There is a restless energy and enthusiasm in the way J.R. Bohannon speaks. Whether discussing his practice routine, his favorite musicians, or his ambitious musical plans, he’s passionate and effusive. His is an indefatigable spirit. “If this wasn’t the only thing in the world that eased my mind and let me live a normal existence … if I could do anything else, I probably would. But I can’t! This is the one thing that gets me up in the morning, and it’s the one thing I look forward to, going to bed at night.”

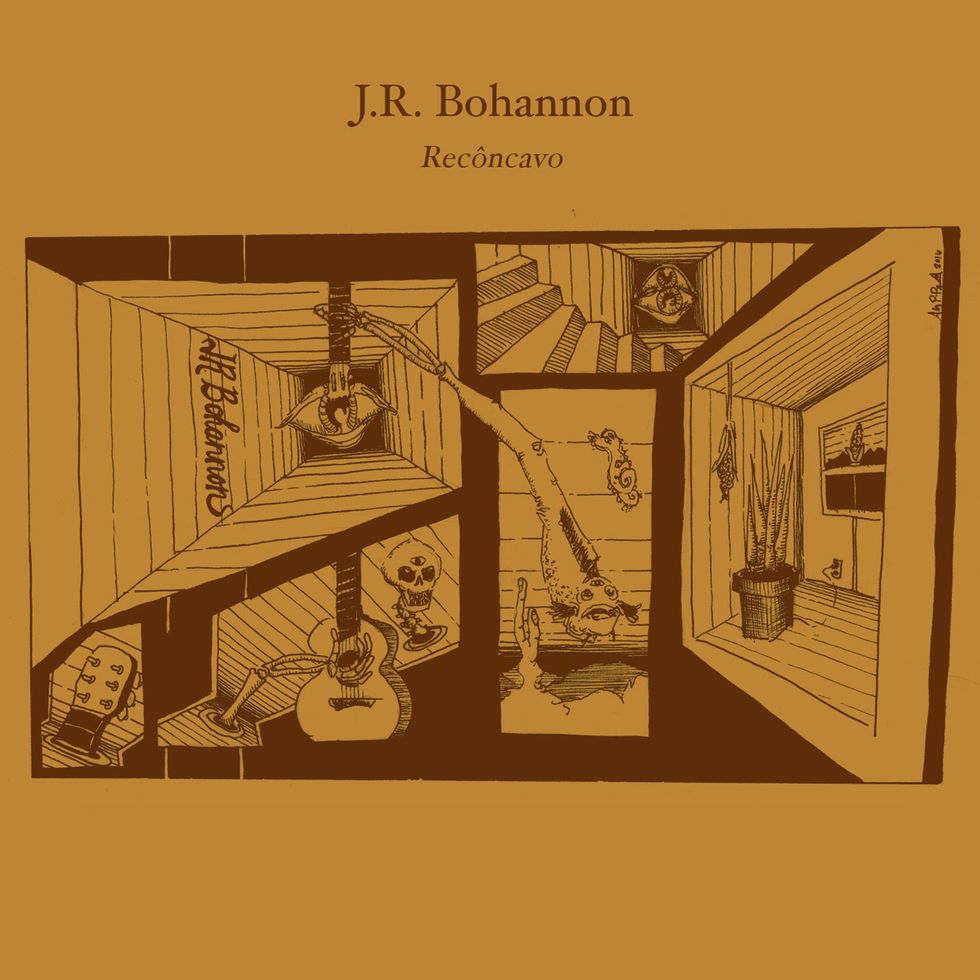

While discussing his latest EP, Recôncavo, it’s clear Bohannon is already excited to talk about his next album, Dusk, which is due out sometime this fall. His reason is quite understandable: Though recently re-released (more on this in a minute), Recôncavo was actually recorded a couple of years ago. But we were able to convince him the five-song EP is worth some attention before moving forward, because—in addition to being a record that brings a new angle to the solo acoustic tradition—it’s also a crucial part of Bohannon’s story.

The 31-year-old guitarist left the South for New York in 2009 with his eye on the city’s experimental music scene. He dove in head first, leading the ambient psychedelic solo project Ancient Ocean and jamming in ad hoc improv bands around the city. Once he’d been there a while, he discovered he was ready to rekindle his relationship with the music of his home. “Growing up in Louisville, being around Southern music traditions—country, bluegrass, Appalachian music, things like that—those were things that I heard but didn’t necessarily connect to at that time. I couldn’t stand country music back then because it’s everywhere, it’s shoved down your throat. [But when] I moved to New York, I started rediscovering that music in my own way. And then it gained a new meaning. Now, it’s my favorite music in the world.”

A couple years back, Bohannon decided it was time to get back to basics with a new project that used his own name. He began with a solo acoustic record, taking his time collecting the material for Recôncavo, recording and re-recording songs in various settings until he was ready to self-release the EP on Bandcamp and a small run of cassette tapes in March 2017. The result was a focused exploration of Bohannon’s wide range of deeply investigated personal influences, from the classical guitar music he studied as a teen to the Brazilian music he immersed himself in during college—and, of course, his newfound enthusiasm for country and experimental music. In April of this year, Recôncavo caught the attention of British label Phantom Limb, which was so enthusiastic about the recording that it offered to bring wider attention to it via re-release.

We recently chatted with Bohannon about the creative process behind both the EP and his upcoming full-length, and got more of his intriguing backstory.

You first started playing guitar by taking classical lessons when you lived in Louisville, right?

Yeah, I took mostly classical guitar lessons through my teens. I wasn’t really into the idea of classical guitar music, but I liked the techniques. At the time I was listening to a lot of Elliott Smith and Leo Kottke, so I loved the fingerpicking sound but I didn’t necessarily want to play classical music. In Kentucky, you either have to do that or take bluegrass lessons, and I didn’t want to do that either. It was kind of a combination of lessons and self-teaching as well. It was still a pretty early time as far as the internet and tablature goes—you still had to listen to stuff and figure it out for yourself. There was no YouTube, basically, so it was a little more of a challenge. I didn’t start taking it super seriously until I got into college. I grew up in the suburbs and my parents had different expectations than me becoming a musician, so that kind of weighed on me until my mid 20s—that pressure to have some kind of “normal” career. But time goes on and you realize there’s no such thing as a normal career. You just have to go full speed or don’t do it at all, in my opinion.

What sounds were you chasing that led you to move to New York?

Experimental music, free jazz, spastic balls-to-the-wall psychedelic music … the weirdest shit I could find. My favorite band at the time was Acid Mothers Temple, and I was listening to lots of Albert Ayler and Sonny Sharrock, so I wanted to move to New York and be around that. It’s funny because, living in the South—or anywhere where the pace of life is slower—I think it’s easier to digest experimental music, especially recorded, because life is not as chaotic. In New York, life is so chaotic, the last thing I want to do is hear some spastic free-jazz record. I still love that stuff, but I don’t have the space of mind for it on record as I did when I was 21. Now, when I’m home I want to listen to George Jones and ambient records. I don’t want it to take up too much space.

TIDBIT: This free-ranging album assays Bohannon’s treasure trove of influences, focusing primarily on the classical guitar he studied in his teens and the Brazilian music he devoured in college.

Listening to Recôncavo and Dusk, one hears references to American primitive guitar playing—you mentioned Leo Kottke—but also things like Brazilian music. How did that develop?

When I was in late high school, a friend gave me the [1968] self-titled Caetano Veloso record, and I fell in love with it—and with everything about Brazilian music—and got very obsessed. I studied abroad there and spent some time traveling around. I love not only the tropicália stuff, but I love the traditional música popular brasileira—MPB is what they call it. It’s the popular music of Brazil. A lot of those guys had a lot to do with the influence of timing and rhythm in my playing. If there’s one thing that gave to me as a guitar player, it’s that I don’t feel inclined to stay in one tempo or play to a click. I like to just go to my inner rhythm. When I play, I’m shifting in my seat because I’m kind of mustering up all these things in a way that I’m free flowing, rhythmically. I’ve listened to so much Brazilian music and spent so much time with it that a lot of the rhythms have become ingrained in what I do.

Both recordings sound aesthetically focused but use elements of the different styles you mentioned. Each track sounds like it’s thoroughly exploring a concept.

A few years ago, I said I’m going to really make a go at this, at playing guitar, and one thing that was really important to me was to not rush it. I recorded those songs [on Recôncavo] two or three times, and this next record probably three times all the way through, and just scrapped it. I just like to let songs grow over time. You know the way some people like to write and record, and then it’ll grow on the road? I like to do the opposite: I like to record something in its fully realized form, and I want it to be not only technically sound, but it needs the room to breathe. That’s something I strive for—to just let melodies breathe and play slow. I think you hear a lot of someone’s playing in the subtle nuances.

Were all the tracks on Recôncavo recorded in different places? Apparently “Under the Friar’s Ledge” was recorded in a hotel room….

Everything was recorded in different places. I pretty much travel with a mobile rig, just so I can get down ideas. Two tracks were recorded at home, one was recorded at a friend’s house, one was in a hotel room, and the fifth one … I don’t know where it was recorded.

What do you use to record?

I have a Tascam 388 [1/4" reel-to-reel 8-track], and I have some gear at home. I do a lot of recording myself, and everything I’ve done I’ve mixed myself. I’ve never given a record of my own to somebody else to mix. I feel like the way I sculpt things, sound-wise, comes through the way I mix. Maybe not as much on the EP, but on the next record there are a lot of layers. I’ve been making ambient records that are intricately layered for the last decade. I’ll have 50 tracks, and the way I put them together on my own is just as much of a creative process as playing the instrument.

A Fender Deluxe Nashville Telecaster is Bohannon’s go-to electric—perfect for both his country side, and an excellent workhorse for wilder 6-string inventions. Photo by Alex Phillipe Cohen

Near the end of Recôncavo’s “Fluctuation Pt. 1” there are some cool percussive, chime-y sounds. What’s going on there?

When I was recording I had my earbuds in, but I’d taken one of the earbuds out and it was dangling against the strings. I was like, “What is that sound?” It was really, really quiet and faint. So then I just boosted it really loud, took a bunch of the noise out, and literally scraped earbuds against the strings and bounced them against my 12-string. It just created this weird little percussive sound that’s really dense and textural.

It sounds very intentional.

The way I did it on the recording was, but the way I came to it was not. It just fell in there in its own natural way.

How do you feel like you’ve changed between the recording of Recôncavo and the recording of Dusk?

I think I’ve become a better player and a more patient player. The main thing is that I stopped feeling like I had to make an all-acoustic record. I felt that pretty strongly—that I wanted my first full-length to be 100 percent acoustic—but then I was like, “Whatever. That’s not what I am—I do a lot of different things.” I decided to make it the focus, but it doesn’t have to be everything. I let myself expand a little bit. That’s when I decided to take [Dusk] to a studio, to let it breathe a little bit and do overdubs. That also forced me to just do it rather than just sitting there and recording tracks in my room.

How do you approach the writing process?

When I sit down to write something, I do sit down intentionally to write something. I think the whole mindset of writing “when it comes to you” is bullshit. You’ve just gotta play and play and play. I’ve spent four hours playing and getting nowhere, and then in the fifth hour, there it is. Sometimes you really need to dig in there.

There’s still so much that can be done with songwriting. Song form can be whatever you want it to be. I’m interested in taking things that I love, especially simplistic things, and recontextualizing them. Like, on the next record that’s coming out, I do a pedal-steel version of a Ryuichi Sakamoto tune. And I’m going to do a Donald Byrd cover and recontextualize that in different ways. That’s what I’m interested in. That and the sheer joy of playing.

I get the impression you’re a big practicer. What are you working on at the moment?

These days, I’m playing pedal steel and guitar. I’m really trying to get to a point where I can do the lead country thing and the lead pedal-steel thing and do proper chicken-pickin’. Stuff like that. So I’m still practicing two or three hours a day, at least, because that stuff is labor intensive. You’ve got to put the hours in, because it shows. I’m really enjoying that at this phase of my life, because it’s almost meditative.

Guitars

1970s Guild F212

1970s Guild D55

Fender Deluxe Nashville Telecaster

Superior Weissenborn

Gretsch squareneck resonator

Carpsteel Rains pedal steel

Amps

1976 Fender Twin Reverb

1960s Ampeg Reverberocket

Kalamazoo Reverb 12

Effects

None

Strings and Picks

Various La Bella sets

Dunlop medium thumbpicks

Dunlop .013 mm and .018 mm brass fingerpicks

Have you learned any lessons from playing pedal steel?

Playing pedal steel opens my eyes hugely to how I play 6-string. To play pedal steel, you have to have knowledge of theory, and you’re always looking for how to get from point A to point B and visualizing it before. So I’ve taken that to my guitar playing, and it really helps me.

What’s your practice routine like?

I have terrible ADD, but I make it work for me: I always have my pedal steel set up, I have a synth set up, and I’ll have a book next to me. If I’m losing thought on one thing, I’ll quickly switch to something else instead of meandering too long. Instead of sitting down and doing one thing, I’ll sit down and do three or four things and, over the course of the day, I’ll have made progress on all of them. When people talk about rigorous practice regimens, it’s like 20 minutes on, 15 minutes off. You can kind of cheat that by moving on to something else and coming back.

Something that’s helped me a lot is that I don’t make to-do lists the night before anymore. I always do it day of, so when I come up with what I’m going to do, that’s what I’m inspired by that day. I used to let myself down a lot, because I’d make this list for the next day and then I’d be like, “I don’t want to do any of this.” So I stopped doing that completely, and it changed everything for me. Now I say, “These are the three things I want to focus on today, and here are three things I kind of want to focus on.” Those main three things I’ll make myself come back to, and those other things I’ll just float in and out of. At the end of the day, I’ve usually gotten those things done, or at least made progress.

How do you approach alternate tunings?

I find myself in traps of doing the same thing over and over, so I’m constantly looking for new tunings. Obviously, there’s a reference point—open G and open C, or whatever—but I’m always just fidgeting with whatever I can find. It doesn’t really matter to me if it makes sense or not. If I can find a chord voicing that’s cool in a weird tuning, that’s great. On my 12-string, for example, on the 5th and 6th [pairs of] strings I only have one string, and on the 1st through 4th [pairs] I have two strings. So on the bottom I can play melodies that are more distinct and do rhythm things that are more chime-y. The cool part about 12-string is, if you tune each of the two strings to different things, it’s a completely unique thing. There’s more room for exploration. Both records are kind of indebted to this exploration.

Doing side work now, I have to play in standard tuning, but up until a couple years ago I hadn’t played in standard for about a decade. I’ve been enjoying playing in standard everyday, and it’s brand new to me because I never understood it. Standard tuning on a guitar is the weirdest thing on the planet to me.

Arpeggios abound in J.R. Bohannon’s lush improvisation with fellow acoustic 12-stringer Alexander Turnquist. This minimalist-inspired piece is a great introduction to Bohannon’s playing and aesthetic.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Shop Scott's Rig

Shop Scott's Rig

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)