Being asked by Premier Guitar to write an article about lesser-known vintage spring reverbs was like a chocoholic being asked if he’d like to become head taster for Willy Wonka. As the founder of Soundgas Limited, my self-proclaimed remit over many years has been to seek out and explore vintage and unusual recording gear, with a particular emphasis on effects—especially electromechanical echoes and reverbs. Based in Derbyshire, U.K., Soundgas supplies a unique range of classic, esoteric, and exotic music-making equipment to a stellar international client list. As soon as the remit for the article was confirmed, I set about sourcing as many vintage spring reverbs as I could find in the limited time available.

If, like me, you grew up in the pre-digital age listening to music radio, you’ve heard countless examples of classic spring reverbs in action. From subtle sweetening ambience to canyon-esque magnificence and surf-drenched tsunamis, popular music is awash with the sound of the spring reverb.

I was a music-hungry teenager when I first became aware of the spring reverb as a distinct entity. The mid-to-late-’70s U.K. music scene was enriched by the coming together of punks and dreads, united by common bonds of alienation and exclusion. The Clash were my introduction to reggae legends Junior Murvin (Police & Thieves) and Willie Williams (Armagideon Time). We became aware of Lee “Scratch” Perry and King Tubby, and marveled at the exotic and otherworldly sounds of Jamaican sound-system culture. This was to have a profound and lasting influence on my future life: Without dub music there would be no Soundgas. The wild, rolling repeats of endless tape echoes, deep organic phasing of guitars, hi-hats, and organs, and of course the thunderous crash of abused spring reverbs—sounds that, to this day, are manna to me.

Prepare to Reverberate

Ever since the introduction of outboard spring reverbs, classic models that are commonplace in the U.S. have been about as common as hens’ teeth in the U.K. Even with the advantages of the internet, these are difficult to acquire for comparison’s sake without exorbitant cost. The most glaring omission you’ll find here is the original, tube-driven Fender Reverb—although plenty has been written about this fantastic unit elsewhere. We did have the British answer to the Fender in hand, in the shape of a rare, nicely restored 1963 Vox Echo Reverberation Unit. In total, I directly compared over 25 vintage spring reverbs and half-a-dozen modern pedal options.

Before we dive into the springs, I have to confess that I cannot fairly describe myself as a guitarist. I enjoy making noises with guitars and effects, and have had a lifelong passion for all things guitar related, but it’s unlikely I’ll be interviewed in these hallowed pages about the secrets of my technique and tone. Sound is my thing: The studio and its myriad sonic playthings are my instruments, and spring reverbs are a particular passion—the weirder and less known, the better. For the purposes of comparison, I used a loop pedal with guitar parts played by a member of the Soundgas team, Joel Kidulis, to ensure there was no deviation in playing.

Along the way, there were a few surprises, with some units completely confounding my expectations. Perhaps unsurprisingly, some springs we rate highly for studio and mix use fared less well with guitar, having not been designed for that type of input. Others have very short springs and are more suited to vocals. Some that we prize for their unique character sounded noisy and uninspiring with guitar. As a result, I edited my original selection down to the highlights. I’ve given some background on particular units and brief notes on performance, but please check out the sound examples for the real lowdown.

Background Noise

While this article is not intended to be a definitive guide to all things spring, some background history and technical detail is necessary to understand the nature of the various units on test.

The first spring reverbs were large, oil-filled devices developed by Bell Labs to simulate the delays caused by long-distance telephone cables. In 1939, Laurens Hammond employed this new technology to add church-like ambience to his organs. Over the years, Hammond engineers improved and refined the company’s spring reverbs, reducing them in size and weight, until in 1959 the Hammond (later Accutronics) Type 4 was born. Featuring two long springs inside a 16" metal case, the Type 4 soon became the industry standard. Hammond licensed the design to other manufacturers, including Leo Fender, who used it in his 6G15 Fender Reverb in 1961. In 1963, the Fender Vibroverb became the first guitar amp to feature onboard spring reverb.

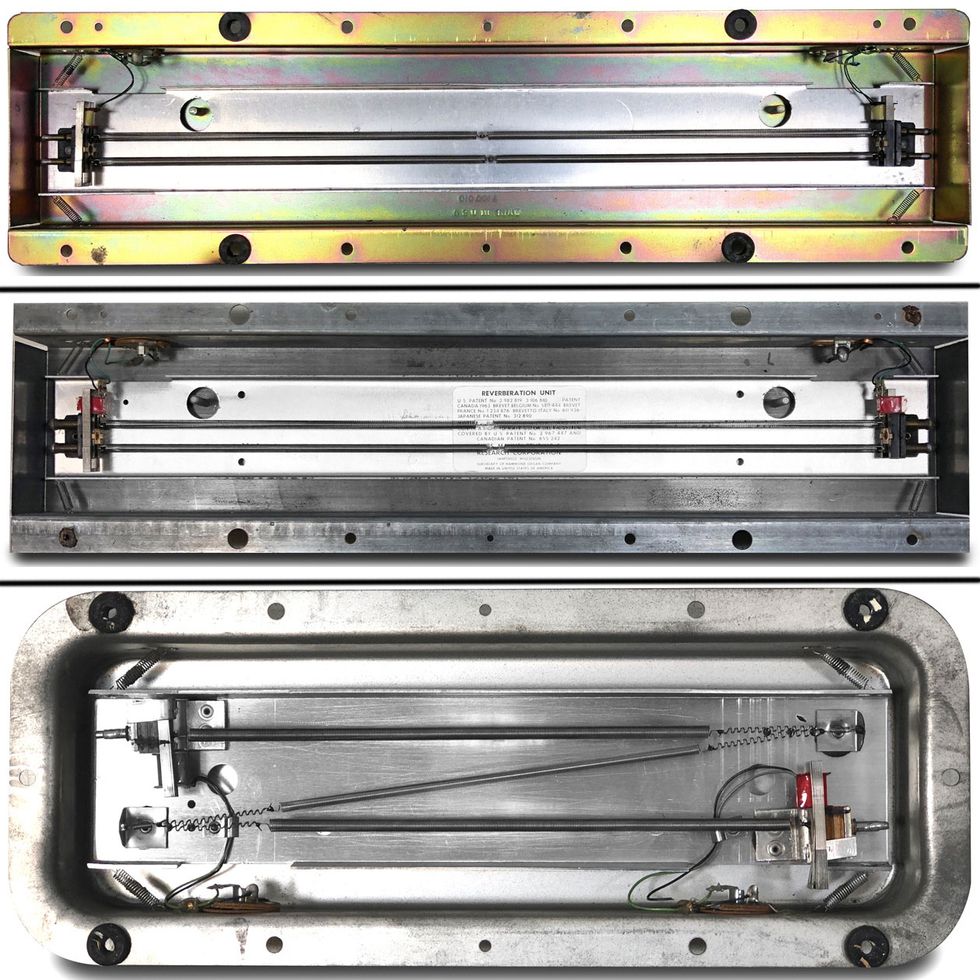

Evolution of the spring tank: The original Hammond Type 4 tank (top) has a brass-like hue on the underside of its welded chassis, while sister company Gibbs’ version (middle) is almost identical save for the sharp corners, and the competing O.C. Electronics Folded Line Reverberation Tank (bottom) (with its famous “Manufactured by beautiful girls” label, inset) houses its innards in a tray made from a single piece of bent metal.

Initially, Type 4 tanks were produced in-house at Hammond, with production moving in 1964 to Gibbs Manufacturing, a Hammond-owned facility in Janesville, Wisconsin. In 1971, it moved to another Hammond company, Accutronics, in Geneva, Illinois. One of Accutronics’ biggest competitors—formed by ex-Gibbs employees—was O.C. Electronics, whose Folded Line Reverberation Tank was used in Roland's Space Echo series and bore the legend: “Manufactured by beautiful girls in Milton, Wis. under controlled atmosphere conditions.”

Spring reverbs can be divided essentially into two camps: those that passively mix the spring output with the dry signal, and those that use a make-up amp or buffer circuit to add gain to the signal. The two biggest factors in the sound quality of a spring reverb are type and design of the drive circuit and the tank. Most units feature two or three springs. Two sound more fluttery and “vintage,” while three tend toward a richer, smoother, fuller sound with more low end.

Listening to the clips, you’ll find that some of these units are capable of creating way more than ambience. Whether driven by germanium transistors, 4558 op amps, or discrete preamps, vintage spring ’verbs tend to have a wealth of tonal colors lurking beneath their surfaces. Pushed hard, many can get properly nasty. And sure, they’re not exactly pedalboard friendly, but the tones from their drive circuits can rival some of the most coveted vintage overdrive and fuzz pedals.

Listen to most of the reverb units in a direct comparison.

Meet the Lords … and Gollums

1963 Vox Echo Reverberation Unit

Made in the U.K. by Jennings Musical Instruments, Tom Jennings’ answer to Leo Fender’s Reverb uses an EZ80 rectifier valve, as well as two 12AX7s and one 12AU7. It has two input channels to Fender’s one. These early units are very uncommon. Later in 1963, following an endorsement deal with the Shadows singer, they became known as the Vox Reverb Unit (Cliff Richard Model).

The Vox’s unusual design incorporates two sets of springs and four delicate ACOS crystal phono cartridges instead of the Hammond tank’s pickups and transducers. According to Vox designer Dick Denney, this was to circumvent the Hammond patent and avoid having to pay license fees. As you increase the level of the spring, the overall output level drops, so careful balancing of amp and effect can be required to achieve the desired sound. The crystal pickups in these units do not withstand the passage of time and this particular unit has had modern replacement phono cartridges installed to keep it as authentic as possible, though I personally feel it would probably sound much better with a Hammond tank! It’s a subtle yet warm and sweet effect that suits guitar well but is less likely to appeal to those seeking a wetter surf-type sound.

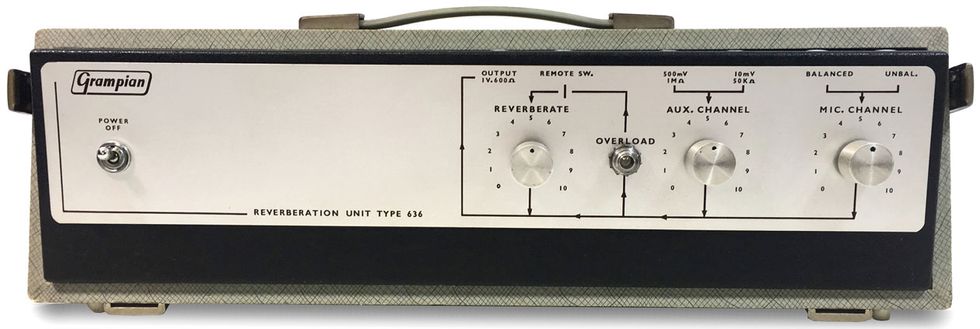

Grampian Reverberation Unit Type 636

I could write a whole article about this unremarkable-looking, gray Vynide-covered box from the U.K. It’s a true wolf in sheep’s clothing that links the Who’s windmilling guitar genius, Pete Townshend, with the godfather of dub and remixing, Lee “Scratch” Perry. Townshend discovered that plugging a guitar into the Grampian’s mic input—whose germanium circuit is very close to an early Fuzz Face—delivers a rich, distorted fuzz effect, which is why he employed one in the studio and onstage for many years. Meanwhile, Perry installed one in his Black Ark studio. In fact, Grampian reverbs graced many recording studios in the ’50s and ’60s.

Type 636s do not accept quarter-inch jacks, and instead use BBC/GPO type-b quarter-inch sockets. The mic input has balanced and unbalanced options, and there are two auxiliary channel inputs. The 10 mV, 50k ohm input is great for guitar—and also for maximum distortion levels. The second input is 500 mV and 1M ohm, and its output is rated at 1V 600 ohms. Controls include an on/off toggle, reverberate (reverb level) knob, and input gain controls for the mic and aux channels, which link to the overload-lamp circuit. The lamp is an integral part of the driver circuit: If it’s not working or of the wrong value, performance can be adversely affected.

The 636 is capable of smooth, rich reverb with low noise. However, given the age of the original germanium transistors, many unrestored examples are now quite unstable and noisy. We have a couple in the studio—one with the original Gibbs tank, and one with a replacement Accutronics tank—and we use them extensively for coloration. Both are featured in our sound samples for comparison. Initially, I expected these units to be some of the noisier reverbs in the test, but they performed better than most. A well-restored Grampian is a great contender if you want a high-quality studio or guitar spring. But it’s when you overdrive them that the real magic happens: The degrees of luscious filth on offer are widespread, controllable, and utterly sensational.

It’s hardly surprising that, as awareness has grown, 636s have become very sought after, with prices now well into four figures—even for units that need servicing. However, because they look so humdrum, they’re still sometimes thrown away as garbage. (The last one we got was saved at the last minute!) We’ve seen a fair few come and go at Soundgas and have successfully restored many. We’ve also seen a good number butchered by those attempting repair without fully understanding the circuit. Many were powered by a large, lantern-style 9V battery that can leak acid over time. I’ve seen 636s with the tank and much of the metal chassis completely eaten away. In addition, sustained high input levels can burn out the all-important pilot lamp bulb. Be very cautious if you’re considering purchasing one that hasn’t been refurbished, as few are likely to function as they should.

As mentioned previously, both my Grampians were in action for the shootout, but one developed a fault with the Gibbs tank. Our tech, “Doctor” Huw Williams, fitted it with an Accutronics tank to keep it in the game. The one still outfitted with a Gibbs tank is battle scarred, a little cranky, and somewhat noisier (all Grampians have a degree of hiss—the price you pay for that germanium magic), but it sounds more to my taste than the Accutronics-fitted one. But then, I like dark, warm, and mellow. The revived unit still has that fabulous break-up, but the Accutronics tank sounds brighter, much louder, and more reverberant—which gives me a compelling reason to keep both!

Soundgas is currently working on a new version of the 636. If we can get the sound right, we plan to build a few to order—although the scarcity of good new-old-stock (NOS) components means it’ll likely be a very limited run.

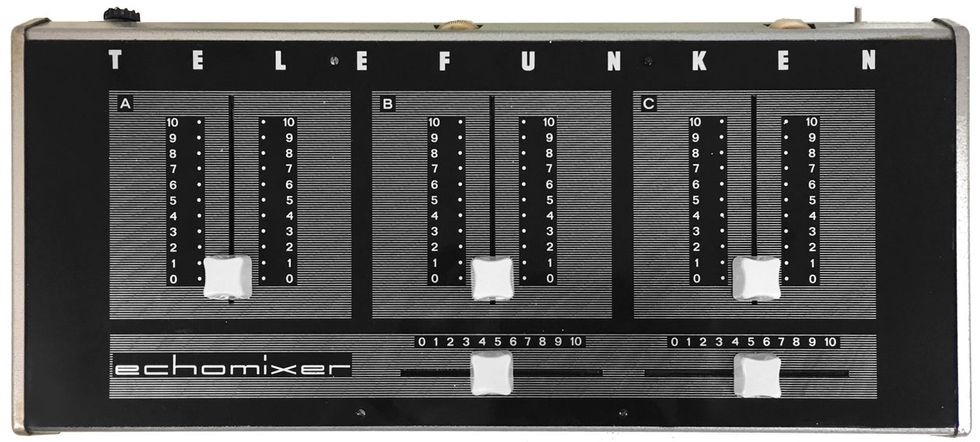

Telefunken Echomixer

The German-made Echomixer has been something of a secret studio weapon for some time. It features a simple, germanium-transistor drive circuit feeding a Gibbs tank and no recovery amp. Operating as a 3-channel mono mixer, the Echomixer is very suited to use with guitar whether you’re playing live, recording, or mixing. Given the vagaries of germanium-transistor aging, you’ll often find subtle—or stark—differences between the three channels, expanding what was an already-pleasing sonic palette. Channel A has no reverb, but channels B and C have low- and high-sensitivity inputs. Cream-colored wheels control input gain, allowing you to dial in overdrive, while the horizontal sliders below each channel mix in the reverb effect.

As with the Grampians, these units often require work to get up to spec—and also to interface with today’s users: The inputs are 5-pin DIN sockets rather than quarter-inch inputs. We modify them with a wet-only switch and quarter-inch input, and upgrade the trailing lead output jack to a more robust modern variety. The reverb sound is fuller and smoother than many of the other units on test here, and the added option of being able to dial in delicious warm germanium distortion makes this a firm favorite for guitar and mixdown use.

Roland RE-201 Space Echo

The Japanese-made Space Echo is included here as a benchmark due to its ubiquity. Most well-equipped studios have one in a corner somewhere, because even if the tape-echo section isn’t working well, the reverb is not to be ignored. We love RE-201s, and the spring tank is a big part of the appeal. The Space Echo’s discrete preamps can work very well with guitar and get wonderfully crunchy when pushed. Because they were made in four separate factories, RE-201s actually come in several circuit varieties, and they can have very different tonal characteristics. It’s always worth trying a 201 (or 301, 501, or 555) if you’re looking for another reverb flavor, as the Roland spring sound is very classy indeed.

Roland VX-55 Mixing Amplifier

I’m a big fan of the old Roland PA mixers from Japan. They have the same spring tank as the Space Echo range, but, unlike the discrete RE-201, their input amplifier uses a 4558 op-amp chip—which means you get the added bonus of gnarly distortion when you drive the inputs hard. (The 3-position switch by the input socket for each of the six channels yields instant access to a range of colorful options). Add to this the fact that each channel has a 2-band EQ and a switchable mono effect send/return (if you don’t want to use the onboard spring effect), and you have a potent stage and studio tool. Simply use the line out to go into your amp, mixing desk, or recording interface. And with so many channels available, you can get creative with mixing your other gear or bandmates, or use it as a submixer for your pedals. In all, the VX-55—as well as the similarly equipped VX-60 and VX-120, and the later PA-80, PA-150, and PA-250 mixers, all of which feature the same spring tank—constitutes a great option that you may just pick up at a thrift store or garage sale for a song. And they work as neat little PA amps, as well.

Korg Stage Echo SE-300

Another Japanese wonder comes in the form of Korg’s Stage Echo. It’s not as common as the Rolands, but well-maintained examples tend to sound clearer and cleaner as delays. The spring tank offers a longer decay and sounds great with guitar, possibly because of a slight 3kHz peak.

Guyatone Flip FR 3000V

The Flip was a Johnny-come-lately, both to the market (relatively speaking) and to this shootout. (The one I ordered arrived the day after I submitted the original version of this article, though we managed to shoehorn it in.) Released in the late ’90s or early 2000s and now discontinued, this Japanese pretender to Fender’s crown is solidly built, features NOS tubes, and a long-spring Accutronics tank. Everything suggests a quality unit, and it’s most certainly versatile—with controls not just for input level, reverb volume, and master volume (which yields some saturated tones), but treble and bass controls, as well. The reverb character is quite bright, but it’s a competent performer and feels ready to handle gigging for the next decade. We’re going to try a few experiments with this one and see whether a different tank—perhaps a vintage one—and a few mods can make it a giant killer!

Roland RV-100

Also badged as the Boss RX-100, this visually unprepossessing little black plastic box was something of a revelation. It features two tanks with switchable reverb times in either parallel (shorter) or series (longer). I wasn’t expecting much, given the size of the unit, but it turned out to be a competent performer, delivering a smooth, pleasing reverb that belied its diminutive stature.

Pioneer SR-101, SR-202, and SR-202W

Made in Japan for the U.S. market, these units were sold in the ’60s and ’70s to add extra “life” and atmosphere to domestic hi-fi systems. With their RCA inputs and outputs, the SRs were designed to accept home-stereo component-level signals, but that hasn’t stopped them from seeing other action. They’ve become popular with some mix engineers for the very short, dark, and fluttery echo from their small spring tanks. Superstar mix engineer Tom Elmhirst (David Bowie, the Kills, the Black Keys) used these to great effect in his mixes for Amy Winehouse and Mark Ronson. Unfortunately that magic doesn’t translate to the guitar realm. They fared very poorly with electric guitar—lots of noise and a poor reverb sound. We also have a similar Sansui RV-500 unit, but at the time of the test it was humming loudly and required further attention.

Fostex Reverb Unit Model 3180

One of a range of units made to complement Fostex’s reel-to-reel recorders, these 2-channel, twin-tank units from the ’70s are wired in series for stereo operation. I expected the 3180 to be unremarkable for guitar, like the Pioneer units, but was surprised to find the sound pleasingly smooth, with a low noise floor. The quarter-inch jacks make this an easy option for a different sound, and if you’re lucky you may well find a bargain in a thrift store or yard sale.

Hawk HR-101 and HR-202

These budget Japanese units were made for the domestic market—hi-fi, home recording, or, most likely, karaoke—and use a bucket-brigade-device (BBD) chip to make up for the poor quality of the spring tanks, adding a little pre-delay to separate the trashy wet signal from the input to give the impression of better-quality reverb. As a guitar reverb, they’re not great (the output is from RCA sockets) and the sound is trashy and fluttery. But their op-amp driver circuit makes them great distortion boxes for studio use with louder source material.

Shin-ei ER-23 Echo Reverb Master

This pedal-like unit from the famous Japanese maker of fuzz boxes (including the Univox Super Fuzz and Shaftesbury Duo Fuzz) doesn’t appear to have made it outside the domestic market, which is a shame. Not only is this mains-powered unit a delight to behold (I know of two versions: silver with orange accents, like the one here, and white with red accents.), but it actually works pretty well. Don’t be fooled by the footswitch, though—that’s the power button. The diminutive size means you’re never going to get a big, lush reverb out of it, but it does a great impression of a cheap reverb amp, and the mic input can drive you into hairy, lo-fi distortion.

Bandive Great British Spring

This infamous British unit features a pair of Accutronics tanks housed in a length of grey or black plastic drainpipe. Available in mono-unbalanced or dual-channel balanced configurations, the Great British Spring is a capable, smooth-sounding unit for use with a mixing desk, and can sound lovely added to guitars at the mix stage. But, as its dual-XLR ins and outs make it difficult to use directly with guitar, we left it out of the final audio comparison.

Bandive Accessit Stereo Spring Reverb

With a design similar to its Great British Spring sibling, the Accessit has two pairs of op amps in the drive/recovery circuit, and can overdrive pleasingly when driven hard. It also has a passive, single-band swept EQ knob, which is nice and flexible for tone shaping.

Fisher Dynamic Space Expander

This U.S.-built, tube-equipped reverb features the sort of Gibbs tank originally used in Hammond organs and sought-after by dub aficionados due to its association with King Tubby. This was another of the units that didn’t fare well with guitar. We’re looking into whether it might be possible to modify it to perform better with guitar, but in standard form it proved extremely noisy.

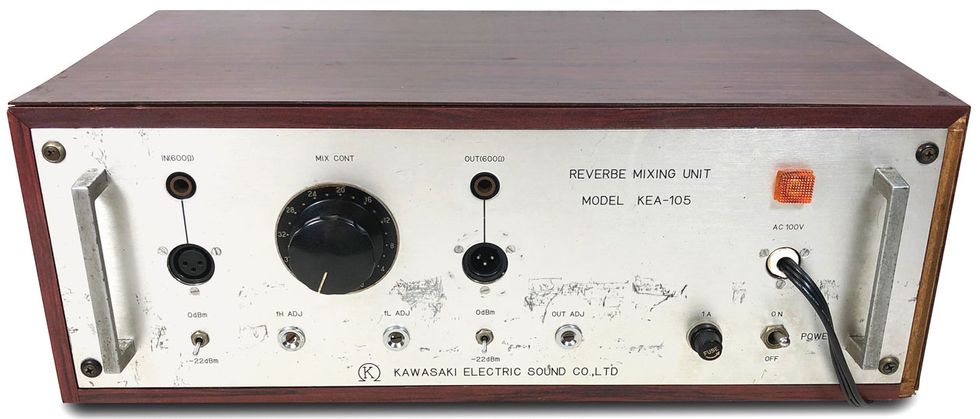

Kawasaki Reverbe Mixing Unit KEA-105

Possibly a one-off custom build for the Japanese broadcast market, this no-expense-spared unit features three two-spring tanks with springs made of different materials, and a middle tank that’s wired out of phase. Further, it has input and output transformers, as well as transformers on the driver and make-up amp. It weighs a ton, but sounds so nice that it’s permanently installed in the Soundgas Studio. I’ve never seen another like it.

Simms-Watts Mixer Unit Hammond Reverb

This rather uncommon British unit (which has an enticing EMI logo on the rear) boasts four input channels and a Hammond tank (possibly from an L-100). I’ve had mine for many years and haven’t seen another until somewhat recently. Very little is known about Simms-Watts other than it was one of a plethora of U.K. amp builders who disappeared after a few years in the ’70s. I kept this one, as I found it vastly superior to similar Laney and Carlsbro units I’d had. The sound is full, rich, and reasonably smooth—which I suspect is mostly a testament to the quality of the tank. Mine may be ready for a little TLC, as it didn’t sound as good in the shootout as I remembered.

Klark Teknik DN-50

This twin-tank unit from Britain was probably designed for front-of-house use and features two channels, each with dual-band EQ. Most of the units designed for studio use have not fared so well with a guitar plugged in direct, but this was an exception. Plug into the quarter-inch jack under the rear panel’s balanced XLRs, and it yields a smooth, full sound with impressively flexible tone-shaping abilities.

AKG BX-5

Although best known for its microphones, German outfit AKG also made a range of superb spring reverbs, of which this is the baby. The top-of-the-line models, the BX-20 and BX-25, are large, heavy, extremely complex and delicate units with a smooth response unlike any spring reverb I’ve heard. But while the BX-5 is a competent recording and mixing tool, it didn’t fare well as a direct guitar effect.

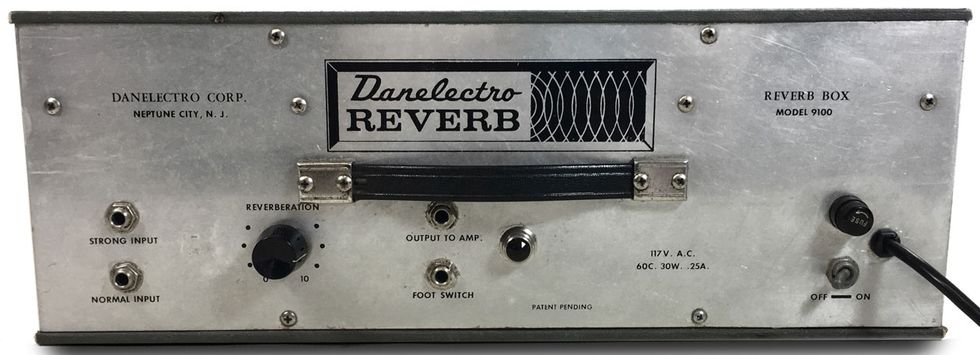

Danelectro 9100

Sadly, this shiny box is no longer with us, so we weren’t able to share audio files for comparison, but this product of Neptune, New Jersey, was quite something. It served up classic tube reverb with a long decay. Once heard, it’s never forgotten. Definitely one to check out, although it’s easier to find in the States than here in Europe.

Final Thoughts

I had a real gas comparing these units. I knew I’d love the Grampian and the Telefunken, but I was bowled over by how good the Rolands and Korg sounded as guitar reverbs. We at Soundgas are also no strangers to abusing and overloading mic inputs to turn things really filthy—it’s in our DNA—so I was very taken with how well many of these reverbs performed as overdrive or fuzz units, as well. I’ve learned to never dismiss a reverb simply because it wasn’t designed for guitar—I’ll try everything at least once. The worst that can happen is you might not like the sound. But if fortune smiles, you might just discover a whole new ocean of sun-drenched delights.

Here are all the audio clips for most of the reverb units so you can compare them in real time.