Chops: Beginner

Theory: Beginner

Lesson Overview:

• Learn how to visualize chord shapes over the entire fretboard.

• Connect triad shapes in a more melodic way.

• Develop a better sense of phrasing by simplifying your note choices.

Click here to download a printable PDF of this lesson's notation.

Dear 6-String Sensei:

I’ve read that to improvise in different positions on the neck, I need to learn about modes. But every time I sit down to work on scales, I get overwhelmed. Is there a bite-sized way to start with improvisation?

Thanks,

Eric D. in New York

Dear Eric,

Great question! There are probably as many answers to this as there are guitar solos on ’70s rock albums. Almost every guitar teacher has a favorite way to go about “cracking” the modes, but I’ve found over the years that it’s pretty easy to jump the gun on this one. This is because we are talking about something much deeper than simply rattling off a few scales from memory. We’re talking about learning the fretboard in terms of chord shapes, or intervals.

First, a piece of advice: One of the biggest deterrents to emerging guitarists is the idea that when we practice, we sit down to get better at music. This idea can be a pretty daunting task—so daunting, in fact, that it might be difficult to see where to begin. Sure, there are guitarists out there who are better than we are, and there always will be. But how did they get there?

This is something you’ll hear from me over and over again: The true reward of practicing is in the practice itself. In other words, don’t shortchange yourself by skipping steps to get ahead. After all, who is ever ahead of anyone in music, really? One mistake that many intermediate players make is to assume the practice of music is something linear. To begin working with modes, one might imagine it necessary to master the first mode, and then move onto the second, and then the third. Personally, in my decades of study, I haven’t had much success with this approach.

When pondering how guitarists actually improve at the instrument, I like to think less about a straight line and more about the idea of Russian dolls. If you unpack the largest in a set of dolls, there is a slightly smaller one inside. This smaller doll contains an even smaller one, and so on. My secret to mastering complex information has been to find the smallest manageable nugget of information and milk it for all its worth, trusting that this will lead to larger and more complex nuggets. It’s like working with Russian dolls in reverse.

This slight change in perspective can help point you toward a more accessible path for understanding the modes. Finding the right inroad will help you to master the modes when you’re ready. It will also keep you from overwhelming yourself and giving up, which is a major pitfall for most guitarists when they make early attempts to understand the fretboard.

Let’s look for a moment at a harmonized major scale, which is the basis for the modes. Let’s use the key of C, so we don’t have to deal with sharps and flats. In the key of C, we have the following diatonic triads (3-note chords):

C Dm Em F G Am Bdim

You may know that these diatonic triads can also be expanded into seventh chords. If you add the seventh to each chord, thus making it a 4-note voicing, here’s what they become:

Cmaj7 Dm7 Em7 Fmaj7 G7 Am7 Bmin7b5

However, if these chord shapes are unfamiliar to you at this point, it’s still possible to work on your improvising without digging all the way into the modes. There are many guitarists who struggle to sound authentic because the tools they use for improvising rely on the 7. But it doesn’t have to be that way: Many genres of music entirely avoid seventh chords, and even progressions based on seventh chords can be reduced to triads. So regardless of experience or skill, it’s useful for all players to learn to work with triads.

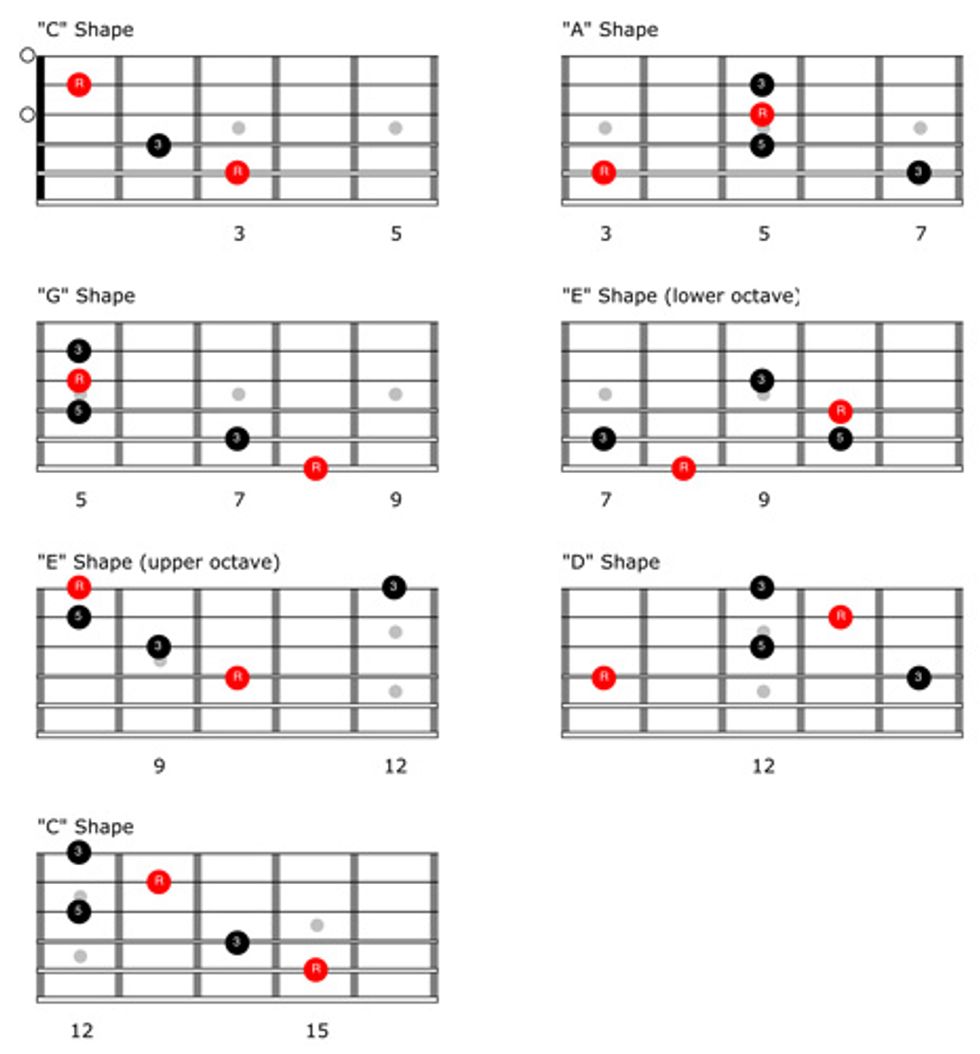

An easy way to begin to improvise in multiple positions is to locate each triad in different places up and down the neck. If you are familiar with the CAGED system, you’ll recognize some of these shapes.

This is useful for us as rhythm guitarists, but can it help us to play lead? Absolutely. But first we must chunk these chords down into smaller bits—their arpeggios. Then, we must learn to connect these arpeggios so we can move from one position to the next. For our purposes, the useful bits of the “G” shape arpeggio are covered by the “A” shape.

In Ex. 2 you can see a short melodic phrase that moves from the “A” shape to the “E” shape in the key of C. Also, don’t be afraid to add in some melodic notes that sit outside of the triad.

Click here for Ex. 2

For Ex. 3, we’ve connected the “D” and “E” shapes with a slide from the G at the 12th fret of the 3rd string down to F. As I mentioned before, focus on small ways to connect these shapes.

Click here for Ex. 3

We connect the “E” shape to the “D” shape in Ex. 4. It begins by outlining a Dm triad before moving up to 12th position and descending through a C triad (with an added F).

Click here for Ex. 4

In Ex. 5, we can see how to move from the “E” form to the “A” form. You can also think about this lick in terms of tonality. Over the first two measures we hit on a C major sound before moving to Dm triad to end it.

Click here for Ex. 5

These concepts work really well with country and Americana music as well. Ex. 6 is a hip double-stop lick in C that perfectly outlines the “C” shape in the key of F and the “A” shape in the key of C.

Click here for Ex. 6

Finally, Ex. 7 is a more linear country-style lick in the key of C. By now, you’ve played enough of the shapes to get a handle on visualizing the neck. Can you guess which shapes this lick uses?

Click here for Ex. 7

Spoiler: It uses the “C” and “A” shapes.

If this approach seems too simple to use in the “real world,” take a look at the work of master guitarist and songwriter Mark Knopfler. Here’s some early footage of Mr. Knopfler playing “Sultans of Swing.”

If you look at the fills he plays between the vocals, you’ll notice that he sticks almost entirely to melodies built around major and minor triads. See if you can recognize some of the ideas and shapes, using what we covered earlier as a guide. If you have particularly sharp ears, you might also notice that he only occasionally strays from the original recording, and largely plays the fills the same way he laid them down on the original track.

One of the mixed blessings of writing a hit song is that its appeal tends not to fade with age. In other words, if you are lucky enough to have one, you’re going to have to play it more than just a few times. This could become wearing if you don’t develop the ability to improvise.

In this second version of “Sultans,” filmed nearly four decades later than the previous one, you might notice the fills happen in the same parts of the song, but Knopfler’s note choices are quite different. This means he’s generating new material on the flywithout changing the concept behind the material itself. He is improvising beautifully, and has been for decades now, using largely a combination of triadic ideas and the pentatonic scale.

If triads are good enough for Knopfler, they are certainly good enough for the rest of us! We’re a couple of steps away from being able to use this concept properly, because we need to see these triads in the context of a chord progression. If you are an advancing player, it’s a good idea to start working these ideas through the harmonized major scale as soon as you can. Allow your ear to guide you, and your new knowledge to support your growing ear.