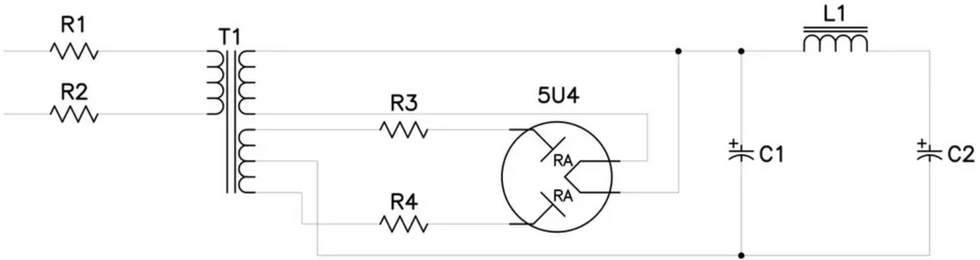

What happens in the front end (the preamp) of the amplifier is reproduced by the back end (the power amp) without necessarily influencing the latter’s performance. Preamp tube distortion as a general category includes light clipping, asymmetrical wave shape, and frequency modification, such as low-end and high-end roll-off. Power-amp distortion is highly dependent on circuit design: the amount of power this stage puts out, the type of tubes used, the construction of the power and output transformers, and, finally, how much its sound is influenced by the speaker it’s driving. Because this stage devours 90 percent of the current made available by the power supply, the power amp exerts great influence on the front end, which reacts to the ebb and flow of power-supply voltage at various playing volumes. This creates a feedback loop of sorts that causes a tug-of-war between the preamp and power amp, and is responsible for the sense of compression and touch sensitivity we experience. Only tube amps react this way in real time.

Speaking of feedback, many amps use what is known as local feedback to refine the sound of the power amp. A small amount of the output signal is fed back into the power amp input stage, which then controls whether the power amp will react more or less accurately to the input it receives. Because this feedback loop originates from the speaker output circuit, the amplifier also reacts to the speaker that it’s driving. Because different speakers have different electrical and mechanical characteristics, it’s no wonder that changing the speaker in a given amp not only changes the sound you hear from the amp, it also changes how the amp reacts to pick attack,which brings us back to square one—the Big Bang.

Picking a string sets off a chain reaction of both expected and unpredictable events that inspire the next pick attack. As a habitual string slammer who uses the blunt side of heavy Herco picks, I’ve developed a callous on the nail side of my index finger from scraping it against the strings. An evolving understanding of picking dynamics is driving me to modulate my former heavy-handed approach. Inspired by advanced pick-free explorers like David Torn and Jeff Beck, I’m slowly learning to back off and lighten my touch in an effort to develop a more nuanced, ethereal string timbre. I find the lighter my attack, the more harmonic control I have over amplifier distortion and dynamic range, and this yields an even greater appreciation for the multifaceted sonic bliss that is unique to tube amplifiers.