“I speak without reservation from what I know and who I am,” wrote 19-year old Ani DiFranco in the liner notes of her debut album, released in 1990. “I do so with the understanding that all people should have the right to offer their voice to the chorus, whether the result is harmony or dissonance. . . . Should any part of my music offend you, please do not close your ears to it. Just take what you can use and go on.”

Spending most of the ’90s on the road—often playing more than 200 shows per year—DiFranco went on to defy every music industry norm of the times. This was the pre-web era, when building a sustainable music career without the backing of a major label was almost impossible. But armed with her acoustic guitar and a die-hard work ethic, DiFranco slowly gained a devoted following of hundreds of thousands of fans, all while refusing a growing number of offers from record labels. Staying non-corporate and independent was a much bigger priority to her than fame and fortune, and as DiFranco boldly blazed her own path, she inspired legions of artists to follow in her do-it-yourself footsteps.

Today, DiFranco remains independent, outspoken, and prolific—not just as a songwriter, but as a guitarist. Using 50 different tunings, all discovered by ear, she fingerpicks, slaps, taps, pulls, plucks, and strums to accompany her silky voice, which is sometimes like a whisper in your ear, and at other times like an 18-wheeler hurtling past. Her lyrics, which are thick with metaphors and eclectic turns-of-phrase, run the gamut from deeply personal to overtly political.

Onstage, DiFranco is a force to be reckoned with. Exuding charisma, she is an animated, give-it-your-all performer. Cracking jokes between songs, flashing her joyful, wide-eyed grin, and talking to her audience as if they’re old friends, DiFranco remains a true folksinger in spirit, even though her music spans many genres, including pop, rock, jazz, funk, blues, hip hop, and spoken word.

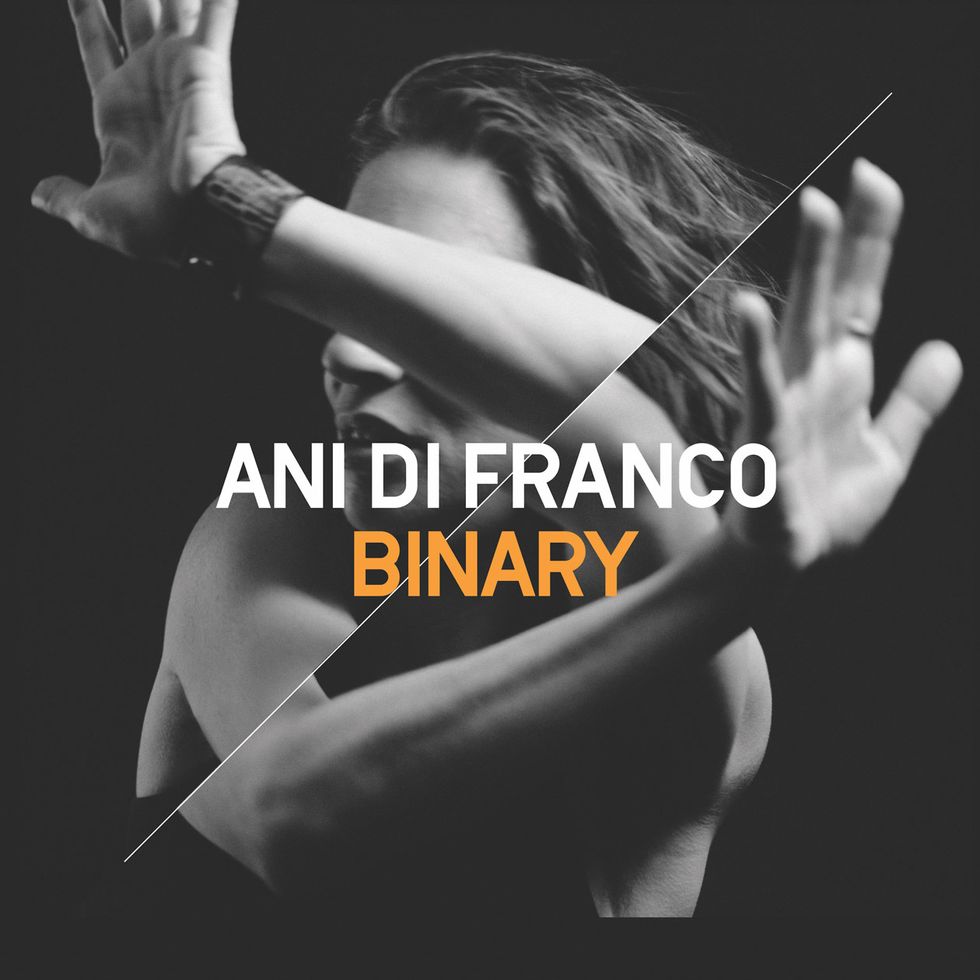

PG recently sat down with DiFranco on a sunny afternoon in New Orleans, where she lives with her husband, engineer/producer Mike Napolitano, and their two young children. With her favorite guitars and songwriting journal by her side, we talked about Binary—her 19th studio album on her own Righteous Babe Records—songwriting, and all things guitar.

What is special to you about Binary?

Well, first and foremost, the crew. Lucky for me, I’ve been in this game long enough and I’ve met some amazing people. My core band, Todd [Sickafoose, bass] and Terence [Higgins, drums], are just super uplifting musical souls. It’s very much an expression that we make together—we interpret the songs together. And Jenny Scheinman [violin] and Ivan Neville [organ, clavinet, bass, piano, Rhodes, and Wurlitzer] are both amazing musicians. I’ve had the pleasure of playing with them more over the last few years, and so I roped the two of them into the core of this record, too.

How much did you instruct what the other musicians contributed?

I think when I was younger I hadn’t yet learned that for someone you’re working with to try and be in the moment, while also trying to do that thing you told them you wanted to hear, is a conflict. So I’ve come to a place in my life where I just want to work with people who bring it, and I don’t want to say a thing. I have that kind of relationship with everyone on this record. Then, of course, Mike [Napolitano] recorded it and Tchad Blake mixed it—just all these people who could not be better at what they do. So it makes delegating excruciatingly easy.

I see that Justin Vernon of Bon Iver contributed vocals to your song “Zizzing.” How did that collaboration come about?

We know each other from working together on [singer-songwriter] Anaïs Mitchell’s folk opera called Hadestown. I wanted a chorale thing, meaning voices that were not just singing backup. I do that a lot with my bullet mic and I was just like, “Enough of me and my bullet mic!” So I called Justin. I love his sound.

Can you describe your bullet mic? Is that how you get your telephone-voice sound on your albums?

Yeah. It’s actually an old rotary phone handset my friend Scott put a 1/4" jack on instead of the phone cord. It’s super cool. It’s the sound of all of my records. It’s my backup singers. And there’s just something about the sound of an old telephone. But my near and dear, like Mike and Todd, they give me shit. They’re like, “Put down the phone, Ani!” [Laughs.] But I swear I’d record all my vocals through it if they would let me.

Did you use any new guitars or new gear on this record?

Well, not new per se. The guitar that I mainly record with these days is the guitar that my mentor, Michael Meldrum, gave me. [The late musician was DiFranco’s childhood guitar teacher and made one album for her label.] It was his last guitar. We call it the “GibsMart.” It’s a Gibson guitar with a Martin top, because it got stepped on. So it’s like a cyborg guitar, but it just—you play it, and it’s just like, yeah.

I’ve always played Alvarez guitars, and at some point, my husband, Mike, was like, why don’t you try an old guitar? So now I play some old Gibsons, even onstage. Because you can have a conversation on a level that you can’t necessarily have with a guitar that doesn’t have a soul yet. But this guitar, the GibsMart—everybody that comes through this studio records on it now. It records great. I’ve done shoot-outs with this guitar and every other fuckin’ one I own, and it’s like yep, that’s the one.

DiFranco’s 19th studio album was recorded by her producer and husband Mike Napolitano and mixed by Tchad Blake. Guests include R&B horn giant Maceo Parker, Bon Iver’s Justin Vernon, and Bowie bassist Gail Ann Dorsey.

Can you give us a few examples of alternate tunings that you used on this particular record?

Let’s see … [flips through songwriting journal]. “Zizzing” is in a tuning I revived from years ago. It’s E–B–B–G–B–D. It’s the tuning from “Not a Pretty Girl” and some other older songs I wanted to put back in the set. I always find if you have at least a handful of songs that are in that tuning, or in that tuning family, it makes it easier to keep them in the set lists. And that’s the same tuning for “Alrighty.” And “Even More” is in D–A–D–G–A–C. The C on the top—that’s been my new jam for a while now.

Tuning and re-tuning in front of an audience can add a whole extra level of stress. Do you feel that way?

Yeah. It’s a stupid idea. [Laughs.] Having a guitar tech is what enabled me in going way too far in the open tuning direction.

For someone who makes up her own tunings, and who is mostly self-taught, how do you remember all your tunings and hand positions?

I try to be organized and write down the tunings and the chord charts before I forget them. But I don’t always succeed. It always happens after the fact. But hopefully not too long!

Did you experiment with tunings early on in your playing?

Well, somebody showed me DADGAD, probably Michael. And I thought it was cool. And from there, I just started messin’ with it. And I think also what helped, or made it all seem plausible, was that I wasn’t really a schooled player. I took lessons from between the time I was 9 and 11. And then other things took over and I put down the guitar. And when I picked it back up, I had forgotten most of what I’d learned. So then I just started playing in my natural way, which is just making shapes and then remembering those shapes.

So you are an “untrained” musician, yet a very accomplished one. What would you say to a musician who believes that a player who doesn’t know scales or music theory isn’t legit?

I would say, “What are your favorite records? I betcha that most of the people on those records don’t know that stuff.” I mean, name all the great records of our coveted popular music history, and I betcha that most of those people are unschooled.

The title track of this record, “Binary,” combines a fun and funky groove with rather deep thoughts. How did that song come about?

Well, it’s just a poem, really. It started as a poem. And then I put a groove to it so that it wasn’t a show downer. [Laughs.] And it’s really just one little groove. I mean, sometimes, I feel like, fuck it, who needs a chorus, or a bridge, or whatever? Songs don’t always have to abide by structure. As far as the lyrics, the song starts with “in the blue glow of gizmos,” which is where most of us are residing these days—in isolation, interacting with machines. It’s like this rabbit hole of … lack of relationship. So for a while, I couldn’t stop thinking about the idea that consciousness is binary. The binary structure is actually underlying everything. From our atoms, to the positive and the negative, to the male and the female, to the dark and the light, to the life and the death—everything is a relationship of two things. And that kind of underlies this record in a lot of ways: the idea that everything is a dialogue, really.

Recently DiFranco began playing vintage guitars onstage—mostly Gibsons—“because you can have a conversation on a level that you can’t necessarily have with a guitar that doesn’t have a soul yet.” Photo by Richard Herron

Do you have a favorite song on “Binary?”

I’m pretty excited about “Play God,” because I feel like feminism is the answer—for all of us. I believe that patriarchy is the source of all our social diseases. I came to this awareness after enough years on the planet. You can’t create peace out of imbalance. Balance, in fact, is peace. So global patriarchy will never bring us to a peaceful world. It’s just impossible. And feminism is the way that we address patriarchy. So we have to empower the feminine to heal our world. And to empower women, you have to have reproductive freedom! That’s step one to emancipating women globally.

What were your initial goals when you first started playing guitar?

I feel like I was blessed early on, with having no goal. I didn’t want to pick up girls or be famous or whatever the usual motivations are. I was just kind of thrilled with the sounds. So I learned single-note pieces from these books before I learned chords. And by the time I learned chords, I was already hooked.

When you picked the guitar back up and started writing songs in different tunings, were you using a tuner?

No. I didn’t know the name of the notes. I think I have a solid pitch ear. But when I’m onstage, I have to use a tuner because my brain is too in flux. There’s too much going on.

What is your go-to guitar if you’re just hanging out and playing at home?

Well [grabs a guitar], I bought this Gibson a little while ago in my quest to find new old guitars. And the action on it is really high. I play with pretty high action because otherwise the strings buzz with the amount that I pull. I think it’s a 1960s LG kind of thing.

Ani DiFranco’s Gear

Guitars• 2 Alvarez-Yairi WY1 Bob Weir signature acoustics with Alvarez System 500 preamps

• Alvarez MSD1 short-scale dreadnought

• Alvarez custom baritone

• 1930s Gibson-made Cromwell tenor guitar with Fishman archtop pickup

• Vintage Epiphone Zenith tenor guitar

• 1960s blonde Gibson LG (“The Piss Gibson”)

• The “GibsMart” (studio)

Amps

• 1960s Magnatone Twilighter 260 2x12 combo

• Rivera Sedona 15" speaker combo (live)

• Fender Champ (studio)

Effects

• Klark Teknik DN360 rackmount analog graphic EQs for each guitar (live)

Strings

• D’Addario EJ16 (.012–.053) and EJ17 (.013–.056) • D’Addario EXP23 Coated Phosphor Bronze baritone (.016–.070)

If you had to take just one of your guitars on tour, which one would it be?

Oh, wow. I guess that my go-to would be the guitar I call the Piss Gibson [laughs], because the case got pissed on by one of my cats. It just really translates well. It’s blonde, and I believe it’s an LG, and it’s also an early ’60s kind of model.

Have you unintentionally become a Gibson girl?

Yeah. But Alvarez has been so gracious with me over the years. And even after I’ve incorporated some older and higher-end instruments into my arsenal—mostly Gibsons—I still keep the mini Alvarez [a 3/4-size MSD1 model] in my stage arsenal because it just has its own sound and all of the songs that I’ve written on it … it’s just gotta be that sound. And I also keep one of my Alvarez WY1s in my arsenal because I wrote a lot of songs on the WY1. A lot of my playing style was developed on the WY1, and some of those old rockers—there’s just something about the inherent compression of those guitars. It’s more all-forward. And sometimes when I’m rockin’ out, the buoyancy of the older instrument is not what I want in that moment.

You play a lot of tenor guitar onstage and in the studio. How were you drawn to tenor guitars?

Having a kick-ass bass player, mainly, and having an awesome drummer. There’s just something about that narrow, midrange space that the tenor takes up that works really well when you have a bass player and a drummer along for the ride.

A lot of us pick up the guitar and play the same chords or the same rhythm and we get bored. Do you have any tricks for when you’re experiencing this sort of thing?

Yeah. I do that too. But … open tunings! And another thing is just to have a baritone guitar and a tenor guitar. You don’t have to change the tuning. You just have to change the type of guitar you’re playing and it will bring something new out of you.

So even after 37 years of playing guitar can you still just turn your tuners and put yourself in a new place?

Yeah! That is the super refresher. I mean, check this out [grabs the guitar and starts tuning it by ear]. It’s a total sickness [laughs]. I’ve explored every plausible open tuning and then—this is my new open tuning: D#–A–D–G–B–D#. And it gets really hard to sing over because you have this complex chord and then it’s like, “What note sounds right?” Very few! Which to me, after almost 40 years, is a welcome challenge.

I’ve read that you get four different tracks out of each guitar take. Is this still your approach, and how do you do that all in one take?

Well, often these days I don’t end up using the DI at all. I just mute that channel and then it’s just the mic and the amps. But anyway, you go into the DI box and then you “Y” outta there. And one of those is going directly onto tape and the other one is “Y-ing” again to two different amplifiers. I use a Magnatone and a distortion-type amp. Onstage, that’s a Rivera, but in the studio, I use squirrelly little low-wattage vintage amps that distort easily without getting real loud, like a Champ. But there’s a lot of hum issues when you’re doing this. To just go direct and also go through an amp, you’re gonna get a hum. And it’s gonna take you an hour—if you’re lucky—to get rid of it. It’s always a problem, and often you have to ground-lift something and hope for the best. Hope you don’t blow yourself up. [Laughs.]

When you record, do you track vocals and guitar at the same time?

It depends. I’ve made so many records and it’s happened in all different ways. Lately, what the process has been is try to do live takes with the band. So we’d get the live take, but then I would do my parts over to get a better sound. And that’s actually been an interesting journey. Because the band is playing off of me, live. We’re performing. And then when I overdubbed, I was trying to get myself back to that moment. And when I stopped listening to the vocal that I was singing, and started really hearing the band, that’s when I knew that I was back in that moment. And I think that’s what it means to make music to begin with—not to listen to yourself. So when I could feel the band come alive, that’s when I knew that I was in the zone.

What are your preferred vocal mics?

For live shows, I use an Audix OM5. When I had a super loud band, it was just feedback after feedback, so one of my guys suggested the Audix because it has a really tight pattern. In the studio, we have a Neumann U 47. It’s the best mic in the house. There’s also a [Telefunken] ELA M … It doesn’t have the super high or the super low of the Neumann, but it’s got a real strong presence in the middle.

You developed tendonitis in your arm many years back due to your aggressive playing style and constant touring. Does this affect how you play guitar or what you play on guitar?

Well, these days I’m gigging a lot less, because of my kids. I don’t leave home for more than two weeks at a time. But if there’s anything that I could tell somebody about tendonitis, from my experience, it’s don’t hit the wall. Once you get to the place that I got to … I don’t think I’ll ever return to that pre-injury state. And these days, by the third tour in a few months, it’ll start getting hard.

What helps?

Super deep massage and acupuncture are the things that have helped me the most. And I used to ice my arms because I was told by a doctor to do that. But it made my arms stiff as fuck! And then there was an Eastern medicine practitioner who said, “What you need is more circulation—more heat!” So now I have heating pads that I use before, and sometimes after, a show. And it’s way better. Also, now when I can feel it starting to hurt, I try and keep my position changing, instead of staying stagnant in the same position and using the same muscles.

You built your following by way of constant touring. Do you have any advice for someone trying to make a living as a live performer?

Really, the key is total presence. I never, ever got onstage and, you know, put on a show or decided on a persona or decided “I’m going to play the role of.” I was just like, “This is what I’ve got.” The job is total honesty. And I think that is something that people know they can trust about me. So that’s the only thing that I would say to another performer as any kind of advice. Your job is to lift every veil that you have—the ones you know you have and then the ones you don’t know you have. Just drop them all and be naked. That’s when you connect.

You’ve been touring and performing for large audiences for over 25 years. Is it as fun as it looks? And what are a few of your favorite things about being on the road?

It is so as fun as it looks. It’s just the best job ever. It really is a privilege. And to get paid for it is just … ridiculous. There were a lot of years there where it did become a grind, and I wasn’t as closely in touch with the thrill of it, or the privilege of it. But now I’m back to “Holy shit! I’m lucky!” And I’m so happy that I get to bring that out again with me.

And I’ve lived this lifetime on the road … I could tear up just thinking about it. I’m intimate with all kinds of corners of the world, all over the place. It’s such a thrill to be on this endless journey. And traveling these days—I’m so struck anew by how kind people are. Everybody that I talk to out there—people of every make and model—their first instinct is the same as mine: to be kind. And it’s so reassuring to me, to be out there talking to people all the time and go this is America. This is who we really are. All of that other stuff is just shit that we’re being bamboozled into participating in.

YouTube It

This close-up solo performance from the January 2017 30A Songwriters Festival in Santa Rosa Beach, Florida, puts the spotlight on Ani DiFranco’s extraordinarily percussive right-hand technique as she plays “Binary,” the title track from her new album, on her Alvarez MSD1 short-scale dreadnought.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)