| Hear the Techniques Click here to download an example track using these orchestration techniques. Guitars: Guild F-50, Guild D-66, Guild F-412NT, Ibanez AW, and '70 Fender Precision strung up with flatwounds. Acoustic mics include Earthworks QTC1, Earthworks OM1, DPA 4099G, through an Earthworks 1024 and a Focusrite ISA 428. Strings by David Henry, recorded in Nashville. |

From Beethoven to Page

Although Wikipedia isn’t necessarily the best place to turn for life answers, sometimes it hits the right notes, so to speak. And in this case, its definition of “orchestration” isn’t bad: “Orchestration is the study or practice of writing music for an orchestra (or, more loosely, for any musical ensemble) or of adapting for orchestra music composed for another medium. It only gradually over the course of music history came to be regarded as a compositional art in itself.” That windy explanation expectedly hints at its use in an orchestra, but it also mentions that the writing can be applied to any music ensemble. It can be anything—from a simple acoustic-guitar duet to the hardest, heaviest detuned metal tunes. But understanding the layers of orchestration can also help with production and mixing of recorded music.

Before we talk about orchestrating guitar parts, let’s step back for a basic look at the tradition of orchestration. The term orchestra is from the Greek name for an area in front of a performance stage that’s reserved for a chorus. Orchestration itself is the practice of writing melody, harmony, and arrangements for various instruments that date back to the earliest ensembles. The job of an orchestrator and/or composer was to decide which instruments played which notes—and with what sort of dynamics—in every measure of a composition. Ensembles started out small but grew through the centuries into chambers and then into full-blown orchestras and symphonies of 80 or more pieces with strings, woodwinds, brass, and percussion. Add in a full choir, and you could be composing for well over 100 people. That’s a lot of writing. That’s a lot of orchestration.

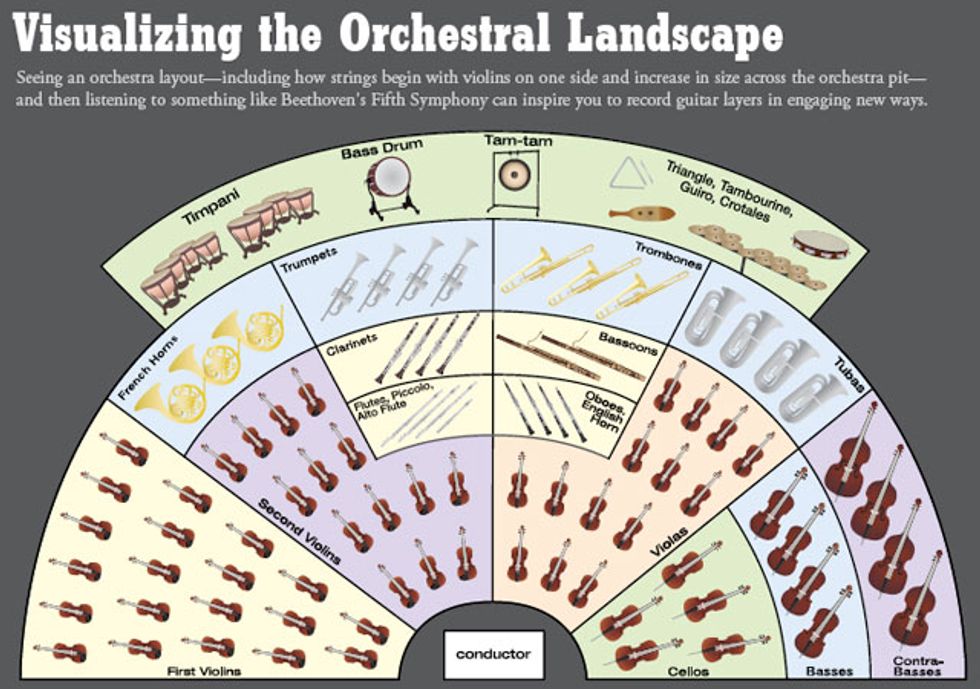

Take a look at the layout of a typical modern orchestra in the image below. Notice the way the strings are laid out from left to right—first violins, second violins, violas, and cellos. The basses (usually called “contrabasses” or “double basses”) sit behind or to the side of the cellos. The woodwinds (flutes, oboes, clarinets, and bassoons) sit behind the strings. Then you have the brass (French horns, trumpets, trombones, and tubas), followed by the percussion instruments (timpanis, snares, bass drums, and cymbals) positioned at the rear.

With this in mind, think about how many times you’ve heard Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. Listen to a good recording of it with headphones (the London Symphony Orchestra’s is my favorite) while you’re looking at the diagram above. Listen to how those powerful string lines seamlessly interweave with the brass, woodwinds, and timpani. In his orchestration, Beethoven wrote string lines that move quickly from section to section—from violins to violas to cellos to basses. These parts literally pan themselves in the stereo field simply based on how the various instrument sections are placed on the stage. This is the art of production in action hundreds of years before recording-console panning knobs were invented!

Now think about the fact that most of the instruments Beethoven worked with could play only one note at a time. We guitarists are lucky to be able to play chords on a single instrument. That means we have the option of approaching our instruments like orchestral string sections—we’ve got bass (like an orchestra’s basses and cellos), mids (violas and second violins), and treble (first violins). When you think of your guitar like that, you realize that the various strings and octaves can be used to layer and orchestrate powerful guitar parts.

Early guitar orchestration in the ’60s was often recorded with multiple players performing their parts live in the same room. Back then, engineers didn’t have the capability to record so many tracks of layered guitar, so they recorded everyone at once. With the advent of 8-, 16-, and 24-track recording, vast vistas were opened to guitarists looking to explore orchestration in the studio. Brian May’s work with Queen is a great example of this. Now, with digital audio workstations (DAWs)—not to mention all the plug-ins available to help you layer different tones—we have almost unlimited ways to experiment.

A great example of this is how Jimmy Page layered his parts in the classic Zeppelin cut “Ten Years Gone.” The song starts out with a single guitar in the left speaker, with a bit of plate-style reverb in the right. Then the bass plays along in the center until the second guitar part appears in the right speaker playing a lower octave than the first part. Then it breaks back down to the single guitar in the left speaker again. Throughout the song, various guitar parts come in and out at different pan positions—sometimes in mono, sometimes in stereo. Some parts play octaves of each other, and some play harmonies. By the end of the song, you can hear at least six guitar parts intertwining with each other, covering lows, mids, and highs. It’s a fine example of studio production and guitar orchestration.

Simulating a String Section

One reason string sections sound so rich is that when several musicians play the same line—as they do in an orchestra—subtle differences in intonation, timing, and bowing thicken and enhance the sound. And, of course, each instrument produces unique overtones and timbres that enrich the music.

|

Capo Tricks

But you don’t need a roomful of guitars to generate ear-grabbing overtones. Used creatively, a humble capo can be a powerful tool. Essentially, you can use it to dramatically change your guitar’s scale length and natural resonance.

For example, first play through a chord progression in the lowest positions, using open strings whenever possible. This gives you the rich, full sound of long, vibrating strings. Record this, and then clamp a capo in the middle of the neck—between the 3rd and 7th frets, depending on the key—and work out the progression in this new position. As you navigate the changes, the strings will be shorter and sound tighter and brighter, and the chord fingerings and voicings will be different. If you include open strings, they’ll fall in different places than in the original track. Using a lighter pick on this capoed part will brighten the sound even more. Two tracks of chords may be enough, but for an even bigger sound you can place the capo around the 10th or 12th frets and work out yet a third variation of the changes.

Using this capo trick, you’ll have many unison notes played on different strings. Though the pitches will be the same, these notes will have different timbral qualities, thanks to the variations in string gauge and length. And when you layer guitar parts using a capo the way we’re discussing, you’ll also be introducing some chord tones an octave (or two) higher, which adds sparkle to the ensemble sound.

High-Strung and Baritone Guitars

You can get a similar effect by playing a progression or line on a high-strung guitar. To convert a standard guitar to a high-strung axe, simply replace strings 6-4 with the E, A, D, and G octave strings from a 12-string set. The B and high-E strings (2 and 1) remain the same. This is also known as Nashville tuning. A high-strung guitar adds the jangle of a 12-string without its burly bass and low mids.

But maybe you want more bottom end. Using a baritone guitar—a long-scale 6-string that’s tuned a fourth or fifth below standard guitar—you can often double a line an octave lower and thus emphasize it the way a cello player might. But unlike a cello, you can also play chords on a baritone, and this opens up a world of harmonic possibilities in the lower registers.

Orchestrating with the Space Ace

When I worked with Ace Frehley on his last solo record, Anomaly, he cut an instrumental song called “Fractured Quantum” that was a continuation of the song “Fractured Mirror” from his first solo album. It’s another good example of studio guitar orchestration. It begins with a single guitar panned slightly left. It’s followed by a 12-string part playing an identical line on the right. Then more layers are added as a single electric melody starts to take shape. By the outro, eight or more guitar parts can be heard weaving around each other. At the end, it breaks back down to a fade-out on a single guitar.

While we were cutting many of these tracks with engineer Alex Salzman, Ace would grab any number of guitars—from old Les Pauls to Strats, Teles, and acoustics. He also used one of my high-strung guitars, along with 6- and 12-string acoustics, and even a doubleneck. Then we recorded different guitars through different amps for a variety of tones. A lot of the electric parts were played through a Vox AC15 right in the control room.

Although Ace had a clear direction in mind, he also spent a lot of time experimenting up and down the neck to see which guitar parts layered well with each other. The different tonal ranges of each guitar, along with various amps, also helped create unique colors in the song.

Make the Most of Multi-Tracking and Education

I’ve worked with several different teachers to develop orchestration skills, and I still feel like I’ve just scratched the surface. It can be difficult and challenging, but the time spent studying and learning has truly helped my composition ability—and my guitar work. Now, whenever I work in the studio on other people’s tracks or my own, I think about how different layers could help me create interesting parts.

For example, I cut a piece on my last record that was simply an experiment in guitar orchestration. (You can get away with this when you don’t care about “moving units.”) I wanted to write a song that layered various forms of acoustic guitar like a classical composer would with strings sections, but I also wanted to include real strings.

I started with a line played on a high-strung guitar. Under that, I played bass lines on a jumbo Guild F-50 acoustic. Together, they sounded like one guitar. In the second verse, I played an old Fender P bass (strung with flatwounds) to add deeper bass to the initial tracks. In the bridge, I had the violins, viola, and cello (recorded by David Henry in Nashville) play the melody around the guitars. At this point, the guitars now included a doubled 12-string panned hard left and right to make room for the strings—both sonically and production-wise. I let the real strings take the solos (panned as they would be on an orchestral stage), and then I mixed in layers of high-strung, 6-string, and 12-string guitars, along with tempo-mapped delays. Each guitar part and each guitar type was carefully chosen to add specific tones and frequencies to the production.

Orchestration studies have also helped me with mixing and production skills. To emulate the sectioned-off nature of instruments in an orchestra, I break songs down into layers, such as lows, low mids, mids, high mids, and highs. Each instrument gets placed on the “stage,” or the stereo field. I separate the instruments and parts using both EQ and panning, and I think about what listeners will hear from a production point of view.

Here’s what I mean by thinking about it from a production point of view: Put on a pair of headphones and listen to a few well-produced pieces of your favorite music. Focus on the specific tones and frequencies of each instrument and where it sits in the mix. Listen to how the layers of sound are formed.

There’s a lot to learn by just listening to the production and orchestration of great music. Take what you like, discard what you don’t like, and then apply it to your own recordings. Use your home studio to experiment with various techniques you hear being used successfully by others. Also, consider taking time to study basic orchestration principles with a teacher or on your own. It’s worth the time and effort.

Producer Steve Skinner on Orchestrating Guitar

Producer/arranger/programmer Steve

Skinner is an industry veteran whose

credits include Chaka Kahn, Spyro Gyra,

Celine Dion, Lionel Hampton, and

many more. He was also lucky enough

to work closely with legendary producer

Arif Mardin (Queen, Norah Jones,

Jewel) for over 15 years. I sat down with

Skinner recently for a few quick thoughts

on both traditional and guitar-specific

orchestration.

Producer/arranger/programmer Steve

Skinner is an industry veteran whose

credits include Chaka Kahn, Spyro Gyra,

Celine Dion, Lionel Hampton, and

many more. He was also lucky enough

to work closely with legendary producer

Arif Mardin (Queen, Norah Jones,

Jewel) for over 15 years. I sat down with

Skinner recently for a few quick thoughts

on both traditional and guitar-specific

orchestration.What’s one of your favorite guitar orchestrations?

Smokey Robinson’s “Second That Emotion.” There are three different guitar parts from three different players. The only other accompaniment I can hear is brass, bass, and drums. Each guitar player stakes out his own tonal area—backbeat chords, a low-midrange funk line, and high-midrange chords—and stays there. None of them gets in the way of the others.

Guitar players, because they can play chords, tend to think vertically—a chord followed by a chord, followed by a chord. Orchestrators and orchestra writers think horizontally about melodies that interweave, and if they happen to form chords, so be it. Groups like Interpol do some amazing things with counterpoint in their guitar and bass lines, which sometimes have a quasi-random feel to them—like one player went to one note and the other went to another note, and they said, “Yeah, I like it!”

How about a favorite classical orchestration?

In terms of creating colors with interesting combinations of instruments, my absolute favorite is Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. From the very beginning— where the bassoon is playing at the very top of its range—Stravinsky uses instruments in unusual pairings and brilliant chord clusters. For countermelodies, I love the second movement of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony. The melody itself is very plain—it’s the countermelodies that give it movement and emotion. For counterpoint, I like Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings. If you look at the score, it’s deceptively simple—parts moving up and down by scale steps, mostly in one key—but somehow the emotional impact is huge.

What did you learn about orchestration from your years working with Arif Mardin?

Never bump into the vocalist’s note. I once got a wrist slap for doing that. You can follow along with a vocalist, but in your countermelody don’t have some of your notes hit their notes and then go away. You either go right along with it, or stay away from it. It’s best to have your countermelodies work around the vocal.

With strings in particular—especially if you’re orchestrating with guitars—you can get away with a lot more dissonance than you’d think. The song “Iris” by the Goo Goo Dolls is a great example: The guitar is playing a big B chord and the strings are majorly dissonant, but it really works. Some of that is from basic counterpoint rules, like the one about not having two parts simultaneously jump to a dissonance, like a second or ninth. Instead, have one line sustain and move the other line up or down into the dissonance. Then move away from it again. It helps to study those dry old counterpoint rules—I find myself using them constantly.

Are there any books or websites you recommend guitarists check out to learn those counterpoint rules—and any other important lessons about orchestration?

The book I go to most often is The Technique of Orchestration by Kent Kennan. I have the 2nd edition, from 1972, which is still available. There is also an updated version that comes with a CD. If you’re interested in studying counterpoint, both Kennan and Walter Piston have excellent books. I’d also recommend finding and studying scores of pieces you like. Following the individual parts, while listening to how everything fits together, will change how you hear music.

What to Listen for in Orchestrated Guitar Tunes

Curious about the extents to which you can orchestrate with 4-, 6-, and 12-strings? With guitar-specific tunes, listen and try to ascertain the following:

• How many guitar parts are there?

• Are some of the melodies or progressions doubled, tripled, or multi-tracked even more than that?

• Are the guitars playing octaves, unison lines, or harmonies?

• Are the parts in stereo or mono?

• Where are the guitar tracks panned, and at what level are they mixed?

• Are there effects such as reverb and delay—and where are those effects panned?

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)