R.L. Burnside loved tossing off dusty one-liners like a juke joint Henny Youngman. “I ain’t drinkin’ no more,” he’d declare, pause a beat, and resume “but I ain’t drinkin’ no less, neither.” And he’d toast his audiences with “Look out stomach, look out gums, over the teeth and here it comes.”

But his music was even dustier. It was anchored in Africa and emanated from the soil he worked for most of his life in his native North Mississippi, then amplified by regional players who mesmerized him as a young man, including the well-traveled Fred McDowell and the obscure Ranie Burnette. And it was polished by the sound of the records that John Lee Hooker and Muddy Waters made in the ’40s and ’50s, which Burnside heard during his two or three years in Chicago and trickled back to Mississippi after he returned.

Eventually, in the 1990s, Burnside would regularly tour the world himself, release well-received albums on the Fat Possum label, and establish a legacy that still reverberates in the blues realm and in the roots-rock underground. But there were many decades in between where he raised a family, worked on farms, was a bounty hunter, played juke joints and house parties nights and weekends, and even spent a short stretch in Mississippi’s notorious Parchman Farm penitentiary for killing a man with his rifle in a dispute over a still. Despite that act of violence, Burnside cast a spell over nearly all that met him, who typically recall him as warm, funny, and openhearted.

They also recall him as a 6-string badass. Burnside played hard, heavy, and loud, and loved the sound of the electric guitar. And like so many rural bluesman, he wasn’t as fussy about tuning and tone as wanting to tell a story—to deliver a message, whether it was about existential loneliness in a song like “Just like a Bird Without a Feather,” which was first captured in a 1967 field recording, or about the comedy of romance portrayed in his thrashing “Snake Drive,” best recorded on 2001’s live Burnside on Burnside, with its playful tagline “love is the devil, but it can’t get me.”

Burnside’s Fat Possum albums, as well as the label’s recordings by his neighbor Junior Kimbrough and earlier albums by their contemporary Jessie Mae Hemphill, brought the North Mississippi hill country style of blues to the world at large. Until then it was known almost exclusively to the area’s residents and a small, cloistered circle of fans—although McDowell was an earlier proponent of the style, before its regional nametag solidified. Burnside upped the ante on the often droning, hypnotic approach that holds a distant echo of small African drum-based ensembles in its static rhythms and frequent one-chord song structures. He dressed it with broad-voiced, laconic slide guitar that added heat lightning to his deft, thick-boned fingerpicking, which displayed an almost lazy yet inscrutable mastery. And on top of it all was his clear, powerful voice, which could sail to heart-piercing falsetto in an instant. Add to that the secret of every great diplomat, charisma, and it seems he was practically destined to carry this music out of his little corner of the American South. But here’s how it happened, more or less.

Burnside was born on November 23, 1926, somewhere in Lafayette County, Mississippi. Accuracy was not a strength of the state’s record keepers then—especially regarding African-Americans. Reports also vary about his given name. It was either Rural, which seems most likely, or Robert Lee. Some of his close friends called him “Ru.” His father abandoned his family when Burnside was small, and he grew up with his mother, grandparents, and siblings.

“Chopping cotton—that’s what my family did,” Burnside related when I first interviewed him in 1993. “That’s what I did until I got to be 18 or 19, and then I moved to Chicago.” But big city life and the violence there that claimed his father, uncle, and two brothers within a two-year span—chronicled in his song “Hard Time Killing Floor” on 2000’s Wish I Was in Heaven Sitting Down—sent him back to Mississippi, where he met and married his wife of 56 years, Alice Mae. Eventually they would settle in Holly Springs.

“There wasn’t much goin’ on here,” he recounted. “Sharecropping and plowing mules. Long days. I tried picking up the guitar whenever I could. I loved guitar music. I tried harmonica, because it was easy to take around, but could never play it. I was 22 before I could make any chords on the guitar.

“The first thing I learned was acoustic. In those days it was quieter and there wasn’t any traffic, so you could hear those acoustic guitars for miles before you got to the house party. Nowadays, without an amplifier you ain’t doin’ nuthin’. I get hired to do songs with acoustic guitars at festivals, but the electric guitar is more soulful.”

Before his own playing got soulful, Burnside wrestled with the instrument for years—staying up into the wee hours even though he had a hard day of farm labor ahead. He often went to Fred McDowell’s house in Como to sit at the master’s feet and absorb. McDowell’s repertoire remained the foundation of Burnside’s style throughout his life.

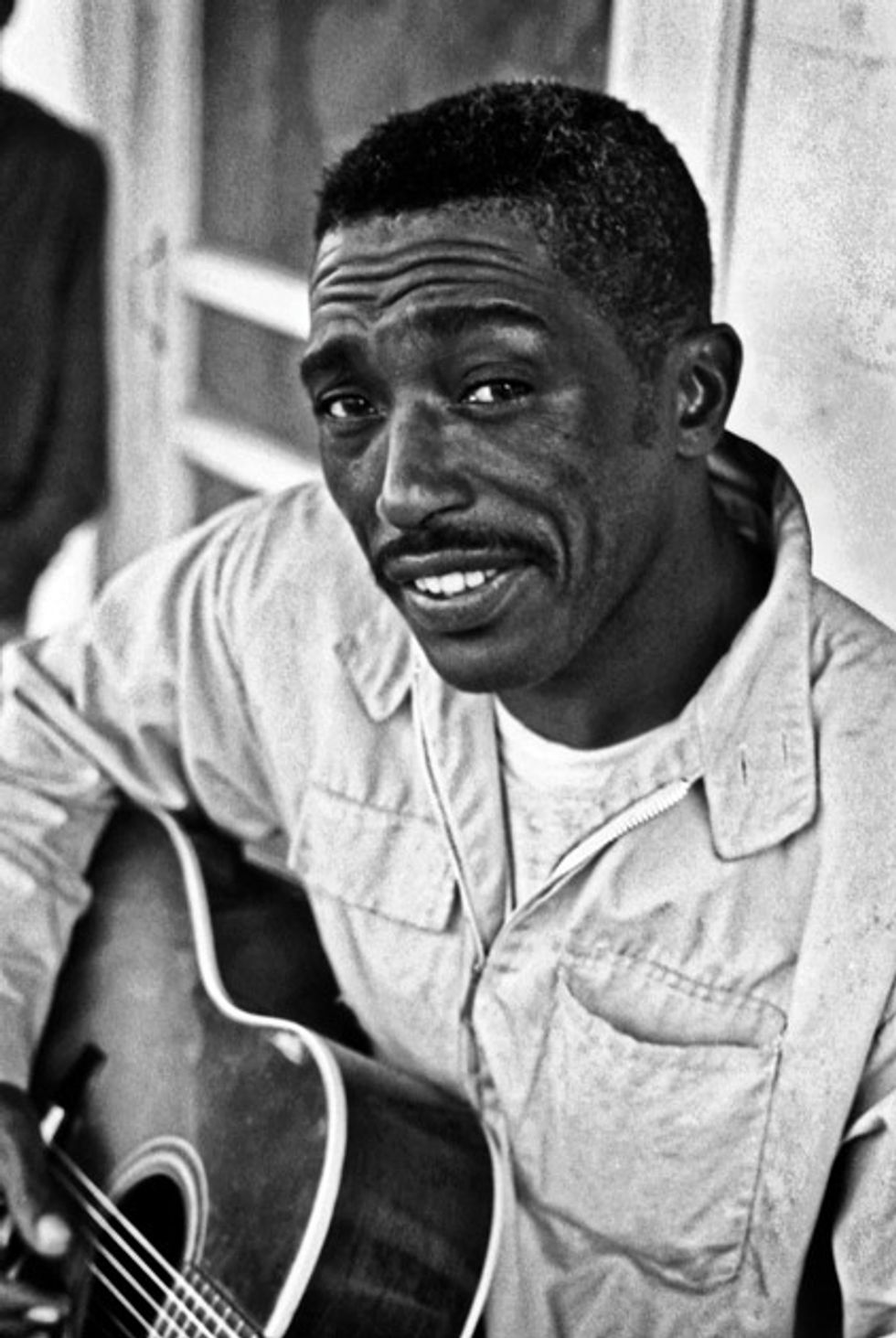

Eventually Burnside began playing house parties on his own and word of his hard-developed prowess spread. That led to his first recordings. In 1967, a young blues fan named George Mitchell was on a quest to document unknown musicians in the rural South. When Mitchell’s attention turned to Mississippi, a mutual friend of Burnside’s and McDowell’s, Othar Turner, who led a fife and drum band, eventually directed him to Burnside. Mitchell found Burnside driving a tractor, cutting down after-harvest corn stalks in the searing sun. “He guided the tractor in our direction, shut it off, and stepped down smiling,” Mitchell recounts. An appointment was set to record Burnside at his home in Coldwater that night.

“What was my reaction when he started to play? Man, goddamn he’s good! It was unbelievable,” says Mitchell. “I was suddenly in heaven. And this cheap-ass guitar I’d brought … he didn’t have one at the time, and I had stopped off in Memphis, and different people tried to play it, and it was, ‘Man, I can’t play music on this thing.’ But R.L. didn’t have any trouble! The only thing he did was to take the E string off of it and stretch it, just to make it have a good sound, I guess. And as soon as he put it back on, he started into ‘Goin’ Down South,’ one of his later hits. I was just amazed. He was a great guitarist.”

That night Burnside cut four songs with Mitchell’s beaten acoustic, including his lifelong staples “Old Black Mattie,” “Goin’ Down South,” and “Skinny Woman.” They initially appeared on the 1969 Arhoolie Records compilation Mississippi Delta Blues Volume 2, but are best heard along with the rest of Mitchell’s 1967 discoveries on the 2008, seven-CD set The George Mitchell Collection Volumes 1–45, which is manna for fans of rural blues.

Mitchell tried to get some gigs for Burnside and brought him to Atlanta to play, but ultimately decided “that wasn’t my job. I was still looking for blues singers.” The Arhoolie album won Burnside some work, including his first trips to Europe, but “I just couldn’t get away from farming,” Burnside said. “At that time I was making about $20 a day driving a combiner, working a week for about $150. I’d go somewhere and do one show and get $400 or $500, but when I needed to go would be the time I’d need to be picking cotton or chopping beans or something, so I gave it up.”

YouTube It

R.L. Burnside displays the essentials of the North Mississippi hill country style in this 1978 solo performance from the Alan Lomax archive. Listen to the African-sounding intro and then hear him take the song home like a fast freight, pulled by the locomotive intensity of his one-chord drive, with single-note embellishments.

“Not drinking any more … or less.” During this May 1999 show at the Cambridge, Massachusetts, House of Blues, Burnside put down his guitar to preach his hero Muddy Waters’ “Mannish Boy” and shimmy across this stage. Photo by Margo Cooper

Before settling on farm work, Burnside did a stint as a bounty hunter, traveling between Memphis, Chicago, and Texas, but stopped after a near miss from a shotgun blast. “Some of those guys don’t plan to go back,” he observed. “It’s a dangerous job.” He also ran a still for a time, with a partner. When their deal went bad, Burnside killed him with a bullet to the head. “I figure it was him or me or my family,” Burnside said. He explained that he was sentenced to a stretch in Parchman, but got out after serving just six months when his employer insisted he was indispensible for bringing in the harvest.

Burnside’s next crack at recording came in 1979 after David Evans, an ethnomusicologist, was hired by the University of Memphis and established the school’s High Water Recording Company with a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. Evans, who’s also an accomplished musician, used the label to cut singles and albums with several of the artists he’d heard in the North Mississippi and Memphis areas. But his project with Burnside, in particular, 1980’s Sound Machine Groove, was a labor of love. Under the influence of the soul and funk Burnside had heard on the radio and on recordings, including those from Stax in Memphis, just 50 miles away from his home, he had formed his first electric band: the Sound Machine. It included his sons Joseph and Daniel, trading guitar and bass, and his drumming son-in-law Calvin Jackson. The group blended those influences with the Mississippi hill country sound, creating short spells of rough-hewn hypnosis fueled by Burnside’s riff mantras and chanted vocals, and pushed by the primal shuffle of Jackson’s drums. Check out “Bad Luck City” on the album or on YouTube for a definitive performance.

Evans fell for that music. “I thought it was more up-to-date, with the younger musicians and an interesting synthesis of his traditional solo country blues with a kind of R&B sound. I thought this was extending the blues into the modern era, and it was something worth documenting and something worth encouraging. I tried to promote that band and got them all sorts of gigs.

“Unfortunately—I say unfortunately—R.L. already had this established reputation as an acoustic artist. I was sort of fighting against that reputation. In the 1980s there just wasn’t music business interest in country blues. People, and in particular blues record labels, were pronouncing it dead.” So the band got little traction, and Burnside stayed with farming to provide for his expanding family.

Evans describes Burnside as “very open and willing to put himself into the hands of others who could take him on gigs. He wasn’t a suspicious guy—at least he didn’t let on if he was, although I think he was aware that there were a lot of shysters out there. I found him to be very intelligent, too. It was a little bit surprising that he lived in such a ‘low-down’ way on a farm way out in the country. But he kept his family together. He had 13 children. That’s a big expense, keeping a family of that size going.”

Burnside’s trusting nature led him into the final chapter of his recording history when he was approached by Peter Lee and Matthew Johnson, two grads from the University of Mississippi in nearby Oxford, who wanted to launch a record label named Fat Possum.

“We wanted to start the label to record R.L., Junior Kimbrough, and [Roosevelt] “Booba” Barnes,” says Johnson, naming three of the spectacular electric bluesmen who were among the genre’s raw-boned rulers in early-’90s Mississippi. Barnes slipped off to Chicago before recording for Fat Possum, which spent the ’90s struggling but today is an indie-rock powerhouse, a source of rare roots reissues, and owner of the Al Green Hi Records catalog.

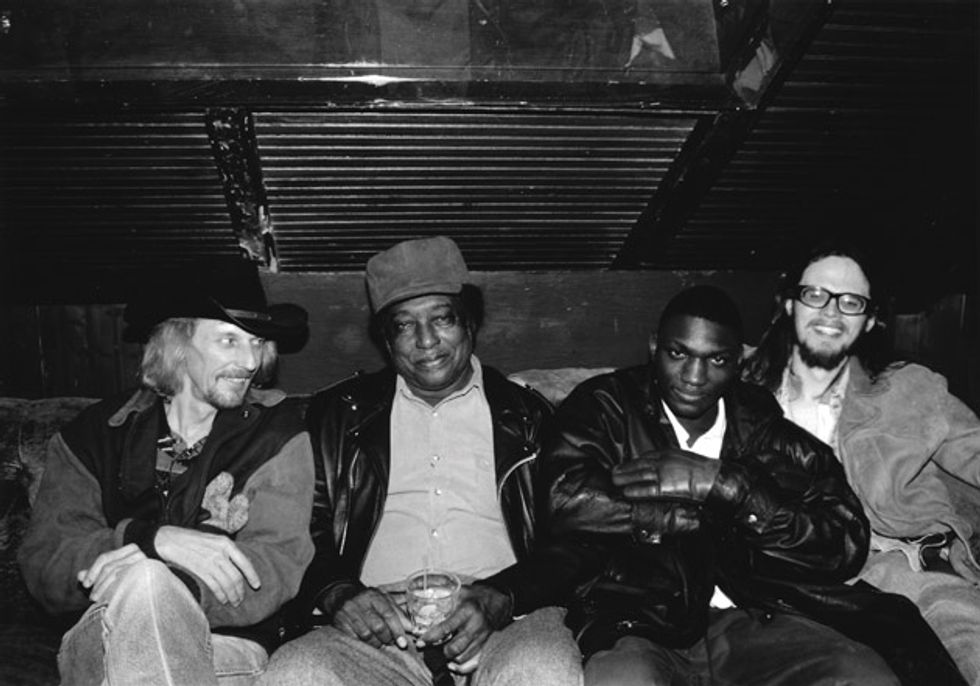

Burnside’s band during this 1997 stop at the original House of Blues in Cambridge, Massachusetts, included (left to right), Kenny Brown, the boss, Cedric Burnside, and guest Luther Dickinson. Photo by Laurie Hoffma

Burnside’s Fat Possum debut, Too Bad Jim, was recorded in 1993 and featured a photo of then-67-year-old Burnside with his dog, Buck, who was killed in a drive-by shooting, on the cover. Inside was a musical revelation: 10 songs packed with meaty hypnotic riffs, sometimes edging toward psychedelia in their potent repetition, and steamrolling slide guitar, jolted by a rhythm section that slammed with equal abandon. It was raw—at times in danger of falling apart, but in ways that were menacing and beautiful. And, again, Burnside’s voice rode his musical bucking bronco, but this time with more edge and age. Within the creases of his singing was the sound of a life lived hard and completely. The album essayed the style of a deep witness, but not everyone found it pleasing. Burnside’s sound was a world apart from the recordings most blues fans heard by the likes of B.B. King, Buddy Guy, Koko Taylor, or even Johnny Winter and Stevie Ray Vaughan. It was messier, nastier, unvarnished. Imagine what it was like for rock fans to hear Black Sabbath for the first time in 1970. That’s what it was like for many traditional blues fans hearing Burnside on his first widely distributed album.

“It wasn’t like we rediscovered him,” Johnson says. “The cooler kids around Oxford knew about Junior’s place. [The juke joint run by Kimbrough where Burnside often played.] The hard part was just getting it off the ground—what was the potential? I thought he might be able to become a big deal. It was clear he wasn’t the guy who wanted to play folklorist bullshit. He wasn’t the acoustic guy. I was like, ‘This guy is just as raw as anyone else and he’s not getting the credit he deserves.’”

Fat Possum started booking Burnside on festivals and in rock clubs, and began securing him a string of agents who worked mostly outside of blues. He was retired from farming and free to travel. And in 1996 he had a breakthrough when one of his fans, blues-influenced punk-garage auteur Jon Spencer, cut an album, A Ass Pocket of Whiskey, with Burnside and took his trio on tour as an opening act. By then Burnside was backed by what became his best-known band, with his grandson Cedric on drums and a lanky blond guitarist named Kenny Brown on second 6-string. Like many rural Southern juke joint bands, they did not have a bass player, but rocked hard regardless. And in their travels, they introduced this sound across the U.S. and in Canada, Europe, and Japan.

A Ass Pocket of Whiskey was pivotal in Burnside’s late-life career, introducing him to a college-rock fan base and allowing him to straddle the blues and rock markets for the rest of his touring years. Noisy and raucous as a gaggle of sotted gremlins locked in a studio with guitars, Marshalls, and fuzz boxes, the album was hated by most blues purists, but remains largely adored by indie-rock inspired listeners and fans of ragged, dirty roots music. So much so that Burnside became a foundational figure in the Deep Blues scene, an underground offshoot with punk rock in its veins that has spawned its own festivals and a tight-knit community of bands.

He also developed a strong relationship with Johnson, who became the sole owner of Fat Possum when Lee left the country. As his career flourished, Burnside’s annual earnings grew into six figures and he and Johnson shared a playful, teasing sense of humor. Burnside’s calls to the label’s offices often began with, “Is the crooks in?”

His music began appearing in films and television—most notably in The Sopranos—and Burnside appeared on Late Night with Conan O’Brien with his band. His final string of recordings also ricocheted between tradition and radical ventures—sometimes on the same album—as Fat Possum continued to push the envelope in a campaign to bring Burnside to more listeners. While 1998’s Come on In was a collection of remixes done by producer Tom Rothrock, 2000’s Wish I Was in Heaven Sitting Down balanced straight-up blues with remixes and textural music. The last unpolished recording of Burnside with his grandson and Brown was Burnside on Burnside, a January 2001 concert taped at Portland, Oregon’s Crystal Ballroom. It was nominated for a Grammy and became his highest charting album, clocking in at No. 4 on Billboard’s blues chart.

But later that year, Burnside’s fortunes shifted, as they inevitably do. A heart attack forced him to stop touring and left him greatly diminished. After a second heart attack the next year, he was visibly weakened and his voice fell to a whisper, as his last recorded public appearance with his acolytes the North Mississippi All Stars, captured on 2004’s Hill Country Revue: Live at Bonnaroo, attests.

Burnside died in St. Francis Hospital in Memphis on September 1, 2005. He was 78. A year later the spirit of his music reverberated through the film Black Snake Moan, in which Samuel Jackson plays a blues singer and guitarist at least partially inspired by Burnside, and Kenny Brown and Cedric Burnside appear as the core of Jackson’s band.

Today, Burnside—who was fond of telling his audiences that he was “proud” they came to see him and embraced his music—remains a revered musical hero with a devoted cult following. His bandmates Kenny and Cedric (who has evolved into an exceptional drummer, guitarist, and songwriter) continue to keep Burnside’s sound reverberating and his legacy alive. He was the gateway to professional careers for both musicians, enlisting Brown as his guitar foil in the mid 1970s and letting his grandson man the drum kit in juke joints starting when he was only 7. R.L.’s son Garry Burnside and his grandson Kent are also busy performers, steeped in the North Mississippi sound.

Cedric, who is now 38, speaks of R.L. with love and reverence. “It was a beautiful thing, growing up with my Big Daddy,” he says. “I’m definitely glad to be part of the Burnside family and to have the history that I witnessed, coming up as a kid. He was the father and grandfather that everybody would have loved and wanted. He treated me as a son, and not as his grandson. He took me under his wing and took me out on the road with him when I was 13, when he could have got anybody. So just for that, I’m blessed and thankful. I never heard anybody say any bad things about him. As a musician as well as a person, he was beautiful within himself.”

YouTube It

Dig the double juggernaut of R.L. Burnside and Kenny Brown on slide, with Cedric Burnside nailing down the groove, from a 1998 French TV broadcast. Burnside often called his take on this Muddy Waters/Robert Johnson-associated classic “Fireman Ring the Bell,” exercising a bit of artistic license.

Playing Burnside Style

Kenny Brown and Cedric Burnside, shown playing at the annual Juke Joint Festival in Clarksdale, Mississippi, are the two leading proponents of their mentor’s style. Photo by Margo Cooper

R.L. Burnside was a powerful musician. He could roll back time or conjure thunderstorms with his playing, and win the hearts of an audience with a single twinkle-eyed smile as he laid into a howling slide line with the ease of buttering toast. But, like many rural blues artists, he was extremely unfussy about the tools of his trade. Often he didn’t even own a guitar, so once he attained a level he was content with, practicing was something only people who wanted to sound like him did.

Like Kenny Brown. At 63, Brown is the most commanding proponent of Burnside’s deft, subjective picking style and powerhouse slide. On his trusty Memphis-built Gibson ES-335, Brown evokes the gutbucket majesty of hill country blues and the songster tradition he learned from Nesbit, Mississippi’s Joe Callicott before he met Burnside. Both are best witnessed at the North Mississippi Hill Country Picnic festival Brown hosts at his ranch in Waterford, Mississippi, each June.

“R.L. didn’t really give a shit about the amp, the guitar, the strings, or the slide,” Brown observes. And over the years he played Westones, Strats, Teles, Les Pauls, Reverends, and all kinds of knock-offs, and sometimes Brown’s ’58 Silvertone with popsicle sticks glued behind the headstock to allow an upgrade to Grover tuners.

“That’s exactly right,” says Cedric Burnside, whose 2015 Descendants of Hill Country was Grammy-nominated. “Big Daddy would get a First Act out of Walmart, and he would play that. He just played whatever he had. And if somebody came along and made a guitar for him, which happened a couple times, he played it, but never had a preference.”

Except for plugging in. “When he would have to play acoustic for all those people in Holland, it was awful,” says Fat Possum’s Matthew Johnson. “He hated that. That was not R.L. But when it came to practicing, what he played, dialing in a sound, or writing new songs, it was like the only person who had less respect for their own craft than R.L. was Marlon Brando.” [Laughs.]

But Burnside’s sound was consistent. “You cannot go back to any of those recordings and differentiate between a Danelectro and a Les Paul with a Marshall stack versus a Silvertone with a Pignose amp,” Johnson attests.

Brown’s journey into Burnside’s style and life began after he saw him at a concert in a cow pasture. “R.L. played as a duo with a guy who didn’t play harmonica, but made harmonica sounds with his mouth. They were the opening act,” he recalls.

“I already knew some open tuning stuff and a little slide,” Brown says. “Joe had showed me how to lay the guitar in your lap and play slide with a knife in open G. But R.L. was playing great slide and in open tuning and standard, and that was the main thing that attracted me to him. And gosh … the stuff I had learned was three-chord progressions, and R.L.’s music would be, like, one chord. There would be changes in the song, but you never did just a standard three-chord progression. And it was heavy!”

Burnside’s sole open tuning was G, which he often called “Spanish,” in the way older blues musicians did and sometimes still do. When Brown met him, Burnside was playing slide with a weathered slice of copper tubing. “Later on, I got him a brass slide. He would use anything. I’ve used everything myself, from a Coricidin bottle to an 11/16ths socket, over the years. I used to do construction work, and if I’d see any plumbers around, I’d always get them to cut me a piece of copper tubing. Now I use a piece of brass, cut so your finger barely sticks out. I got a friend who works in a metal shop.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)