|

With the election of 2008 rapidly drawing to a close amidst a financial crisis and national uncertainty about our next move as a culture, it seems that populism has become all the rage, the en vogue form of political rhetoric. Our presidential candidates criss-cross the country, pacing in town halls and standing on picnic tables, proclaiming Power to the People! We’re told we now have the power to change things, that we are in charge. The elites are out; the average Joe is in. Wall Street is railed against, Miller High Life is cheaper than ever and Larry the Cable Guy seems poised for a curtain call. It’s a strange, strange world we live in.

|

For guitarists, the hilariously ironic thing about this sudden outcropping of populist sentiment is the fact that we’ve been taking power into our own hands for decades. That’s not to say that guitarists are all of a certain political disposition, but instead that we uniformly believe in a certain way of looking at the musical world. You have the power to construct the tone you want; it literally begins in your hands and your fingers. Still don’t like your sound after mastering those hammer-ons and double stops? Get your hands on a new guitar, a new amp, a new stompbox. Don’t like the options available to you? Create your own gear; start your own boutique line. The only thing limiting your tonal exploration is your gumption and drive.

It’s all part of a philosophy rooted in the ideas of self-reliance and empowerment, and ultimately a belief against any one, controlling interest when it comes to your sound, whether that be a corporation or a guitar tech. If guitarists were to establish a platform, the opening sentence might read, “People have a right to good tone, unobstructed by ploys, gimmicks or interference.”

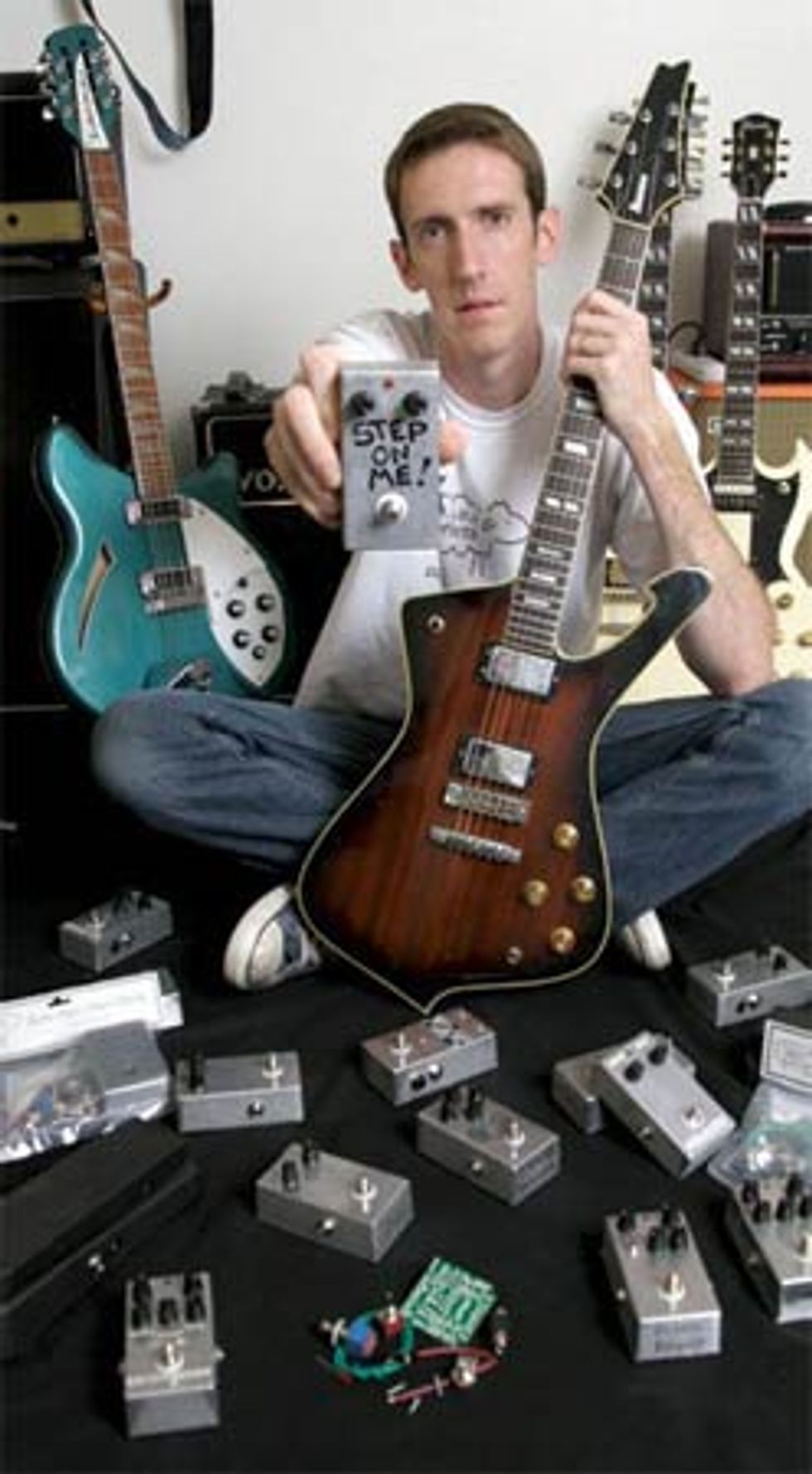

It’s all part of a philosophy rooted in the ideas of self-reliance and empowerment, and ultimately a belief against any one, controlling interest when it comes to your sound, whether that be a corporation or a guitar tech. If guitarists were to establish a platform, the opening sentence might read, “People have a right to good tone, unobstructed by ploys, gimmicks or interference.” All of which brings us to one of the industry’s most recent monuments to tonal self-determinism, a small three-person operation known to savvy players as Build Your Own Clone—frequently referred to in its shorthand form, BYOC. Located in the small town of Moses Lake, Washington and operated out of a two bedroom house full of amps and guitars, BYOC has been supplying guitarists all over the world with the ingredients necessary to build their own pedals, supplied in the form of anyone-can-do-it kits. As the name would imply, the designs are all primarily “clones” of classic circuits, those sounds that have long been sought after by guitarists but have escaped their reach due to the acceleration of the vintage market in the past few decades.

| The circuits are only half the story. Click here for a gallery of impressive BYOC pedals, built and decorated by BYOC forum members. |

And despite the fact that mega-corporations like Microsoft and Boeing dominate the area—Moses Lake is situated directly between two of the state’s largest cities, well within the hub of tech and aerospace innovation known as the I-90 corridor—BYOC has maintained a comparatively simple existence. The company exists with the company existing primarily in the form of a pared down website and its accompanying forum, providing everything from a place to post kit development requests to soliciting technical advice from other BYOC devotees. Spending a few minutes on the BYOC website leaves you with the impression that this is one of the most grassroots, people-centric projects to emerge from the guitar industry in years. And while he denies any political/social angle to his business, owner Keith Vonderhulls—an even-keel guy who generally avoids self-promotion or hyperbole— does takes a certain amount of pride in his product’s relative non-complexity. “I think people are learning that doing it yourself isn’t as hard as they thought it was,” he says from his bedroom-turned-office. “It’s like baking cookies—as long as you use the right ingredients and follow the recipe, it’s going to turn out good every time.”

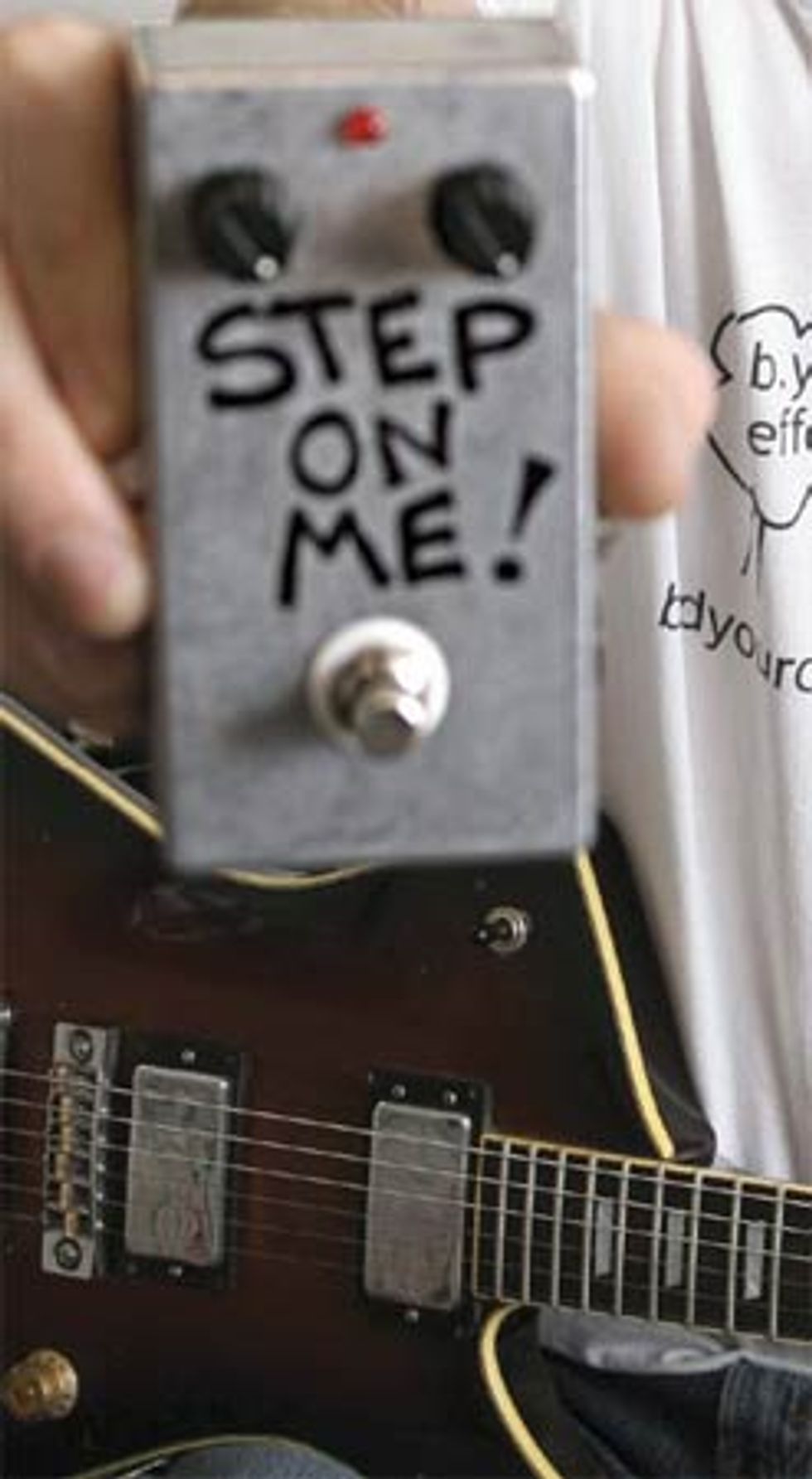

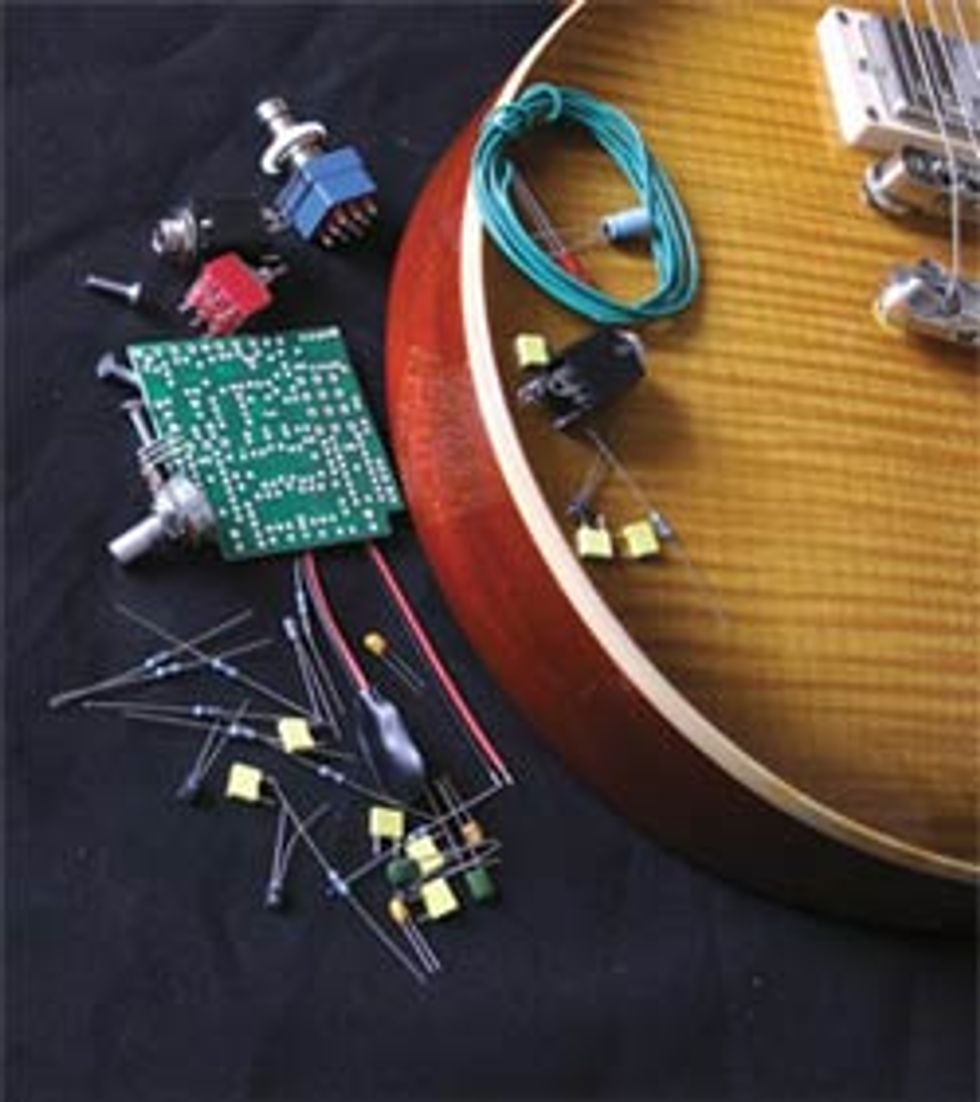

While that may seem like a bold statement to anyone who doesn’t have an electrical engineering degree, Vonderhulls has managed to make that recipe incredibly easy for anyone with equal doses of patience and courage. BYOC kits arrive meticulously organized, with predrilled and labeled PCBs, blank canvas enclosures and the components partitioned into tiny, plastic bags. While the instructions do come in the form of a PDF file—meaning a computer has to become involved in the process, if only briefly—they are generally full of large images, line drawings and straightforward instructions. It’s a recipe that has been refined since the first kits hit the street, one that has simultaneously become more focused on the steps that matter and stripped of the details that don’t. “When I first started, I really dumbed it down,” Vonderhulls says. “I included actual photos of every solder joint. I actually got complaints about it from people, saying it slowed the build down. They told me I should edit my instructions.”

While that may seem like a bold statement to anyone who doesn’t have an electrical engineering degree, Vonderhulls has managed to make that recipe incredibly easy for anyone with equal doses of patience and courage. BYOC kits arrive meticulously organized, with predrilled and labeled PCBs, blank canvas enclosures and the components partitioned into tiny, plastic bags. While the instructions do come in the form of a PDF file—meaning a computer has to become involved in the process, if only briefly—they are generally full of large images, line drawings and straightforward instructions. It’s a recipe that has been refined since the first kits hit the street, one that has simultaneously become more focused on the steps that matter and stripped of the details that don’t. “When I first started, I really dumbed it down,” Vonderhulls says. “I included actual photos of every solder joint. I actually got complaints about it from people, saying it slowed the build down. They told me I should edit my instructions.” Part of the effort to ease newcomers into the world of circuit building has been the inclusion of the company’s Confidence Boost—literally a simple linear boost and buffer—and a signal tester kit in all first-time orders. “If you can do paint by numbers, you can build your own pedal,” says Matt Keon, a longtime customer who is now involved in BYOC’s creative and marketing efforts. “But [Vonderhulls] has introduced some products that make things even easier, like giving first-time buyers the Confidence Boost kit for free. It’s like saying, ‘Here, try this first. It’s unknown territory and it might be a little scary, but give this a shot before you take the other pedals out of their packaging.’” It’s a strategy that has largely been successful for the company, as most first-time purchasers end up becoming prolific repeat customers. “It’s very addictive after you build your first pedal,” says Vonderhulls. “It’s such an empowering thing. Once [a customer] builds their first one and all their friends geek over it, they come back and buy three or four more. Some guys buy one and then come back and buy everything.”

It’s difficult to find anyone that has a bad thing to say about BYOC; everyone you talk with has the same infectious enthusiasm for the concept. “I’ve built every kit except for one,” says Keon. “I basically built my entire pedalboard up from dust.”

Perhaps not surprisingly, BYOC grew out of Vonderhulls’ earlier flirtations with establishing his own boutique line. A self-professed “pedal geek” from his earliest years of playing, he began learning how to build pedals around 2001 after seeing a Z.Vex pedal on eBay. “I thought, ‘This is a handmade item someone made in their garage or something’ and that I could do that. And when I saw that someone was getting $300 for the pedal, I decided that’s what I wanted to do,” Vonderhulls says. He eventually began turning out clones of Fuzz Faces, Tube Screamers and Tone Benders under the name Big Tone Music Brewery in his spare time; it was with these early designs that Vonderhulls had the experiences that would form the basis for BYOC. “People kept sending pedals like the Fuzz Face back and saying things like, ‘You know, it sounds great, but could you cut the bass out of it a little bit?’ And I’d say sure, but I was only changing one capacitor value, and it would almost be easier for them to do it themselves,” Vonderhulls recalls. “So I thought, I should put together a Fuzz Face kit and actually let people build it for themselves.

“I started off with ten kits and put an ad on Harmony Central. They were gone in a week, and everyone was raving about them. I figured, ‘I must be on to something here.’”

“I started off with ten kits and put an ad on Harmony Central. They were gone in a week, and everyone was raving about them. I figured, ‘I must be on to something here.’” From there the company was off and running, with Vonderhulls formally licensing the business in 2005. Without any viable competition in the kit business, the company’s growth was stratospheric at first, marketing a handful of distortions, overdrives and modulation effects to clamoring guitarists. As the customer base and the product line evolved, Vonderhulls was eventually able to bring aboard two employees, including Dave Lobie, a lifelong guitarist and veteran of the Seattle underground scene, to handle production of the kits and stand-in as the shop’s resident shredder. “I’m the guy that makes sure everything is put together in the kits, and I’m also the guy that gets in trouble when they’re not in the kits,” Lobie says jovially.

A large part of BYOC’s success can be attributed to the very forums that gave rise to his business. A section of his website is full of suggestions from users for future builds, from tweaks and minor modifications to full-on development requests—a valuable cache of feedback that Vonderhulls eagerly samples from. Customer service is handled by a handful of moderators on the BYOC board and builders experiencing problems can get advice from more experienced hands, allowing Vonderhulls to focus on more pressing business concerns. It’s a self-contained community that essentially cares for itself, and a reality that Vonderhulls is more than happy to harness. “Our forum just hit 3000 users and it has only been up for two years. Of course, it depends on what viewpoint you’re looking at it from, but for something as esoteric as this, that seems pretty good.” Of course, even with a near-rabid fan base, BYOC has encountered its share of trials and tribulations. As the orders have stacked up and Vonderhulls’ small team has hustled to keep the pipeline flowing, mistakes unique to the BYOC business model have occasionally crept in. Complaints about kits shipping with missing parts creep up on the “Praise, Complaints and Suggestions” section of the forums (“We’re only human and a lot of these kits have quite a few parts, but most of the time we’re dead on,” says Lobie); defective components from suppliers have forced recalls of kits and frustrated customers; much needed components can take months to arrive (during my conversation with Vonderhulls in mid-September a component ordered in July finally arrived at the shop, to much excitement); hand-drilled PCBs have the potential to return from production with errant holes, extending the wait for a particular kit and complicating fulfillment. It can be a demanding business at times, and Vonderhulls is the first to admit it. “I’m feeling a little stretched thin right now; I just keep telling myself that it’s going to be worth it pretty soon. Sometimes I wake up and I think, ‘I wouldn’t wish this on my worst enemy,’ and some days I wake up and think, ‘I’m one of the luckiest people on the planet.’”

Fortunately, Vonderhulls has a competitive streak in him—he spent his years before diving into the effects world as a dedicated road cyclist—that has kept his company in the thick of it, despite the occasional crisis. He has upgraded his equipment, adding a CNC machine to the operations; he has begun a rigorous process of beta testing all of his builds and components to make sure that they’ll stand up to the stresses of use; he’s tightened up the quality control processes, adding more checks and balances; and he has made an effort to learn more about the business side of the industry to keep things moving smoothly. “Just this year, I learned about purchase order agreements, which will be a huge thing for me in terms of getting costs down, but it will be even bigger in terms of knowing the parts will be there when I need them,” he says.

Fortunately, Vonderhulls has a competitive streak in him—he spent his years before diving into the effects world as a dedicated road cyclist—that has kept his company in the thick of it, despite the occasional crisis. He has upgraded his equipment, adding a CNC machine to the operations; he has begun a rigorous process of beta testing all of his builds and components to make sure that they’ll stand up to the stresses of use; he’s tightened up the quality control processes, adding more checks and balances; and he has made an effort to learn more about the business side of the industry to keep things moving smoothly. “Just this year, I learned about purchase order agreements, which will be a huge thing for me in terms of getting costs down, but it will be even bigger in terms of knowing the parts will be there when I need them,” he says. Improvements aside, Vonderhulls says the most problems with his kits arise out a lack of patience on the part of the builders. “Some people get fatigued [while soldering], and that’s when they start making mistakes. The only people that ever have problems are the people who rush through the builds. For example, I’ll get a call on Thursday from someone asking me to overnight them a pedal so they can build it on Friday for their gig on Saturday. And sure enough, Friday night they’re calling me and emailing me with all capital letters and exclamation points, saying, ‘It doesn’t work! You need to fix this or tell me what I’m doing wrong here!’” he relates, with only the slightest hint of exasperation in his voice, before writing it off as simply a part of the business.

And despite the company’s evolution, some things remain unchanged. Vonderhulls continues to develop his kits in the same way, by gauging the general level of interest on his own forum and then buying a handful of the original pedals through dealers or eBay—a task that can take a considerable amount of effort, energy and capital for the most vintage of models. He then tries to track down schematics for the pedal, sometimes getting them from the manufacturers, and sometimes culling them from trusted online sources—“usually you run into a lot of contradictory schematics online, but there are circuits that have been pretty well explored by the DIY community,” Vonderhulls says. It’s a process that can take months and one that can rely heavily on the availability of needed components— something that, much like soldering, can require mammoth amounts of patience.

And despite the company’s evolution, some things remain unchanged. Vonderhulls continues to develop his kits in the same way, by gauging the general level of interest on his own forum and then buying a handful of the original pedals through dealers or eBay—a task that can take a considerable amount of effort, energy and capital for the most vintage of models. He then tries to track down schematics for the pedal, sometimes getting them from the manufacturers, and sometimes culling them from trusted online sources—“usually you run into a lot of contradictory schematics online, but there are circuits that have been pretty well explored by the DIY community,” Vonderhulls says. It’s a process that can take months and one that can rely heavily on the availability of needed components— something that, much like soldering, can require mammoth amounts of patience. Overdrives continue to be BYOC’s most popular products and competition remains rather slim; General Guitar Gadgets is the only other online outlet that Vonderhulls is aware of providing ready-to-build kits to customers (“I’m really surprised no one else is doing this,” he admits). People outside the guitar industry still hear the name Build Your Own Clone and imagine him working on some sort of twisted genetic experiments. No matter how complex the circuit, the instructions still have to remain simple and accessible—a true feat, Vonderhulls says, as the builds have gotten more and more complex.

And even though he’s made it clear that he won’t touch it, he still gets requests for pedals currently in production by other boutique builders. “I get at least one or two emails a day asking me to clone a Klon or stuff from Lovepedal, like the Eternity or the COT50,” Vonderhulls says with a sigh. Contrary to what critics might allege, BYOC is not trying to rip anyone off or passing original designs off as their own in some sort of electronic plagiarism. While the legality may seem questionable, it is not; classic circuits like the Fuzz Face and the TS-808 were never patented and thus remain free game for any number of builders to interpret, BYOC’s customers included. When pressed about the ethics of his endeavor, legality aside, Vonderhulls answers rationally, “Is it unethical? I don’t think so—a lot of these designs come from pedals that aren’t in production anymore. We’re not violating any trademarks and the demand is there.”

Which, in a looping, circular sort of way, brings the entire story back to its populist roots; BYOC is hard at work taking these highly rarefied designs, these long-sought sounds of another age, and giving them back to the people who deserve them, without screwing anyone in the process. Along the way he’s learned an extraordinary amount about the history and design of classic circuits, although Vonderhulls maintains that he isn’t to be considered an authority on any of it—in his mind, he is the average Joe next door with a soldering iron and broadband connection. He still looks up to builders like Zachary Vex and Robert Keeley and admires the new crop of shiny boutique pedals that emerge from the industry at regular intervals; the only difference is that now he enables guitarists to obtain great sounds without the price tag. He is dedicated to tonal fidelity, not circuit originality. He gives the people exactly what they want. In that way, BYOC could be described as the un-boutique, ultimately created for the people and built by the people. And what could be more populist than that?

Which, in a looping, circular sort of way, brings the entire story back to its populist roots; BYOC is hard at work taking these highly rarefied designs, these long-sought sounds of another age, and giving them back to the people who deserve them, without screwing anyone in the process. Along the way he’s learned an extraordinary amount about the history and design of classic circuits, although Vonderhulls maintains that he isn’t to be considered an authority on any of it—in his mind, he is the average Joe next door with a soldering iron and broadband connection. He still looks up to builders like Zachary Vex and Robert Keeley and admires the new crop of shiny boutique pedals that emerge from the industry at regular intervals; the only difference is that now he enables guitarists to obtain great sounds without the price tag. He is dedicated to tonal fidelity, not circuit originality. He gives the people exactly what they want. In that way, BYOC could be described as the un-boutique, ultimately created for the people and built by the people. And what could be more populist than that? The Kits

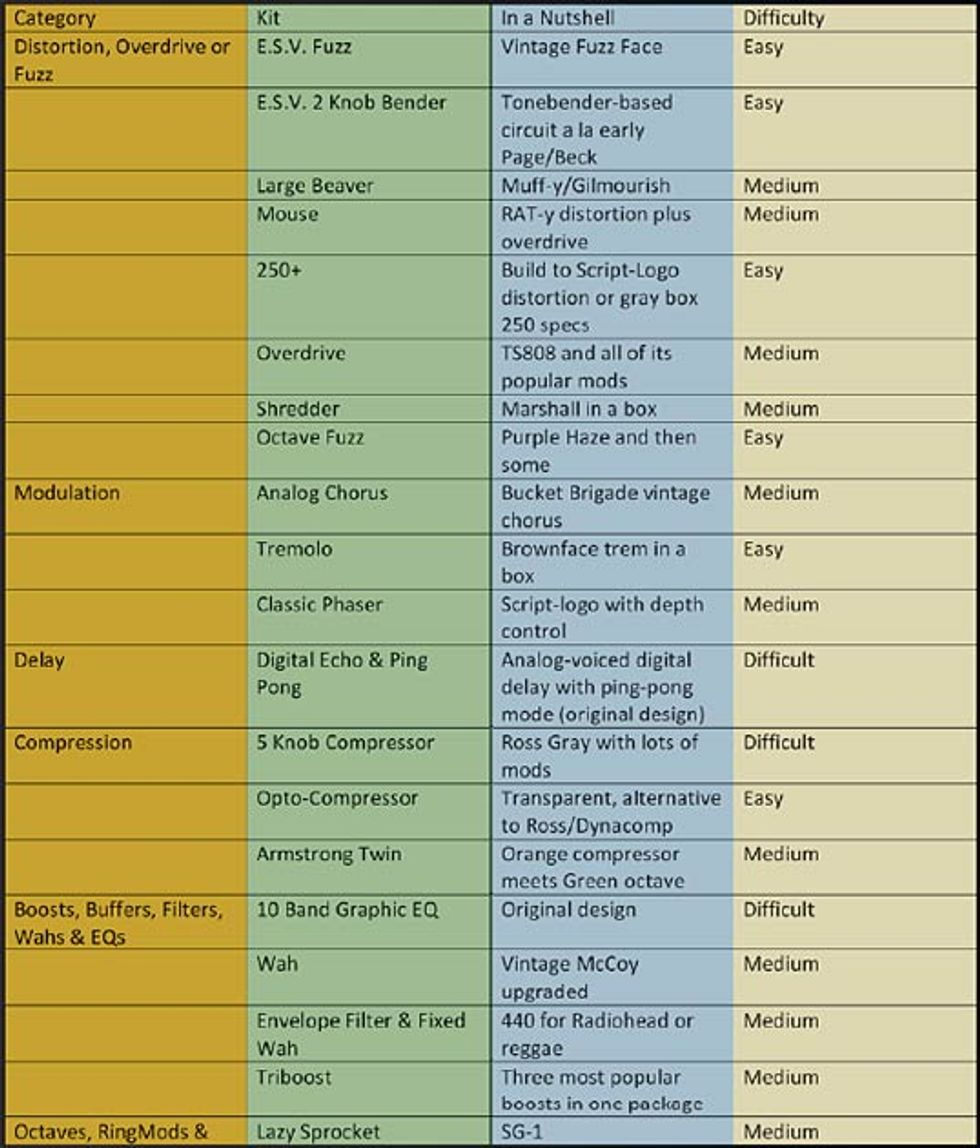

Here’s a rundown of BYOC kits currently available.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)