Photos by Shervin Lainez

At 16, Joanne Shaw Taylor started turning heads with her smoky vocals, gutsy guitar riffs, and snarling solos. The English guitarist first emerged playing feral Tele in one of Dave Stewart’s post-Eurythmics bands called D.U.P., and it wasn’t long before Taylor made her solo debut with 2009’s White Sugar. At the 2010 Blues Music Awards, she earned Best New Artist Debut for that album, which she quickly followed with 2010’s Diamonds in the Dirt. At the 2011 British Blues Awards, Taylor scored two more prestigious honors—Best Female Vocalist and Songwriter of the Year—for “Same As It Never Was,” a song from Diamonds in the Dirt.

For her latest solo album, Almost Always Never, the 26-year-old decided to head in a new direction. Rather than return to Memphis to work with Jim Gaines [Eric Johnson, Carlos Santana, John Lee Hooker, Buddy Guy, Stevie Ray Vaughan], the legendary producer behind her first two discs, Taylor enlisted Mike McCarthy and tracked in his Austin studio with a band he assembled for the occasion. As a result, Almost Always Never has less to do with Stevie Ray and Albert Collins—two of Taylor’s blues influences—and instead offers a more exploratory vibe with extended solos, deep grooves, and experimental tones.

We asked Taylor to take us through this musical transition and describe the creative process that birthed Almost Always Never.

This album is a departure from your

previous two releases. Instead of blues-based

rock, you take a more experimental

approach—even exploring psychedelic

jam-band territory. What drew you in

this direction?

Two things made this one different. First

off, I had more time to make the record. For

both White Sugar and Diamonds in the Dirt,

I had a 10-day window to write the songs

and another 10 days to record them. So

those albums came together very quickly.

But last summer I got a series of ear

infections that left me temporarily deaf and

unable to perform, so I was essentially stranded

where I was staying in Houston, and I

had a bunch more time to write songs for the

new album. I’d never had this opportunity

before. Once I’d written what I thought was

an album the label wanted to hear, I still had

a lot more time, so I wrote another batch of

songs. Some for myself, some for other artists—all kinds of stuff. When it finally came

time to start the new album, I bit the bullet

and went sod it, I’ll send over all the songs

and see which ones get picked.

The second major difference was that we used a different producer this time. I’d always worked with Jim Gaines, who I actually love and adore. But this time we decided to shake things up a little bit—more for me, you know, to force me into a challenging situation. Mike McCarthy produced Almost Always Never, and that accounts for the different musical approach. I’m the sort of person who gets very comfortable and doesn’t like change, so the idea of having someone new to work with who I didn’t know was quite terrifying, to be honest.

How did you connect with him?

It was one of those lucky things, really. I

like to be involved in that kind of stuff—I’m a little bit of a control freak—so my

manager suggested Mike. I Googled him

and saw his resume, which includes Spoon,

And You Will Know Us by the Trail of

Dead, and Patty Griffin. I thought, you

know what? That’s right up my street, in

that those are some of my favorite artists

and that’s the kind of music I listen to. But

it’s not generally what I want to sound like,

and that I found very intriguing.

He’s based in Austin, so when we had a gig there, I drove over to his studio one afternoon and checked it out. He’s a very quirky guy—I’m sure he was British in a previous life—and we just hit it off. Mike is from a totally different school than me, but we also had things in common. He’s a big Jimmy Page fan and he likes some of the classic British rock I grew up with. I saw we had enough in common to make it work and enough not in common to make it interesting. It turned out well and was a really good experience for me.

Did he select the other musicians?

Yes, he brought in studio guys he regularly

uses—[drummer] J.J. Johnson, [bassist and

slide guitarist] Billy White, and [keyboardist]

David Garza. Fortunately, I knew of

all these musicians and was a huge fan of

their playing. In fact, I was so impressed

with their careers I got quite nervous about

going into the studio.

Describe the tracking process and how it

compared to White Sugar and Diamonds

in the Dirt.

On the previous albums, the goal was to

capture live drums and bass. I’d jam along

to show them the changes, but I’d redo all

my guitar parts later. This time we actually

cut all of my rhythm playing and even

some of my vocals live with the band over

the course of three days. On “Jealousy” and

most of “Standing to Fall,” we had such a

vibe going live in the studio that when we

tried to redo the guitar solo and vocal, it

didn’t match the atmosphere we captured

when the band was there. So we kept those

as live takes. I played in the same room as

J.J. and Billy, and David was in a separate

keyboard room.

How did working with a keyboard player

affect your rhythm playing and soloing?

That was another different thing about this

record. I’ve had a trio for a long while, so it

was a brand new experience working with a

keyboard player of David’s caliber. Having

not worked with many keyboard players,

I didn’t know what he was going to do.

Give us an example.

Mike would come in and go, “Joanne, I

know everyone else thinks it’s great, but

you’re playing too much.” [Laughs.] I hate

to admit it, but that was the situation. I’m

used to working with a three-piece, so I’m

trying to be Jimi Hendrix over here, but

when you’ve got a keyboard player, you

don’t need that.

The last track on the album, “Lose Myself to Loving You,” I wrote as a ballad, and there was a gap in the middle we’d left open for the token guitar solo. But once we’d tracked the song, we all agreed that a big, wailing Eddie Van Halen guitar solo could ruin it. David’s piano was so beautiful, it completed the song as far as I was concerned, so we left it alone and let the piano show through. It was really nice to treat a song as more than an excuse for a guitar solo.

Did Mike hear the songs you were

hoping to include on the album before

you went into the studio?

Yes, I’m kind of the queen of Garage

Band, and I just demo everything out. I

put the bass down myself, along with all

the guitar parts and vocals. When Mike

and I first got together, I did my usual

thing of giving him my Garage Band

demos, so he and the band could know

how I was hearing the music. He got

back to me and said, “Yeah, that’s not

what I want. I just want you and a guitar

in a room.” And I panicked because

I’d never done that before—to be honest,

it scared me senseless.

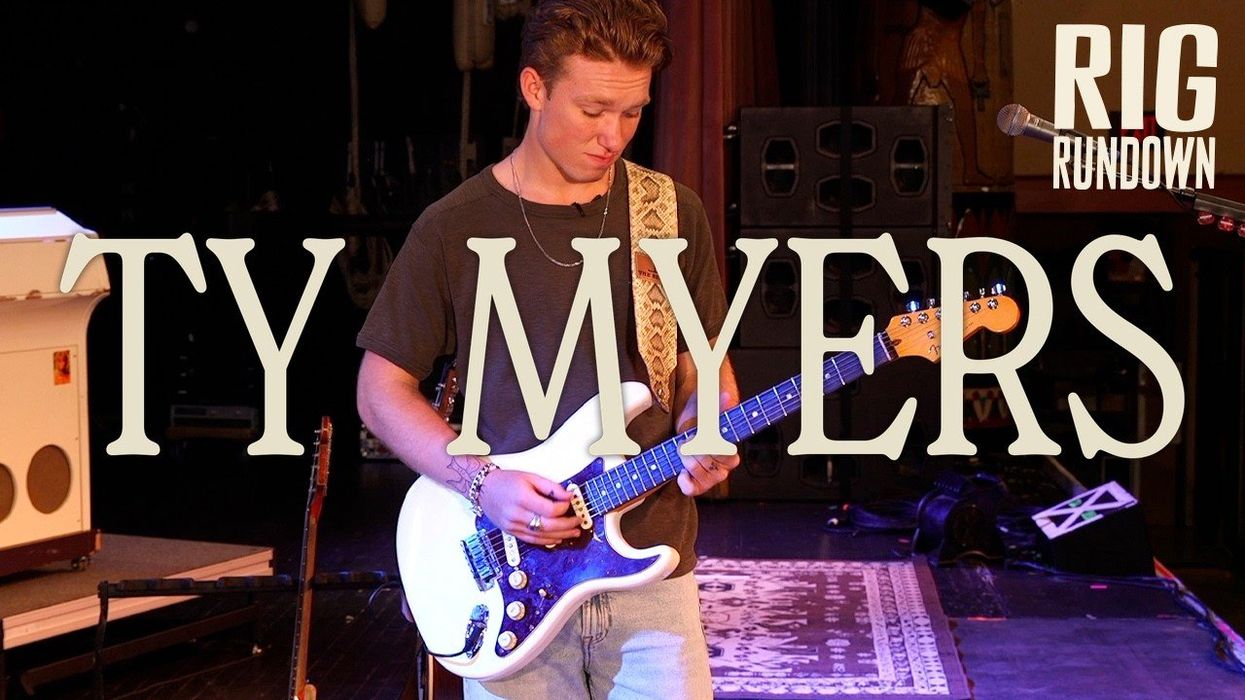

JoAnne Shaw Taylor has a blast onstage with a recentvintage Fender Strat. Photo by Rob Stanley

Why?

I wasn’t sure if I was a good enough

writer that the songs would stand by

themselves if I didn’t have all the instruments

on them. But he seemed to think

so. So I just recorded them in the hotel

room with me playing guitar and singing

over the top.

How many songs did you give him

to listen to?

I think I ended up sending Mike about

20 songs, and we cut 12 of them. But

the odd thing was, three of them I

wrote in the hotel the night before we

went into the studio—“Tied & Bound,”

“Lose Myself to Loving You,” and

“Beautifully Broken.”

You wrote three songs the night before

the session?

Yeah, but I wouldn’t advise that to anyone.

The one thing I know about myself

is that I tend to come up with songs at

the last minute. As soon as the pressure

is off because I know we’ve got enough

material for the album, I quickly add

new songs to the list. For White Sugar,

I wrote three songs on the plane on the

way over to Jim’s [Gaines] house. It’s almost

to the point where my producer should lie

to me and tell me the sessions are scheduled

a week before we really begin.

How can you even remember three songs

you’d written the night before?

It was a bit of a challenge. When we got in

there, everyone was looking at me because

I didn’t know the changes very well. I had

to keep telling them, “Come on, I just

wrote this last night.”

Compared to your previous two albums,

the songs on Almost Always Never seem

to unfold at their own pace and offer you

more time to explore the fretboard.

When I was forced, for health reasons, to

have this time off last summer, I reverted to

being my 13-year-old self and just played

guitar every day. This period allowed me to

get excited about guitar again. I know this

sounds terrible, but when you’re a professional

guitarist playing 200 dates a year,

you can lose sight of what got you started.

When I was 13 in my bedroom looking at

posters of all my idols, I’d pretend I was

them. And I got that feeling again. When I

went in the studio this time I had a bunch

of new licks and was really excited to mess

around with new tones.

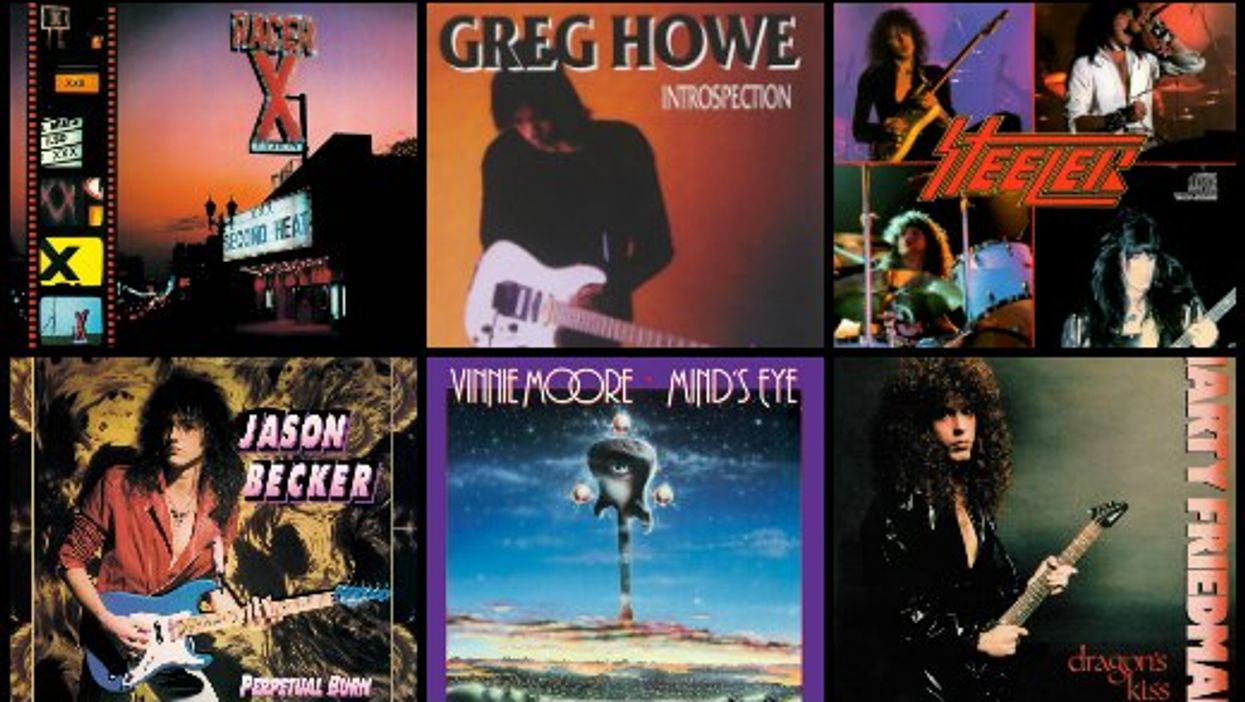

So there were some fresh influences on the album, but more to the point, there were old influences I’d dug up again. I took a trip down memory lane and spent a lot of time listening to guys like Eric Johnson, Richie Kotzen, Paul Gilbert, and Gary Moore. In terms of bands, I went through a big King’s X phase around that time. It seems odd to me now, given how the record turned out—not like King’s X—but that was what I was listening to ... very guitar-based rock.

You’re pictured with a Les Paul on the new

album and while there are some Fender

sounds on the tracks, many of your solos

and riffs have a fatter tone than before.

Did you switch from your Tele to a Les

Paul for a lot of these guitar parts?

I did. Some folks at Gibson had heard my

music and they lent us a Les Paul for the

recording. It was perfect timing—I was

playing new material with a new producer

and a new band, so why not try a new

guitar? I absolutely fell in love with the Les

Paul they loaned me, but unfortunately

they wouldn’t let me keep it. And being

female, I’m pretty sure once they told me

I couldn’t have it, that’s when I decided I

wanted it. [Laughs.]

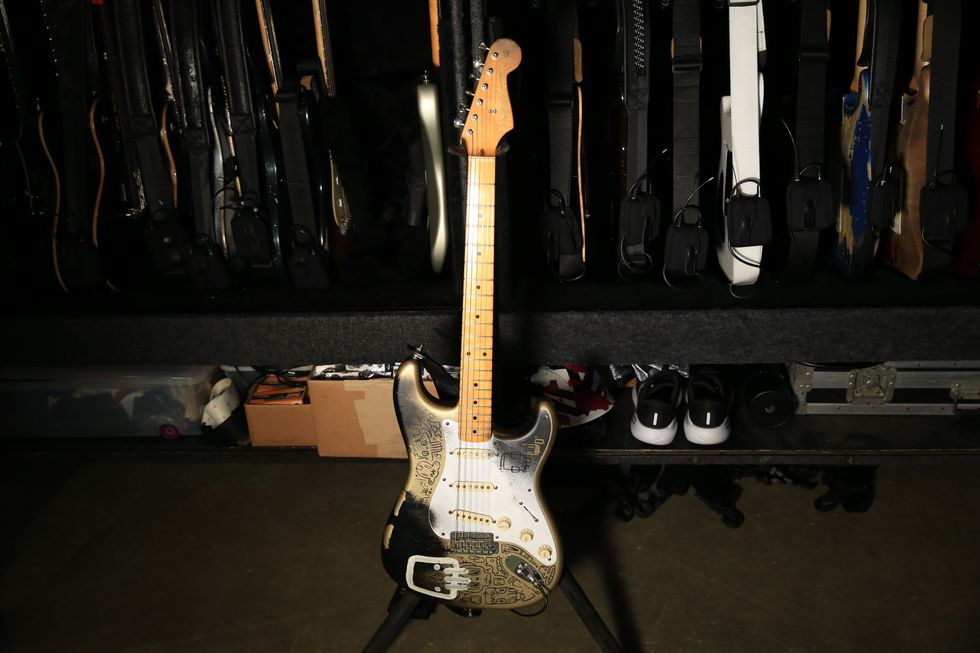

Taylor says her mother wasn’t too pleased that her teenage daughter played an Esquire with a pinup girl on it, but she softened a bit when Taylor played a gig with Annie Lennox for the Queen. Photo by Rob Stanley

Did you also try a different amp?

Yes. Though Billy [White] played bass on

the album, his main instrument is guitar.

He played with Don Dokken and in

Watchtower, and he’s kind of a shred god.

Anyway, he brought in his ’72 Marshall

50-watt head and 2x12 for me. At that

point, with everything else being new and

different, I thought, “Why not? Let’s go

for a different sound.” The funny thing

was, although I was going for Eric Johnson

and Gary Moore, I think I still ended up

sounding like me.

I have no qualms telling you I fell in love with that Marshall, and I’m hell-bent on getting one. A ’72 50-watt Marshall is really the holy grail—you put a nice Les Paul through it ... well, it’s perfect.

Any other amps?

Mike had an old ’60s Silvertone we used

a lot for the rhythm. That and Billy’s

Marshall for lead were the two main ones I

used for everything. We had both amps in

a separate room—a big space at the back

of the studio. I could just about hear the

Marshall from where we were situated, so

I’m pretty sure it was on 11.

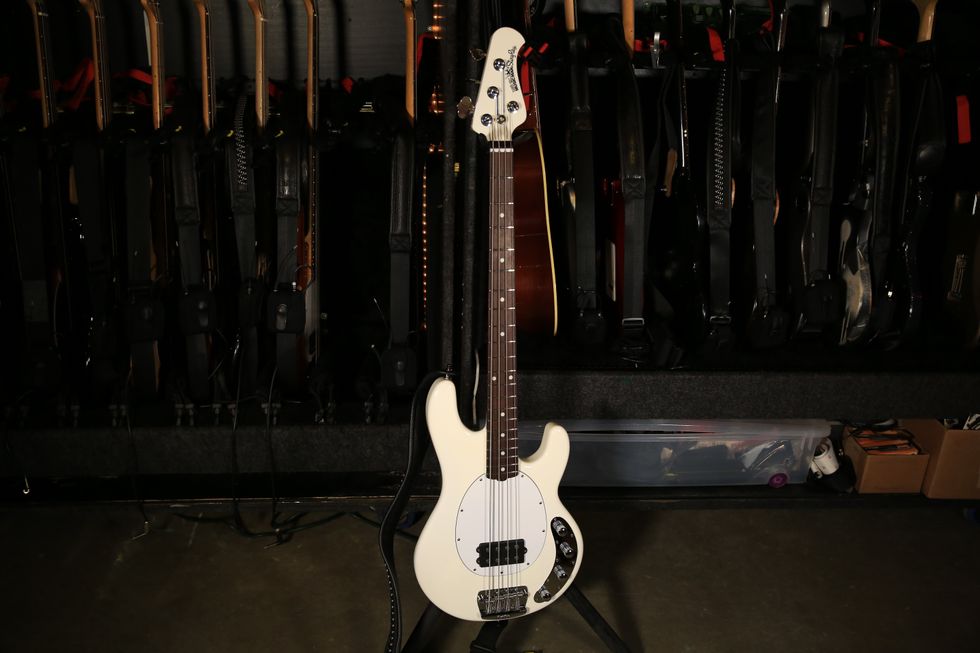

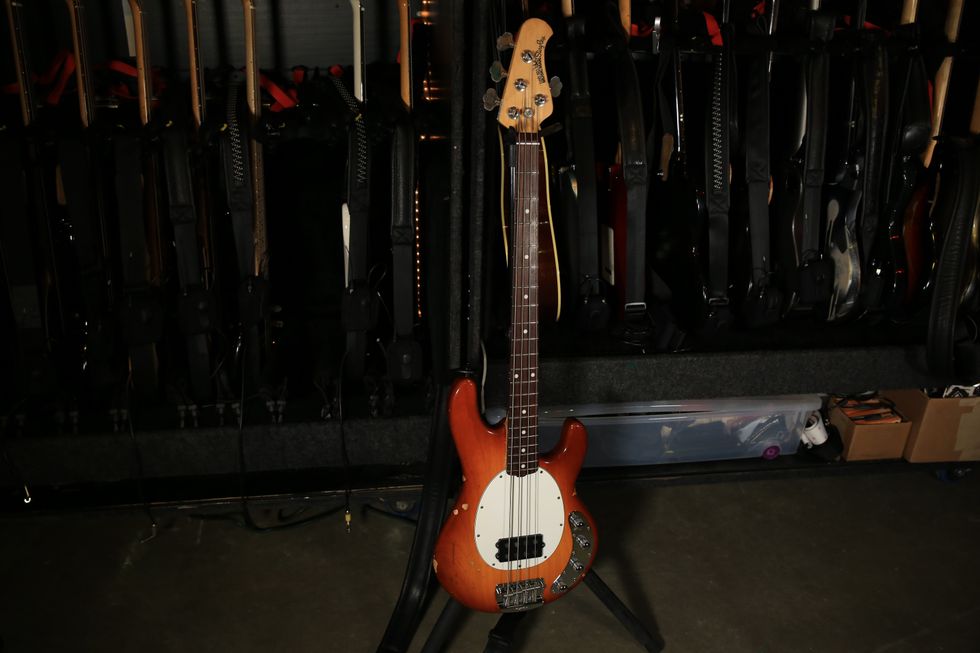

Is that a Stratocaster on “Lose Myself ”?

Actually that’s a Music Man. My boyfriend

has a fine array of guitars and I stole it

from him. It has a nice glassy tone that just

seemed to work on that track. We used

Mike’s Harmony Master—a 1960s hollowbody—

a lot. I used a bunch of different

stuff I’d never used before, whether just

from not being comfortable with a piece

of equipment or feeling there were rules I

shouldn’t break. I think I only picked up

the Telecaster once or twice, which was

quite fun in a way—a busman’s holiday.

What sort of rules are you referring to?

Well, I didn’t want to upset fans who know

me as a Tele player. But then I realized the

sound is really in your hands, and there’s

no harm in trying to inspire yourself with

a new instrument or go for a slightly different

tone. That was a fun lesson to learn.

Did you use an octave fuzz on the solo

in “Soul Station”?

I did. Mike had a bunch of toys, so it

was a time of experimentation. That

octave fuzz is a Death By Audio pedal

called the Octave Clang, which I love.

When we cut that track Mike said,

“What are you thinking of for the solo?”

After hearing what J.J. did on the drums,

I said, “I pretty much want it to sound

like guitarmageddon.” He handed me the

Octave Clang and told me to plug it in.

After a few notes I said, “Yeah, that’s it.”

What about other effects?

Mike had an old Rat distortion pedal I

used for “Maybe Tomorrow,” which has

probably the weirdest solo on the album.

We had a vintage Boss chorus pedal, a vintage

MXR chorus pedal, and a Dimebag

Darrell wah-wah—my favorite wah—

hooked up for that. “Maybe Tomorrow”

was interesting because I wrote it as a very

up-tempo rock song and the lyrics were

completely different. I took it to Mike and

he said, “That’s not working for me.”

Joanne Shaw Taylor thwacks a 4th-string G while soloing on one of her Strats at a 2011 gig in Bilston, U.K. Photo by Rob Stanley

Ouch.

Yeah, exactly. So we got in with the band

and Mike said, “J.J., what are you thinking

of on this?” And J.J. slowed it down a

lot and made it into what it is—that kind

of Dr. John voodoo groove. It sounded

really good, but the lyrics didn’t fit with

the music anymore, so we left that to the

very last minute. As we were finishing up

recording, I wrote new lyrics that would

fit the new feel. At that point, the whole

song became a sort of improvisation. I

put down that riff and thought, okay,

what else can we add to it?

Out of all the songs, that was the one where we really didn’t know where we were headed. We just built it up by listening and seeing where it wanted to go. Mike had hooked up a Roland Space Echo and was making these weird sounds, and I basically decided I was going to play a couple of phrases and then intersperse strange noises from the Space Echo. We just went for some weird stuff, which was good fun. That song was very produced. Mike chopped and pasted guitar solos, and that makes it more of a piece than a guitar solo. It’s a jam song, all about the vibe.

“Army of One” sounds like you guys

were all just jamming in a circle around

a couple of mics.

We were, except we didn’t have the luxury of

a couple of mics. I think we had one. When

I wrote that song, I thought it was going to

sound like “Going Home” off the first record

and “Dead and Gone” off the second. Because

I have this fetish about writing traditional

blues lines I want to make modern, I always

write these evil blues songs I’d want to hear

in an episode of The Sopranos. Like you’re

driving through the city late at night and

you’ve got a body in your trunk. [Laughs.]

So this was another song like that, but Mike said, “Let’s make it acoustic.” And I said, “Really?” It was the last song we cut. We all went out together to dinner that last night and had a glass or two of wine, and then stopped by the liquor store on the way back to the studio and bought some tequila.

I see where this is going.

We all sat in this one little room. J.J. is on

the marching drum, Billy is playing slide,

David is on the mandolin, and then there’s

me on a hollowbody. Mike came into the

room—he’s the one you hear at the beginning

of the song telling us what the tempo

is because we’d all gotten so excited and

unruly we weren’t quite doing the job.

He had to come straighten you out.

Exactly! Dad had to come in and ruin the

fun. But we did the song in one take. It was

very organic, very last minute—a late-night

studio bonding experience. That song is one

of my favorites for sentimental reasons.

Taylor bought her ‘66 Esquire on London’s historic Denmark Street when she was 15, and had a Seymour Duncan Jazz SH-2 placed in the neck. Photo by Rob Stanley

What guitar were you playing?

The hollowbody Harmony through a tiny little

amp—some 5-watt model Mike picked up

in Japan. We had it cranked but it just wasn’t

putting out. Most people think it’s a resonator,

actually. Half the time I tell them it’s not and

half the time I let them believe it is because I

don’t want to correct people. [Laughs.] That

guitar ended up fitting the song quite well.

I don’t think it sounds like an out-and-out

electric. It’s a welcome break on the album,

and I’ve never done an acoustic track before.

Tell us about the gear you use onstage.

I have my two staple guitars. One is a 1966

Esquire, which I’ve had for years and years—it’s my first guitar. When I was 15, I bought

it in London on Denmark Street [a historic

stretch of road known for its music shops

and recording studios]. At the time I was real

scared that my dad was going to beat the hell

out of me for taking a train down to London

at 15 and buying a ridiculously expensive

guitar with all my pocket money. But I got

it cheap because the previous owner had

attacked it with a knife. It had a gaping hole

near the neck, so I had a guitar tech dig it

out and add a humbucker there. That made

it kind of my dream Telecaster.

What humbucker?

A Seymour Duncan Jazz [SH-2].

Is this Esquire your guitar with the pinup

girl on it? And if so, did you put that on

or was that from the previous owner?

Yeah, that’s the one, and I added the pinup girl.

My mother wasn’t very happy with that—in

fact, she was a little worried. You know how

moms are: “Why is my daughter putting a

picture of a pinup girl on her guitar? And why

is she playing guitar anyway?” Try being 15 and

attempting to explain to your mom why there’s

a half-naked lady on your guitar. It wasn’t

her favorite part of my youth, but she’s used

to it now. Moms just don’t get rock ’n’ roll,

that’s what I’ve learned, but I think the Annie

Lennox gig soothed mom’s issues. [In June

2012, Taylor played lead guitar in Lennox’s

band for a huge televised Diamond Jubilee

Concert in London honoring the Queen.]

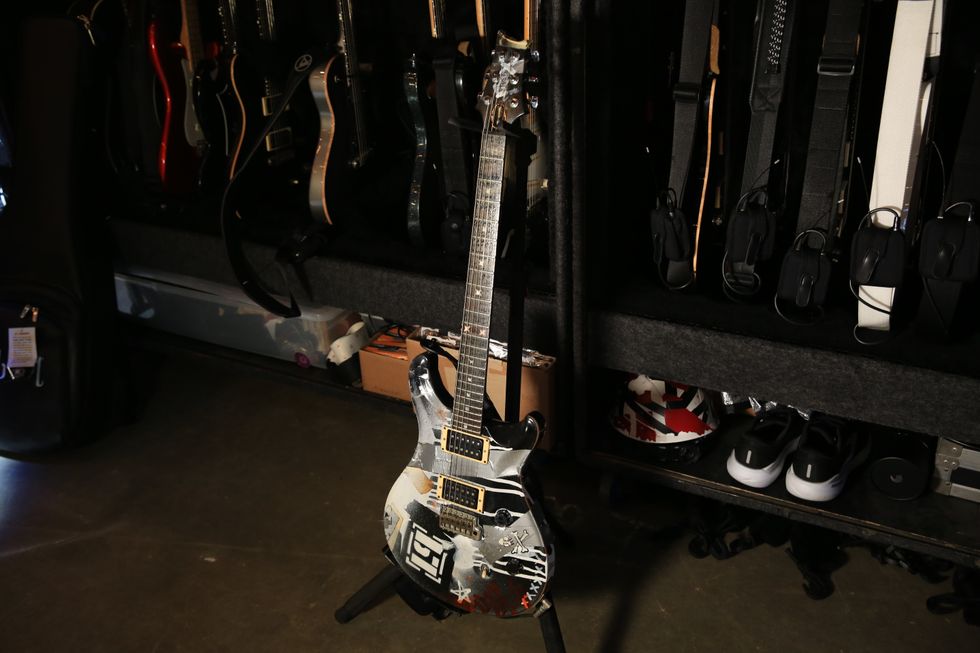

Then there’s my Dave Stewart Telecaster, which I’ve had on permanent loan for a decade. It has a Warmoth Tele body, which has a belly cut like a Strat, and a ’55 Fender maple neck. That guitar is so heavy, it sounds like a cross between a Tele and Les Paul.

I’ve seen recent photos of you onstage

with a Les Paul.

Yeah, that’s a new addition. It’s a 2008

Custom Shop model. A little bit lighter

than most—about nine pounds—with a

’60s neck. With my teeny, tiny girl hands,

I can’t play the big ol’ ’50s baseball-bat Les

Paul necks.

Those are my main three guitars. I’ve got a bunch of odds and sods, the kinds of things I go into pawnshops to find. They’re dirt cheap and I like them. I’ve got a Squier 51—Fender’s answer to a Telecaster/Strat hybrid—that’s worth about 100 bucks. I installed a Seymour Duncan Pearly Gates and pimped it out a little bit. Also a ’92 Tele and an ’88 Tele, which are both pawnshop finds, and then a couple of standard Strats, including one my grandmother bought me. They’re pretty standard, though I’ve replaced the pickups in most of them.

And stage amps?

Live, I’ve been using a Louis Electric

KR-12 combo and a ’65 Bassman head

driving a 2x12 Marshall cab with standard

Celestion Greenback speakers. The

Bassman has been modded to ’62 specs,

and I use it for clean rhythm sounds like

on “Beautifully Broken,” “Lose Myself to

Loving You,” and “Diamonds in the Dirt.”

I’ve always been a huge fan of Bassmans. I

love the ’62 cream Tolex Bassmans—I just

think there’s nothing more beautiful. Even

if I ever have a child, I think I’d find the

Bassman more beautiful.

What does your pedalboard look like?

At the beginning of this year, I decided to

strip down my pedalboard. I’m a typical

guitar player, so I’ve gone through a bunch

of phases. I’ve had a pedalboard the size of a

Hammond B3, and it’s not fun to tour with

and lug around. So now I play through a

little board. I keep one in Australia, one

here in the U.S., and one in Europe, and

they’re all pretty much carbon copies.

I use three pedals from Mojo Hand FX—a Recoil Delay, a Colossus Fuzz, and a Rook Overdrive, which has replaced my Tube Screamer. Other than that, I have a Way Huge Aqua Puss delay, which I use for slapback, and an MXR Dyna Comp, one of the old models. These pedals give me pretty much everything I need. I’ve also added a Death By Audio Octave Clang for the solo on “Soul Station.” Between the amps and different guitars, five or six pedals are all I need to get the tones I want. How about strings and picks? I’m a devoted fan of Ernie Ball strings— always have been. I use the Skinny Top Heavy Bottom sets, gauged .010–.052. I tune down a half-step—mostly for my voice, because I have a slightly lower register— and I used to play with .011s. But then I grew up and realized I have female hands and I’d have to stop playing in 10 years if I continued using big-boy strings. I don’t have Jimi Hendrix’s hands!

I’ve just started using the Dunlop Eric Johnson signature picks, the little jazz picks. I find those plectrums really help with righthand control. It’s not so much for speed, but for making sure the notes ring nicely.

Joanne Shaw Taylor’s Gear

Guitars

Customized 1966 Fender Esquire,

Warmoth T-style with ’55 Fender

Telecaster maple neck, 2008

Gibson Custom Shop Les Paul,

Fender Squier 51, various production

Fender Stratocasters

Amps

’65 Fender Bassman head

and 2x12 Marshall cab with

Celestion Greenback speakers,

Louis Electric KR-12

Effects

MXR Dyna Comp, Way Huge

Aqua Puss delay, Death By Audio

Octave Clang, and Mojo Hand FX

Recoil, Colossus, and Rook

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball Skinny Top Heavy

Bottom sets, Eric Johnson

Classic Jazz III picks

In the liner notes for Almost Always

Never, you’re credited with all electric

guitars and vocals, as well as playing

something called Gordon on “Piece of

the Sky” and “Lose Myself to Loving

You.” What’s that?

Well, there’s some background to this

story. Mike puts his name on everything—every microphone has “property of Mike

McCarthy” on it, for example. When I took

that first studio tour, I looked around and

thought, okay, that’s the sign of a control

freak. After I got to know Mike I teased

him about it, saying it was like a child

going to school for the first time and his

mom puts his name in his underpants.

Fortunately he took it well.

One day when Mike and I were going over the songs before the band came in, he said, “I’ve seen this 1960s Gibson acoustic in Guitar Center and I want to buy it. The only problem is, the previous owner was obviously a kid and he put giant orange letters on it to spell out his name. It’s a beautiful ’60s Gibson with these really gross, plastic letters spelling Gordon.” I said, “Well, buy it anyway.” And the next day he brings that guitar in.

Do you know what model Gibson?

I think it was a J-45. So that’s what I played

on those two songs. It was just funny that

he found his dream acoustic guitar and

some kid had put his name across it in

giant orange letters. Karma. So Gordon is

just an acoustic guitar, but you have to call

it by its proper name.

YouTube It

To experience Taylor’s fretboard prowess, check out the following clips on YouTube:

Taylor tears into two songs from

White Sugar in a 2011 London show.

In another song from White Sugar,

Taylor pulls a sweet range of clean

and dirty tones from her Squier ’51 at

a festival in Wilmington, Delaware.

Annie Lennox features Taylor on lead

guitar at a massive 2012 outdoor

concert at Buckingham Palace in

London. Dig JST’s white outfit and

angel wings! And, of course, her Les

Paul and extended solo.

Miller’s Collings runs into a Grace Design ALiX preamp, which helps him fine-tune his EQ and level out pickups with varying output when he switches instruments. For reverb, sometimes he’ll tap the

Miller’s Collings runs into a Grace Design ALiX preamp, which helps him fine-tune his EQ and level out pickups with varying output when he switches instruments. For reverb, sometimes he’ll tap the