I’m fascinated by family traditions. Much of my family’s were lost in the transition from Poland to the U.S., and to a language barrier. Thus, the details of my grandmother's history as a village healer in her youth are lost. But for musical families, legacies are easier to trace and preserve, thanks to recordings and other documentation.

One of the best examples in American music is the Carter and Cash clan—four generations deep, with hundreds of records and filmed performances between them. The Allman/Trucks/Betts kin are another illustration that spills across generations. But the closest to my heart are the Burnsides, who, along with Junior Kimbrough and his sons, are guiding lights of North Mississippi hill country blues.

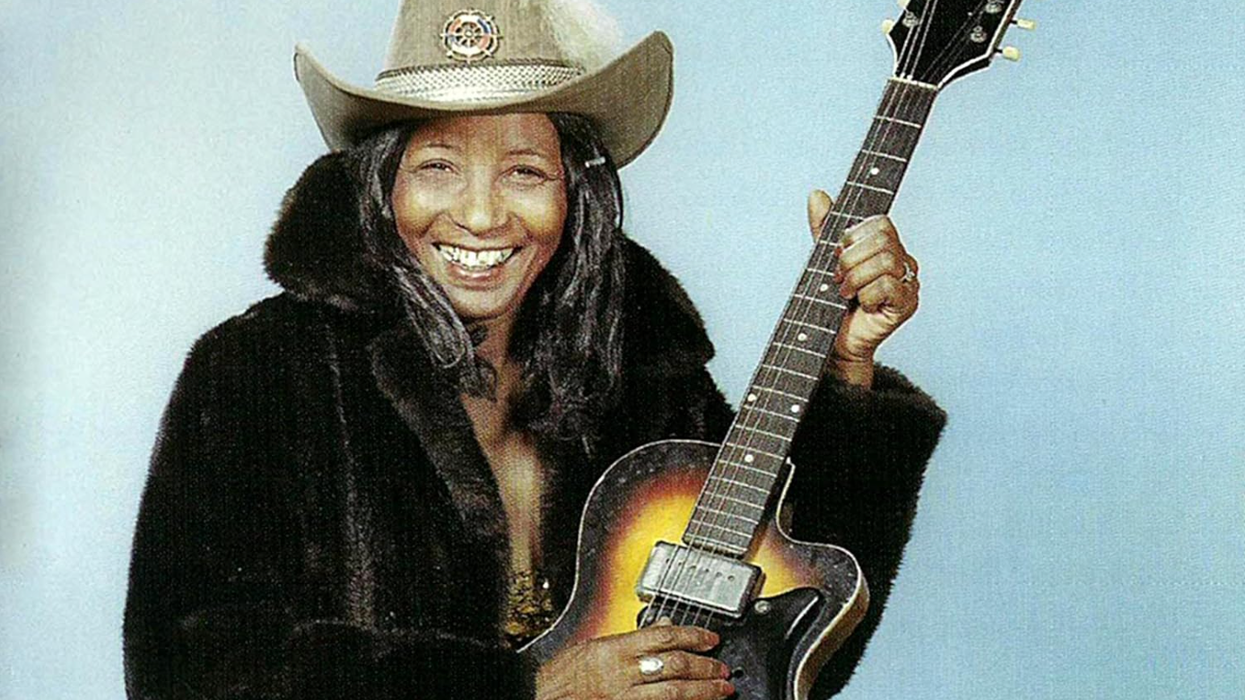

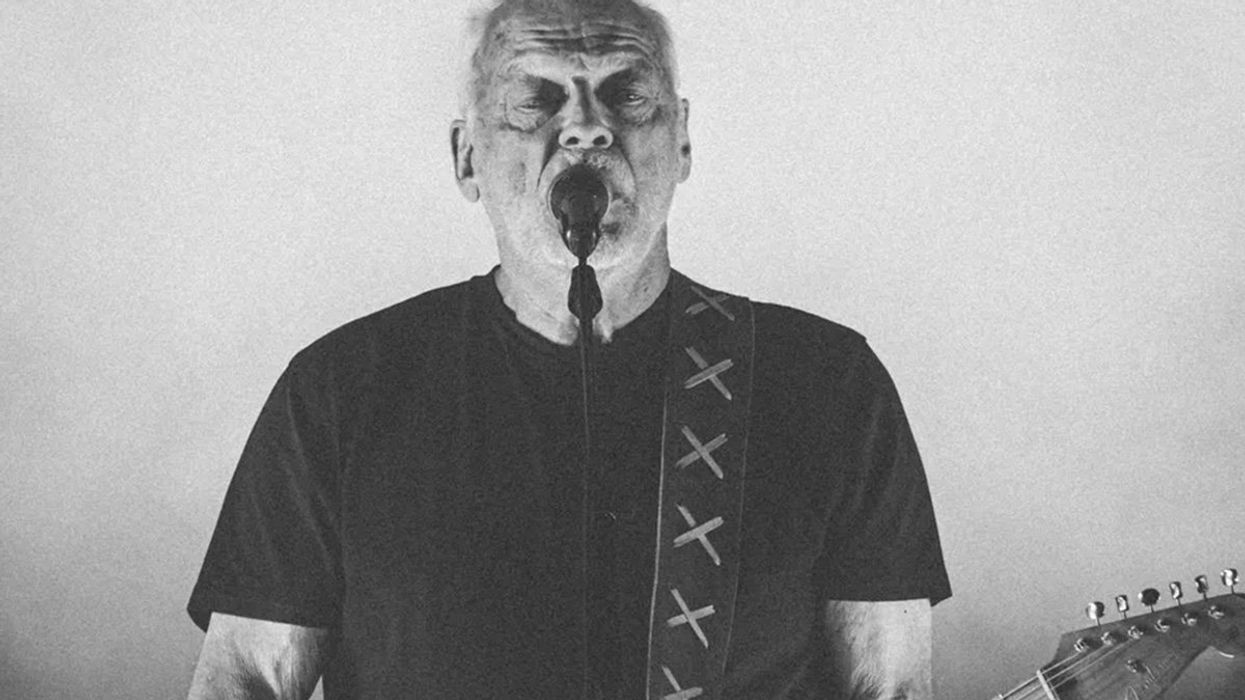

The patriarch was R.L. Burnside, who was born in 1926 and learned to play at the feet of his neighbor, Fred McDowell, who was the foundation of North Mississippi blues as most of us know it—although the style, with its intricate rhythmic bedrock, is really an offshoot of the straight-from-Africa sound of the fife-and-drum bands that are the precursor to rural acoustic and electric blues. My beloved friend and mentor R.L. died in 2005, but his sons, Duwayne and Garry, and his grandsons, Kent and Cedric, who collectively span two generations, carry on the family tradition. Cedric, in particular, who I met when he was a 14-year-old drummer supporting his “Big Daddy” on tour, has become a profoundly important part of his family’s musical legacy at age 44.

Quietly, without his grandfather knowing, Cedric was taking notes on the fabric of R.L.’s guitar style from his seat behind the drums. It was only on his deathbed that R.L. learned Cedric was preparing to step forward into history. “I had only really started playing guitar in 2002,” Cedric, who, along with Kinney Kimbrough, was already one of the two preeminent drummers in North Mississippi blues, recalls. “I was able to play for Big Daddy and show him a song I’d written, and—he couldn’t really talk clearly at the time—his eyes lit up, delighted. I could tell he was proud of me and he put his thumb up. He loved to throw that thumb up when he heard something he dug.”

Today, Cedric has been nominated for three traditional blues Grammys and took the prize for his 2021 album I Be Trying. He has also won a half-dozen Blues Music Awards and was awarded a 2021 National Heritage Fellowship by the National Endowment of the Arts, the federal government’s highest honor for folk and traditional arts.“I could tell he was proud of me and he put his thumb up. He loved to throw that thumb up when he heard something he dug.”

At a recent show at Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium, supporting his new album Hill Country Love, the simplicity and complexity of Cedric’s music was laid bare. With his guitar and singing supported by only a drummer—in the deep juke joint tradition—his playing echoed his grandfather and McDowell, but was also a self-created style of swift, sharp, fingerpicked, hard-chiseled melodies that resonate like the music’s deepest bones. At times Cedric sounds like Ali Farka Touré, an artist he had never heard until his own approach was entirely developed. And Cedric’s lyrics deal with the struggle of being Black in an oppressive culture, of fighting up from poverty, of finding his own way in a tradition that goes back more than a half-century in his family’s history and to a place two continents away.

As any of Johnny Cash’s children, or Duane Betts or Devon Allman, might tell you, hefting that kind of legacy to new ground can be a heavy load. And yet, Burnside relates, “I just try to let it flow and do what my heart tells me to do, and if it works, great. If not, I regroup and try again. But I am grateful for how far the hill country sound has come, and grateful I’ve been able to help carry it. I’m about letting people know where I got it from, while paving my own way. As long as I can help keep it alive and well, I’m honored to be able to do that.”

Along those lines, Cedric says he’s got enough new original songs on his phone for three or four more albums. “So, I’m just going to do my own thing and put out as much music as I can before the good Lord calls me home, and show as much of this music to the younger generation around hill country—maybe even my own kids—so after I’m gone we can keep this going.”

R.L. would be very proud.