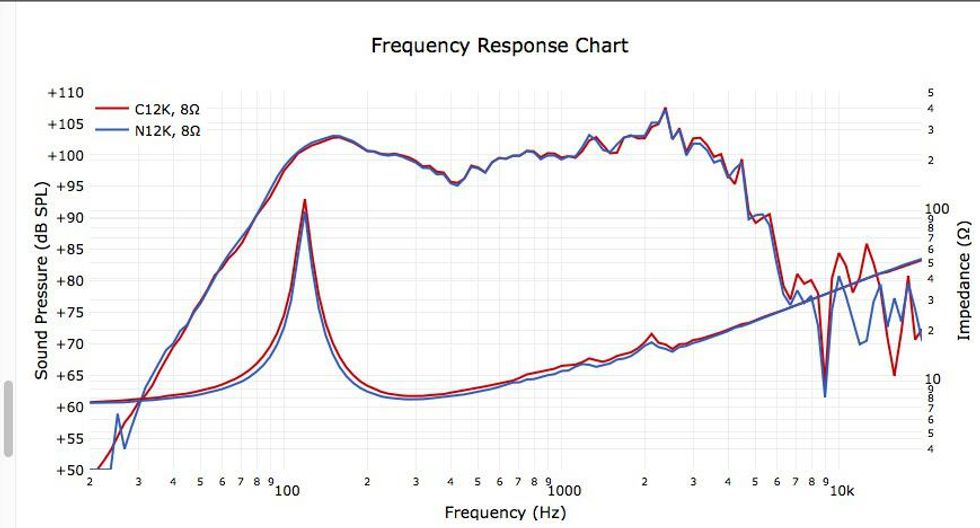

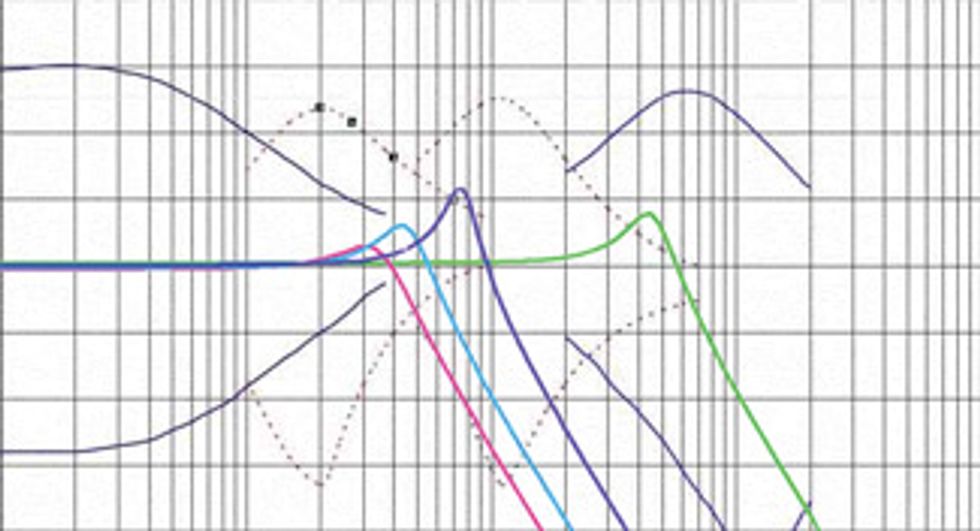

Fig. 1 Comparing passive highfrequency roll-off (indicated by the colored resonance peaks) with the cut-and-boost fl exibility of an active 4-band EQ (black)

Last month, we learned how passive tone controls offer limited possibilities for altering a bass guitar’s sound [“PassiveTone Controls,” June 2012]. This raises a question: To gain more control over our sound, should we turn to onboard active electronics or simply rely on our amps to do the job instead?

In the ’80s, active tone controls became widely popular among bass players—particularly those who came up in the ’70s, when the bass began to take a more prominent role in popular music. (Interestingly, guitarists didn’t embrace active electronics with as much enthusiasm during this time.) As with all fashions, the trend to “go active” later went back to passive, and now bass design swings back and forth between these two camps.

Forums are filled with flame wars between proponents of each approach. Some in the pro-active camp paint the passive bassist as a nature boy gripping an oiled-finished, natural-wood bass. Not to be outdone, many pro-passive players characterize active bassists as nerdy knob-addicts whose technical interests keep them from practicing. Let’s see if we can cut through some of the noise and look at the facts.

Fundamentally, a passive system is one that doesn’t require any additional electric power. The components are passive parts like resistors and capacitors. By contrast, active components are transistors, op amps, or other integrated circuitry—all of which require external power to operate. While passive tone controls can only cut a specific frequency (and this is typically limited to high-frequency roll-off ), an active tone control can cut and boost several frequencies at a time. This is determined by the number of frequency bands in a given system. The most common are 2- or 3-band systems with controls for bass, treble, and usually mids.

More elaborate active systems offer low- and high-mid controls or even parametric EQ, where you can sweep through a wider frequency range. Fig. 1 shows a frequency chart with a 4-band active EQ superimposed on the passive curves we looked at last month. Admittedly, this is just a rough overlay and the comparison is a bit unfair, but hopefully, you get the idea of the extended possibilities provided by an active EQ system.

The main argument for having an active system is tonal flexibility, but there’s another benefit: Passive circuits possess a high impedance, which basically means that any load (like a cable) you put after them alters the tone. This weakens the signal and sucks up the treble and even some midrange. Also, plugging a high-impedance device into an amp’s mismatched input just makes your bass sound bad.

Active circuits have a buffer that lowers the output impedance and essentially isolates the system from such loading effects. In practice, this means that you can use long cables or pass your signal through several pedals without losing much of the original signal. And plugging an active circuit into a mismatched amp input doesn’t have much influence on the signal. With an active circuit, the signal usually sounds and feels stronger, cleaner, and more detailed.

Given these properties, shouldn’t everybody have active EQ in their instruments?

Yes, because buffering and tonal flexibility can be a huge advantage. Imagine being able to play in different venues through different amps, yet your familiar tone is always right at your fingertips—and there’s no extra luggage to carry around. It’s pure comfort. And when you need to cut through the band or mix, you always have the ability to boost the midrange just a bit.

No, because you love your sweet, passive tone and nothing is missing. You hate to deal with batteries. You always use the same amp or outboard preamp and your rig offers plenty of EQ and tone-sculpting options. You like to keep all the electronics outside your instrument because that makes it easy to experiment with your sound and make changes in your signal path.

Once again, we realize the ultimate answer doesn’t exist! I see active preamps as an affordable luxury. First of all, don’t even think about putting an active circuit into a bad-sounding passive bass. Active electronics are designed for flexibility, not sound repair. If your bass is sounding too thin or weak, take a closer look at your amp and instrument. Active circuits are often called preamps, but real amplification is not their job. As with everything in your signal chain, the weakest part ruins it all. The advertising always claims product X is the most dynamic, flexible, power-saving, and quiet unit available. Learn to interpret the numbers and stay skeptical.

Because active circuits use batteries, make replacing them easier by having a quick-swap housing that requires no extra tools. Also, shop for circuits that indicate a low-battery condition hours before the cell actually dies. And remember, a true-bypass switch that lets you go passive is a musthave. If your favorite circuit doesn’t come with this, any simple 2-way (DTDP) switch does the job.

Ultimately, the passive-versus-active discussion comes down to this: You must start with a good passive tone. Depending on your needs, you either end there or go beyond by enhancing the passive tone with an active circuit. But remember, you don’t need active pickups in an active tone system. Active pickups have an internal buffer or preamp, and this gives them a low-impedance output —which may be just what you want. But you can combine any active and passive pickup or circuit, and we’ll explore this when we focus on pickups.

Heiko Hoepfinger is a German

physicist and long-time bassist, classical

guitarist, and motorcycle enthusiast. His

work on fuel cells for the European orbital

glider Hermes got him deeply into modern

materials and physical acoustics, and

led him to form BassLab (basslab.de)—a

manufacturer of monocoque guitars and basses. You can

reach him at

chefchen@basslab.de..

Heiko Hoepfinger is a German

physicist and long-time bassist, classical

guitarist, and motorcycle enthusiast. His

work on fuel cells for the European orbital

glider Hermes got him deeply into modern

materials and physical acoustics, and

led him to form BassLab (basslab.de)—a

manufacturer of monocoque guitars and basses. You can

reach him at

chefchen@basslab.de..