If you were a teenager in mid-’70s England, not a fan of corporate rock, and not ready for disco—you were in luck, because punk was about to hit. Bands like the Sex Pistols, the Clash, Sham 69, and many others challenged the establishment and redefined popular music. Their no-rules, anti-authority ethos was a rallying cry for people too young to be hippies and not interested in the Beatles.

But the early punk bands had limitations, too—the most obvious being their subpar chops. Attitude and bravado couldn’t mask the simplistic nature of their music and, in a sense, contradicted the ideals professed in their lyrics. That only got worse as punk evolved, and by decade’s end, punk, in England at least, was conventional, formulaic, and—worst of all—safe.

But that changed with the dawn of post-punk. The post punks, although disillusioned with the staid convention of punk, took punk’s ethos seriously. They were irreverent. They were audacious. And many of them also boasted superior technical skills, deep roots, and a daredevil approach to recording.

Mastering their instruments was a statement of sorts. “Post-punk, in general, was more of a reaction to [those limitations], where you actually have more advanced musicianship,” says Vivien Goldman, a prominent U.K. journalist, recording artist, and publicist for Bob Marley. Her critically acclaimed album, Resolutionary (Songs 1979-1982), was reissued last summer. “That’s what post-punk really meant: the thing that came after punk where people either weren’t capable of being that simple or they didn’t want to be. They had moved on,” she observes.

Post-punk drew from a deep pool of influences, too. Funk—especially ’70s Parliament-Funkadelic and early James Brown—and, in some cases, free jazz, made a big impact. But aside from punk itself, nothing was as influential as dub reggae.

“A big thing one should mention, maybe the most important thing, is dub and the impact dub had with making people eager to deconstruct the expected,” Goldman adds. “That remained very key for the whole post-punk aesthetic. It taught you to think in fragments, musically. That awareness—that your guitar could be split up into many different echoes of itself and then be brought back into itself… Having that implicit in your sound contributes to the guitar in post-punk searching for a new sound.”

And what a sound it was.

Post-punk guitar was an abrasive, natural distortion—usually produced without pedals—with the treble set to 10 and the bass at zero. It was gnarly. “That abrasiveness was part of the mandate in post-punk to do something different with your guitar,” Goldman says. “People became much more abstract.”

As a movement, post-punk didn’t last. It fizzled in the early ’80s. But its impact was enormous. Bands like U2, the Red Hot Chili Peppers, and the Minutemen list punk and post-punk bands as their primary and formative influences. Post-punk bands were many—some were huge and some obscure—and include Joy Division, Wire, the Birthday Party, the Fall, the Slits, the Flying Lizards, and others. For this feature, we focused on three guitar-centric outfits: Gang of Four, the Pop Group, and Public Image Ltd (PiL). We interviewed their primary axemen—Andy Gill, Gareth Sager, and Keith Levene—and got the details about their influences, guitars, amps, limited use of pedals, studio techniques, songwriting, and much more. Short of reading a book on the topic, consider this an in-depth primer on post-punk guitar.

Gill, in one of his typical onstage stances, has mainly played this Fender Strat Ultra from the ’80s in recent decades. It has been modified with a kill switch. Photo by Debi Del Grande

Gang of Four’s Andy Gill

Gang of Four, from Leeds, merged punk energy with a danceable groove and angular guitar noise. Andy Gill, the band’s guitarist, generated that noise with an assortment of guitars—detailed below—and a solid-state Carlsbro amp. Their message was angry, petulant, and yet—at least according to Vivien Goldman—lovable. “Most groups aren’t as clever with their lyrics as the Gang of Four,” she says. “They were more sophisticated. Nicely dressed boys, but poisonous with their sarcasm, you know? I love the Gang of Four.”What attracted you to the guitar?

Andy Gill: One of the things I liked was the physicality of the guitar itself. It’s this bit of wood with metal strips that go one way and metal strings that go the other way. You press the metal against the thing, but while you’re doing that, it makes incidental sounds. The scraping, the sound of the finger moving along the string, the sound of the pick against the string. All those scrapes and zips, all those things mixed in with a little bit of a tune made something quite magical. Right from the word “go,” I was interested in the rhythmic side of it. You could play a single note and make a kind of Morse code out of it in a very simple way. When I’m coming up with an idea for a song, say, my starting point is often a drum idea—a beat idea—that feels cool and exciting. You want that excitement and it might come from a drum idea and it might be a pulse on the guitar.

Those ideas are something you hear or something you would play percussively on the guitar?

Gill: When I was working with early Gang of Four, I might say to Hugo [Burnham], he was the drummer at the beginning, “I think the beat should go like this.” He’d play that and then we’d move things around. He’d get a little bit annoyed because I was telling him how to play drums, but those Gang of Four songs were making this sort of tapestry: “The high-hat goes over here, the kick drum goes there, the guitar does this in between.” It all fit together like that.

The band becomes like a single instrument, really. It’s not that more traditional approach, where you’ve got layers of things on top of each other. Gang of Four was not in that hierarchical pyramidal structure. On those rare occasions when someone makes the mistake of saying to me, “Oh Andy, play us a bit of a Gang of Four song on the guitar.” I go, “I could do, but it wouldn’t make any sense.” It doesn’t really stand up on its own. It functions within the structure of the other instruments being there.

Were those interlocking parts very deliberate and worked out? You didn’t jam.

Gill: Me and [lead singer] Jon King were very contemptuous of jamming. We’d say the word “jamming” as if it was a dirty word. For some reason, we felt the idea had to be pre-formed and that all we were doing was putting it into physical existence.

Was dub reggae a big influence on your music?

Gill: It was in the air. When I was a teenager, there were people who knew about reggae. They were a tiny minority—most people didn’t have a clue about what it was. There were people who had heard early Bob Marley, like Soul Rebels, and I guess Catch a Fire was the first big record. But me and some of my friends were into that ska reggae—the slightly faster, pre-dub stuff.

Like the Skatalites and those types of bands?

Gill: That kind of thing. Dave and Ansell Collins, Desmond Dekker, and Jimmy Cliff. I mean, dub reggae is essentially that, but a bit more stoned and a bit more slowed down. That earlier stuff, the ska stuff, was a bit more upbeat. It was the antithesis of prog rock. It was not like European and American pop. It was so much more about feel and groove. Melodically it was usually really simple.

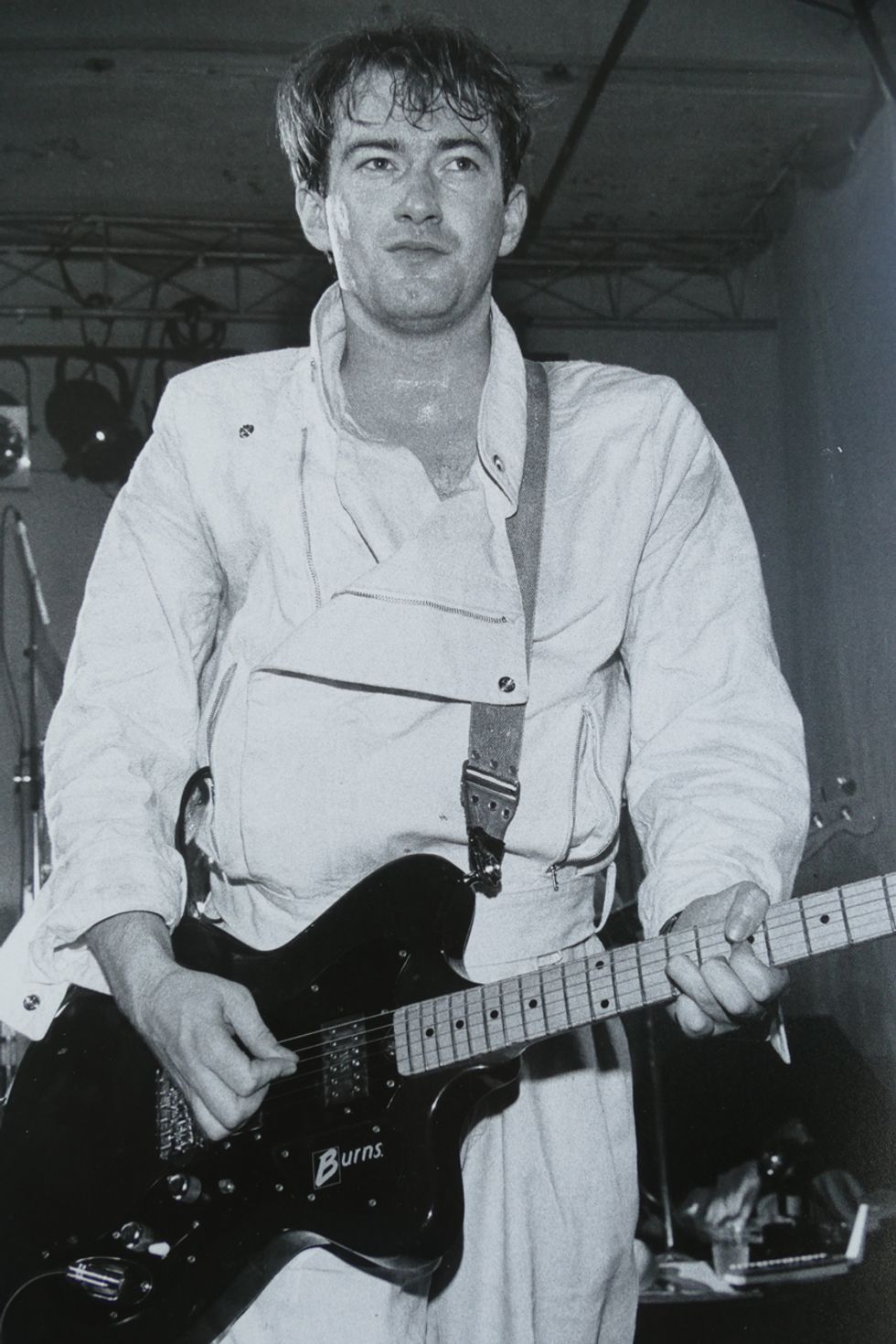

Gang of Four guitarist Andy Gill stalks the stage of Providence, Rhode Island’s Living Room in 1982, a Burns guitar in hand. “The scraping, the sound of the finger moving along the string, the sound of the pick against the string,” he says, “made something quite magical.” Photo by Paul Robicheau

But I think the main thing about early dub recordings was instruments dropping out. For example, the drums, bass, and guitar are all playing and then the guitar and bass drop out and it’s just the drums—and it’s that lovely spacious feel. After maybe 16 bars the bass comes back in and that’s a great feel. Then the guitar comes back in. The instruments take turns dropping out. I used to call that an “anti-solo.”

Gang of Four did exactly that. The guitar would drop out and it would just be the bass and drums, or the guitar and bass would drop out and it would just be the drums, and then vocals would do something over the top. That would come to a climax and then the bass and guitar would come back in, which is something very much from dub reggae. It’s from the early studio work in Jamaica where whoever was producing or mixing it would say, “Let’s stick a load of tape delay on the vocal and drop out the drums.” But then people learned to play like that. Gang of Four certainly learned to use that thing as very central.

Funk was in the air at that time as well.

Gill: Yeah. We all got quite obsessed with Funkadelic’s One Nation Under a Groove. But way before that, it was James Brown. His rhythm section was so tight. I always pictured it like a metal bridge with crossbars—if you think of those early 20th century railroad bridges, which is just a series of squares with diagonals across them—it was so rigid and tight. But then you’ve got James Brown and sometimes he’s tight with the structure and sometimes he’s breaking the structure down. He’s like something smeared over the tightness of the rest of it, which is something I’ve always loved as an idea. That’s something that happens in Gang of Four. Because I was very obsessed with the bass and drums being super tight, super metronomic, and the guitar would sometimes go along with that and reinforce that structure, and sometimes it would work to destroy it—either with feedback or with beats that were just so off. The off-ness of the beats demonstrated how rigid the structure was. You could reinforce it or you could try to destroy it, but either way, it drew attention to the groove.

They call post-punk “punk,” but when you compare it to, say, the Sex Pistols or the Ramones, it’s so different.

Gill: You think of guitar playing in classic punk and it’s basically metal chords—it’s just hammering out the chords, isn’t it? Not that there is anything wrong with that. It sounds like I’m being critical of that, but it’s very different. I think when punk came along, when suddenly in the U.K. it took over—I guess in late ’76, early ’77—suddenly it was everywhere. Lots of people were really upset about it. Everybody was having arguments about, “What is musicianship?” There would be old conservatives going, “This isn’t really music.” It became a fascinating argument, and people getting banned from shops, and television not knowing what it could say and what it couldn’t say, and everything was up for question. I think that was the exciting thing about punk. Musically, the instrumental things weren’t particularly radical, but it was getting to hear Johnny Rotten on the radio sneering over these tracks at the pomposity of all the old guard. I think the big takeaway from that was—especially the Sex Pistols and Malcolm McLaren—they took down a lot of the barriers and made it obvious that anything was up for grabs. You didn’t have to write a love song. You could do what the hell you liked.

A lot of your songs stay on one chord, similar to funk.

Gill: Exactly. I was listening to some dance music earlier today and it made me think about “To Hell with Poverty,” where the guitar essentially goes between A and C. There’s no chord. It just goes between the notes A and C. There is one section in the middle, which is basically E. It couldn’t be simpler. It’s a great groove. It’s four-on-the-floor—it’s like mutant disco—and the great bass riff, and the guitar wailing on those notes on top. The vocal does a lot of the work. It’s creating a lot of excitement and tension. If you try and fancy it up with some other notes, you lose that intensity.

YouTube It

Check out Gill’s gold Strat-style guitar (sans neck pickup) in this live 1981 version of “To Hell with Poverty.” Also note his abrasive, fingernails-on-the-blackboard tone. “A guy called Johnson made these Strat copies,” Gill says. “I liked it and I used it.” Despite his hard attack, Gill notes: “The strings I like are the Hybrid Slinky. The top one is a thin .009 but the bottom ones are maybe .048? Maybe. Ernie Ball makes these ones with heavier lower strings and thinner top strings, which I like.”

How did you generate your tone?

Gill: On the first album, I didn’t use any pedals at all. There is a make of amps called Carlsbro. I don’t think they are known in America, but they were transistor amps. People were very sneering about transistor amps back then. People would say, “You’ve got to have a valve amp. It’s a much better tone. It’s much warmer.” I’d say, “I don’t necessarily want the warm tone. I want a sharp, abrasive tone and I think this transistor stuff does it.” The first one I was using was called a Stingray. You just turned the treble up full. I had it pretty loud, so the guitar was sometimes on the edge of feeding back.

With the second album, I did start using a lot of tremolo and vibrato, which I hadn’t done before. That was in the amp. I don’t think I was using pedals on the second album, either. I still have this amp and I still like it. I often use it live as part of a pair. The Carlsbro does have a great sound, but I’m not sure about the amps they make now. The one I’ve got is from 1980. It’s got built-in tremolo, vibrato, and, I think, chorus as well. I was very doubtful about effects on the first album, but because they came with the amp on the second album, I started playing around with it and found that quite interesting things could be had.

One of the big things that distinguishes post-punk from American hardcore is that many of you were signed to major labels. Why is that?

Gill: Some labels probably felt they missed out on punk—that they weren’t quick enough to see the commercial side of that. It was a time when a magazine like the NME was very influential. People were talking politics, aesthetics, philosophy, and it was a bit like a movement had been let loose. It had many different facets and manifestations. Whether it was Killing Joke, the Slits, the Raincoats, Gang of Four, or Joy Division. They’re all different from each other, but all quite exciting ideas, and that’s what people were into for a while. That was an exciting time and the record companies wanted to get in on that.

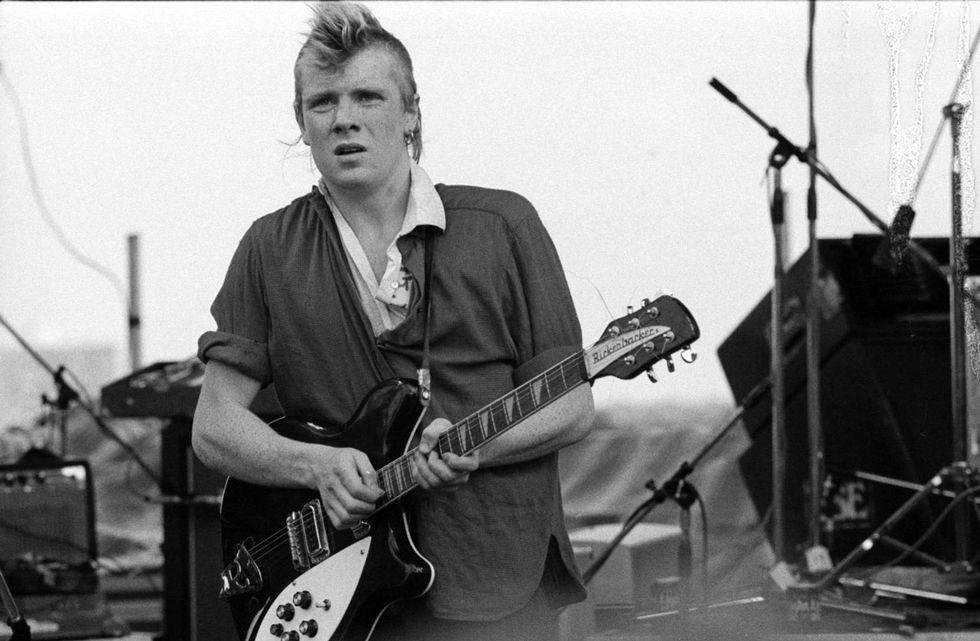

Prickly single-coil pickups have been an essential element in the post-punk guitar sound. Although he started the band with a Rickenbacker, the Pop Group guitarist Gareth Sager plays a Fender Jazzmaster, among other instruments, today.

Photo by Jordi Vidal

The Pop Group’s Gareth Sager

The Pop Group, from Bristol, were punk, funk, and not afraid of the avant-garde. Their first album, Y, was released in 1979, and time hasn’t mellowed its vibe. It’s still a jarring, dissonant, glorious mess and a fantastic showcase for guitarist Gareth Sager’s self-described “rhythm racket.” Sager uses an assortment of guitars—although in the early years his guitar of choice was a Rickenbacker—but, as he discusses below, the actual instrument is immaterial. (In fact, he’s recently recorded a solo piano album at Abbey Road, for October release.) Sager’s credo is, your tone’s in your fingers.What’s your background?

Gareth Sager: I was taught piano from about 5, so I had a pretty strong—being able to read the dots—musical background. I was at quite an advanced music school, so I did learn about Stockhausen and John Cage and people like that when I was about 14 or 15. We used to listen to Tonto’s Expanding Head Band and things like that in music class. Unbeknownst to me, that was all really useful later.

But I was like most kids in Britain. I heard music on the radio and I read the NME and Melody Maker. There was a little gang of us that went to all the gigs that came to town. I saw Rod Stewart and the Faces when I was 11. That was a good start. Believe it or not, I had a few clarinet lessons, but in the interim, everybody I knew was picking up guitar—this is the early ’70s—but I never did. There was a Spanish guitar in my house. You know those—the action was so high I thought it was physically impossible to play. But slowly I got more into it. Then when punk happened in 1976, this band called the Cortinas—it was formed by guys from the school I went to and the school [Pop Group vocalist] Mark Stewart went to—got pretty successful very quickly and they were playing the Roxy club, which was the premier punk club up in London. I’d go up and watch that and it was that classic case of punk that if your mates can do it, then you think you can do it as well. The very first guitar I bought was a Burns, and the body was so small that the machine heads weighed it down, so you would have to lift it up with your left hand [laughs].

Were Burns guitars cheap and easy to find?

Sager: It was really cheap. It was £60. And even at that I had to borrow the money off some girl to buy it [laughs]. I’ve still got it, actually. It literally looks like a palm tree with a bit of fencing on it.

Some people you’ll talk to, all they talk about is guitar players they love. I just loved music, really. I loved what bands sounded like and that sort of thing. Probably the first real guitar player [to interest me] was Wilko Johnson from Dr. Feelgood. His uniqueness of what he did with the guitar just knocked me sideways. I mean, I didn’t know anything about the guitar. He just seemed to make a different sound out of it from what everybody else was doing at the time. He’s become a very good friend since, so that’s quite interesting to be able to tell him. He had no idea what a big influence he was until about 20 years ago. He influenced all of the punk players for certain.

Before we had the Pop Group, all the people I hung out with really loved funk. The super heavy funk was coming in then, whether it was the Ohio Players, the Fatback Band, or early Kool & the Gang before they went sort of mellow.

Were those funk groups coming over to England?

Sager: I saw Parliament-Funkadelic in 1978, when we were making the first Pop Group album. That was the Mothership Connection tour, which was absolutely fantastic and they were absolutely wild. I saw all the first lot of punk bands, too: the Clash, and Subway Sect were a really important band. They had a really unique guitar sound. They were much more anti rock ’n’ roll than the Pistols or the Clash or anything. They didn’t wear their guitars between their legs. They had them really high up. They played really minimal chords. Seemed to be their only reference point was White Light/White Heat by the Velvet Underground. They were really fantastic and they had no interest in being glamorous or anything like that. They had this incredible rough style of playing guitar, and I took to that. Other influences would most definitely be Television’s “Little Johnny Jewel” and the first Richard Hell and the Voidoids album, Blank Generation—Robert Quine’s playing on it. But the real thing about me, as opposed to any other guitarist you’ll talk to, is I never learned anybody else’s music. I never learned a Beatles’ song or anything.

You can hear that funk influence in your playing. Did you spend time developing those chops?

Sager: There are two guitars in the Pop Group, and John Waddington, the other guitarist—he hasn’t stayed in the music business as long as me—had a much purer funk thing than me. Mine is much more fucked-up funk, whereas he’s playing very much as near as you can to Chic or something. It’s a mix of the two of us and I can’t take credit for stuff he’s done. People might think it’s me, but no, it’s him.

My thing was to have this, “rhythmic racket.” It was important to me that there were no rules. The whole concept to me was to use anything you can to be the most effective you can when it’s possible.

Some of the classical composers you mentioned did that.

Sager: Oh, 100 percent. There’s nothing new. I just developed my own individual voice. It’s no better than anybody else. It’s just me and you can hear when I’m playing it. The conceptual stuff I got from John Cage was enormous. That really was the thing that allowed me to ask something like, “What’s wrong with hitting the guitar with a bottle?” All noise can be created into music if it’s arranged in whatever way you feel possible.

Gareth Sager plays with the Pop Group at Alexandra Palace in 1980, one year after the band’s debut album, Y, was released. “We did our first album with Dennis Bovell, who was the only really true British dub master,” says Sager.

Photo by Paul Roberts

That’s interesting, because the first wave of punk definitely owed a big debt to old time rock ’n’ roll.

Sager: When I heard the first Sex Pistols’ single “Anarchy in the U.K.,” it literally sounded like Hawkwind and I was so disappointed. I’d heard these things from New York, like Television, the first Patti Smith single, “Piss Factory.” [Editor’s note: It’s the B-side. The A-side is “Hey Joe.”] They had something really experimental, something really interesting, a whole new angle, like a whole new world, really. And then the British stuff, obviously, was incredibly influenced by the Ramones, but as Steve Jones says, really they wanted to sound like the Faces. Glen Matlock, the original bass player from the Sex Pistols, plays in the Faces now. What inspired the Pop Group, and me in particular, was that the first lot of punk rock was, “Go out and do your own thing,” but then became incredibly formulaic, which seemed worse than what was there before really.

Talk about your tone. What gear did you use?

Sager: I had a hollow Rickenbacker, about 1971. What’s unbelievable is I can’t remember what amp I was playing.But that brings me back to my real point: It was always important that whatever guitar you played through whatever amp, you could sound like yourself. You didn’t panic if you didn’t have the right amp or you didn’t have the right guitar. You were still able to sound like yourself.

Are you saying the essence of your tone is really in your fingers?

Sager: It is really in my fingers. In the fingers, and probably for the Pop Group the one little X-factor was that I always used a triangular bass plectrum.

How about chords. You weren’t playing power chords. How did you come up with your voicings?

Sager: I just made them up. I’d never looked at a chord book or anything like that. There is a lot of dissonance from early Pop Group stuff.

But you had a music background. You knew what you were doing.

Sager: Of course, I had the background. I understood you can play a 13th with a second there. People have got to tune their ears into it. It’s not the Beatles.

Using that dissonance as well as a lot of feedback created a lot of interesting sounds.

Sager: In lots of ways, I would love to get back to that. I’ve tried as much as I can to keep that naïveté in every record I’ve done. That is the real beauty of music. It brings a freshness to stuff, where you’re not dependent on the rules. Obviously, I do appreciate great harmony and stuff like that. Down the years, I’ve got more interested in that area, to be honest. I was probably going very much against that in the early Pop Group stuff. But you have to develop as you get older. There’s nothing worse than these awful people that are still playing what they played in 1981 or something.

YouTube It

Sure, they’re lip-synching, but decent live footage of the Pop Group at their inception is impossible to find—and this performance of “Where There’s a Will” is every bit as anarchic as their fractured funk/dub sound.

Were you were consciously working to obliterate the standard song form?

Sager: The great thing was we really didn’t know how to write songs. I knew how to write classical music. You’ll find lots of our stuff is in funny 16-bar patterns that I’d written classical music in and not adhering to what a pop song was meant to be about. I didn’t know what a middle eight was—that sort of thing. I just knew you have another bit here and then you put another bit there. Invariably we’d start with a chorus as well, which is a quite amusing thing about the Pop Group. The good thing is that on lots of the early stuff, we would be like blues players and we’d change on the 7th bar or the 5th bar instead of making it all 8s and 12s and 16s and all that. That is a very simple thing to do that throws music straight away.

How did you communicate that with each other?

Sager: Because we didn’t know any better, we just felt where it changed. We learned it together so we all changed at the same spot. But that was quite funny when we came back to learn the stuff again when we reformed. When we were counting out we’d go, “Shit, it changes on the 9th,” which made the drummer very annoyed.

Did the band improvise as well?

Sager: You had a solid song structure, but over the top of it you had somebody like myself who was just improvising and never doing the same thing twice.

Other bands, like Joy Division or Gang of Four, were more song focused.

Sager: They were more traditional rock. I think Joy Division took a great deal from the very early Pop Group. We had a song called “Colour Blind,” some early demos, but we moved on from that. To their credit, Joy Division picked it up and made a success out of it. But because we were so into black music, we just wanted to show our influences from reggae and funk and everything as well. So as soon as we could, we would “play on the one,” or what we thought was the one [laughs].

How big an influence was dub?

Sager: Bristol has a very big West Indian community, so we heard dub pretty early on. Particularly our lead singer, Mark Stewart, he was a really proper big dub fan from a very early age. The minute I heard any Lee “Scratch” Perry or that Super Ape album … you have no idea how these things are being done, so it sounds like a magical entrance to a new universe.

We did our first album with Dennis Bovell, who was the only really true British dub master. Straight away, I was learning from the only master around. That’s how I started, with a guy like that at 18 years old. It was making the whole mixing desk feedback on itself and dubbing it up, so that was normal for me.

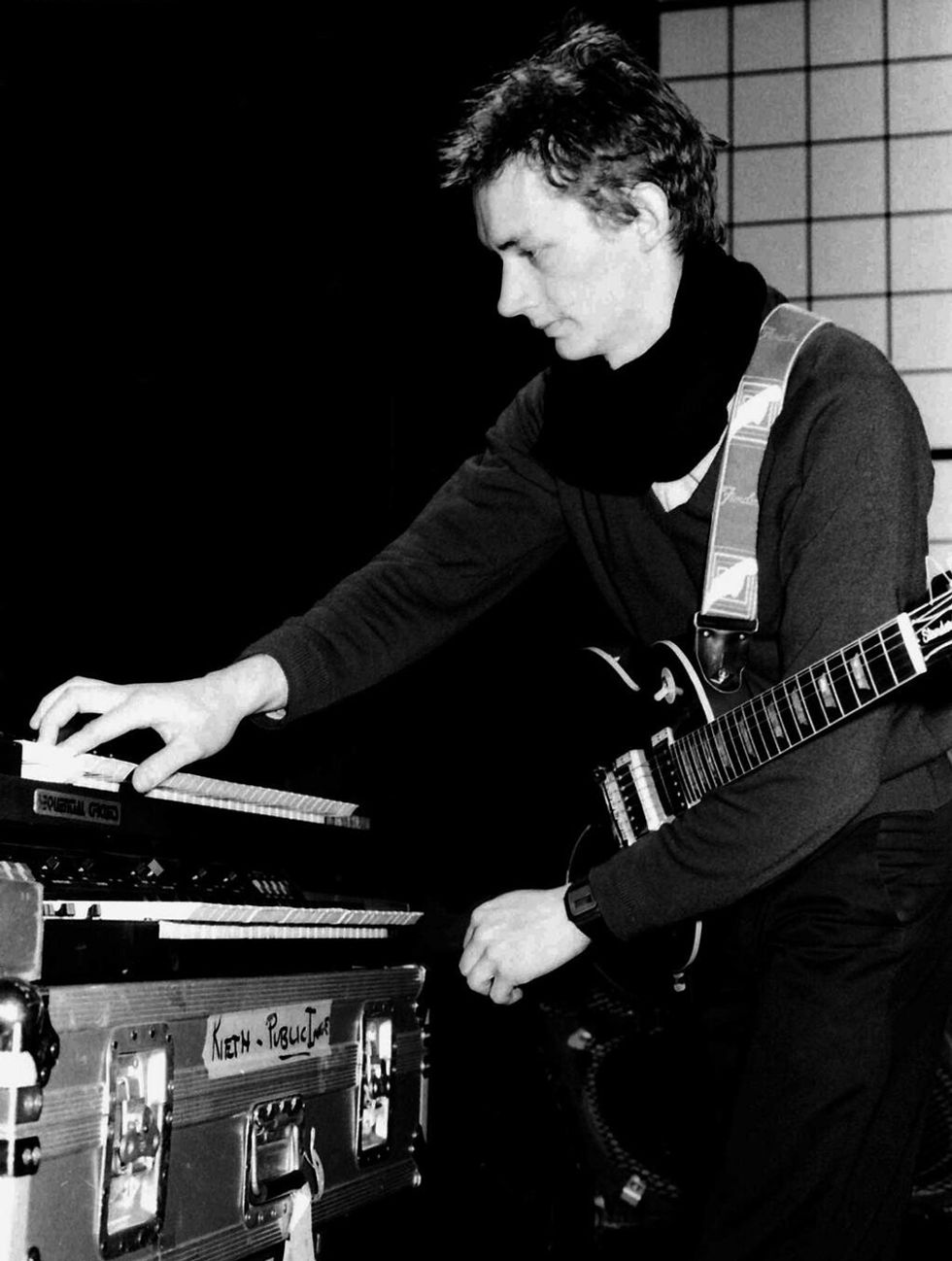

With Public Image Ltd, Keith Levene was the primary musical driver behind the group’s expansive, dissonant, and experimental sound. He found a perfect, dub-informed instrumental foil in bassist Jah Wobble. Image courtesy of Keith Levene

Public Image Ltd’s Keith Levene

Public Image Ltd, founded in 1978, was heralded as John Lydon’s—aka Johnny Rotten’s—follow up to the Sex Pistols. But that somewhat misses the point. PiL wasn’t another punk band. They didn’t write songs per se—not in the traditional sense. They obliterated the traditional verse/chorus formula and lived on the musical fringes. Their sound was expansive, dissonant, and experimental. They composed music in real time. They sometimes failed, but that just made their successes sweeter. “My playing is just like it was in PiL,” guitarist Keith Levene says about his current style. “It’s just as electric. It’s sort of angry, and like toothpaste or crackly bright lights.”I read somewhere that you started as a roadie for Yes?

Keith Levene: I was a roadie for Yes, but I didn’t start as a roadie for Yes. I went to five shows in a row at the Rainbow and, in my secret self, I had this plan: I am going to work for Yes. By the time the fifth concert had ended—I don’t even know how because everyone was out of the Rainbow by then—I migrated onto the stage. I had a lot of experience since I was about 11 when I started helping bands and then youth clubs. I knew about Eddy Offord [producer/engineer]. I knew about Mike Tait [tour manager for Yes]. I knew what a mixing desk was. I was 15, nearly 16, and I got the tour. It was the Tales from Topographic Oceans tour. I did the English one. I was probably the lowest kid on the totem pole, but I was in heaven, man. I’m playing with Rick Wakeman’s synthesizers. I’m watching Steve Howe—who just so happened to be my favorite guitarist—with my favorite band. What more could I have wanted? And I came back with money.

Were you already playing guitar at that point?

Levene: Not really. When I came back from Yes, I realized the thing I missed that was right under my nose: I didn’t like bands. I wanted to be in a band really badly. So, I suddenly had this mission: I’m going to get a Gibson and I’m going to really play hard. I had this SG copy and I was just dicking around badly. I found a guitar-playing buddy that was older than me in the neighborhood and that really helped. I learned how to learn things off records. I played the guitar a lot. After Yes, it took me about seven months to get a Gibson Les Paul Deluxe.

The next thing I knew, I was in the West London scene working with Bernard [Rhodes, manager] and Mick Jones and putting the Clash together. It was pretty quick. I wanted to be in a band and it was a good time to be in a band. I didn’t want to be Marc Bolan—I didn’t want to be anybody and that had all been done. The Beatles had all been done. That’s why Public Image endeavored to be the way it could be when it was at its best—because of all that history, all those experiences of a new kind of freedom for the first time.

You don’t play blues scales or power chords. How did you develop your style?

Levene: Everyone wanted to be either Duane Allman or Jimi Hendrix or so-and-so. The message I got from that was, “Anyone can play like someone else.” I didn’t want to play like someone else. I loved guitar. I didn’t realize at the time, because I was so young, but I had quite a good command of the production of music. I didn’t realize that I was hearing in my head the end product of something. It didn’t mean I knew how to play it. It just meant I knew where the feeling was to click into it. I did practice a lot, but just simple, normal stuff that you have to practice to be good at guitar. Everyone can play guitar, but to be good at guitar is one thing. As far as I’m concerned, I’m not good enough even now. I’m playing a lot right now. I’m going through a practicing corridor, playing minimum five hours a day. That’s a lot of fucking guitar, man.

What did you learn from reggae?

Levene: When we’re talking about reggae, we’re talking about reggae that is the singles, when they had a lot of Jamaican singles—not even 12-inches, but 7-inch singles. There would always be a great commercial record and on the other side would be an instrumental. That’s what evolved into the DJs talking over the instrumentals, and they’d be toasters, and then they put effects on it—and then in the studio they started dubbing out the backing tracks. That’s why a lot of reggae tunes you hear actually all got the same backing tracks—Allah, Aston “the Family Man” Barrett, Horsemouth on drums … you can go on and on. But the thing is, reggae singles evolving into this dub. As I was listening to prog rock and drifting through working for Yes and thinking, “I really want to do this thing”—that was my soundscape. I made a point of finding out how they did it in the studio and I’d think about it all the time. I mean, we’d sit around in squats—me, Sid Vicious, and a couple of other people—and the room would be empty and we’d be making the rhythms with our mouths. The whole Jamaican 12-inch scene was hand-in-hand with what they call the punk scene—or the scene I was on, the West London scene.

Although he started with Gibsons, part of Levene’s signature hard, clangorous, PiL-era sound was within the guitars he came to favor: Travis Bean Artist and Delta Wing models with aluminum necks, and an all-aluminum Velano T-style. Levene favors a thumbpick or nothing, and uses .013–.056 strings.

And you applied that knowledge when you started recording?

Levene: The thing that really kicked me off was Bill Price, the producer with PiL on the first single. It was done at Wessex Studios and he was such a fucking cool guy. He was a really good producer and I learned so much from just recording that single. That led to recording the first PiL album, and we were quite audacious, quite cheeky and we were saying, “We only want it our way. We’re going to produce it. We’re going to write it. And we’re not even going to know what it is when we walk in there.”

That was another thing I used: to real-time compose the PiL stuff. [Bassist Jah] Wobble was fantastic at that. Wobble made it really easy to do that because he hadn’t played in other bands, so he wasn’t marred by having worked with other musicians who were very pedantic and want to know what key it’s in and this and that. With Wobble I could just say, “Do the line you’re doing but just move it down one”—because it might’ve been in an awkward place for the guitar. It would be perfect. Wobble would play shapes and Wobble—he’s definitely the best white-guy dub bass player there is. It’s that simple. He’s the Aston “the Family Man” Barrett of white people.

How is real-time composing different from improvising or jamming?

Levene: People are running around improvising with pockets of chops, but they’re not taking any chances. My thing was, “I don’t even know what the tune is.” Maybe a beat is going and I put my hand up, which means, “Put the fucking red button on.” The rule was, “Don’t turn the red [record] button off, don’t do anything. Talk to us in the middle, but don’t turn the machine off until we say.” For “Swan Lake” [off 1979’s Metal Box]—I had the idea and I just played it because I got it off first time. “Poptones,” most of it I made up on the spot. Sometimes we’d play it back and redo it. That was part of PiL—sort of failing in public, as well as doing really interesting things. That’s the Metal Box. The reason it’s so expansive is it takes you into areas of failure and areas that you just wouldn’t normally go into. And a lot of people really liked it.

Would you do editing after the fact? Did you compose by way of editing?

Levene: Okay, here’s a great example. There’s a tune called “Memories” on Metal Box. We used the first section of one completely different mix and the second one of another. We had them on 1/4" tape by then, and I said, “Let’s edit the quarter-inches and see what happens.” And it worked. When you hear it now, you’ll know what happened.

You had a lot of unusual guitars—Travis Bean, metal-neck guitars—how did you come upon those?

Levene: I originally had a Les Paul Deluxe. Then I had this Mosrite, which I wish I kept. Then I had a Les Paul Special, which was doing fine for me. Then when I got signed, I got a few really good guitars. One was called a Veleno and it was an all-aluminum guitar—that was the original metal guitar. It looks like an aluminum Telecaster. I had a couple of those and then, because I could, instead of getting another Gibson or this or that, I got this new thing: a Travis Bean Artist. They were really fucking individual. It was an amazing guitar.

YouTube It

Post-punk guitar wasn’t all fire and fury. In this live version of “Poptones,” Keith Levene’s chiming single-note pattern—played on his Travis Bean Delta—creates a hypnotic effect under John Lydon’s (surprisingly) gently intoned vocals.

One day I was on Denmark Street buying some strings, and I asked, “What’s in that flight case?”—because it looked like a coffin. I thought it was going to be one of those godforsaken Flying Vs. I can’t stand Flying Vs. And I opened it and it was a fucking Travis Bean Delta. This spaceship triangular thing with a metal neck just like my other one. I asked, “Is that for sale?” And they said, “Yeah.” And I said, “I want that and I want that amp to match it.” There was a metal amp that was a flight case all in one. It was a cube. I never used big stacks. I never needed to. I didn’t like them and it was a statement, I guess. Travis Beans were definitely playing into the sound I wanted: that glass-shattering-loads-of-notes-equals-one note. I don’t do conventional lead solos, but I do use really high notes and a lot of them that can be very fast and that can be a repeated pattern. Aside from that, I used a Fender Twin Reverb silverface with a master volume.

Did you use pedals?

Levene: I don’t like effects. When I record, I count using effects as production. I like the sound the guitar gets through an amp with nothing in between.

Your distortion was always from your amp?

Levene: Yeah. A lot of the time it was the Twin Reverb silverface, but no reverb. I hate reverb. I had the guitar plugged straight in, but if it’s the lead bit of the “Public Image” tune or “Poptones,” I had a thing called an Electric Mistress on the side for that. I’d have a direct and I’d have the [Electro-Harmonix] Electric Mistress. I was quite pedantic about it. But then I stopped using that and, invariably, if I plug in onstage, I plug it straight into the amp because live’s live.

When I see bands now—punk bands, bands that are trying to be serious—the amount of equipment they have on these fucking pedalboards and all this stuff. I get it. But I say keep it in the bedroom, keep it in the studio, and do the best aggregate of it. I normally do it all as I record. I call it sound-at-source. If I’ve got an acoustic sound and maybe it’s got a delay on it and what-have-you, that’s the sound it’s making and that’s the sound I’m going to record. I’m not the kind of person that starts going, “Doo doo doo doo doo,” while this fucking loop goes around. I don’t do any of that bullocks.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)