English guitarist and songwriter Michael Chapman released his second album, Fully Qualified Survivor, in 1970, when he was still in his 20s. It was an important milestone in his career. Legendary British radio personality John Peel called it his favorite album of that year, and its title was somewhat prophetic.

How so?

Because today, at age 76, Chapman is still at it. He is still working, recording, and this year he’s celebrating his 50th anniversary as a touring musician, with almost as many albums to his credit. He also isn’t slowing down. He has a spring tour planned, recently released an album of solo guitar improvisations, and has an English/Hebrew collaboration in the works with Israeli singer/songwriter Ehud Banai. “We sing the same songs,” Chapman says about the project. “But I do the English verses and he does the Hebrew verses.”

Over the years, Chapman, whose primary instrument is fingerpicked acoustic guitar, has combined his penchant for songwriting with an adventurous spirit. He’s tried everything from synths to New Age to howling feedback to ambient soundscapes. He’s toured with a floor full of pedals and a worn Fender Bandmaster, although nowadays travels with nothing but a guitar. He’s also collaborated with a disparate array of artists—or, to paraphrase his publicist, “Name another musician who has played and recorded with Mick Ronson, Elton John, and Thurston Moore.”

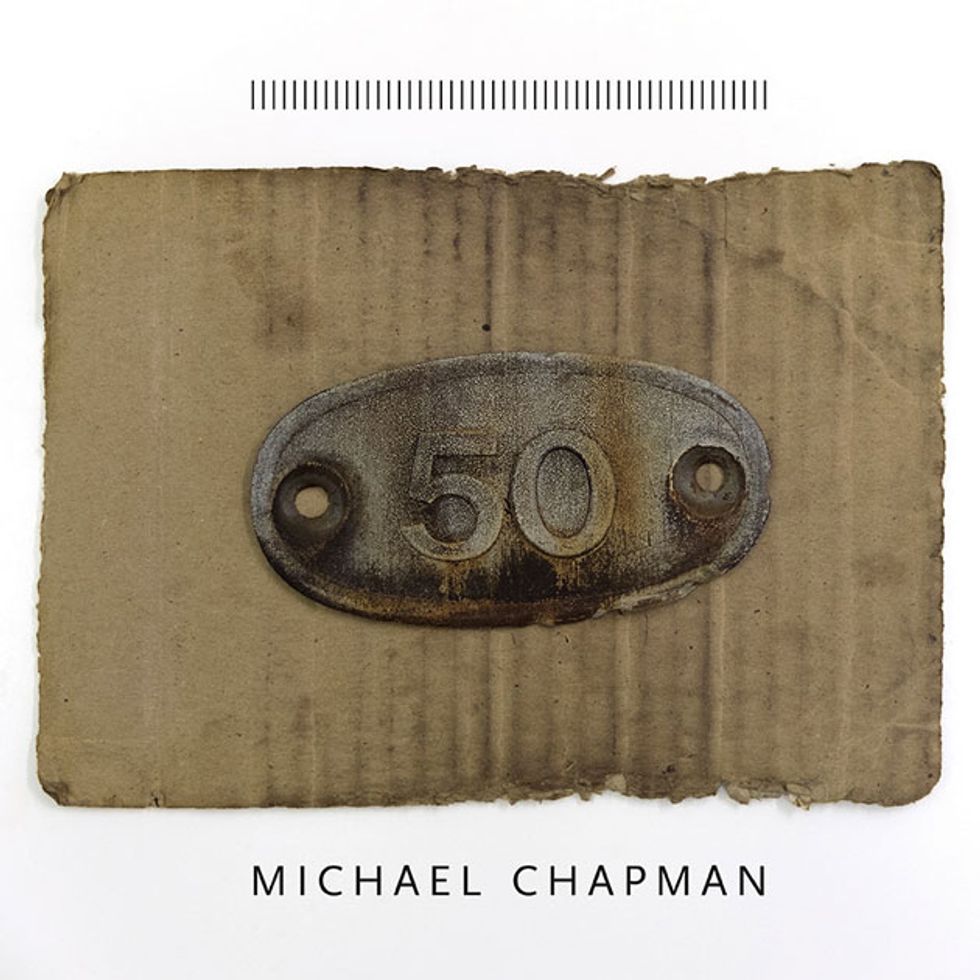

His latest release is called 50 and, as the title implies, is a nod to his half-century on the road. It was produced by Steve Gunn and is a departure from how Chapman usually does things. “One of the things we thought I should do was to give away control,” he says. “The last five or six albums I’ve done, I done near played everything apart from the drums.” 50 features Gunn, multi-instrumentalist Nathan Bowles (Pelt, Black Twig Pickers), guitarist/keyboardist James Elkington (Jeff Tweedy, Richard Thompson), bassist Jimy SeiTang (Rhyton), and guitarist/bassist Jason Meagher (No-Neck Blues Band), who engineered the sessions. Singer/songwriter Bridget St John also vocalized on the album, which puts Chapman’s timeless acoustic and electric guitar in a contemporary musical framework. The project was very much a collaboration, but the process was sometimes frustrating. “It was swings and roundabouts,” Chapman says. “One day I was feeling great about it and the next day I was damn near suicidal. It took me a while to get used to it, because it’s absolutely not the record I would’ve made. But I’ve got used to it now and I think it’s great.”

These days, Chapman lives in Northumberland, just south of the Scottish border, and although he’s something of an elder statesman, he still likes to take risks. “I just keep pushing the envelope,” he says, “to see what’s out there.”

PG spoke with Chapman about recording his new album, his decades-spanning career, discovering his style, and what he’s learned over the years. We also talked about some of the amazing guitars he’s owned and played and his love/hate relationship with pedals.

When did you first start playing guitar and what drew you to the instrument?

I started in 1956 because I didn’t like my history teacher. I conned my mother into buying me a guitar, which was £6 (about $10). I used to sit in the back of history class playing the guitar to annoy him. And the other thing … you ask any guitar player in the world, “Why did you want to have the guitar?” It was because you got prettier girls.

What kind of music were you listening to?

In England, there was a skiffle craze. [A typical band] was three acoustic guitars, a tea chest bass, and a washboard for the rhythm section. For about £20 you could have a band. There were a lot of commercial skiffle records made in England, but we didn’t do that. We were addicted to a guy called Ken Colyer. He was a New Orleans [style] trumpet player in London. He’d actually been to New Orleans and was deported back to England. We gave him heroic status because he’d been to see these old black guys and especially because he’d been jailed and deported. It couldn’t have been any better than that. He came back with all these songs he’d collected—Lead Belly songs and others—and he did them in a very original way with guitar, banjo, maybe a washboard, and maybe a bass if they were lucky. We thought that was authentic and that was the road we went down. We didn’t like those pop skiffle records, which were very fashionable at the time and sold a lot of records. They were too commercial for us.

Did you start fingerpicking at that time or did you play with a flatpick?

I played everything with a flatpick, which was very confusing when I heard [fingerstylist] Big Bill Broonzy. I was playing Broonzy with a flatpick until somebody said, “No, hang on—try it this way.” I finally managed to get my thumb to do the Broonzy thump at the bottom and then I was off and running. But I never learned to do anything else. I still only play with a thumb, index finger, and pinky. I never learned to get the others going. People have tried to teach me and it won’t go. But I’ve gone this far doing that, so it’s okay.

But you do use a thumbpick and fingerpick.

I have a plastic thumbpick and a steel fingerpick. In those days, we were playing in church social halls and the back room of a pub. There were no PAs and there were no microphones, so the louder you could get the guitar, the better.

Did you take lessons, learn the rudiments of music theory, or learn how to read music?

I still can’t read or write music. In those days, there was one book, Play in a Day, by a guy called Bert Weedon. He said he could teach you to play the guitar in a day. Well, he was lying. He was the first star guitar player to play instrumentals on TV and we watched him, but we’d heard jazz guys before him. I’d heard Django Reinhardt by then and Bert Weedon, plodding around on this guitar, was a joke. There was no way to learn. You had to figure it out. I’d play records … I didn’t know there were two guitar players on them and I would try and learn the lot.

Meaning both parts?

I went through maybe a year-and-a-half of a Django Reinhardt fixation. I learned to play all the Django Reinhardt solos, which taught me how to play really fast. I got employed a lot as the fastest guitar player in town. It was rubbish, but it was really fast rubbish.

When did you start writing your own songs?

I walked into a folk club one night because it was raining—it was down in Cornwall—and they offered me a job playing six nights a week for the rest of the summer. All of a sudden, without any pre-planning or anything, I was a professional musician. I was playing Big Bill Broonzy, Jimmie Rodgers, Thelonious Monk, Jimmy Giuffre—all kinds of things. One night I was driving home, it was about 2 o’clock in the morning, and I was too tired to drive any further. I went to sleep in the car and woke up with these lines for a song, “Oh my life goes by so easy/My days they pass so well.” I put a couple of chords on that and then I said, “Shit. I’ve written a song. Wow.” I didn’t know that people like me could write songs. It never occurred to me. That opened the floodgates and for three years after that I was writing nearly all the time. I threw a lot of it away because a lot of it was crap. But that was how that started: because I was too tired to drive.

For 50, Chapman collaborated with a fresh crew of musicians, including (from left to right) producer and guitarist Steve Gunn, multi-instrumentalist Nathan Bowles, and keyboardist-bassist Jimy SeiTang. Photo by Constance Mensh

Did you play those songs at your nightly gig to try them out in front of an audience?

Yes. I was working in folk clubs because I wanted to play acoustic. I played a lot of electric in jazz and rock ’n’ roll bands, and I wanted to play acoustic. Folk clubs were the only place you could do that because the audience would be silent. There were still no PAs. In those days, folk clubs were a very, very broad church. I mean, that first night in the folk club that I went into, I played three things: “’Round Midnight” by Thelonious Monk, “The Train and the River” by Jimmy Giuffre, and Jimmie Rodgers’ hobo song [“Hobo Bill’s Last Ride”]. You couldn’t do that now. They stopped listening to such a breadth of music.

In the late ’60s, when you put out your first albums, you played the acoustic parts and had someone else play the lead parts on electric. Why didn’t you play those yourself?

Because Gus Dudgeon, the producer, didn’t like my electric playing. It was still too jazzy for him and he didn’t want that.

Mick Ronson plays the lead parts on Fully Qualified Survivor. How did you get him?

He lived around the corner. He was in a band called the Rats. I took him down to London to do the Survivor album and the record company said, “No, we’ve got all these London guys lined up.” I said, “I’ve got a gardener from Hull who will play their asses off.” They finally relented and, of course, he just blew everybody away.

Michael Chapman’s Gear

Guitars

• 1951 Martin 000-17

• Martin D-18

• Gibson ES-175

• Gibson J-50

Strings, Picks, and Slides

• Elixir Light-Medium strings (.012–.056)

• Plastic thumbpick and metal fingerpick on index finger

• Piece of pipe from his mother’s kitchen

• Wedding ring

And those were his first recordings?

Yeah. I introduced him to Gus, who introduced him to David [Bowie]. When I did the Survivor album, I wanted Mick to be in the band that I was going to take out on the road to promote it. But he wouldn’t leave the Rats. He was a very genuine and honorable bloke. So when David turned up and took all of them, then he went. He turned them into the Spiders from Mars, so Mick didn’t have to split up with his mates.

Let’s talk about some of the guitars you’ve owned over the years. Start with the black Fylde guitar with the vine inlay.

That was the only black one they ever made. I ordered that custom-built and I said I wanted it made with no natural bass response in the guitar. Roger Bucknall said, “What the hell for?” I said, “Because I want to play it loud.” The more bass response a guitar naturally has, the more problems you have putting it through PAs and monitors at rock ’n’ roll volume. It was built to do a specific job. And it did it very successfully for a few years.

You use amplifiers as well.

No. I used to. I used to carry around that big Fender Bandmaster. We had big PAs, but we didn’t have proper monitor systems for quite a long time. It’s only recently that monitors have caught up with what you can put out front. I wanted to hear myself onstage. Now, I just plug the guitar straight into the DI and turn it up.

What do you use for a direct box?

Whatever they have. I’ve got it down: It’s me, a guitar, a lead, and a packet of sandwiches. That’s my on-the-road kit.

Do you still use your Martin D-18?

No. That was on the road with me for a long, long time. But it got damaged twice, both times by Air France, so now it’s just in the front room. Hendrix actually played that guitar.

How did you meet Hendrix?

I didn’t. There was a club in London that we used to do all-nighters on Friday and Saturday nights, from one until 7 in the morning. That was usually the eighth gig of the week so you were tired when you got there. On that particular night, I was asleep in the car when Hendrix walked in, picked up my guitar, played three songs, and walked out. I missed it, but I’ve still got the guitar.

What are you using now?

My main working guitar is a 1951 [Martin] 000-17, which is a fabulous little thing. It’s all mahogany, obviously, like the 17s were. If you think about it, in 1951, there was no wood around. It was just after World War II, the Korean War was about to kick in, so it was probably made out of old furniture. Some of the wood in that guitar could be 200 years old. In 1951, that guitar was $27, but it sounds fantastic. The definition is just stunning. And it’s small and it goes in the overheads on airplanes.

When did you start using different tunings?

That was, like, ’66 or early ’67. Ralph McTell … I don’t know whether you are aware of Ralph. I don’t think he’s ever really come over to America, but he’s one of the best ragtime players I’ve ever heard. He played me some [Bahamian guitarist] Joseph Spence records and showed me how to drop the bottom string to D. Joseph Spence always played in dropped D—or he did when he was alive. That started me off. I tuned the whole thing to a chord—a chord of D, I think—and started messing about trying to find chords. I tried G. I tried C. Then I tried G-minor and all kinds of weird things just to see what happened.

I just did an album for Steve Lowenthal, for VDSQ Records in New York. Basically, I tuned the guitar to anything. I would have to listen to the record to know what the guitar was tuned to. The album is called Homage and is an homage to various guitar people. The first track is a homage to Orville Gibson. I wanted it to sound like the Gibson harp guitars, so the bottom string was down to A-flat, which was almost dropping off.

You use both traditional tunings and tunings you’ve invented?

Yeah. If I’m gigging I like to know what the tunings are. I only use about four or five now. It used to be silly, the different tunings for every song. People don’t want to spend half the evening listening to you tuning up.

When did you first start playing slide?

I was gigging quite a lot early on with a guy called Mike Cooper. He played a couple of Nationals: one in normal tuning and one in G. He had a Blind Boy Fuller fixation and he played slide. I figured, “I think I can do that.” I’ve always been meaning to teach myself to play slide in normal tuning. One of these days.

When did you start playing slide with your wedding ring?

Very early on. It’s a bit of a gimmick really, isn’t it? It’s nice to slip one in there and people go, “What the hell was that?” It’s never in tune—it is kind of ragged but right—it’s five strings in tune and one out. It’s interesting.

You’ve done a lot of experimental work over the years as well. A few examples are the early synths on “Lescudjack,” or Heartbeat, which has been labeled New Age…

Then I did that stuff for Thurston [Moore], the stuff with the No-Neck Blues Band, and the feedback albums.

You’ve always been adventurous.

For me, that works. I’ve got a very low boredom threshold. As far as the public is concerned, it’s confusing, because, “What the hell is he going to do now?” It’s not as though I worry very much about the public.

What are some new things you’re experimenting with?

I came across a lap steel a while back with only five strings on it that isn’t tuned to anything. I’ve been messing about with that. There are quite a lot of people that I do gigs with … they play acoustic, but they’ve got a pedalboard the size of a kitchen table. They are doing interesting things with pedals. I went to see Bill Frisell and that was just astonishing. I did a gig with Fred Frith as well and he had 27 pedals. I counted them.

Just for himself?

Yeah. And the stuff that he was coming out with, because he knew what they did and he knew when to use them. I had quite a few at one point, but I thought, “This is getting more like tap dancing than playing the fucking guitar.” So I put them in the bin.

You’ve done a lot of stuff with feedback, too. Do you find the acoustics feed back differently than the electrics do?

As long as the monitors are loud enough, at the end of the gig I like to finish up with some feedback out of the acoustics. They say, “It can’t be done.” Well, don’t tell me it can’t be done. For the feedback stuff I did with Thurston, I was using my Gibson ES-175, because they feed back quite early. I used to have a beautiful ES-330 and that fed back really early, but in those days, that was the last thing I wanted to do.

What capos do you use?

I don’t use them. I think they destroy the intonation of the guitar.I see old photographs of myself and I used to always have a capo on the second fret. I have no idea why. From the nut to the bridge on the guitar is that distance for a reason. And it’s one less thing for me to leave behind.

More room for sandwiches?

Yup.

Chapman cut his tracks for 50 and hit the road, leaving overdubs and mixing to producer Steve Gunn and his players.

Perfect Takes: Steve Gunn on Producing 50

Guitarist, singer, and songwriter Steve Gunn produced 50, Michael Chapman’s latest release. “I first met Michael around 2008, through guitarist Jack Rose,” Gunn says. “Jack and I were both living in Philadelphia and he was touring with Michael quite a bit at the time. I was a big fan of Michael’s older records and I was excited to meet him. Sadly, Jack passed away soon after I met Michael, and our first performance together was at a memorial service for Jack in New York City. Since then we’ve done quite a few shows together in the States and Europe.”

The 50 album was recorded at Black Dirt Studio in Westtown, New York. “Michael brought some great guitars to the studio—particularly his old Gibson J-50,” Gunn says. “Michael’s playing is still really strong and he would do these perfect takes of each song, one after another.”

“I only stayed for the recording,” Chapman adds. “Steve and Nathan [Bowles] were there for a couple of extra days after I’d left doing overdubs and things.”

Chapman is celebrating his 50th anniversary as a professional musician, but he isn’t crusty or set in his ways. “He was very open to us interpreting his songs the way we wanted,” Gunn says. “He sent along some rough demos and we discussed the arrangements beforehand. We collectively worked hard to get things right before final tracking. Michael was never demanding.”

Not that Chapman found it easy to relinquish the wheel. “It was difficult for me to give away control, but it works,” he adds. “That was the point, ‘Don’t make just another Michael-Chapman-studio-down-the-road album.’”

“Michael is a humble, schooled, and fearless player,” Gunn says. “His sensitivity as a songwriter and dedication to being a touring musician is continuously inspiring.” Gunn was also inspired by Chapman’s outlook and desire to keep growing as a player. “It’s amazing to me how present Michael is with his playing. He’s constantly looking forward and pushing the limits of what he can do. A lot of players of his generation are comfortable with playing the old songs the way they have always played them, but not Michael.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.