BilT Guitars happily shared its onboard-effects expertise with us, but they are unable to offer one-on-one advice. Please respect their time, and if you have questions about your own project, consult a local tech with the necessary skills outlined in the Q&A portion of this article.

In 2008 Brandon Darner couldn’t have known the mods he commissioned for his new Fender Telecaster Deluxe would spur the formation of one of the Midwest’s hottest new guitar companies. Just as he probably never imagined his Des Moines-based band, the Envy Corps, would later get a delicious sammich named in its honor at the local Zombie Burger + Drink Lab, a joint whose unique culinary tributes to classic undead flicks have been featured on several television shows. Both unforeseen consequences testify to the power of being a bit twisted in a place that’s really not known for that.

Just what were these mods—and who did Darner trust to carve up his guitar? He wanted a Sustainiac neck pickup, and two pedals—a Red Witch Fuzz God II and an MXR Carbon Copy delay—installed in his Tele. Tim Thelen, who’d already made a go of it as a luthier of boutique Strat-, Tele-, and Les Paul-style guitars, was the chosen luthier. (The burger? A grade-A ground-beef patty with pulled pork, ham, pepper jack cheese, salsa, fried jalapeños, red onion, and chipotle mayo.)

“I’d been going to Tim’s repair shop for several years at that point,” says Darner, who’s produced albums for Imagine Dragons, Radio Moscow, and more. “The Tele started off as just an average Deluxe. I bought it from Pro Music in Des Moines and took it straight over to Tim to paint it.” Darner broke two tuners throwing the guitar at its first U.K. gig, so it was out of commission for the rest of the 40-date tour. During the interim, his younger brother’s old Electra Modular Powered Circuits (MPC) guitar gave him the idea of installing effects in the Tele.

—Tim Thelen

Thelen was initially skeptical. “It took him a couple months of trying to convince me, but he was persistent,” he recalls. The Tele—since dubbed “the Monster”—has big routed-out cavities where the original Red Witch and MXR circuit boards and controls were dropped in before being covered by two custom pickguards. It also has a Jazzmaster vibrato and Mastery bridge. “It was pretty basic, pretty rough,” says Thelen. “It was super glitchy with the sustainer and all the stuff going on with those three effects—the Fuzz God is just insanity. But I got all the bugs worked out, and it was really pretty cool.”

Darner thought it was more than “pretty cool.” He insisted Thelen build more guitars with built-in effects.

The builder laughs as he remembers Darner’s optimistic prediction that people would “really want them.” “I was, like, ‘Well, no—nobody really wants this.’” But a few domino crashes later, BilT Guitars was born as a partnership between Thelen, longtime repair cohort Bill Henss, and Darner. Today, players such as Nels Cline, Mastodon’s Brent Hinds, the Melvins’ Buzz Osborne, Limp Bizkit’s Wes Borland, Imagine Dragons’ Wayne Sermon, and the Killers’ Dave Keuning use the BilT Relevator—the production model that evolved from Darner’s outlandish request. Here we talk to Thelen about the metamorphosis from one-off Tele bastard to offset mayhem machine.

Why you were initially reluctant to take on Brandon’s Tele project?

Well, you’ve seen what’s available with effects built in. It’s that cheapie Danelectro [the 2001 Danoblaster Innuendo and Hearsay guitars and Rumor bass], or the Electra with the cartridges. There isn’t a big, reputable gallery of popular—or even usable—instruments with effects built into them. The other side of the coin was that I had resigned myself to repairs. I was no longer interested in building guitars. I’d tried a lot of different things a lot of different ways, and I just kind of gave up. I realized the world didn’t need another Tele, Strat, Les Paul, or dreadnought copy. Then this came along, and it was pretty cool. It got a lot of attention locally.

Brandon Darner's guinea pig T-style.

What were the biggest surprises of that first project?

When we took the pedals apart, I was nervous that I was going to ruin this stuff. So I mapped everything out, hand-drawing schematics of the controls and how everything related on the circuit board.I came at it from the point of, “This is going to be kind of weird and dumb, so I’ve got to be able to put everything back in the pedal.” And the Sustainiac has its own quirks and weirdness as far as proximity and how glitchy it can be with crosstalking, the wiring, the circuit board. That was probably the second or third one I had ever installed, so I knew a little bit about it. But man, you start introducing all this extra stuff and you realize, “Oh, wow, if I touch this wire, it gets crazy. Shield that one, and all of a sudden every wire in the guitar is shielded.” It was extremely frustrating, standing at a bench all day chasing weird little noises.

So what happened after that Tele project?

We hired a couple of guys to help with the guitar side of things. One of them turned out to be Bill Henss. As he and I went along, we ended up collaborating on a guitar [a rosewood Jazzmaster-style model] for a client I’d had as a friend since the ’90s: Nels Cline. We approached him about making the Jazzmaster and he thought it was a great idea. So we had this distinct customer telling us this thing could really work. It’s not going to burn the world down, but there are people out there who would dig it. Then I stumbled across a picture of a Fender Marauder that I think is currently in Dave Rogers’ collection [at Dave’s Guitar Shop in La Crosse, Wisconsin].

We did a video tour of Dave’s shop a couple of years ago, and at the end we show that same Marauder.

Fender prototyped, like, eight of them and [the model] made it into the ’66 color catalog but was never produced. The one at Dave’s has three enormous plates, a ton of switches, a really cool offset body shape, a tremolo, the Starcaster headstock. The thing offered us something that wasn’t going to be in direct competition with Fender. It had everything, but especially the right amount of real estate on those plates for effects controls. I saw that and it just gelled. We studied the Marauder and ended up prototyping our first Relevator. That became our flagship—the only model we were offering. We started by doing a run of 10.

Relevator prototype.

What were the trickiest parts of getting the Relevator on its feet?

We’ve gone through different phases for how we power the effects. We initially used batteries, but we soon we realized that wasn’t an option, considering how quickly the delay eats batteries. We decided to build our own power supply, and we had a guy design a circuit for us. The thing was bulletproof, but it was ginormous. Today, instead of building our own power supplies, we provide a box that you plug a 1 Spot into, and then you go mono cable to the amp and tip-ring-sleeve (TRS) stereo cable to the guitar. You can switch the power on and off as needed.

Did those old Electra and Danelectro guitars teach you how not to do anything?

Mostly we were interested in how they did the surface controls. The overriding part was, “Okay, these are going to be awesome to have at your fingertips—you won’t be bent over anymore.” The two effects that dudes were bending over to play around with were of course delay—to make everything go crazy when you mess with the rate and repeats—and fuzz, or some way to make something oscillate. We’re not trying to take away a pedalboard. We’re not trying to eliminate stuff. We’re trying to add.

Tell us a little more about the Relevator’s fuzz circuit.

It’s along the same lines as a ZVEX Fuzz Factory, but so is every other fuzz. We played around with the ZVEX, but we didn’t copy the schematic exactly. We added our own components. We put a tone adjustment on there, a voltage sag, and a bunch of other stuff.

Is that how you do it with most effects? Unless someone says they want an exact pedal in the guitar, you make your own circuits?

No. We take the pedal apart and we put the actual circuit board in the guitar.For the delay, we buy a Carbon Copy and take it apart. For the fuzz—since it’s just a simple circuit—we had our boards printed for that. We populate them ourselves.

So you aren’t moving components to new boards that fit the cavity better?

No. It’s the same circuit board. We cut off the potentiometers and LED lamps, pull off the footswitch, and then re-route the connectors to the face of the guitar. We either buy the effect, or you send it to us. That’s why I talked about mapping it out. You take the pedal and draw a picture of what it is. You have to consider what’s upside down, what’s right-side up, how the potentiometer will be when this thing is mounted on the back of the guitar and the knob is on the surface—that kind of thing. You need a reference point before you start removing components.

Do you have to worry about proximity to other components or do special shielding?

Yeah. Those are things you sometimes only find out after everything is back together, and you have a weird whistle or hum or something. The effect controls are coming out of an enclosed metal box, so we try to recreate that as much as possible with shielding paint and shielding on cavity covers, but there are limitations. We end up having to use shielded wire for many connections. The delay is one of the worst—it’s a big-time crosstalker. I had to source very specific wire to get all the components right. Ground loops can make people insane. You get weirdness going on, especially if you’re playing at high volume.

Other than not having to bend down to mess with knobs, what are the advantages of having effects in your guitar?

If you’re going to manipulate a pedal, you’re going to have a lot better muscle memory with your hand and fingers than the side of your foot on a knob. We will not put an effect into a guitar if it’s just an effect that you set and turn on and off, like a distortion or boost. It has to take away something that’s kind of a pain in the ass.

That different form factor can change the way you play and inspire you to do things you might not have done otherwise.

Absolutely. Our hope is that people develop a way to do something that can only be done with our guitar. But guitar players are a very conservative bunch, no matter how avant-garde they think they are. It has to be a Strat, a Tele, or a Les Paul. That’s what everybody hears, that’s what everybody wants to hear, and that’s what everybody’s used to. We’re basically trying to ease it into the sphere of acceptable items to have on a guitar. We weren’t trying to be gimmicky. First and foremost, we designed the Relevator to be comfortable as a guitar itself. We stay within conventional scale lengths, neck dimensions, body dimensions, body weights, and hardware.

Besides the lack of footswitchability, what are the drawbacks?

Accidentally engaging them or having a technical flaw. I think the major drawback would be feeling intimidated until you’re totally down with it—getting confused by all the things you’re looking at.

How do you minimize the likelihood of accidentally engaging an effect? Are there certain types of switches or knobs?

The biggest thing is having a way to visually tell whether something’s on, and also a tactile way. The on-off buttons on our guitars are like footswitches—a push-push situation. When you push it and it comes up, the effect is on. We made it so that the top of the button is very, very close to the surface. It’s not something that a pick should actuate unless you’re right on top of it. Do you remember the Fender Elite Stratocaster from the ’80s?

Yeah.

Instead of a slider switch, it had three pushbuttons. We found that switch. We have bins and bins of graveyard parts. We tracked it down and got some more after we decided that it was the one we wanted to use. It was hard to get buttons for them, so we ended up having to make our own. That kind of freed us up, because then we could do whatever color we wanted. The pushbuttons and how we mount them are substantially different from the way Fender did it, but it has worked out really well. It’s just a little double-pull, double-throw switch. They’ve been super reliable—I don’t think we’ve had one go bad.

The beginnings of a new BilT beast.

Which switches do you recommend for players who want to install effect on their own guitars?

The easiest way is probably either a push-pull or a push-push potentiometer switch, like a double-pole, double-throw [DPDT], coil-tap-type switch. Most guitar effects use those same basic components. The footswitch is often DPDT, and you can use the same configuration on your push-pull or push-push pot. We’ve come to like the push-push ones, because instead of having to grip and pull up, you just tap it and it pops up—it’s fast.

Have you ever shoved a Relevator into a skeptic’s hands and said, “Just try it”?

Oh yeah.It’s pretty amazing how quickly it becomes intuitive.It can be as complicated as you want to make it, or as simple as you want to make it. Our thought was that we’d get it to the people who could legitimize it for us rather than just trying to sell it. We’d much rather make it about people playing it than about us telling you how awesome it is. From that perspective, we’ve been willing to wait it out. I think it’s served us well, especially as an attention-getter, because it’s going to create a response in your average player upon first sight. When we first launched it, I had to develop some thick skin pretty quick.

What’s the most common reaction when someone plays a guitar with built-in effects for the first time?

It’s kind of a cross between delight and sheer panic. It’s fun to watch people disappear into that focused zone once they start to feel a bit of confidence with what everything does. Once they get over the panic, they dive into that “I need to understand this” mode. That brings me back to another point: We wanted to make the guitar completely transparent. We wanted a guitar that plays good, sits well, hangs on your body right, and is comfortable, so that it basically fades out. We wanted to use high-quality components and pickups as well. As far as we’re concerned, the pickups are the heart and soul of your tone. Once we address all those variables, the only thing left is technique. What wanted to make sure that if there’s a problem, it’s you—not the guitar.

How much does all that routing affect the guitar’s resonance and sustain?

I don’t think it really hurts anything. We put everything in the Relevator’s back cavity, which is roughly the same size as a tremolo cavity. It’s not massively out of the ordinary, like the big trapdoor on the Electras or like a Moog guitar. We wanted to keep it as traditional-looking as possible so that people would accept it. That said, we went with something that people had never seen before. Only the nerdiest of nerds knew what a Marauder was, although that’s changed now.

How much DIY building experience is necessary for someone who wants to put a circuit or two in their guitar?

If you can route a pickup cavity or install complicated hardware, that’s one set of skills. If you understand how the basic electronic components of a guitar work—like potentiometers and switches—and you can draw a wiring diagram of a guitar and how the controls work off the face of an effect circuit board, then you can give it a shot.

Any suggestions for players who don’t have access to a router?

Find a good shop and be persistent. You just have to find somebody who can do all those things for you. I certainly don’t count myself among electronics experts. I don’t spend a lot of time understanding the values of all the components that go into any given effect, but I basically know how everything works.

How much should someone expect to pay to put an effect or two in a guitar?

It’s not going to be a hundred bucks. You’ll either get a ruined guitar or $100 worth of nothing. Be prepared to hit at least the $400 to $500 range. When we have people request a new, different effect, we immediately throw in a $400 charge plus the cost of the effect, because of the time needed for layout and making sure everything goes right. Usually we don’t make any money off of that charge.

YouTube It

Des Moines indie-rock outfit the Envy Corps plays their 2011 album, It Culls You, in its entirety. At the 12:26 mark, guitarist Brandon Darner wigs out on with his original Tim Thelen-modified “Monster” Telecaster.

And how long should they expect it to take if they do it themselves?

That’s a tough one. With all the research, drawing everything out, laying out how you want things done, ordering the parts, taking it all apart when it doesn’t work, putting it all back together, and taking it all back apart when only one thing works … I would plan to put a good 20 or 25 hours into it.

You didn’t say “if” it doesn’t work….

Yeah, when you have to take it apart. I’m on a lucky streak right now. I’ll probably regret saying this, but it’s been a long time since a Relevator has not worked the first time, though at this point it’s a rote, repetitive experience.

What’s the most common reason something doesn’t work?

I might put a component in backwards on the fuzz, or wire an in to an out, or a solder joint might come loose. There are lots of solder joints in a Relevator.

Do you think the average local repair guy could pull this off?

If someone can route and install a Floyd Rose tremolo, they probably have enough skill to map out and route a cavity that would allow a circuit to be installed. If they can make custom pickguards, that’s another indicator. Or if they can install a humbucker in a standard Telecaster neck position. Those are ways to tell whether there’s a little bit more going on than just setups and clamping broken headstocks.

Book of Relevations

BilT Guitars’ Tim Thelen reveals the inner workings of the Relevator’s apocalyptic tones.

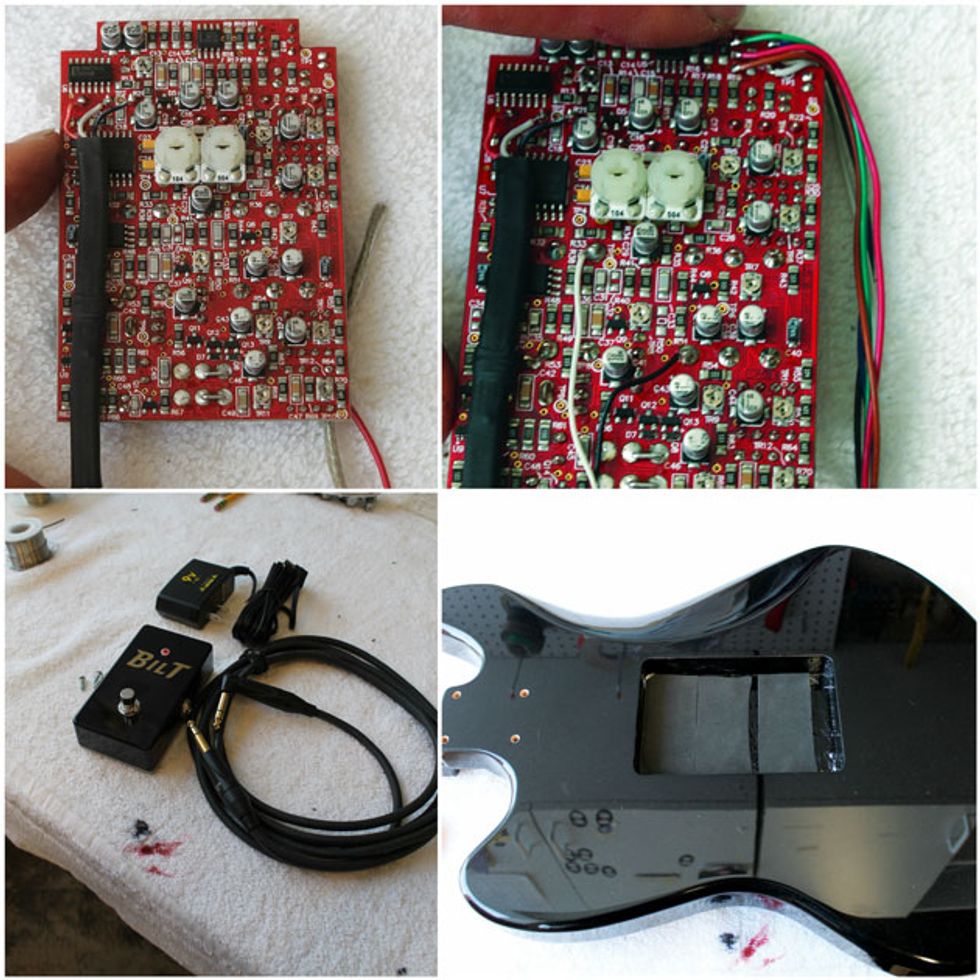

The parts, components, and tools needed for the job ahead (top left). The Relevator’s assembled bass-bout control plate (top right). Hand-drawn Relevator effect-circuit diagrams (bottom left). Circuit boards and parts for the fuzz circuit that BilT designed for the Relevator (bottom right).

Populated fuzz circuit boards (top left). The Relevator’s pickguard and control plates are assembled and ready for wiring (top right). The lower treble-side control plate houses the main volume and tone controls, input jack, and fuzz-circuit controls. The shielded, 10-wire cable routes everything to the fuzz circuit board in the back cavity (bottom left). The wired lower control plate (bottom right).

The Relevator’s wired bass-bout control plate with 3-way pickup selector and Jazzmaster-style rhythm-circuit slider (top left). The upper treble-side control plate and MXR Carbon Copy delay pedal before disassembly (top right). While a desoldering tool is recommended for removing larger Carbon Copy components like the footswitch, wire clippers are better for preventing damage to fragile items like the modulation switch and delay potentiometers (bottom left). Removing the footswitch with a desoldering tool (bottom right).

Book of Relevations

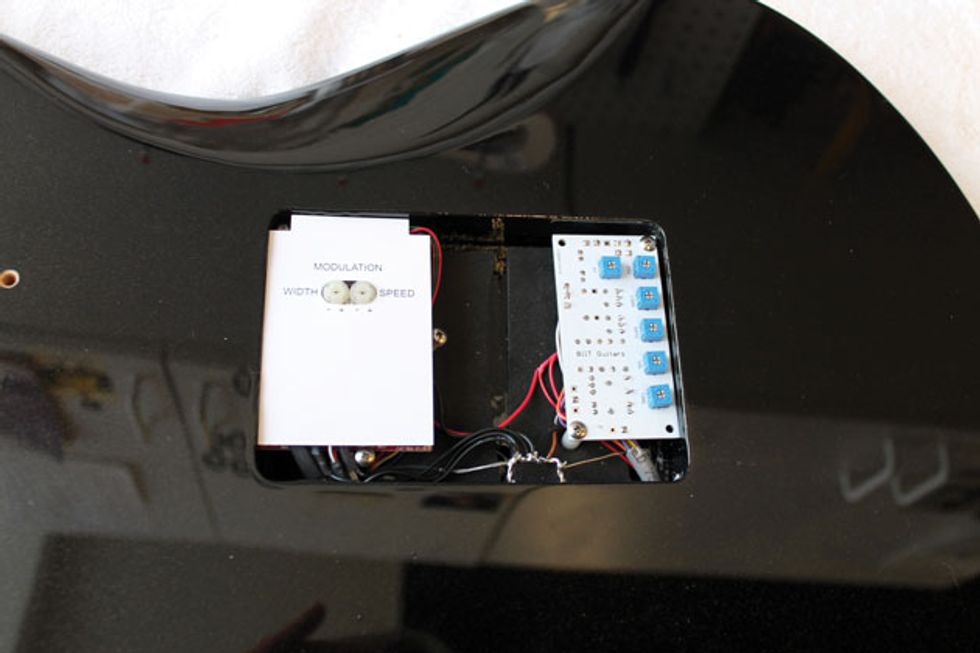

Wiring a harness that will reach the delay’s rate control on the face of the guitar. Each wire needs to be individually shielded to prevent crosstalk noise (top left). This shielded, six-wire cable connects to the modulation switch. (Note the black and white shielded wires connected near the middle of the circuit board. These are for the on/off switch on the control plate. We hardwire the effect to be on and use the signal wires to engage it—effectively making this a true-bypass delay—top left.) Relevator effects are powered by a TRS (tip-ring-sleeve) cable running from the guitar to an outboard stompbox that sends 9V current from a DC wall plug to the ring portion of the jack. The pedal’s LED indicates when the power is on. When the pedal is deactivated, the guitar functions normally with the effects’ on/off buttons in the off position (bottom left). A rear cavity in the back of the guitar is lined with a thin layer of neoprene that acts as a protective bed for the circuit boards (bottom right).

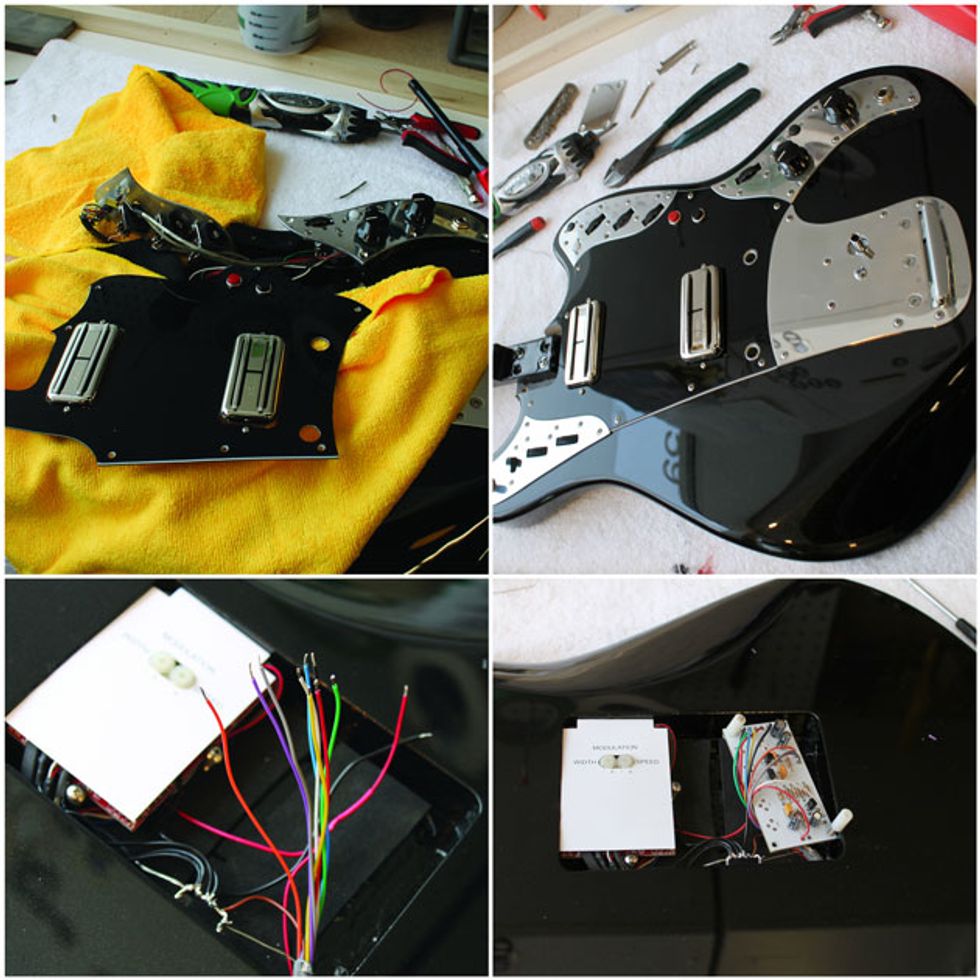

The delay circuit board nested in back, with the harness fed through to the front of the guitar (top left). A ground bus (the rectangular coil of twisted wire) is screwed to the side of the rear cavity and into shielding paint that was applied before the black final coat. This allows us to tie all shielded wires and circuit grounds to one spot, which is then connected to ground on the input jack (top right). The pickguard and other panels are ready to be installed (bottom left). Feeding the fuzz cable back to the rear cavity (bottom right).

Connecting the signal wire to the delay on/off switch (top left). With the plates and pickguard assembled and secure, the Relevator is ready for final connections (top right). The various leads from the fuzz circuit’s harness are stripped, tinned, and ready to wire to the board (bottom left). Fuzz leads are connected and the board is ready to be flipped over and screwed to the cavity (bottom right).

The fuzz circuit after being secured with screws.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)