Chops: Intermediate

Theory: Intermediate

Lesson Overview:

• Understand how to separate

bass lines from the melody in

a fingerstyle arrangement.

• Learn the mystery of the

minor-third modulation.

• Decode the slippery

16th-note triplet.

Click here to download the sound clips and full score from this lesson.

I’m really excited to be a part of the PG stable and I’m also looking forward to sharing some ideas and thoughts I have about playing the guitar with each of you. Please feel free to write to me with any questions you may have—anything that may need clearing up, as well as ideas for future articles.

So now let’s get started with a piece I composed several years ago, “The Small Stuff.” Many folks have asked if I wrote this and “Things Are Looking Up” since my recovery from massive heart failure in March of 2011. Actually, I wrote both of these pieces many years ago.

“The Small Stuff ” contains several compositional elements that really make a solo guitar piece—a good groove, nice melody, and a solid bass line with clear separation from the melody. This separation of the bass lines and melodies is one of the defining aspects of my style. I really love to hear them both very distinctly and I spend a lot of time listening back to recordings before I release anything because it all has to work together and sound natural. Listen to the bass lines in tunes like Steely Dan’s “Josie,” the Jackson 5’s “I Want You Back,” or Stevie Wonder’s “I Wish.” These are excellent examples of what attracts me to music.

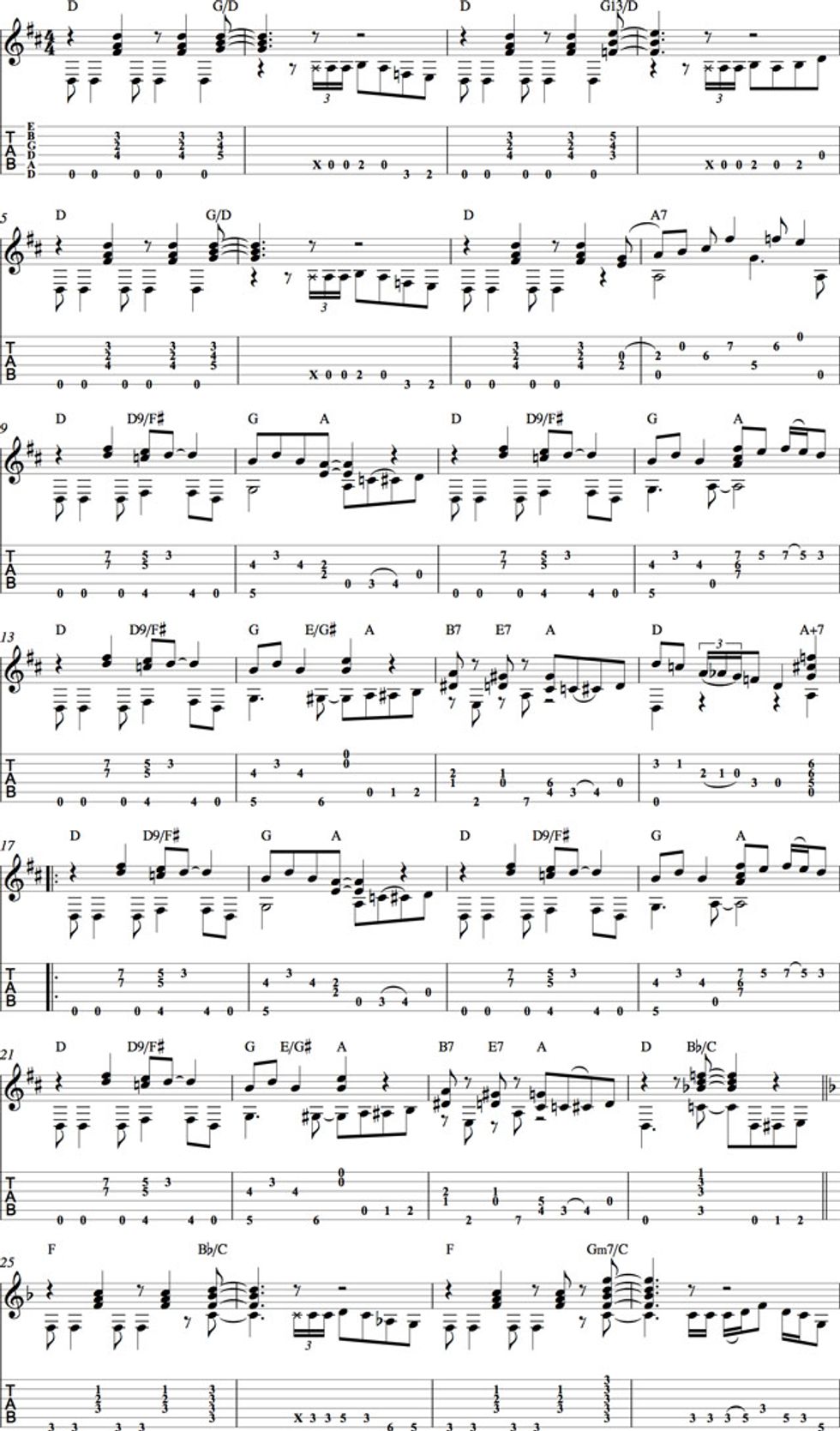

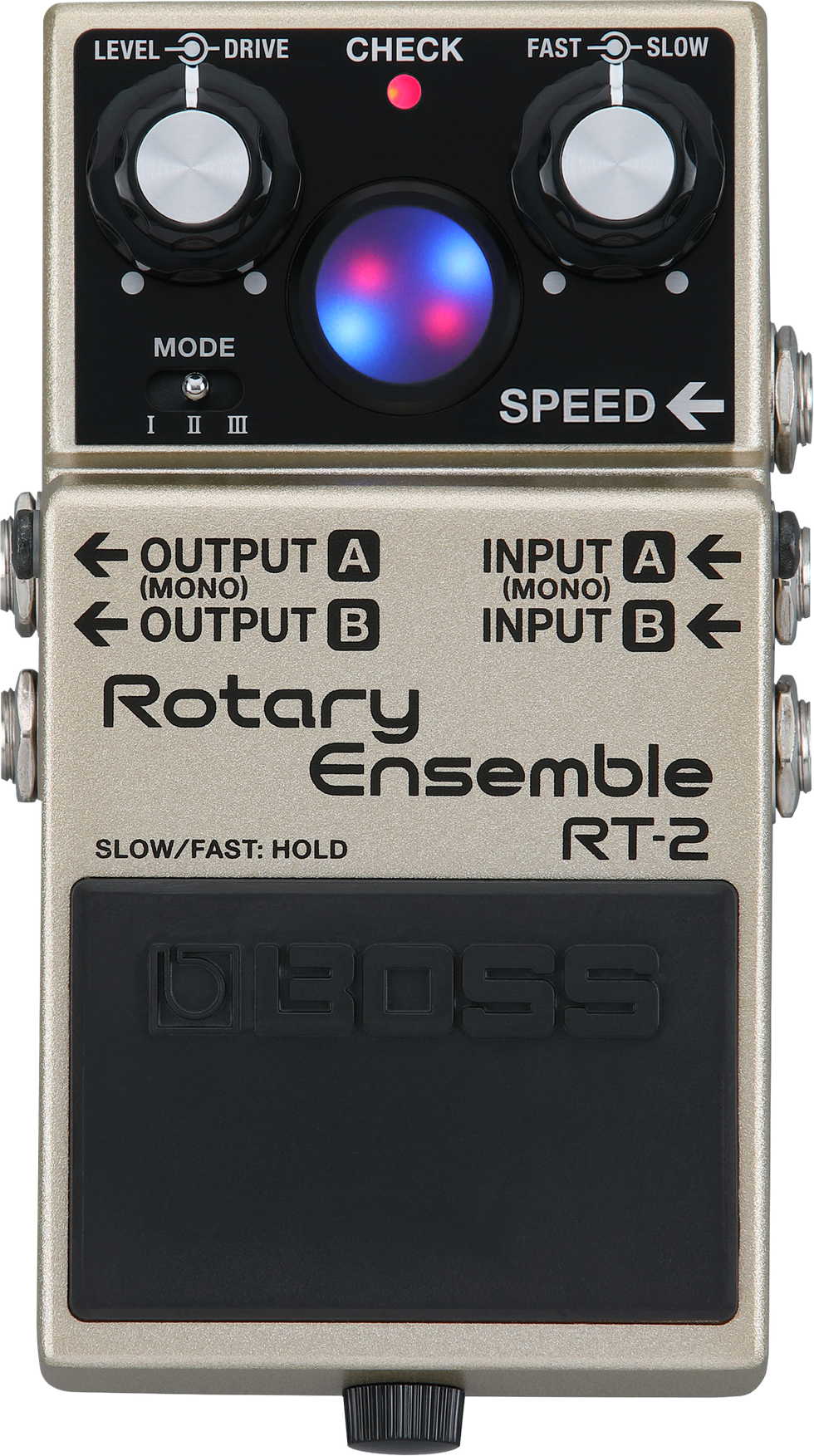

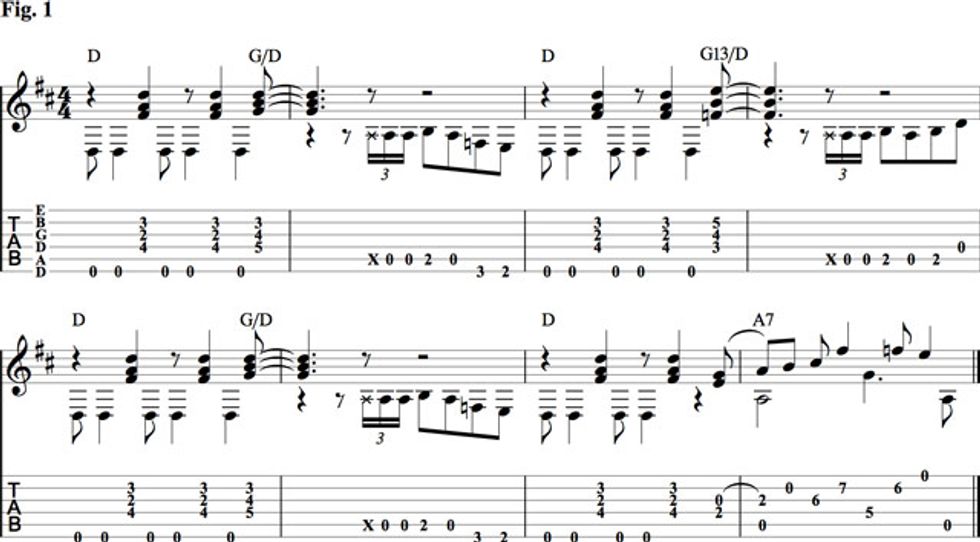

First things first. Let’s tune the 6th string down a whole-step to D—an octave below the 4th string. Now we’re ready. The intro, shown in Fig. 1, is fairly simple (relatively speaking, of course), but it’s a good way to get into separating the bass from the melody. Notice that the bass and the chords never strike at the same time. I really think of this as horns and bass, or keyboard and bass. (The parts actually transfer well to those instruments, if you’re inclined to give it a try.) This is a good technique for developing an uncluttered arrangement.

The first trick occurs in the second measure. The 16th-note triplet with the “ghost” note is hard to get in perfect time, so try playing the phrase very, very slowly. Think of your starting point (the and of beat 2) and the ending point (beat 3) and make sure those are lined up perfectly. Don’t forget to mute the 5th string with your lefthand index finger.

The next problem might be in the seventh measure leading into the eighth measure. The eighth-note on the and of beat 4 is a hammer-on from the open 3rd string to the 2nd fret. The bass note strikes on the downbeat of the next measure. So once again, you’ll need to isolate this part and practice it over and over until it feels natural. About 30 minutes ought to do it.

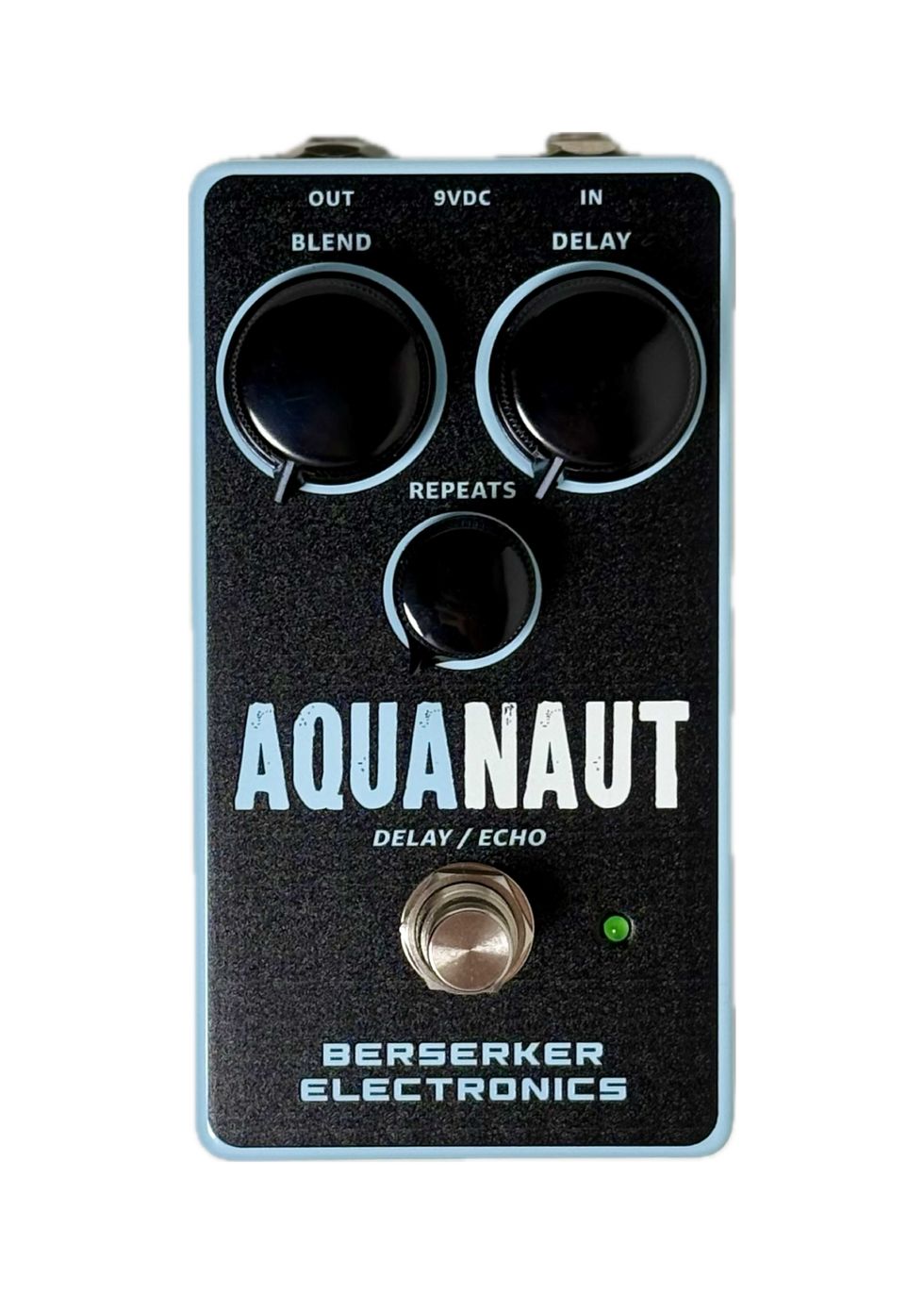

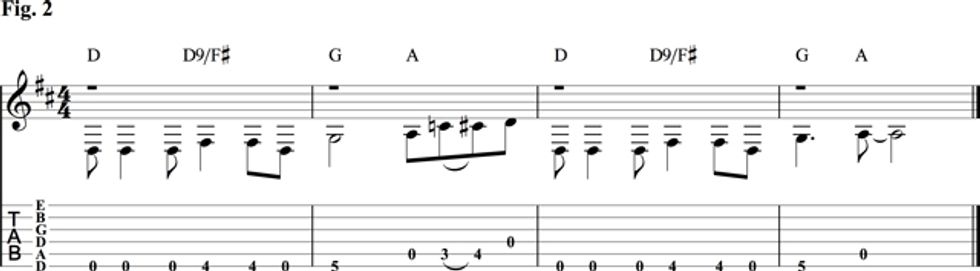

The main body of the tune begins at measure nine. Check out the bass line, shown in Fig. 2. Try playing each individual part along with the recording—bass line first, then the melody. Isolating each part and then slowly combining them is one of the best ways to solidify a tune in your head and see how each part fits together.

The real fun for me begins at measure 14, which you can see in Fig. 3. I absolutely love the way the parts work together here. And the A+7 on the last beat just kills me! Don’t be scared by the weird “+” symbol in this chord. We call this chord an augmented 7, which is just a basic dominant 7th chord with a #5. If it weren’t on the last beat of the measure I’d hold it out for another couple of beats— just because.

My favorite type of modulation, or key change, is moving up a minor third. I’ve done it in a few of my tunes and I think I picked it up from some of Larry Carlton’s early albums. In measure 24, I set up the key change with a Bb/C chord before walking up chromatically into the new key. I set up the new section with a short fourmeasure part, which emulates the intro just a little. You’ll notice that nasty 16th-note triplet shows up again, but because you have already worked that out, it’s not going to be a problem. The end of measure 32 begins another cool interplay between the bass and the melody, which you can see in Fig. 4. We start with a typical F chord before the melody moves chromatically into an interesting turnaround that goes between C7–Db9–C9–C7. This little half-step shake is common in jazz tunes and the syncopated rhythm between the bass and chords keeps things interesting.

At the end of the F section, I use D as a common tone to go from the B% to A7sus4 chord and ultimately back to the key of D. Then we have a repeat of the first part of the tune and it all ends on a big fat D9#11.

TIP: If you’ve got an old resonator guitar, try this tune on it. The music takes on a whole different personality ... kind of like Mississippi Delta pop. Tune in next time when we ask the perennial question: How many licks does it take to get to the center of a Tootsie Roll Tootsie Pop?