Jersey Girl Homemade Guitars is like something out of a Haruki Murakami novel—minus the supernatural freakiness and high odds someone will end up trapped in, dead in, or wandering to a new dimension through a deep, mysterious well that nobody seems to know about.

Allusions to classic American rock ’n’ roll? Check. Luthier Kaz Goto’s love of the classic Tom Waits tune inspired the name of this Hokkaido, Japan, outfit, while his affinity for Tom Petty inspired his first two guitar purchases as a kid—both Fender Telecasters.

As for Murakami’s idyllic communal settings where passionate, meticulous craftspeople dedicate untold hours to esoteric pursuits that astound everyday folks, check on that, too. In 2012, Kaz and his two JGHG partners, wife Eiko Goto and fellow luthier Akiko Oda, fled the hustle and bustle of their shop in Tokyo for a spacious countryside workspace that they’d spent a decade planning and prepping for. There, the trio spends its time alternating between raising vegetables and bringing to life some of the most visually arresting guitars you’ll ever lay eyes on—oh, and each one is paired with a matching custom stompbox and guitar strap.

For the 1Q84 fans out there, there are even Murakami-esque Little People. Or rather, one little “person”—only HAL, Jersey Girl’s mascot and all-around helper, is named after a character from a more iconic novel (more on that later).

PG first met Kaz at the 2018 Holy Grail Guitar Show in Berlin, Germany, and the museum-worthy pieces he played for us were some of the most alluring of the entire event. It was immediately clear there’s much more to the extraordinary effort and discipline that goes into making these instruments of precision and beauty than we could unpack in an 11-minute video, so we knew we’d eventually have to circle back and talk to Kaz to get more of the Jersey Girl story.

What made you decide to start building guitars, and when did you decide to do it as a career?

It was kind of an accident. I met Taku Sakashta when I was 19. [Editor’s note: The late Taku Sakashta was a Kobe, Japan, luthier who moved to California’s Bay Area in 1991 and made instruments for players such as Robben Ford and Tuck Andress.] He invited me to the guitar-making world and inspired me a lot. I ended up going to the Fernandes Guitar Engineer School in 1989 and was there for a year. For the last half of that, I was Taku’s apprentice. But then I left for a year to go work for the local jazz musicians' office, where I planned events and concerts, and helped musicians find gigs. At that time I was more interested in music than guitar making. After a year, Taku suggested I start making guitars with Akiko [Oda] as a partner luthier. She was at the same school for two years, and she was a student of mine for one of those. That was when I decided to start Jersey Girl Homemade Guitars, in 1991.

What are the most important things you learned from Taku?

I was so lucky to be close friends with Taku for a few years when we were both young. We’d stay up late in his little apartment in Tokyo almost every day, talking about music, guitars, and our dreams. He already had his own clear vision of how he wanted to be as a luthier. He taught me so much about guitar making, of course—but also about how to live life as an independent luthier. He said it’s important to keep your originality but not go too far away from what’s popular and accepted. It’s very hard to find the right point—I’ve been looking for that point with every guitar composition we’ve made all through the years. I really miss him.

Kaz installs the armrest on Seevie while HAL stands by with a hex wrench and a tuning fork at the ready.

Tell us about your background in music—what did you grow up listening to?

When I was 4 or 5 years old, in 1973 or ’74, I started playing music as a classical pianist. At that time I was very much inspired by Glenn Gould.

When did you start playing guitar?

When I was 13, after I started listening to rock ’n’ roll—especially Tom Waits and Tom Petty.

Who were some of your other favorite players back then?

Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, Lindsey Buckingham … classic-rock guitar heroes. Mark Knopfler is my favorite.

What about newer music?

I’m really into Chris Thile [of Nickel Creek and Punch Brothers]. I love his playing and his style on the mandolin. I’m always listening to newer bands and sounds on internet radio, too—but I’m not into just guitar music. I like Maggie Rogers, Aurora—a singer-songwriter from Norway—and Theresa Andersson, a singer-songwriter from Sweden who lives in New Orleans.

What was the first guitar you ever owned?

A Tokai [T-style] with two humbuckers. And then I got a Fender Telecaster with single-coils when I was 15 or 16. I played it through a blackface Fender Champ when I was in a covers band playing the Doobie Brothers, Grand Funk Railroad, stuff like that.

What were your own early guitar designs like?

I started JGHG to make original guitars. So we have been trying to make guitars unlike anything we have ever seen or heard. We learned a lot about what makes a good guitar by working in guitar repair. We were lucky to have a lot of vintage guitars to repair in Japan at that time—mostly Fender Stratocasters. Many of them had broken pickups, so I had to rewind them.

Aesthetically, your current designs are anything but traditional. Is the interior construction equally unconventional?

The solidbodies have a normal solidbody construction, but the hollowbodies usually have four or five different-sized chambers in them to yield unique tones. Our archtop guitars have a more challenging construction—we call it “dinosaur bracing,” because it looks like a brontosaurus. I notch out the bracing so it doesn’t dampen the top too much, so that it just controls the resonance.

Have you made any flattops?

Two or three, but just for myself. I’m planning to make some small-sized acoustics, like parlor-style, maybe later this year or next year.

A Crow on a Scarecrow, JGHG’s first archtop design, features a neck-block-mounted pickup and is paired with the company’s Middranger pedal—yet only half the instrument’s stunning elegance is visible to the casual observer. Inside it features the company’s equally remarkable “dinosaur” bracing.

JGHG’s Instagram says your guitars are built by four luthiers—yourself, Akiko, Eiko, and “a little luthier [named] HAL.” Tell us about that work dynamic.

From the very beginning, Akiko and I have worked together on all the guitars and effects. Basically, I draw the shape and come up with the overall design, and after that Akiko comes up with all the aesthetics—the inlays, the colors and finishes—while Eiko comes up with the strap designs. We work together throughout the whole project, but most of the looks of the guitars themselves are Akiko’s decision.

What’s HAL’s story?

He was born seven years ago. Akiko was very busy at work, so I made her a helper. We’d just started our Instagram account, and when she put his picture on there everybody started asking about him. So we made him our mascot. In Japanese, “hal” means “spring,” but his name was also inspired by 2001: A Space Odyssey—because HAL [HAL 9000, the sentient-computer antagonist from the 1968 novel and film] only has one eye.

Your HAL seems a lot friendlier than Kubrick’s.

[Laughs.] Yes.

Your Instagram also describes JGHG as “Composing guitars, [and] growing veggies.” Are the veggies part of the business—say, for making dyes?

They’re just for our table, but garden work helps us relax and enjoy each other’s company more. We had been living in Tokyo for a long time when we finally moved to our current location in Asahikawa, Hokkaido, seven years ago. There’s a big garden, so we started growing veggies and we found it very exciting to be doing that in this new location outside of the busy city. Our style of building has changed very much.

How so?

In the Tokyo days, my work was 70 percent repair work for professional players, so we didn’t have much time to make guitars. We wanted to stop doing repair work and only build our guitars. We actually decided to move to Asahikawa 10 years before we did so, because it was very hard to find a place here, and because we didn’t have very much money. In order to make the transition, we had to change our lifestyle and be more frugal, as well as stock up on materials.

Ten years—wow!

Not so much because it’s expensive or hard to find a place up here, but because I had a very specific vision for my workshop. It had to be the right place. I believe it’s very important to work in an environment that’s conducive to creativity. Creating guitars is very sensitive work, and it’s hard to do it right when you have a lot of people distracting you. Asahikawa is Akiko’s hometown, so I had visited here and liked it very much. It’s a beautiful countryside, and half of the year it’s covered in snow and is very quiet and calm. I felt like that calmness and solitude would help us focus. Plus, I could have more space to work out here. I don’t have a lot of equipment, but I wanted a high ceiling—not because I needed it for tall machinery or anything, but because most Japanese homes and buildings are small and compact, with lower ceilings. I wanted more space.

What background information should we know about the other members of your team?

Eiko is a singer-songwriter, and Akiko plays bass. The three of us play together pretty regularly. We used to play out once a month in Tokyo, but there aren’t so many places to play out here. We still record though.

Takutack is a side-less archtop whose soundboard is mounted internally, between the top and back. Its partner pedal is a preamp/mixer for the instrument’s neck-position magnetic pickup and internal contact pickups.

When did the ideas we see in your product line now first occur to you?

I’ve always tried to make our designs unique—but not too unique. It’s easy to find good-looking guitars but sometimes it’s hard to find really unique tones. I want to instill each guitar with a unique identity—not just in looks but in sound, too.

Among the many intriguing things on your instruments are your unusual pickup designs. How did you get into that?

I started making pickups in 1996, but it was difficult—it requires a very different type of knowledge than guitar making. But I wanted to use my own pickup designs in all our guitars. I started out making Stratocaster pickups, since that’s how I learned to make pickups—again, because of all the Strats I’d repaired over the years—and then I tried humbuckers. But I was also looking for “my” tone, so it evolved step by step. We think pickups are a very important part of guitar making, so we’re trying to find “our tone” in every instrument. Usually I wind two or three different sets of pickups for each guitar, and then select the one that complements the guitar the most. Sometimes they’re just different windings for different outputs, but sometimes I change the magnets and the heights. I’m always trying to find the right tone for that instrument.

How would you describe “your” tone?

I’m still looking for that! I want my guitars to inspire the player, and I want to hear new sounds from the musicians. The best I can say is that I’m trying to find inspiring tones.

When did you start doing your staggered-pickup designs?

I started thinking about the three-by-three design around 1998. I initially just wanted to reduce the noise from a single-coil, but I found that it was also a very unique tone—kind of in-between a single-coil and a humbucker. You can balance both the volume and the tone of the strings better. On Breath of Something Big, for example, all of the pole pieces are alnico 5 except the 2nd string, which is alnico 2—and that one pole piece is under the wood. I use alnico 4 magnets sometimes, too. All of those little nuances are there to help adjust the output balance. Sometimes—especially with an archtop or hollowbody guitar—there’s a big difference in loudness between plain strings and wound strings.

The pickups on Mayberlin are particularly intriguing—there appears to be 3/4 of a humbucker in the neck and bridge positions, plus half a single-coil built into the pickguard in the middle position.

It’s basically a three-single-coil guitar. The middle pickup can give it a more resonant or bright sound.

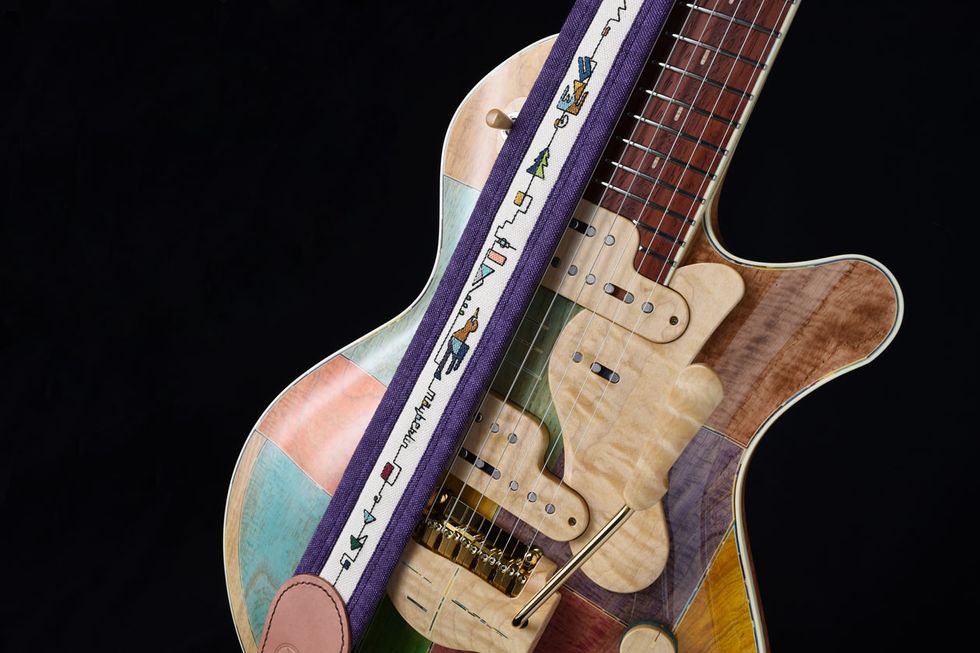

From its pastel palette to its perfectly nestled “three-by-three” pickups and the flowing lines of its pickguard and hardware accoutrements, Mayberlin and its neo-primitive-motif strap are a joy to behold.

What was it that first led you to build stompboxes?

Sometimes I would install a preamp in a guitar, and one time someone said they wanted me to put the preamp into a pedal. So I made it with the help of my friend Kenichi Shiho. That was our first pedal, the Middranger. That customer then showed it to Mr. Kishimoto at Ishibashi guitar-shop in Tokyo—one of the biggest guitar-store chains in Japan—and he was really interested and suggested I make it as a product. So we did. We released our best-selling overdrive, the Fulltender, in 1998. It has a unique preset tone selector that goes from “edge” to “bottom.”

When did you start building artistically themed sets—matching guitars, pedals, and straps?

We started making pedals in 1996, too, sometimes with wooden enclosures. Then, with some help from Heath [Berkowitz] from Boston Guitar, we were able to go to the 2004 Summer NAMM show—which was a big event for us. That was our first time going to NAMM. The next year, Heath helped us get a booth for Jersey Girl at Winter NAMM 2005. That was when we decided to make all our instruments with a matching strap and a matching pedal.

Does every JGHG guitar have a matching strap, and do you collaborate to ensure that they have complementary or contiguous design motifs?

I always make a concept of the composition, and Akiko and Eiko do their work along with it. Eiko starts making the strap after Akiko finishes doing the inlays and coloring. Wood inlays are Akiko’s “language,” and embroidery is Eiko’s language. I’m so lucky to have their expertise.

Describe your building process for us—from initial concepts to prototyping, building, finishing, etc.

I don’t make plans or templates. Every time I start building a guitar I draw the outline directly on the wood. Besides a drill press and band saw, all of our tools are handheld.

Fellow luthier Akiko Oda polishes the binding on a Jersey Girl double-neck.

Do you have “standard” or preferred body shapes in your head that you typically work from, or is it “anything goes”?

I primarily do single-cuts, but I always adjust it a little bit, depending on whether it has a tremolo or what pickup arrangement it has. I also work in different scales, so the shape and layout changes a bit every time. I mostly do 25" scale, but sometimes I’ll do 24 3/4" or 25 1/2". I also work in my own scales—like 641 mm [25.24"]—to help it balance better. Bridge placement is very important, so sometimes I want to put the bridge a little bit closer to the neck. That can really affect the bass response and how well the guitar resonates.

How long does one instrument typically take to build from start to finish?

Well, let me answer this way: This year we’re trying to make 15 compositions. Most years it’s between 10 and 13.

Do you have specific preferences/favorites for wood and other materials?

We’ve never actually ordered specific woods. We have a great wood supplier who’s been helping us for a long time. He works with all the big Japanese guitar factories, like Fugijen, and sometimes he has ash or alder with very fine grains and figuring that the big factories working on, say, a Telecaster don’t want. He sends materials he thinks will be useful for us. Then I design each guitar based on the weight of the wood. I have to think a different way based on whether it’s heavy or light.

What about hardware?

We’ve been using Gotoh hardware on all our guitars for a long time.

What’s the range of prices for your instruments?

Our guitars cost between $7,000 and $10,000. Boston Guitar is my main distributor in the U.S., but I also sell direct at jerseygirlhg.com.

“Chichitoko” (Japanese for “father and son”) is a double-neck featuring a mandolin on top and a 12-string on bottom.

Let’s talk about some specific instruments. Crow on a Scarecrow looks like a fascinating cross between an archtop and a flattop, especially with that interesting soundhole pickup.

That was our first archtop. We wanted to try to make it a very special-sounding one and use our dinosaur bracing and unique construction. It has a pickup mounted in the neck block rather than on the top.

Which the pedal is it paired with?

That’s our Middranger, which allows you to alter the mids without adding overdrive. It’s my favorite pedal.

Takutack is incredibly thin, and it’s paired with a 3-knob pedal with no labels and no footswitch.

Takutack is our first composition with a middle board—the soundboard that the bridge is mounted to is actually inside the guitar. You can see it through the f-holes. I wanted to make an archtop without having to make bent sides—and also make it very light. Takutack has an arched top and back, so it’s loud enough to enjoy by yourself without electronics—I always want my guitars to be fun to play. That’s crucial. But it also has a magnetic pickup and contact pickups inside. The pedal is a preamp mixer for all that.

What’s the story with the Chichitoko double neck?

“Chichitoko” means “father and son” in Japanese. We used to make a double-neck line called Rainmaker for a long time. The total theme of that composition is “Peace. We all are in the same box called Earth.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)