As a kid growing up in Texas, Charlie Sexton had an unlikely babysitter in none other than Stevie Ray Vaughan. A family friend to Sexton’s single mother, the story goes that SRV played Hendrix records for young Charlie and his brother, Will, to keep them occupied while their mom was at work. As Sexton got older and started frequenting the tiny clubs in Austin’s blues circuit, SRV trusted budding guitarist “Little Charlie” to fill in for him onstage.

This is but a minor footnote in the musical life of Sexton, who is well known as Bob Dylan’s lead guitarist. (Sexton first joined Dylan’s band in 1999, and still tours and plays on his studio albums.) Charlie grew up playing the blues with the Vaughan brothers and, by age 12, was slinging licks and learning the ropes with other Austin legends like W.C. Clark and Joe Ely. At the ripe age of 16, Charlie scored a solo record deal and a hit, in 1985, with “Beat’s So Lonely,” a song from his first album, Pictures for Pleasure. At the time, The New York Times described him as a teen heartthrob in the vein of David Bowie, another icon who Sexton ended up working with later.

Sexton was in his late teens when high-profile artists started calling on him to play guitar on their sessions. “The first year I started doing anything professionally, one session was with Sparks, and then it was Don Henley, and then it was Keith Richards and Ron Wood,” Sexton remembers. “Shortly after that it was David Bowie and Dylan, so that’s a pretty crazy combo. That’s like a year-and-a half of my life, 40 years ago or something [laughs].”

All the while, he was playing in his own bands: most notably the Arc Angels with Double Trouble’s rhythm session and Doyle Bramhall II. Because Sexton could play styles running the gamut from his blues beginnings to pop, country, rock or whatever in between, it was hard to place him in a specific niche. He refers to his sphere of influences as a “triangle thing.”

“There’s this confusion of what I do and who I am or whatever,” Sexton says. “It’s also based on my own listening habits, which I think are shared with a lot of people. I call it the Wednesday-Saturday-Sunday thing. I listen to some records on Wednesday, some on Saturday, and on Sunday it’s something completely different. That’s where that triangle thing comes from.”

Dynamic is an understatement for Sexton, who plays many instruments besides guitar, including piano, drums, bass, and orchestral strings. He’s in his element when providing the atmosphere and musical glue for a kaleidoscope of projects. In addition to working with Dylan and making his own solo recordings, he’s produced albums for Jimmie Vaughan, Lucinda Williams, Edie Brickell, and Ryan Bingham. He just wrapped a stint playing on the Bowie Celebration tour, and holds a lifetime position as musical director for Austin’s Music Awards.

In 2018, he starred as Townes Van Zandt in the Ethan Hawke film Blaze, a biopic about unsung Texas outlaw troubadour Blaze Foley, who is played in the movie by actor-musician Ben Dickey. Sexton’s portrayal of the real-life icon provides the vehicle for telling the story of Foley’s life, through a series of flashbacks. Van Zandt, who also came to a tragic end, was one of Foley’s closest friends. Sexton (who also oversaw the movie’s musical production) is mesmerizing onscreen. His performance captivates with haunting authenticity—it feels like Sexton is Van Zandt.

on the piano.”

Blaze is based on the memoir Living in the Woods in a Tree: Remembering Blaze Foley by Sybil Rosen, who was Foley’s muse and a firsthand witness to the songwriter’s life. The entire Blaze project had a synergy fueled by a love for music, and Hawke, Sexton, and Dickey’s onscreen partnership and real-life friendships continued after the film wrapped. Sexton and Hawke recently launched a record label with Louis Black, called SexHawkeBlack, and Sexton produced Dickey’s new record, A Glimmer on the Outskirts, which is the first release for the label.

In real life, Blaze Foley was known for being drunk and violent, but his tender side is revealed through the lens of his lover, Rosen. The film’s raw telling of the tortured artist’s struggle and demise ain’t pretty, but it’s a testament to the idea that no one is definable by one quality—a sentiment Sexton has embodied in his decades-long career.

In this interview, Sexton discusses how he started, the guitarists who greatly influenced his own playing (“meeting Jimmie Vaughan was like meeting Elvis”), working with Dylan, details of his favorite guitars, and how he learned to produce. Throughout the conversation, he reveals nuggets of wisdom about the bigger picture of music.

You’ve been playing guitar since you were a toddler. Can you recall an “aha” moment, where something clicked and you thought, “This is what I’m gonna do for the rest of my life.”

That happened really quick. When I was really little I would watch The Johnny Cash Show religiously with my grandparents. I remember being at a family reunion at 7 or 8 years old with all my aunts and granny at the VFW, and at the end of it, my uncles got up and played country or gospel tunes or whatever. What it did to them was really powerful.

TIDBIT: While playing the role of Townes Van Zandt in Blaze, Charlie Sexton also oversaw the musical production of the film. The soundtrack includes Blaze Foley’s most popular tunes like “Clay Pigeons,” performed by Ben Dickey, as well as one Van Zandt song, “Marie,” performed by Sexton.

Johnny Cash was an idol of yours. Who else?

That was pre-teen. I grew up with the records my mom was listening to: the Beatles, the Stones, Arlo Guthrie was in the house, random ’60s music-machine stuff, the birth of garage psychedelia. I started hanging out and getting close to the Vaughans when I was really young. Jimmie Vaughan was probably the real guitar hero I was obsessed with.

Me and my brother, we opened for the Clash, who we met through Joe Ely, who gave me my first break. That was my first real, real gig. I came up playing mostly blues. That was the vehicle to play. Once I heard the Sex Pistols, I was like, what the hell is this? And then I became obsessed with Gang of Four and Andy Gill. I was seeking and searching out other things that weren’t immediately in front of me.

Is it true that SRV babysat you?

Yeah. I rarely ever played with Stevie, because he’d see me walk in and he’d hand me his guitar and take a break. He was going to get a drink, and he liked me. He was super, super, super sweet. I met Stevie before I met Jimmie, and then I met Jimmie and that was kind of like meeting Elvis.

Who would you say taught you the most about guitar in that time period?

For me, the point by which it all comes out of, like, if you made a map with a pin-drop and it goes out from there, it starts with Jimmie Vaughan. There’s something about Jimmie, who could play half the speed of his brother, but the tonal thing that he achieves, even on that first record [1979’s The Fabulous Thunderbirds]. I always refer to it as his brother is a really fast car, and Jimmie’s like a really fine car, like a beautiful old Cadillac with all the right stuff and it’s just kinda cruising.

That’s where it all comes from, and then I go to back to where he was getting the blues: Jimmy Reed, Freddie King, Albert Collins, Albert King, B.B. King. But then it goes into Frippian land and Earl Slick/Bowie stuff. The main record I tried to teach myself to play guitar to was Magical Mystery Tour, which was a nightmare. It’s not like the first Beatles album, where you can play the chords. Nothing stays the same within one track. That was exhausting at 9 years old with a crappy acoustic guitar. Guitar in general is pretty frustrating. It’s a terrible instrument. It’s not supposed to play in tune and nothing is laid out easily like on the piano.

This Collings SoCo Deluxe is Sexton’s No. 1 guitar on tour because it stays in tune through the many chord changes of a Dylan set. It has a “dog hair” back and neck finish, a black-finished spruce top, and ThroBak SLE-101 PAF pickups.

Photo by Tim Bugbee

Was playing Townes Van Zandt in Blaze a difficult role, having known him and growing up entrenched in the Austin music scene?

Yeah, it was tricky. When Ethan [Hawke] first called me about the project, he asked, “Hey, what do you think about a movie about Blaze?” This was before my actual knowledge of Sybil Rosen’s book, which honestly balanced out the whole film. It would’ve been much different if it was just those two maniacs [Foley and Van Zandt] throughout the whole film [laughs]. It was wonderful because it needed that perspective from Sybil’s book.

Originally it was daunting. That’s the first thing I told him: “Well, those are hard to make, because of the music stuff.” There’s a bunch of bad music films like that, you know? And he said, “Will you help me put it all together?” And I said, “Yeah, of course.” And then he goes, “Well, I also want you to play Townes.” And I was like, “Uhhhhh, well that’s really terrifying.”

Because you knew Townes personally, right?

Well, it’s that because I did know him. I’m really good friends with his son. It’s a family friend, and it’s someone truly iconic, you know?

Did you feel like you had to get the family’s blessing?

That’s a whole other issue. The first call I made after that was I called J.T. [Van Zandt], his son and just said, “Hey, good news and bad news. My friend Ethan wants to make a movie about Blaze.” He said, “That’s awesome! What’s the bad news?” I said, “I’m gonna play your daddy.” He goes, “Well, that’s cool. You know I wouldn’t want anyone else but you to do it.”

Their blessing is a really tricky thing, because you can’t go into something like that to do the work with too much social stuff. Ultimately I knew there were things that were really important that needed to be correct, certain little things about him. But it was gonna be tricky, because he’s truly iconic—there’s a lot of layers to who that guy was and, in the scheme of things, I didn’t really know him. Digging in the holes I found out more things that I didn’t necessarily want to. I had to have some sort of personal understanding about maybe what he was going through as a human, which became a little too familiar [laughs].

Why did you want to help tell Blaze Foley’s story?

There’s not really a number one reason—there’s a bunch of number ones. The first thing is, I know how much regard and heart that Ethan has if he’s even calling me to ask, “What do you think, should I do this?” Because he has such high regard for music and the artistic creative process in those people, he has a lot a love and respect for that. Even though Blaze was horrible. My brother and I had the same experience with Blaze, which wasn’t pleasant. As my brother said, “I just love Ben. He showed this other side of Blaze that no one got to see.” That’s kinda true.

And honestly, for what those guys did with their creative life, there’s a million people that don’t even have a clue who Blaze was, so I thought it was important to do that for his story. And there’s still heaps of people that don’t understand or haven’t heard what Townes brought. Everyone knew who Buddy Holly was, or Jim Morrison, or whatever, so this was below the radar in a lot of ways for a lot of people. It all worked out really well because I think it showed this other side of Blaze and it keyed people into those songs that both of them had written.

Guitars

Collings SoCo Deluxe

Custom S-Style (with Chandler lipstick pickups, built by Austin Vintage)

Gibson Ron Wood L-5S

Trussart Steelcaster

Trussart Baritone SteelMaster

’55 Les Paul Custom Black Beauty

Shyboy T-Style

Gibson Trini Lopez reissue

Gretsch White Falcon Stephen Stills

Glaser T-style B-Bender

Burst Brothers ’58/’59 reissue Les Paul

Fraulini Leadbelly 12-String (acoustic)

Gibson Advanced Jumbo (acoustic)

Gibson J-200 (acoustic)

Amps

Magnatone Varsity Cathedral

'58 Supro Coronado

Effects

Electro-Harmonix POG

TC Electronic Chorus Flanger (modded by Bill Webb of Austin Vintage)

TC Electronic Nova Delay

Sarno Music Solutions Earth Drive

Fulton-Webb Textosterone

Durham Sex Drive

Strings

GHS various sets

Was the record label you launched with Ethan Hawke and Louis Black something that happened later, after the film wrapped?

That happened completely post. Basically, this project had so much synergy, it was kinda creepy. Once we finished the film, Ethan came to me and said, “I want to give Ben something else besides the film that’s his own. Would you be interested in making his record?” I said “Yeah, I’ll totally help you do that.” Ben sent 20 to 30 songs. The synergy train just kept rolling, with or without us, almost.

What was it like in the studio with Ben Dickey, having already worked on the film and then producing his original music?

It was really easy, really creative, and good. He had decent demos of the songs we were cutting, and it was a really small crew. Ben was so solid. Without it being machine-like, we were just knockin’ ’em down. I extracted a dozen songs from a batch of 20 to 30. He had some really great songs. I loved a line he would say when certain lyrics would come up, “Oh yeah, facts.” It was really funny, because a lot of it is based on his life living on a cotton field in Louisiana, dealing with nature, storms blowing down barns, hiding in the closet. Ben’s a really interesting guy. As Ethan says, you never know who’s got an interesting story. He’s done everything: been a chef, been a mover, been in bands, been default Clinton campaign security.

How did you get into producing?

It really all began when I first left home. I was 13 and I had a little band, but I also had a side band that I played drums in. We were gonna go in the studio and record songs, and right before we went, the bass player quit. So we cut recordings of the drums and guitars, and then I put bass on it later, and then I started figuring out how to put the rest of the songs together.

I was so interested in records growing up. I was listening to these records that weren’t necessarily folk records. It was kind of attached to writing. It was just in my head … I always heard the whole thing. Sometimes it was difficult to finish a song until I got all the other ideas out of the way so I could focus on lyrics and those kind of things.

So, over the course of years, prior to officially being a producer, I was always making tracks to write songs to. Or if I was cowriting, we’d do a recording of a song. It was kind of the Malcolm Gladwell 10,000-hour concept. Without even focusing on it, I was working on my 10,000 hours of recording and building tracks and figuring out how things worked.

Did you get your 10,000 hours in yet?

I never really got the count. I think you’re supposed to know what you’re doing by the time you reach it, so maybe I haven’t reached it yet because I’m always learning in that regard.

This is what it is: You have to have the balance. What’s the balance? Arrested development and always-forward movement and growth. You have to have a certain amount of arrested development that keeps you from giving up [laughs]. And then keep working and learning. You kinda stop evolving yet continue to evolve all in the same breath. You just have to know when to send yourself to your room or your corner, ya know? [Laughs.]

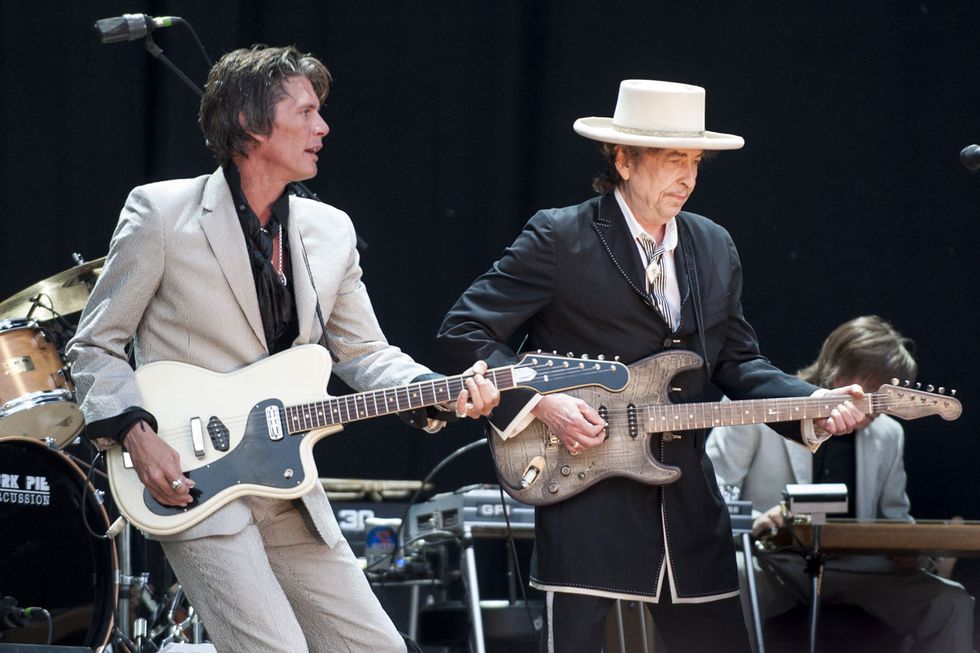

Onstage with Bob Dylan circa 2010, Charlie Sexton plays a ’60s Italian Eko with a custom exact duplicate neck made by Ed Reynolds of Austin, Texas. Meanwhile, Dylan wrangles a Trussart Steel-O-Matic. Photo by Jordi Vidal

Besides working with Dylan, what were some of the memorable sessions you’ve been a part of?

Oddly enough, I learned a lot about guitar from Edie Brickell while producing a record for her. She started taking guitar lessons years ago. She never played that much guitar, but it’s in her nature to do it herself and learn. For the first record we did together, genre-wise it was somewhat vast, and I got to see what she learned over years studying with someone. She was fingerpicking a style of acoustic; then she had a batch of songs where she was learning jazz chords. I would go through 40 songs of hers where she was doing things I hadn’t really done yet. She’s brilliant at coming up with guitar riffs. She’s unbelievable. I did two records with her [2003's Volcano and 2011's Edie Brickell.

When you’re in the studio with Dylan, when it comes to guitar parts, do you share ideas?

It all comes from him. Unless you’re really a musician and keep your eye on the ball, people don’t really understand that. As great of a lyricist and songwriter as he is, his melodic sense and everything about the musical aspect of it is just stunning. I’ve never, ever worked with anyone who has such constant ideas and fearlessness. He’ll take on something and flip it on its ear, its head, whatever and just completely reimagine it. As great as the lyrics are, the other side of it is as stunning. I’ve learned a lot over the last few years once we started making the standards records—which were five records, about 50 songs with almost 50 chords per song. All those records were done almost completely live. You kinda gotta know it all. Everything comes through that door whether it’s orchestral or country or blues or gospel or bluegrass or rock ’n’ roll.

If you’re at home working on music and writing, is the guitar what you would use as your tool?

Yes and no. Usually it’s the piano. The way it’s laid out and the fumbling about it is where you come up with voicings and substitutions. It’s laid out better than a guitar. If I had the luxury of actually knowing what I was doing, it’s all theory. I tend to stumble upon it.

Is there an instrument that you don’t play?

Sure! All of ’em [laughs].

I’ve read that you’ve been working on a three-part project over the years. Have you been working on your own music?

Yes and no. Basically, the three-part thing comes from…. It’s a funny thing—who I am depends on who you ask. Years ago, there were two projects I was going to be involved in. On one project they said, “Oh he’s not right—he’s too country,” or something. And then on the other project, they said, “No, he’s too pop.” Or bluesy. It was like depending on what they were aware of … that’s where that whole concept came from. And also it was a bit of a creative trick not to paint myself into a corner, which unfortunately, I spent more than half of my life painted in that corner being on major labels.

You played a Collings SoCo for a good part of Dylan’s last tour. Are you still playing that guitar?

Oh yeah. It’s been in the lineup since I started playing with him, really. Particularly on the last five records. It’ll play in tune. I became aware of Collings and met Bill [Collings], who brought me into the fold when he was trying to get electrics out there, which was a relatively new inclusion to the line, since he made acoustics for so many years. With so many chord counts, I was having problems with playing in tune. The second I switched over to that guitar, it took that problem away. Bill only made great instruments.

What is the current electric guitar that you play the most?

There have been some changes, since on this tour we have to do standards. On the previous tour it was 90 percent the Collings. The basic lineup of what’s in the rack is what’s been there, except for two new things that showed up. I have a lipstick Stratocaster, built by my friends at Austin Vintage. It has Chandler lipstick pickups, and is a copy of my main Arc Angels guitar. Then I have a Glaser B-Bender Tele, a Trussart Tele, a Burst Brothers ’58 reissue Les Paul that’s 10 years old, and a ’55 Les Paul Black Beauty.

I have two new things that showed up last year: a gold Shyboy Tele, based on the original Tele Snakehead design with no pickguard and a different volume. And the Ron Wood L-5 model. They only made 20 of this certain one back then, and Keith Richards bought two and kept one and gave one to Woody.

We were just in Tokyo and we went to this place we always go that has tons of Gibsons. I’m like the tester. Everyone says, “play this one.” They had the Woody guitar, and I saw it and remembered that Gibson released it. I plugged it in at the very end after I played umpteenth guitars for everyone. So I’ve been playing it a lot over the last two tours. It’s odd looking and it’s not a very common guitar. But it’s really great. My tech makes fun of me: “It’s kinda like that banjo guitar that Bela Fleck has.” Which led to him immediately photoshopping my face and superimposing it to Bela Fleck’s body [laughs].

What are some of your favorite guitars that you play at home?

There’s a crazy, cool guitar we actually got at the same shop in Japan. A signature model Les Paul Jr. goldtop that has a pickguard that looks like the one on Scotty Moore’s guitar. It looks like a Billy Gibbons guitar. Then there’s one of my Trussarts in a Jazzmaster style that we added a third pickup to and just converted it to a baritone, and it’s amazing. I’m babysitting a ’53 goldtop Les Paul that’s amazing. I used it all over Ryan Bingham’s record. We needed a slicey-sounding overdub guitar and it became the one.

Do you still play your Sex Drive pedal a lot?

Oh yeah, it’s always there. That’s the first thing that gets hit on the board. Then I’m using those Magnatone Varsitys, which I think I’m one of the few people that actually use. But it’s amazing.

When Ted [Kornblum] first introduced the line again, he brought everything down to a gig and the Varsity Cathedral was my favorite-sounding amp in the line. It looks like an old radio. People ask, “What is that behind you, a record player or something?” No, they’re amps! [Laughs.]

If music had an odor, what would yours smell like?

Oh my god. A lingering scent in the kitchen. Maybe it’s not very appetizing, but it’s maybe that strange buffet of New York where they have everything, but I’m hoping it’s better than that, unless prone to food poisoning [laughs].

What’s one of your favorite Dylan songs to play on the tour right now?

There’s this side of him where he does these sort of balladeer, crooner, creepy songs. The irony of him, with all of the discussion and debates about his singing, is he’s an amazing balladeer. Those songs are so fetching because he’s a wonderful singer and the phrasing…. I enjoy those a lot. Rock is a trap. It’s a big trap, where most people that think they’re really rocking—they aren’t. It’s like, “no stop it.” I think a lot of it has to do with the fact that roll has been excluded from the equation.

That works both ways, because if you just have the roll…

Yeah. That’s the way I look at making records. There’s not just one frequency. Your cat may scratch you and bite you, but it’ll also sit in your lap and let you pet it.

Charlie Sexton performs with Ron Wood of the Rolling Stones in 1987. Charlie’s brother, Will Sexton, played bass during the sold-out show, which was at the Hard Rock Café in Dallas, Texas. Check out their rendition of “Honkey Tonk Women” starting at 3:40.

Check out some of Charlie Sexton’s original music from a solo concert he played in 2017 at the Kessler Theater in Dallas, Texas. Don’t miss the 70-second guitar solo starting at 5:28.

Photo by Rett Peek

Smells Like Raspberries

When Charlie Sexton and Ben Dickey starred in Blaze, the two guitarists formed a bond they carried into the studio. Sexton produced Dickey’s new album, A Glimmer on the Outskirts. An astute songwriter and guitarist in his own right, Dickey told PG his intention was to make an album that “provides a notion of hope and wonder.” Here, Dickey discusses the project through the lens of guitar.What’s your and Charlie’s relationship like?

When Ethan and I first talked about who was going to be Townes Van Zandt, I was like, “Charlie, without a doubt.” He’ll take care of all these people in the story and, lo and behold, what I didn’t really know is that he took care of me.

We became fast friends. I’ve always admired his musicianship, but he’s a wonderful person. We didn’t talk about making an album until much, much later after the movie was totally finished. I was over the moon! When I sent the demos, I was nervous. When he wrote me back that he liked them, I was excited.

We never rehearsed with the band. Charlie totally produced those moments. My heart swelled. It was incredible watching him work. He’s an incredible guitar player, but he’s a musician top to bottom. I learned so much from him just watching and listening. Every time I’m around him I tap him to tell me why XYZ and he helps. He’s also someone who’s still learning and he doesn’t hide that.

How did you approach guitar on the album? Were the parts written beforehand?

My demos had all the parts written, but I wasn’t married to any of them. Most of Charlie’s leads are not note for note my stuff. He’s paying ode to the demo but he’s doing his Charlie Sexton magic so he’s doing his own thing. There are specific runs I needed coming in and out, but otherwise I told the band to just play in the spirit of it. There was never a moment where I was like “don’t do that,” because everyone was so good.

How much was Charlie playing leads?

He plays 80 to 85 percent of the guitar on the record. He will tell people, “If you go listen to the demos, that’s pretty much what Ben’s doing.” There’s a mild map for what I was intending to do, but Charlie went off on his own thing.

What’s your favorite guitar?

My grandfather passed away when I was 10, but he gave me my first guitar. He gave me this black 1935 Gibson L-30 with white trim. He would let me play it under supervision, but he got terminal cancer. He very ceremoniously took me in the den one day. He was a very eloquent man. His words were: “I’m not going to be here much longer and I know you know that and it’s hard to talk about, but I want to give this guitar to you. This is yours now and you need to take care of it.” To me, that felt, in my young brain and to this day, like a very Excalibur-ish moment. This guitar is magic, my grandad is magic, this thing will take me places. It was a little bit of a life raft, too. My folks got divorced, and we had some rough times and I clung to the guitar pretty tight.

I still use that color motif. Now I have a 1988 Gibson Chet Atkins Country Gentleman that’s black with white trim, and Gibson sent me these new ES-235s in black with white trim. It all goes back to my grandad.

Were there any guitars that Charlie had that you used in the sessions for the album?

He has a black with white trim Trini Lopez that was used on most of the leads.

I heard that you started putting acrylic on your nails for playing. Do you still do that?

I do. I picked that up from Charlie. They’re pretty strange, but they don’t break, man.

Every time I play guitar with him, I learn something. There’s little truths about guitars that guitar players know, like where your hand is on an acoustic guitar will make different sounds close to the bridge. I know those to degrees but, watching him play and what he applies…. I used one pick my whole life. He uses all sorts of picks applied to the song and I’ve never thought about it that way. The Country Gentleman is the first guitar I’ve played that has a master volume, and I had an epiphany with that.

Being with Charlie, there are so many more routes to take and branches to understand and ways to get things out of different instruments. The track “Sing That One to Me” has a unison acoustic thing, and I was listening to him accent different strumming patterns. I realized the effect of what he was doing made it swing. His ears are hearing 20 different options at once, and he knows how to draw the ones that turn things on their head or provide a different rhythm.

Compared to working on the movie, how was the studio dynamic different or the same?

It was different, because you’d be hard pressed to find me when I was making the movie. I was somewhere else. Blaze and Townes were there.

If your music had an odor, what would yours smell like?

Haha! That’s a great question. I’m gonna say mine would probably be the smell of the [cannabis] flower mixed with raspberries and lilies. I say raspberries because I read that the entire universe smells like raspberries. It’s based in science that when supernovas happen, the remnant gases that burn off lead to a very sweet smell. That’s exciting, right?

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)