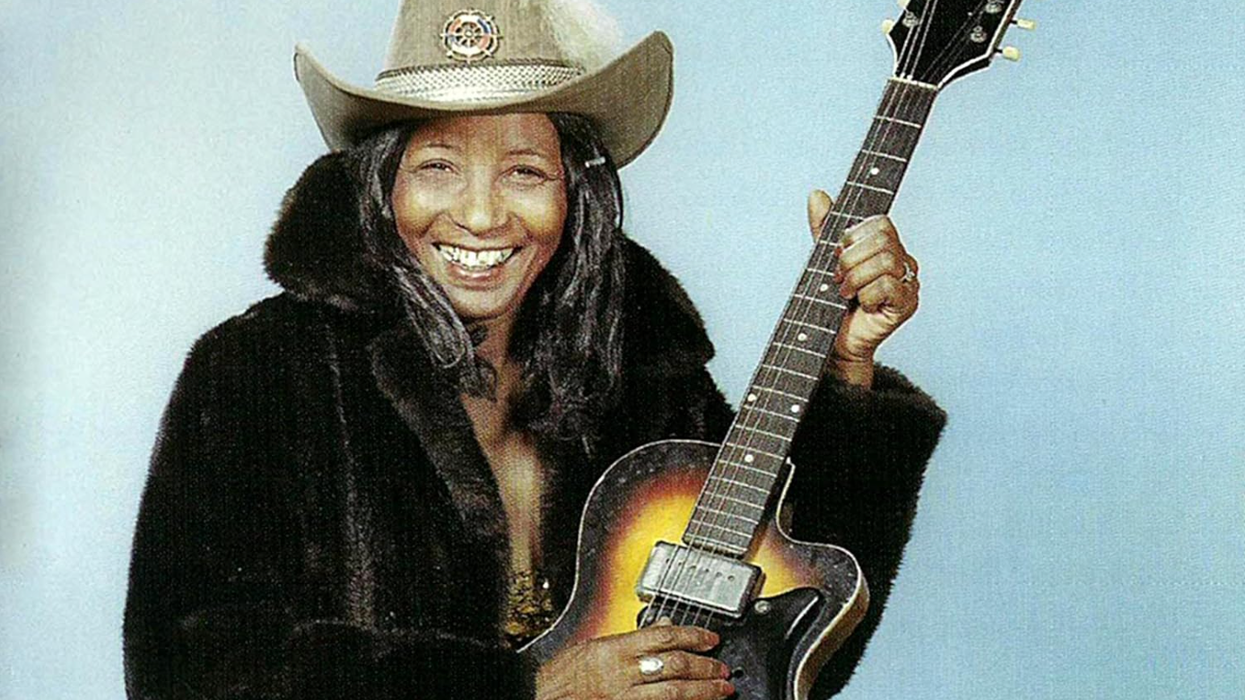

This is a story about a small act of kindness. It occurred in 1995 at a club gig, but the tale is rooted a dozen years earlier, when I started to develop my guitar playing in earnest. My bookend idols then were Roy Buchanan and Gang of Four guitarist Andy Gill—a roots and blues icon and a conflagrant punk-rock innovator. It might seem they had nothing in common, but listening reveals a shared love of taking risks, unpredictable turns in their playing, and a determination to push the envelopes of angularity and tone. Roy played a Tele and Andy had a Stratocaster, and when I initially took to stages, I had one of each.

I’d first heard Andy when Gang of Four’s blistering, brilliant 1979 debut album, Entertainment!, came out. Absolutely nothing sounded like Andy, with his piercing tone and atonal bombs, and his intention to screw with the conventional architecture of rock. Then there were the songs: salty, wise, withering social commentary in three-and-a-half-minute bursts. I instantly loved Gang of Four!

So, in 1995, during the run of my alternative-rock band, Vision Thing, I got a call from a Boston-area promoter—who I’d been begging for a gig, since he booked all the best joints in town—offering an opening slot for Gang of Four at a club called Axis. I was thrilled, but I was also conflicted, because I wanted us to be our best in front of my heroes and their audience, but Vision Thing was imploding, and that rarely makes for good work.

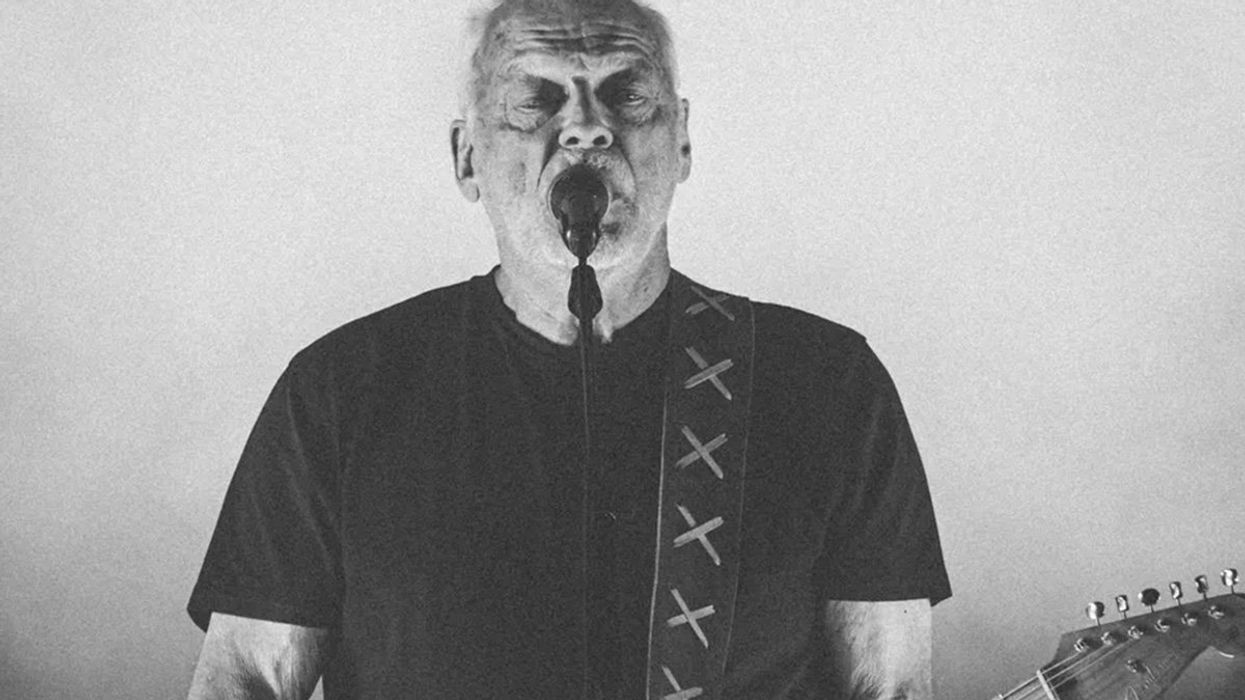

Moments later, in walks Andy Gill and Jon King, Gang of Four’s singer.

Maybe anyone who’s been in a band that’s a democracy can relate? As usual in such situations, everyone had a voice, but one person—me—did 90 percent of the work, including most of the songwriting. For months there had been constant arguments over direction, arrangements, gigs, attire, producers, the record label, and the beat goes on. Some members were fond of frequently proclaiming how much better they were than most of us, including me. Holding the band together for the cycle of our just-released album was exhausting and depressing, and I thought that perhaps after this “dream gig” with Gang of Four, I should just quit performing. Who needs the BS?

As it turned out, we were great on that gig—colorful, rocking, raw, emotional, and even inspired. But as soon as we got offstage, the rhythm section and Vision Thing’s other guitar player abruptly split without conversation, leaving the rest of us in our dressing room, feeling happy but awkward.

Moments later, in walks Andy Gill and Jon King, Gang of Four’s singer. They introduced themselves, thanked us for opening, and started talking about how much they liked our performance. When Andy complimented my tone and approach, I could barely stammer a “thank you.” And then, after perhaps five minutes, they split to get ready to annihilate the house.

I felt as if I’d been anointed. If Andy thought I was onto something, well, dammit, I was! Just a few words restored my belief in myself as an artist and buoyed me through that band until it died some months later. His simple act of kindness encouraged me to keep writing songs and playing, and to navigate a path that would take me to places like the original Knitting Factory and Bonnaroo, France’s Cognac Blues Passions and Switzerland’s Blue Rules, and 20 more years of clubs, festivals, theaters, and studios. Heck, maybe even to this gig.

In early 2019, while interviewing Andy for PG, I got to thank him for his kindness, and let him know he’d inspired me to continue making music. He was gracious, of course, although I’m sure he didn’t recall that night. For all I knew, he said that to every guitarist who ever played in a band that opened a Gang of Four show.

But that doesn’t matter. What matters is that he simply said it. And I try to carry that lesson with me today. If you like what another musician you see is doing, say it. And if you’re mezzo-mezzo, offer a compliment anyway—on gear, on a certain song, on a vocal inflection or a lick. Find something pleasant and encouraging to say, because you might be saving someone’s musical life. Also, this does not only apply to music. If somebody made you a great sandwich, compliment them. Hell, tell the bagger at your local grocery store that you appreciate them. It doesn’t cost anything, and can lift the spirits of that person.

When Andy died a year later, I was sad, but still grateful for his words, and grateful for a simple reminder that can be a buoy for yourself and others in the sometimes turbulent river of life: Be kind.