It’s Friday night and Gary Clark Jr. is relaxing in a downtown New York bar, calmly sipping a beer while everything around him is in chaos. Hard rock blares from the sound system behind him, a motorcycle roars by in the street, and yet it’s barely audible over the din of the next table, where an after-work foursome has just burst into a full-throated paroxysm of laughter. Unfazed, the 28-year-old guitar hero actually seems bemused by the cacophony, as though it’s all just part of the whirlwind journey he’s been on for the last few years, but one that really began back in his hometown of Austin, Texas, when he was still just a lanky teenager.

“I don’t think I’d be doing what I’m doing now if I hadn’t grown up there,” he says, thoughtfully stroking his chin. “As a kid, I used to just walk down Sixth Street and I fell into it—the vibe, the culture, the influence, the music. And when I first started on the music scene, I fell in with the blues. That was the only place that I knew of where I could get up on the stage and play with perfect strangers and make something happen. From there, I learned about Clifford Antone and Antone’s club. That whole scene definitely set up a solid foundation for me.”

Which might be putting it mildly. Clark has already been widely touted as the hottest singer- guitarist to emerge from Texas since Stevie Ray Vaughan and Billy Gibbons. In some quarters, he’s even referred to as “the savior of the blues.” But he doesn’t seem overwhelmed by the accolades— in fact, let’s tell it like it is: The blues are just part of what makes up Clark’s sprawling repertoire. Armed with his trusty cherry red Epiphone Casino and his road-battered Fender Vibro- King, he can ignite an explosive riff like “Bright Lights,” the title cut from last year’s teaser EP, and reel off choice licks like Hubert Sumlin on the “Killing Floor.” Or he can dial back the mood to the introspective vibes of “Things Are Changin’,” channeling the sweet guitar melodies of Curtis Mayfield and the soulful tenderness of singers like R. Kelly and Raphael Saadiq. You might not know it from his hard-rocking stage show, but Clark is a modern chameleon of musical styles.

“A friend of mine called me musically schizophrenic,” he quips with a chuckle. “I’ve even been asked if I was confused. But it got to this point where I was sitting around with all these demos that I’d recorded on my own. I hadn’t really played them for anybody, and they weren’t straight-ahead blues at all. They were just in my head, things that were haunting me. It’s like you gotta get ’em out—I figure what the hell, it’s just music, you know? It would be torture for me to hold that inside and not just let it out. So that’s what happened, and all this stuff ended up on one album.”

That album is the longawaited Blak and Blu, coproduced by Clark with hip-hop icon and bassist Mike Elizondo and rock impresario Rob Cavallo. It started off, Elizondo recalls, as a mission to capture what Clark did live—as heard in songs like the snarling “Numb,” which simulates a rocket from the heart of the British second wave—but evolved to include more complexly arranged and programmed songs like “Blak and Blu,” a funky D’Angelo-ish departure into neo-soul.

“He’s not a one-trick pony,” Elizondo insists. “That’s what I think is most exciting about Gary’s debut. He’s an incredible guitar player, but he’s also a true songwriter and a visionary. He sees himself as an artist who can have no boundaries, and I think he’s proven that. We didn’t have to stick to one particular sound, so we could veer off into a couple of different areas. Gary is the glue for songs like ‘Blak and Blu’ to work seamlessly with the ones like ‘Numb’ and ‘When My Train Pulls In.’ It’s all because his vocals and his guitar playing pull everything together.”

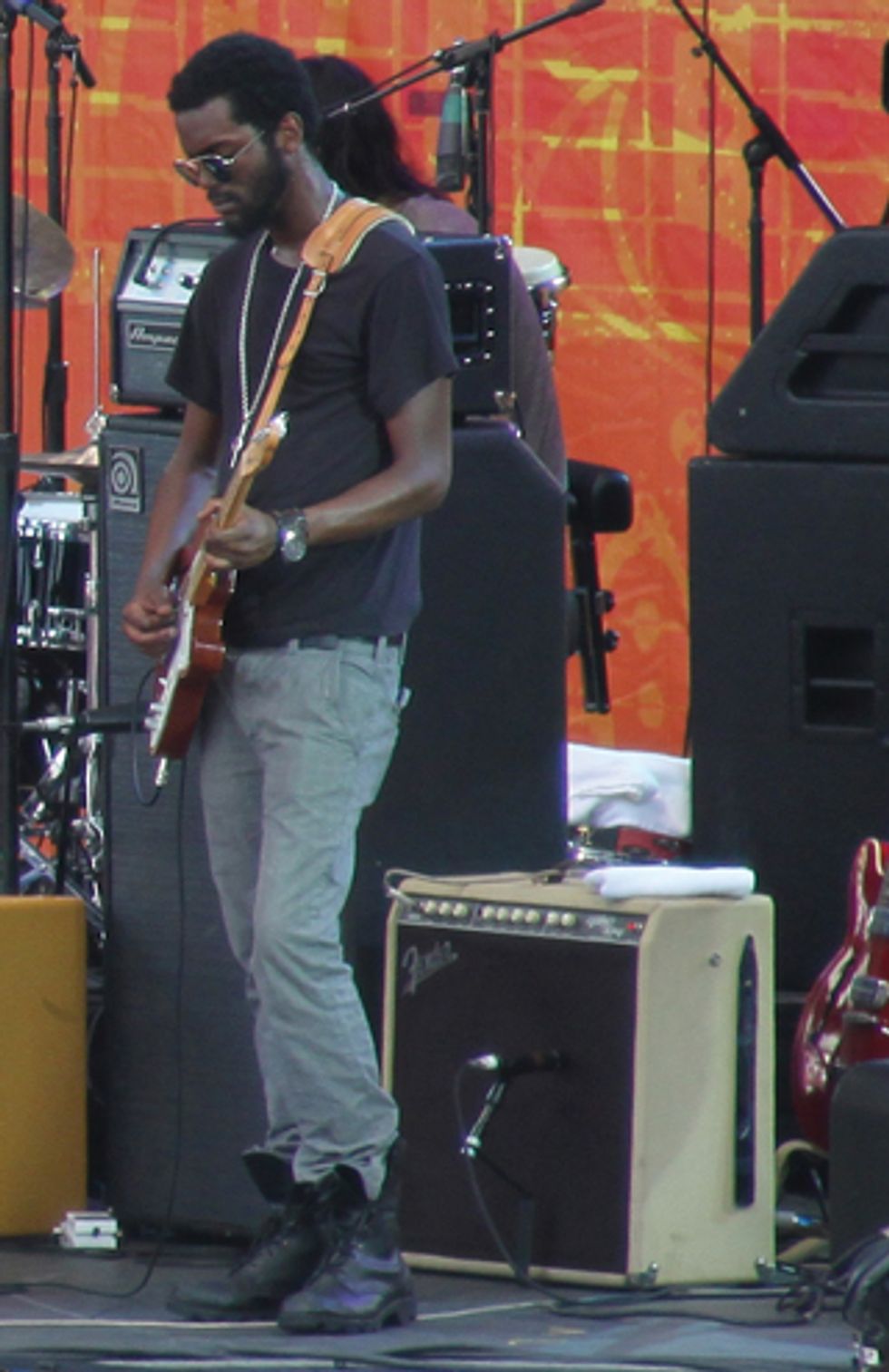

Of course, some comparisons are more obvious. Clark has been covering Jimi Hendrix’s “Third Stone from the Sun” for quite a while now. On Blak and Blu, he folds his quirky, one-chord psychedelic fugue arrangement of the song into a medley with “If You Love Me Like You Say,” made famous by Albert Collins. Clark isn’t quite the pyrotechnical genius that Hendrix was (at least, not yet), but it can’t be lost on the few still alive who knew Jimi personally that the two guitarists share a laid-back, shy, almost aloof demeanor—a stark contrast to their take-no-prisoners delivery on stage. Jimmie Vaughan must have sensed it when he first caught Clark’s show at Antone’s (and subsequently struck up a friendship with him), and Eric Clapton must have felt a twinge of nostalgia for the days of Swinging London when he booked Clark for the 2010 Crossroads Festival—a date which, arguably more than any other, sealed Clark’s acknowledgement by the heavyweights, including the legendary Buddy Guy.

Beyond the hype, though, at a time when revivalism—in the hands of such artists as Jack White, the Black Keys, Alabama Shakes, and many more—has become the driving force in rock, Clark brings something unusually fresh to the picture. He can conjure up the Mississippi Delta or the electric church with equal authenticity, but he also folds his many influences, from hiphop to silky soul, into his sound with a natural ease that can’t be taught, let alone faked. Maybe it comes from spending most of his adolescence woodshedding with his parents’ records and anything else he could lay his ears on—including Nirvana, the Ramones, the Beatles, and everything in between. Whatever it is, it’s Gary Clark Jr.’s moment, and there’s nowhere else to go but up.

Mike Elizondo: Tracking Blak and Blu

Context is everything, and for Mike Elizondo, it seemed more than logical that the best way to capture Gary Clark Jr. in the studio was to get an extended taste of what he does onstage. “I actually just tagged along with him and the band for three or four shows on the West Coast leg of his tour,” he explains. “It was great, not only for me to see him play night after night, but also for the down time. We got to hang and talk about music and his vision for the record. I got a deeper sense of what he wanted to do, just by talking about music and talking about concepts. That really gave us a great head start.”

For about 10 days, Elizondo and Clark huddled up for preproduction at Can-Am Studios, tucked away in the residential Southern California town of Tarzana. They went through everything that was finished and unfinished, riffs and songs, to get a feel for how the album would take shape. When they were ready for drummer J.J. Johnson, Elizondo took up his bass and the three of them set up to play live in the studio. Clark camped out in an iso booth so he could record vocals and play guitar (with his amp powered up and mic’ed in another room), but he had a line of sight to Elizondo and Johnson so the “live feel” wouldn’t get lost. “Numb” was the first song on the docket.

“My own personal concept was to go for Jimi’s live version of ‘Voodoo Chile,’” Elizondo says, referring to the classic Side A closer of Hendrix’s Electric Ladyland. “They’re in the studio with Stevie Winwood, and Jack Casady on bass and Mitch Mitchell on drums, and they’re all playing live—I think Jimi actually had an audience in the studio to capture that feeling. I remember the first time I heard that song, it just felt like you were in the studio with them, and so I wanted to try and capture that space, not only of the performance, but the space in the studio, to get as much of a live feel from the performance as possible.”

Clark played Elizondo’s ’68 Gibson ES-335 on “Numb,” plugged in through a Prescription Electronics Experience pedal and overdriven to the max. There’s even a bit of microphonic interference on the front end of Clark’s signal, just as the song begins, that everyone decided was worth keeping. “I think it sets up this feeling of anticipation,” Elizondo says. “It’s like ‘What’s about to come out of these speakers?’ That’s him just kicking on the pedal, and us waiting for him to start it off. It just seemed like we should keep it as an intro, rather than clean it up.”

For quieter moments like the album closer “Next Door Neighbor Blues,” Clark opted for a late-’50s Gibson acoustic, a lone kick drum and an inexpensive room mic to get an oldschool Alan Lomax-style blues sound. “Gary told me about how he used to do these gigs where it was just him playing a bass drum and playing guitar and singing all at once,” Elizondo explains. “It made perfect sense to do ‘Next Door Neighbor Blues’ like that, all in one take. It was all part of trying to make the album feel raw and a little bit lo-fi and not too over-the-top. That was tricky on ‘The Life’ and ‘Blak and Blu’—the songs that are closer to pop—but I think we found a great balance. Gary is an artist who truly knows who he is, what he stands for, and what he’s going for, and I was just really impressed by that.”

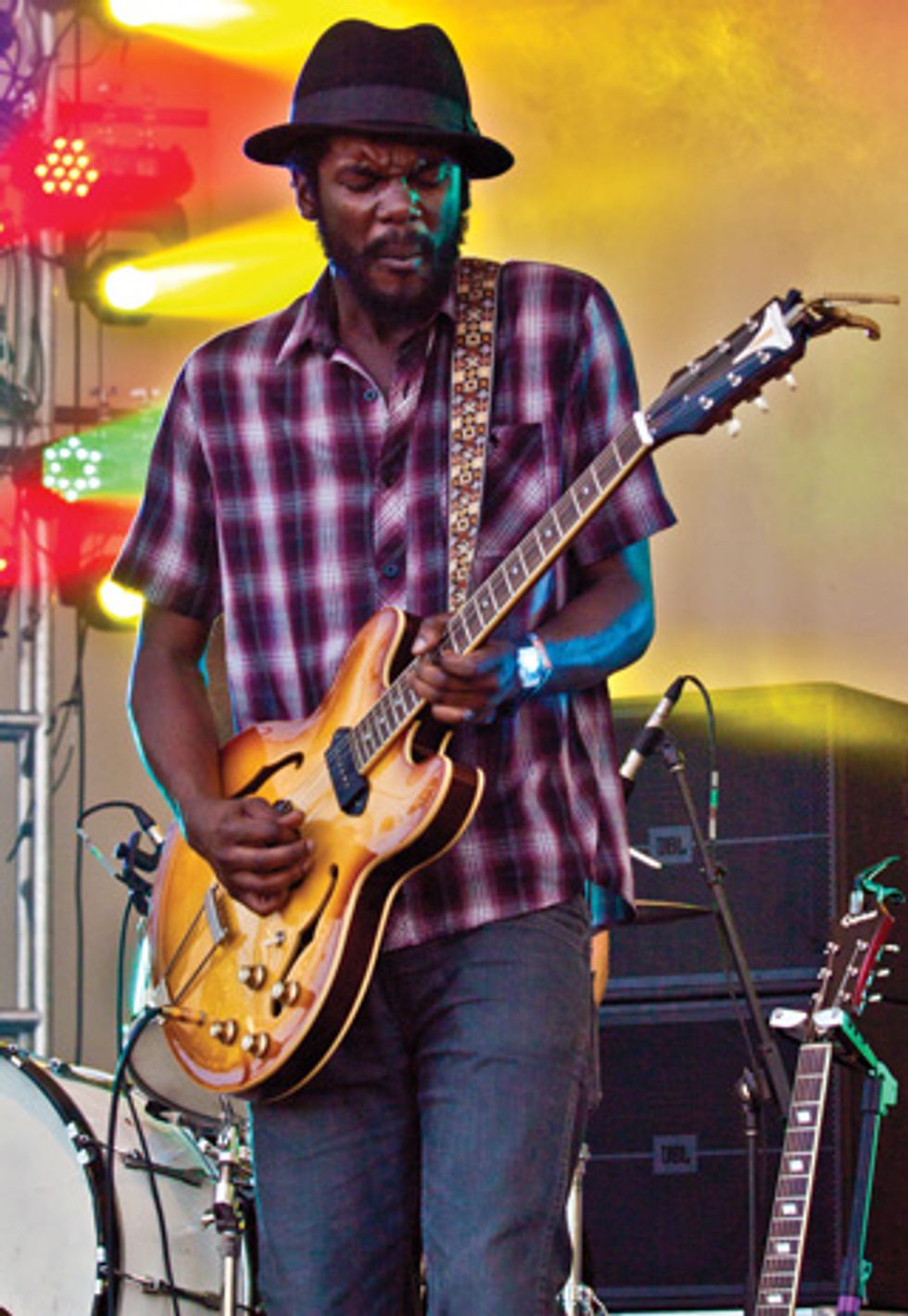

Clark playing a sunburst version of his favorite guitar, the Epiphone Casino, on “Please Come Home” at Lollapalooza 2012 in Chicago’s Grant Park. Photo by Chris Kies

These days you’ve got a pretty

killer band behind you when

you’re on the road—Eric Zapata

[guitar], Johnny Bradley [bass],

and Johnny Radelat [drums]—

but in a way you’ve also been

your own band, right?

That started when I moved out

of my parents’ house and got my

own apartment. Instead of buying

furniture, I bought drums

and an 8-track recorder and keyboards

and turntables—anything

musical, that’s what I wanted.

I just started collecting instruments.

I had two roommates

who were going to college, so

they would go to school all day

and I would sit there and bang

around. And right around when

I was 19, I started to get really

familiar with what was going on

in my head, and then hearing it

back on tape, and trying to lay

that down and translate it. It all

started to make sense then.

When did you first feel like

you were getting your own

sound together and doing your

own thing as a guitar player?

It’s definitely an ongoing process,

but I think when I was around

20 or so is when it really started

coming together. I was recording

my own stuff outside of the blues

“genre,” I guess. That’s when I

quit covering T-Bone Walker

and Freddie King and all that. I

strayed away from straight-ahead

blues for a while, and started

getting into people like Shuggie

Otis and Cody Chesnutt. [Otis’]

Inspiration Information changed

my whole perspective on what

you could do with the guitar.

That whole psychedelic thing was

funky and raw, cool and soulful,

and just very outside the box.

It comes from Curtis Mayfield too, definitely, but basically it got to the point where I said, “Okay, I can get through fine on lead, so let’s play some rhythm guitar now,” you know? You can play a lead for 25 minutes, but it’s a different thing to get that timing and tone and feel and groove going. So it’s an ongoing process.

What was your first guitar?

It was an Ibanez RX20. It has

two humbuckers, black with

the white pickguard, and a

maple neck. I wanted the “Little

Wing” tone right away. I didn’t

understand why, and, of course,

a little bit later I was like, “Well,

you need a Stratocaster.” I got

one eventually and I still have

it—it’s actually an American

Squier. This guy came to a show

at Joe’s Generic Bar down on

Sixth Street in Austin. I was

maybe 15, and he says, “I’m

gonna send you something—

give me your address.” And

sure enough he sends me this

American Squier Strat! I think

it’s an ’89 or a ’90, whenever

they were making them here.

Funny you should mention

“Little Wing,” because of its

connection to Jimi Hendrix

and Stevie Ray Vaughan. How

did you first discover them?

Well, a friend of mine down the

street heard that I was playing

guitar, and one day he was like,

“Check this out,” and he gave me

The Ultimate Experience CD. It’s

the green and purple one with

Jimi on the cover, and he’s standing

there with a cool military

jacket and scarf—really trippedout.

So I got back home and put

it on the headphones first, and

that changed everything. I’d never

heard anything like that really.

It was crazy. He definitely takes

you to a different place mentally.

I’d never heard sounds or lyrics

or chords like that before—the

tension, the resolution, the

mind-bending—from the first

few songs, it completely flipped a

switch. I felt like I’d been missing

something for a long time.

And along with that Hendrix CD, I got Texas Flood the same day. I mean, you can’t really play anywhere in Austin without Stevie Ray Vaughan being part of the conversation. He’s just so major. You can’t pick up a guitar as a kid in Austin and not know his music—at least, I think that. If it’s not that way, it should be. He’s so influential. Stevie and his brother Jimmie, and Derek O’Brien, too—the list goes on. When you’re in Austin, these are the people whose music you have to know.

Gary Clark Jr. sat in with several artists at the Crossroads Guitar Festival in 2010, including with the man himself, Mr. Eric Clapton. Photo by Chris Kies

What was it about Jimi’s

“Third Stone from the Sun” in

particular that pulled you in?

I was just drawn into it—the spoken

dialogue, the sound effects,

the slap-back delay, and the whole

spaceship-landing thing. It was

one of the coolest things I’d ever

heard in my life, so it always

stuck with me. Playing it just

came from us jamming around

town—I think it was Jay Moeller

[drums] and James Bullard

[bass] with me at the time. I’d

just go into something and they

followed, and over the years it

turned into what we do now.

And, in fact, a lot of the way we play is based on just seeing how things go. That’s always been a fun way to experiment, and onstage you get that energy sometimes. It can be really great, or sometimes people look at you like, “What the hell are you doing?” And that’s how you know. That’s how I started to engage with what’s really going on out there. Years and years of trial and error have gotten us to where we are at this point.

How did you first get hold of

the Epiphone Casino?

I was guitar shopping with my

friend [Eric] Zapata, who plays

guitar in the band. I think I just

really wanted a hollowbody. And

I like the P-90s—the sound and

the look of them—so I just came

to the conclusion that I wanted

a Casino. We rode around town

and ended up at this spot, and I

was looking at the natural ones.

Zapata said, “Try the red one!”

and I was like, “No man—that’s

a bit bold, don’t you think?” And

he was like, “Just try it, man—

that’s the one!” Sure enough I

plugged it in, A/B’d them—the

natural and the cherry red—and

the cherry was just screaming at

me like, “You know I’m the shit.

I’m the one!” When I got back

to the house and plugged it into

my rig, it was like I’d just been

waiting for that sound.

What is it about the tone of

those P-90s that really packs

a punch?

Well, you can flip it on the

neck and it’s dark, round, and

bold. It’s really slick and sexy if

you want to go there, and you

can get that treble in the bridge

if you want a bite. The range

is just so broad. It’s the most

versatile axe I’ve ever picked

up, and it’s light, so it won’t

break my back. And it might be

annoying at points, but I love

how it feeds back when you

crank it up. It’s also fun to sit

there unplugged and just play. It

has a great tone and resonance.

Are there players who have

played that particular guitar

that may have inspired you to

pick it up? Didn’t Otis Rush

play a Casino, for example?

Yeah, and I think he also played

the Epiphone Riviera. Have you

ever seen the American Folk

Blues Festival footage? He plays

“I Can’t Quit You Baby”—just

some lowdown blues on the

Epiphone. That’s so sick. I think

I want one of those. And later

on, you know, the Beatles recorded

with the Casino. They made

some okay records too [laughs].

But also I just like the look of it.

It’s just a beauty to look at.

What’s your main amp

these days?

Lately I’ve been using a Fender

Vibro-King. Zapata gave me my

first one, and he’s the one who

got me to jump in with both

feet on the whole hollowbody

thing, so a lot of that’s from him.

There’s just something about the

three speakers in the Vibro-King

that got me. It breaks up just

enough at the right volume. It’s

crunchy but it can be real sweet

to you, and the reverb on it is

killer—the vibrato, too.

You’ve got a few pedals in

your arsenal, too.

I’ve got a Fulltone Octafuzz and

a Real McCoy wah-wah, and

I’ve got a couple of Analog Man

pedals—an Astro Tone Fuzz

and their new [ARDX20] delay.

Zapata kind of snuck that one

on my rig. It has the expression

pedal, too, so you can adjust

the time of the sweep. I think

those options can help express

certain feelings and certain

attitudes, and I’m always looking

for new ways to do that. It’s

exciting because there’s so much

out there that I don’t even

know about—the whole thing’s

an adventure.

What was it like working

with Mike Elizondo and Rob

Cavallo on Blak and Blu?

It’s been very new to me. Rob’s

got the aggressive, loud, harder

sounds on the album. “Numb”

was actually with Mike, but

on “Bright Lights,” that was

with Rob. And he’s all about

guitars—loud and fast. When

it comes to Mike, he can really

relate on grooves and textures—

soulful R&B stuff. He’s got that

from playing bass with Dr. Dre.

So he had an understanding

of where I come from, but it

was broad and diverse, as far as

points of view were concerned.

Our heads were all in it together.

I learned a lot from making

this record, and I had to let go

of a lot of stuff, too.

For the basic tracks on

“Numb,” you and Mike and

J.J. Johnson all played together

live as a power trio, right?

Yeah. We were all in the room

at Can-Am [Studios] in Tarzana

[California]. It was great. Mike

has everything—Pro Reverbs,

AC30s, Marshalls—he had all

kinds of amps. I think there

were two or three fuzz pedals on

that song, too. Mike was on his

hands and knees like, “Check

this one out! Check that out!”

But I’ve really gotta give it up

to him. I don’t think I really

knew that he was so into guitar

tones. It was definitely like

being a bunch of little kids putting

Legos together!

Gary Clark Jr.'s Gear

Guitars

Epiphone Casino,

Gibson ES-335,

Gibson acoustics

Amps

Fender Vibro-King

Effects

Fulltone Octafuzz,

Real McCoy wah-wah,

Analog Man Astro

Tone Fuzz, Analog Man

ARDX20 delay, Prescription

Electronics

Experience pedal (on

the album)

So who are you listening to now?

Otis Redding, Parliament—actually

I just got this Eddie Hazel

record yesterday. I haven’t really

explored Eddie Hazel as I should,

but from what I’ve heard so far,

he’s just doing some fierce, powerful,

psychedelic guitar playing.

It’s some funky-heavy blues—I

mean, my dad played that stuff

all the time. But I’m doing a

little research on him, so I’ll get

back to you on that.

I’ve been listening to stuff that’s all over the place though. I mean, I’ve been riding around in a van for a few months with a bunch of dudes, so we’ll put on anything from hip-hop stuff to Little Dragon to Radiohead to Bob Marley and the Wailers, Nina Simone—a lot of different things, man. With all the music, I’m just trying to soak it up and let it go. I try not to think about it too much, and just let it happen and have fun, you know?

YouTube It

Witness Gary Clark Jr. perform guitar gymnastics with his

Epiphone Casino that would make Jimi proud.

With Tommy Sims on bass, Clark wows the big

players with “Bright Lights” at Crossroads 2010.

The effects are on full throttle on this fuzz-filled

track that includes a medley from Hendrix’s

“Third Stone from the Sun.”

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)