Photo by Larry DiMarzio

Steve Vai first gained notoriety nearly three decades ago when he joined forces with David Lee Roth after the famous frontman’s split with Van Halen. Almost immediately, Vai usurped Eddie Van Halen’s throne as the king of rock guitar, and throughout the subsequent decades Vai’s continual innovations have distinctly changed the sound of rock guitar. What has always significantly differentiated Vai from other virtuosi in the annals of rock history is that, although he can burn with reckless abandon and fire, he’s also an academic at heart—a passionate player whose mastery of music theory, composition, and orchestration could rival a Julliard professor. While still in high school, Vai wrote his first orchestral piece, an arrangement he called “Sweet Wind from Orange County.” Soon after, he landed a gig with Frank Zappa by sending him a transcription of Zappa’s impossibly difficult piece “The Black Page.”

But even after decades of reigning as one of the world’s most formidable guitar icons, Vai continues to hone his skills as a modern classical composer. In fact, he doesn’t even need a guitar to satiate his musical urges. In some cases, a pencil and manuscript paper are all the man needs. Releases such as 2004’s Piano Reductions Vol. 1 feature strictly piano arrangements of Vai’s compositions (performed by frequent collaborator Mike Keneally), and just this past November Vai premiered an orchestral composition sans guitar entitled “The Middle of Everywhere” that was performed by the Noord Nederlands Orkest (North Netherlands Orchestra). Of course, he has also indulged his inner guitar geek by not only writing for but also performing live with the Metropole Orchestra on releases like 2007’s double-live album Sound Theories Vol. I & II.

For a lot of guitarists, an album like Sound Theories would be their magnum opus—after all, how do you top something as grand as writing for and performing with a symphony orchestra? But not for Vai. His latest release, The Story of Light, is the second installment of a rock-opera trilogy that began with 2005’s Real Illusions: Reflections. As you’d expect, Story of Light is much more than just an instrumental shred fest—it features Vai’s trademark genre-busting arrangements and an unlikely cast of guests, ranging from a gospel choir to vocalists Aimee Mann and (The Voice finalist) Beverly McClellan.

We caught up with Vai to talk about his latest epic, his take on the new Van Halen album, and whether he’d still be content if he were just a mailman rather than a guitar hero.

What’s the concept behind Story of Light?

It’s sort of like a rock opera. I hate using

that term, because I don’t like opera at all,

but basically it’s the second installment of

the Real Illusions trilogy. My plan was to do

this story, and then at the end I would take

all of these records and kind of amalgamate

them into the story—and then, maybe,

the songs would be put in proper order and

there would be new stuff.

If somebody picked up Story of Light before

Real Illusions, would the context be lost?

They’re not in a sequential, chronological,

linear order. It’s not the kind of record

where you have to follow the concept and

know the story in order to enjoy the music.

I wanted it, first and foremost, to be enjoyable

music. Then if you read deeper into it,

each song tells a little piece of the story.

The Story of Light spans a variety of

styles. Does having such a broad range

make it harder to unify things across

the three albums?

What I’m setting out to do is just do what I

really like to hear in music, which is to create

diversity—but with unique dimensions to it.

“Creamsicle Sunset,” for instance, is a clean

guitar sound and a simple piece of music.

Then you listen to something like “The Book

of the Seven Seals,” which is like “contrast”

with a capital C. A lot of people are comfortable

making records that have a musical

theme that’s in every single song. It’s like,

“Okay, this is our 7th string and we’re tuning

down and we’ve got a lot of distortion. We’re

going to do some soft parts now and then …

but this is us.” You could listen to song number

one and song number 10, and it would

sound like the same band. That’s what a lot

of people do, and that’s great, but there’s no

rule that you have to do that. The only time

people believe you have to do that is when so

many other people do it that they think this

is the normal way to do things.

Inside Steve Vai's Harmony Hut home studio. Photo by Lindsey Best

“Creamsicle Sunset” starts off with the

simple opening triad and inversions, and

then morphs into some delicious dissonances

that most rock guitarists probably

couldn’t gracefully maneuver.

Yeah, a song like that was like a little gift for

me, because it was so simple. I picked up the

guitar and I was just playing these triads—like an exercise you do when you’re learning

chords—but this particular time I played it,

it transcended the exercise and it sounded

like music. The whole song unfolded to me

and all I needed was that first bar—the triad

thing. When I came up with that idea, I had

my iPhone and I turned it on and played

those first three chords and left myself a

voice note, “Create a track that has these

inversions that keep building and building,

and going higher and higher, and has the

really juicy, beautiful chords in between.”

The whole thing was done before I finished

playing the third triad. My goal was that

every note in the song had to have its own

zip code, and it had to sound like a little

church bell that it owns. When you imagine

these things, that’s how you get them

to come into reality.

Parts of “John the Revelator” are reminiscent

of the scene in Crossroads that’s

right before the grand-finale guitar

duel—and then it morphs into “The

Book of the Seven Seals.” Were the two

songs conceived independently?

I came across this version of “John the

Revelator” online. The vocal arrangement

was done by two guys, Paul Caldwell

and Shawn Ivory, and sung by a high

school choir called The Counterpoint

Singers. I contacted the woman that ran

the choir and she sent me a cassette of

the only stereo recording they had. I put

it into Pro Tools, cut it up, and built the

song around it, but it still wasn’t good

enough. The piano was dull, so I hired

10 of L.A.’s finest and they came in and

sight-read this very intricate arrangement.

Then I triple-tracked them, so it’s

like a hundred voices.

But as far as “John the Revelator” and “The Book of the Seven Seals,” they were one song. It was a vision. To go from “John the Revelator,” which is heavy guitars and tuned-down octave dividers with these gospel singers—that to me is always the way gospel should be presented, heavy, hardcore guitars playing very musical things—to the second part, with this extremely white-sounding, Republican, Midwestern vocal arrangement. That’s such a contrast.

How did Beverly McClellan get

involved on that track?

I needed somebody to sing “John the

Revelator” and I thought I could do it,

but it wasn’t in my range. When I hosted

an event for NARAS [National Academy

of the Recording Arts and Sciences] with

Sharon Osbourne, I went into the audience

to check out what it sounded like

and this woman, Beverly McClellan, took

the stage and just tore it up. The moment

I heard her sing, I was just stunned dead

in my tracks. I thought, “She’s gotta

sing ‘John the Revelator’ for me.” I was

also thinking, “I don’t know. She doesn’t

know me and she probably thinks I’m

this crazy shredder guitar player,” which

a lot of these people who don’t know

anything about me just think. When I

got backstage, she was there waiting in my

dressing room with her CD and she said,

“I’m a big fan. I know your music and I’d

love to give you this CD.” I said, “Look,

we’ve got to do something.”

“No More Amsterdam” features Aimee

Mann, who also cowrote the song. I

understand she was at Berklee College of

Music when you were there.

Yeah, I was going to Berklee and Aimee

lived in the same building as me, four doors

down. We knew each other from saying

“Hi.” My girlfriend at the time, who’s now

my wife, Pia, was very good friends with

her—they were actually in a little band

called the Young Snakes. I had this weird

preconceived idea—because I was very insecure

at that time—that she thought I was

a crazy, long-haired shredder and that I was

doing all this progressive stuff. When you’re

critical and you’re insecure, you think that

anybody who’s not doing the thing you’re

doing doesn’t have any appreciation for

what you’re doing, and the people who are

doing it always think they’re doing something

better than you.

Many musicians feel that way.

Most people feel that way. Aimee wasn’t

like that at all, but I didn’t know that. So

when I was doing “No More Amsterdam,”

I started to write the lyrics and I just

had a really hard time. Pia said, “Well,

why don’t you call Aimee?” I thought,

“Aimee doesn’t want to have anything to

do with me.” But I couldn’t have been

more wrong. She’s way above all that stuff.

It was my own insecurities that kept me

from going to her.

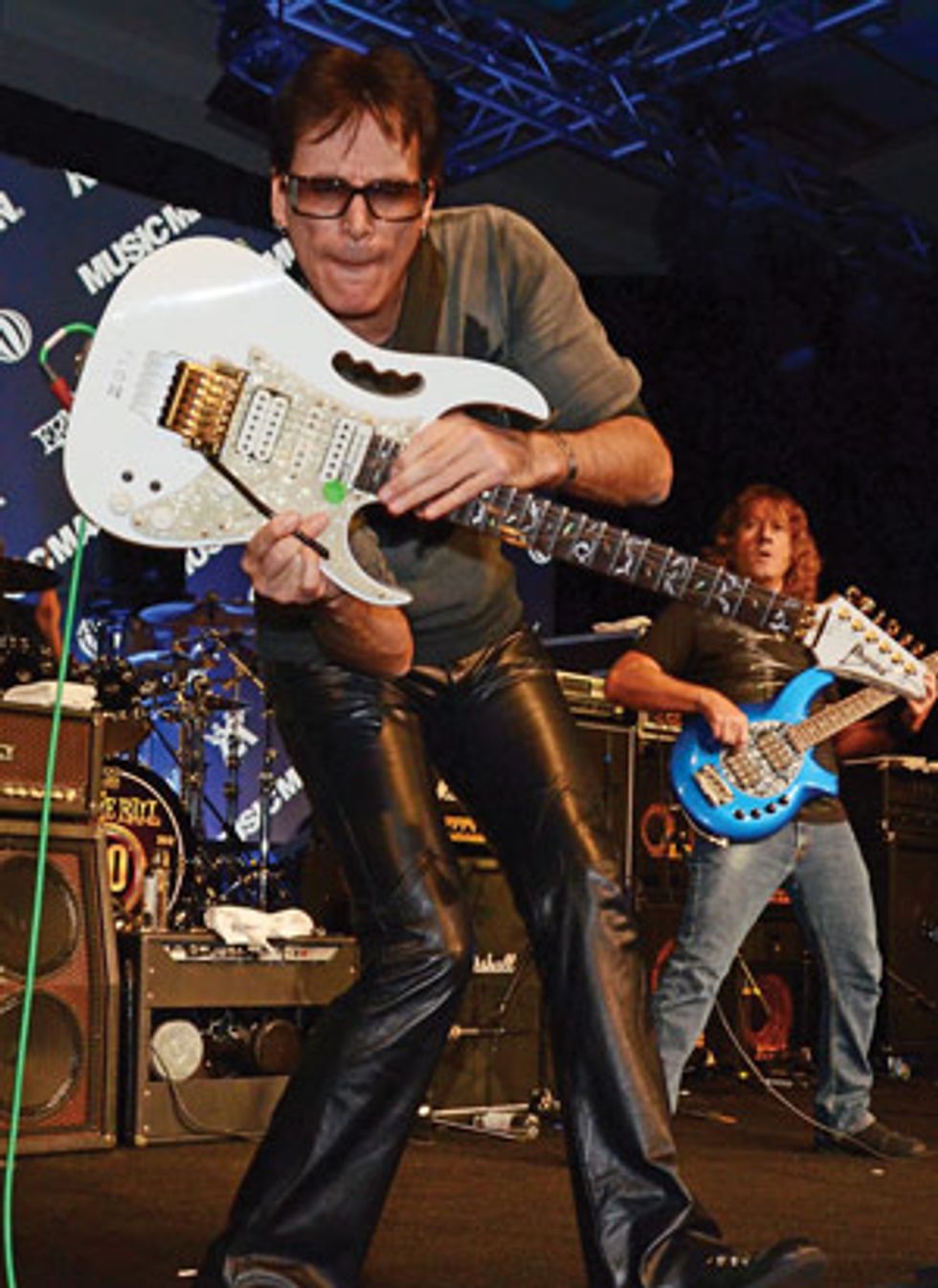

Steve Vai performs with a band that includes Dixie Dregs bassist Dave LaRue at the Ernie Ball 50thanniversary party at Winter NAMM 2012 in Anaheim, California. Photo by Marty Temme

You seem to always have a real clear picture

of what you want. Was it hard for

you to make compromises with Aimee?

For the most part, I’m very controlling—controlling in the sense that something

has to feel and sound a certain way to

me. Reaching out to somebody that’s able

to deliver that is part of the controlling

nature. Her contribution fit perfectly

with my control-freak nature, because my

control-freak nature said, “Give it to her to

do whatever she wants with it, because it’s

going to be great.” We talked about it and

she just fit these lyrics in that were just so

much better than anything I think I ever

could have come up with. She also made

some vital suggestions about the form of

the song.

Let’s talk gear. What’s your main rig

right now?

Well I have a new head, the Carvin Legacy

3 VL300.

Is its smaller size designed to compete

with the lunch box-type amps that are

everywhere nowadays?

It’s designed to be a lot more convenient—smaller but still packing the 100-watt wallop. It’s a very simple, 3-channel

amplifier. You open up a Legacy, and

you’re going to see some very powerful,

simple wiring. In the process of designing

these amps, I’ve always been a real stickler

for the signal path and the motherboard,

and how many components are going into

it. Because every time you add a channel

or a loop or a master volume, it compromises

the main signal.

Do you use your Axe-Fx II just for effects?

Yes, just for effects. It’s the most transparent

piece of gear I’ve ever heard. With most

other pieces of outboard gear for the guitar

that I’ve played, there’s always a price to

pay—like latency, a roll-off at a particular

frequency, or a noise that happens. Or

there’s just programming that’s completely

and utterly ridiculous and nonsensical and

designed by nerds who want to fascinate

themselves with their intellect and couldn’t

give a shit about the mind of a musician.

There are people who do that because

they can’t play and they’re fascinated with

the electronics and make shit impossible

to figure out. I’m really simple, you’d be

surprised. My music might lead you to

believe otherwise, but I like things to make

sense. The Axe-Fx is the best-sounding

pass-through processor I’ve ever heard.

Tell us about the new pickups you

designed with DiMarzio—what tonal

characteristics were you going for?

They’re called Gravity Storms, and we’ve

been working on them for about a year.

If I were to explain, I’d say they sound

more analog to me than digital. All pickups

are analog, obviously, but you know

how when you hear something that’s

analog? The Evolution pickups [stock

units in Vai’s Ibanez signature models]

are very high output and have a very fat

bottom end and a very bright top end.

What I wanted with the Gravity Storms

was maybe a little less output—because

then I could crank other things. I don’t

know if they actually ended up with less

output, though, because we went through

so many pickups until I heard something

that felt really right.

Is it true you recently changed

string types?

I use Ernie Ball, but they just sent me

these new Cobalt strings. At first I didn’t

like them. There was something very

stretchy and slinky about them that felt

uncomfortable. I was so surprised that

somebody could make strings that felt

so different and responded so differently

than what anyone else was making. If

you took any brand of strings and put

them on my guitar, I’d be hard pressed to

tell you whose they are—because a lot of

these strings companies get them all from

one source. But Ernie Ball really processes

strings to make different sounds and different

feels.

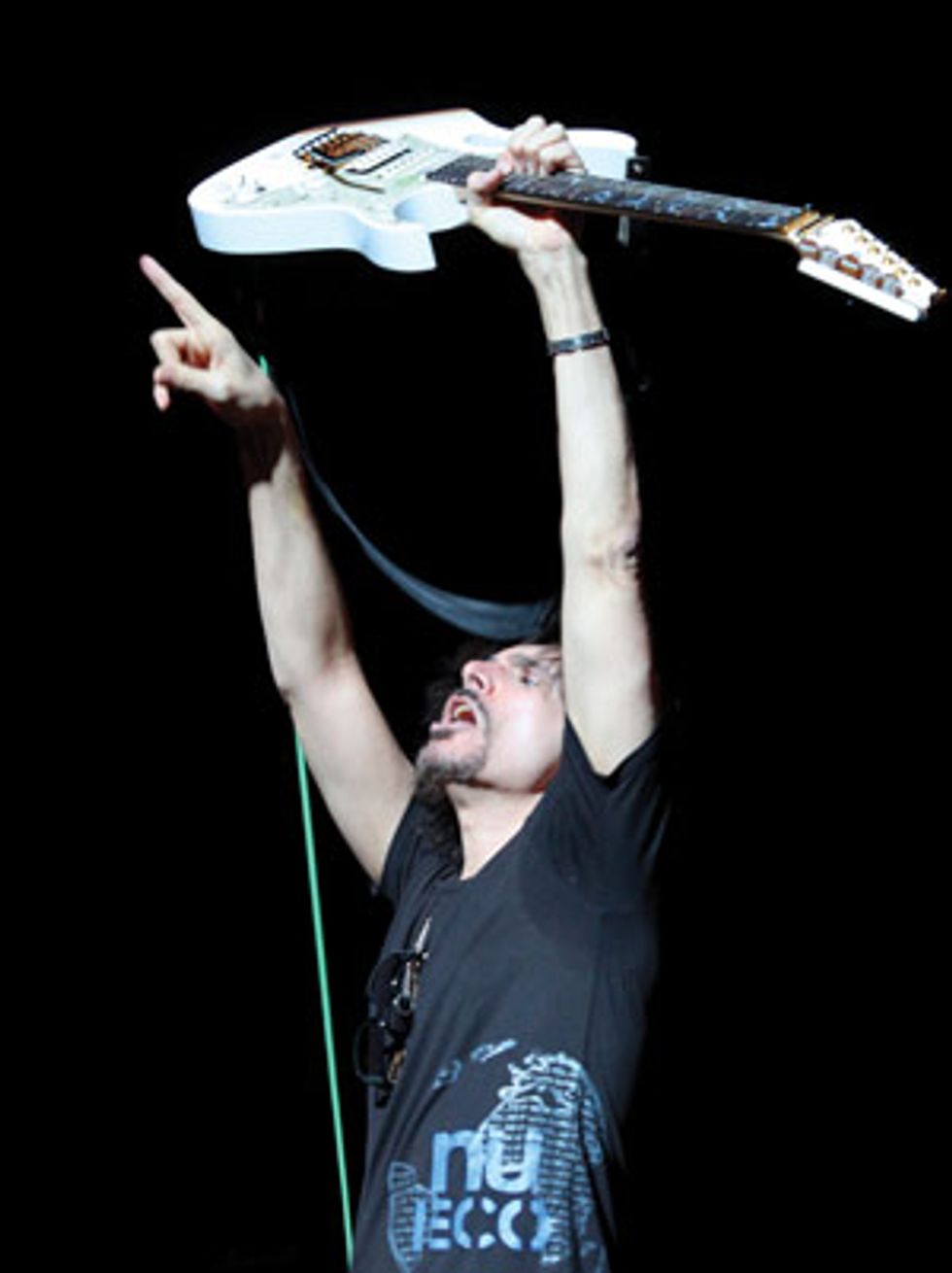

Vai gets a natural monkey grip during the 2010 Experience Hendrix tour at the Star Plaza in Merriville, Indiana. Photo by Barry Brecheisen

When I got these Cobalts, I was set off a bit because of the slinky-ness, like I said. I told Thomas [Nordegg, Vai’s guitar tech] to take them off the guitar, but he left them on. I had them on five guitars here at the house, and I just started using them—I don’t like taking time to change strings—and I started to get it. I was like, “Wow, they’re so much more controllable.” And the way the notes ring together when you clang them is very different, so I really grew into them and I like them a lot now.

You often pit guitar against timbres rock

guitarists don’t usually encounter—like

the orchestras or the gospel choir in

“Book of the Seven Seals.” Do you

accommodate your guitar sounds to fit

those situations?

Not usually. It’s according to how you

play and how you process your sound.

When I’m doing stuff with an orchestra,

a smoothly distorted melody guitar can

blend in very nicely with a violin or some

other instruments. As an orchestrator, you

have to know, “How does tuba compare

to a xylophone?” They’re very different

instruments—they’re organic instruments,

because you’ve got to blow into one of

them and you’ve got to hit the other one.

There are no electronics involved. That’s

the difference, and that’s the tone quality

difference in the guitar that makes it stand

separate from all the other orchestra instruments.

It is difficult to blend—very difficult.

You have to know how to orchestrate

it to speak a particular way. But this is all

subjective to the composer’s ear. This is my

vision for it.

Have you heard the new Van Halen album?

Yeah, I was really surprised. I thought the

sound was very visceral—very distorted and

very high energy. I was relieved, because I

was afraid Edward was losing his ability to

really play because I had heard rumors that

he had stopped playing for a long time. But

I was really surprised. It sounded like he had

that fire. It wasn’t the shell of greatness—I

was hearing greatness again. What was cool

was the way Edward and Alex can still lock.

They really locked in on hyper-speed stuff,

these grooves. I think I could take like three

or four songs at a time—it’s just so kinetic.

I was really surprised at Dave Roth, too. I

know how hard he works, but he kept working

harder and now his vocal range is much

greater than when I was working with him.

Really?

Yeah, I’m not placating. It’s very obvious,

and when I was hearing these notes I was

like, “Whoa.” I know Dave and I know that

he worked really hard. People don’t see that

because they don’t know him.

In your music, you’ve espoused experimentation

and taking guitar to the outer

limits—and, against the odds, you’ve been

very successful. Since you’re involved in

the business side of your Favored Nations

label, do you view submissions differently

now than you would have as just an artist?

If something stimulates you on an intellectual

or musical level but you think it

will have limited appeal, even within this

niche market, will you release it?

Well, I have—but it’s not that easy. For years

with Favored Nations, I plummeted money

into artists that lost a lot of money. Usually,

if you get it in a store, if it doesn’t sell, they

send it back. You can ship a half a million

records and get 499,000 back. So there are

a lot of things that go into deciding whether

to release a record: Is the artist capable of

continuing a career? Are they gifted?

Steve Vai's Gear

Guitars

Ibanez signature electrics

(JEM7V, JEM77, JEM70V, and

UV777), Ibanez signature acoustics

(EP5BP, EP10BP)

Amps

Carvin Legacy 3 VL300 heads,

Carvin Legacy 4x12 cabs with

Celestion Vintage 30s

Effects

Fractal Audio Axe-Fx II, Ibanez

Jemini, Morley Bad Horsie wah,

Morley Little Alligator volume

pedal, DigiTech Whammy

Strings, Picks, and Accessories

Ernie Ball Cobalt .009–.042 sets,

Ibanez heavy picks, Fractal

Audio MFC-101 MIDI foot

controller, DiMarzio cables and

ClipLock straps

When I listen to submissions, I listen for people who I feel have a vision of their own. When I come across things like that, I think, “What can I do for these folks?” Because a lot of musicians just don’t have an understanding of the business—but I do. I’ve thought, “I can’t put this out, because it’s just not going to sell at all, so what can I do?” So I started Digital Nations, and it’s only digital releases. We have digital distribution in several hundred stores around the world. For, like, a hundred dollars you can sign up and get your music distributed around the world. In that regard, we’re more of a service than a label—I have to make it make economic sense.

Long ago, you said if you were a mailman,

you’d be just as content. Do you

still feel that way?

I feel even more so, because you take who

you are wherever you go. It doesn’t matter

if what you’re doing is wildly successful or

not. What matters is if you find satisfaction

in it. I know that sounds cliché, but

it’s the truth. And I’ve seen it. You know

I’ve been there and back and there and

back again. The bottom line is you can be

playing to 30,000 people and have a hit

single and multi-platinum record, but if you

don’t like the music you’re playing and if

the guys in the band are assholes but you’re

tolerating them because of what’s at stake,

you’re gonna be unhappy and that whole

period of your life is going to have a dark

shadow over it—and that’s going to be your

memory. What’s that worth? It’s not worth

anything. If you can let go of that and find

the thing that excites you the most and cultivate

that, you’re always going to be happy.

And usually that’s the thing you’re going to

be most successful at.

YouTube It

For a taste of Steve Vai’s quirky brand of virtuosity, check out the following clips on YouTube:

Vai performs “The Attitude Song”—one of

his seminal classics—with the Metropole

Orchestra in 2008.

Three necks are better than one, as Vai demonstrates

during this 2003 G3 concert (with

Yngwie Malmsteen and Joe Satriani) in Denver.

From 4:34–4:40, Vai plays the most insane

5ths-based sequence ever.

Vai and bass god Billy Sheehan perform “Shy

Boy,” the unison-filled shredfest that symbolized

their respective instrumental powers during

their stint with David Lee Roth in the mid

’80s. Here, Sheehan takes vocal duties.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.