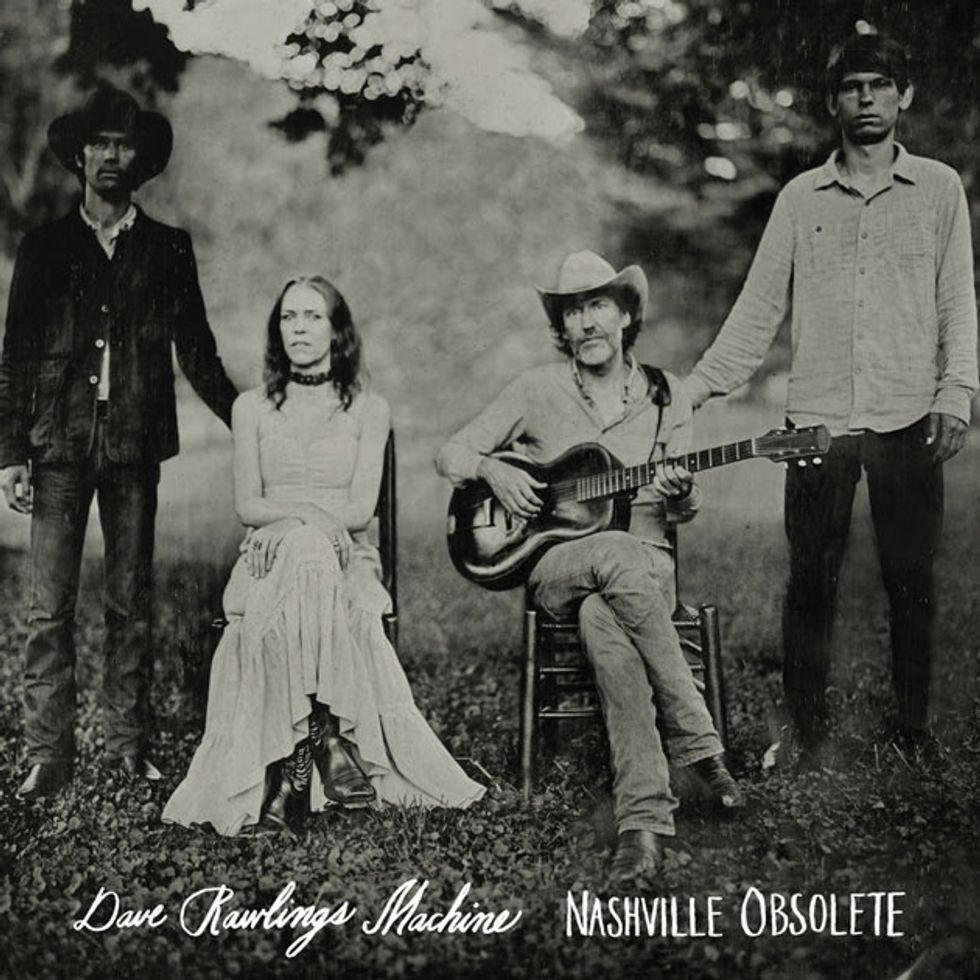

Ghosts glide and whisper everywhere in the music of David Rawlings and Gillian Welch. And it’s been that way since 1996, when the duo made the transition from respected Nashville songwriters to revered roots-music performers with Welch’s debut Revival. Through all their subsequent albums—five under Welch’s name and a pair, including the new Nashville Obsolete, under Rawlings’ solo nom de plume David Rawlings Machine—two things have remained constant: their twined voices and guitars, and those ghosts.

The spirits of the past have never been more present than they are in Nashville Obsolete’s “Bodysnatchers,” where Rawlings channels the Devil-obsessed Mississippi blues pioneer Skip James in his keening tenor singing. The spare pace of the guitars evokes the quiet of the plantation-era Delta at midnight. A moaning violin cuts the stillness between verses like a night bird crossing the moon, and the lyrics—filled with breath by the couple’s trademark close harmonies—spin a web of voodoo, soul-selling, and murder. If “Bodysnatchers” isn’t the perfect Southern Gothic creeper, it’s close.

But as fixated on sadness, loss, damnation, and missed opportunities as many of the Grammy-nominated duo’s compositions are, you’ll also find joy in these refracted tales from America’s past. The jig “Candy,” for one, grabs the sweet promise of life in a rural town just after World War II—a time when bluegrass was born from the melting pot of British and Appalachian folk music, blues, jazz, and chiming string bands.

Rawlings and Welch first crossed dusty paths as students at Boston’s Berklee College of Music, where they formed their songwriting, performing, and romantic partnership after meeting at an audition for the school’s only country band. Born in the small colonial town of North Smithfield, Rhode Island, Rawlings fell under country’s spell in the ’70s.

“That music invaded the AM and FM radio stations to some degree, so I heard story songs and country songs since the time I was 3 years old,” he says. “I remember hearing Jim Croce, and Kenny Rogers with ‘The Gambler.’ Those songs came out of the American folk music tradition. I’m also sure that as a kid I heard ‘John Henry’ somewhere. Songs like that pulled me in.”

So did the guitarists who played them. But unlike many 6-string-fixated Berklee students, Rawlings developed a highly personal sonic perspective. The subtleties of jazz hornmen Miles Davis and Chet Baker stoked an interest in unusual intervals and subtle dissonant touches that enliven harmonies. And his guitar instructor, Lauren Passerelli, helped Rawlings bare the secrets of the mountainous multi-tracked tones of the Smiths’ Johnny Marr, another of Rawlings’ heroes.

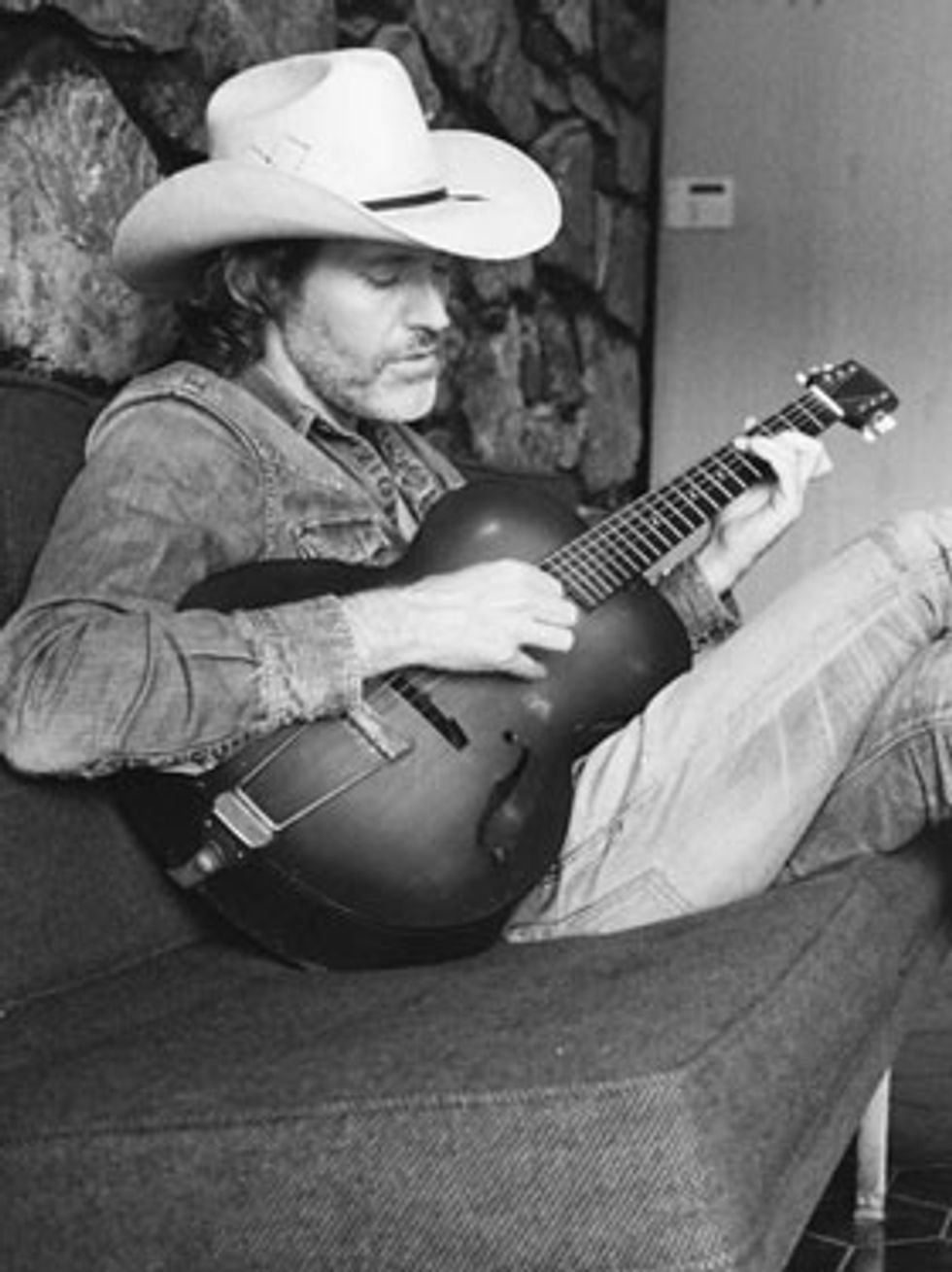

Guitarist David Rawlings met his musical and life partner, Gillian Welch, when they were students at

Berklee College of Music. Photo by Henry Diltz

That opened Rawlings up to the world of textural music informed by harmony. And that world is where he and Welch have resided ever since. It’s the key to the rich vistas their blend of voices and guitars paints on Nashville Obsolete and elsewhere.

“I think of myself as an arranger who happens to play guitar enough that I have passable technique,” Rawlings allows. “The blend of Gillian’s guitar and my guitar is an arrangement in itself. My guitar playing is built to work with her guitar playing. Without her, I don’t know what you’d have left of me. If I started working with a different guitarist, I’d probably have to change my own playing to make it fit.”

Recorded in the duo’s Woodland Studios in East Nashville—a legendary facility with a long history of recording classic country hits—Nashville Obsolete was a mantra for the duo before it was an album title. “It crosses our minds that virtually everything we do and every tool we use is obsolete,” he observes. “The microphones, the tape we record on, the tape machines, and even the recording studio is obsolete because music is no longer supposed to be something you should spend any money making, because you can’t make any money off of it. Nashville Obsolete was a phrase we’d kicked around for a long time, so we thought it was appropriate for this batch of songs.”

We dug deeper into the making of the album when we spoke with Rawlings on a recent sunny day in Nashville.

How do you record your acoustic guitar?

The method that Matt Andrews, who has engineered most of the records I’ve done, and I came up with has been gradually dialed in over the years. I’ve always used a Sony C-37A microphone—a tube microphone made in the late ’50s and early ’60s—and an old Neve 1055 preamp module.

The sound of my and Gillian’s guitars is a combination of what bleeds through the vocal mics—we use a Neumann M49, usually—and the mics we use on our guitars. We’re usually sitting close enough that every sound blends through every microphone. So the sound is a composite.

The only other constant in my guitar chain is a Fairchild compressor I bought years ago that has a particular tone. I’m not interested in the compression as much as the sound its transformers add to the chain. It gives a little point to the midrange that makes it easier to poke out from Gill’s guitar and be present under the vocals.

Rawlings developed a hybrid-picking style where he grips a flatpick between his thumb and index finger and also plucks with the nails on his middle and ring fingers. “I can’t wear a thumbpick, so I learned to fingerpick like that,” he shares. Photo by Lindsey Best

Describe your flatpicking approach.

It would all be crosspicking, at least on this record. It’s hard on songs like “Bodysnatchers” to differentiate what I’m doing with what Gill’s doing, because we’re both arpeggiating. So you’re hearing a composite. There are times when I play with a flatpick between my thumb and index finger and then will play with my second and third fingernails. I do that on “Elvis Presley Blues” [from Welch’s Time (The Revelator)]. I can’t wear a thumbpick, so I learned to fingerpick like that.

How do you decide to hybrid pick on a song?

It’s compositional, really. When I decide to fingerpick, I’m going for a particular feel I can’t get any other way. “Elvis Presley Blues,” for example, started as a minor-chord cycle and the whole thing was strummed and slower. We didn’t end up loving that. I rewrote the song to amuse myself, in a John Hurt style. Because I was playing like John Hurt, it was fingerstyle. With Gillian and me both fingerpicking, it gave the song a really natural sound. If either of us were flatpicking, that part would have sounded more like a lead guitar, and we really like the idea of the composite sound of both our guitars as the main instrumental voice for what we do.

I hear crosspicking, Travis picking, and some of Mother Maybelle Carter’s low-note-melody-with-brushed rhythm style on the albums you and Gillian do. What made you focus on those fundamentally rural techniques when you were developing as a guitarist?

My goal was to develop a style of picking that would fill in the sound for our duo and complement the way Gillian plays, which is alternating a bass line and a top string in a backbeat kind of way, and there’s space in between.

I play using crosspicking on the middle strings to fill in that space. I was never particularly good at stealing stuff from people. I had to come up with things I like that I can play. One of the only guitar players that I can point to whose licks I still might play is Norman Blake. Norman fingerpicks beautifully and flat-picks incredibly well. There are certain passages of crosspicking I learned from him that fueled my ideas when Gillian and I were arranging our first songs together.

How do you hold your pick and attack the strings?

I tend to grip the pick primarily with my second finger and thumb. The first finger is a support. I kind of hold it like a pen. I play with the back of the pick, not the tip—the fat edges. I anchor with my palm behind the bridge a little bit and my pinky is resting on the top of the guitar. John McGann in Boston is a really good flatpicker who I took a few lessons with when I was young, and he’s the one who encouraged me to experiment by playing with the back of the pick. I tried it and it gave me a really fat tone, so I immediately took to it.

You have an affinity for dissonant intervals and passages. What drew your ear to these sounds?

I don’t really think of it as dissonance. Those notes sound pretty to me. Some people think I do this to put a fly in the ointment, but I don’t. I’ve liked that kind of sound for as long as I can remember hearing music. When I was at Berklee learning about harmony and the language of music, I was happy to learn the names for it. Like, if I’m in a minor chord, I like the sound of that 9 playing against the minor third and making that minor second. I also learned I liked the sound of an 11 on a minor chord really well—a wider interval than might commonly be used, or to use the fourths and fifths more than the thirds and sixths if you’re singing with somebody, and letting that stretch things out. I often think of those things visually, envisioning an arrangement as a panorama. I think about making sounds “wide” and me and Gillian stacking up notes.

Dave Rawlings' Gear

Fretted Instruments

1935 Epiphone Olympic archtop

Early ’50s Gibson F-12 mandolin

Strings and Picks

Martin Darco 80/20 Bronze light gauge strings (.012–.054)

Fender heavy picks

Gillian Welch’s Gear

Guitars

1956 Gibson J-50

1939 Martin D-18

Strings and Picks

D’Addario EJ17 Phosphor Bronze medium strings (.013–.056)

Vintage tortoise shell picks

Do you use open or alternate tunings?

I don’t usually. I like to find fingerings in standard tuning that make people think I’m using alternate tunings. Other than dropping an E string to a D, I haven’t often gone far down that tunnel. To me, getting into an alternate tuning was playing mandolin.

So let’s talk about your mandolin, which plays a prominent role in several songs on Nashville Obsolete.

I always wanted one and enjoyed playing them, and finally got a mandolin I like, which is an early ’50s Gibson F-12. It took some time with the tuning [four courses of doubled unison strings, G–D–A–E], but I do like that my ear is what’s always pulling me. I was switching back and forth on “Pilgrim,” between the guitar and the mandolin, trying to figure out which instrument worked, up until the moment we cut it. I liked the way the mandolin made the song move, so I went with that. But the solo at the end just sounds like me making the same choices I would make on the guitar. My attempts to play differently by playing other instruments don’t often work. When I play organ, I usually find I play the same notes I would play on the guitar.

How do you and Gillian determine which of you will cut the songs you write together?

We don’t have to think about it all that much. When we were first working on songs, we’d both be singing them as we wrote, but in the end Gillian took all of them because she’s just such a great singer. We’re more concerned about the songs moving us than who’s going to sing them. Even in our earliest days, when people like Emmylou Harris and the Nashville Bluegrass Band were cutting our songs rather than us, we considered a song to be its own creature. We thought about it more like songwriters than performers. You’re trying to create this thing that, if it’s worth its salt, is not going to need you anyway. You do want to be the best vehicle for the song. That’s the dream as a performer. But I think it’s good for the song that you don’t make that the most important thing.

You play Hammond B3. What other instruments do you play?

I play drums, although not very well. I have a couple fills I do okay. My greatest honor as a drummer is that John Paul Jones had me play on a track he was producing for [songwriter] Sara Watkins. I played bass on Ryan Adams’ Heartbreaker a little bit. I’m not a great bass player, but there are certain feels I can get away with. I play a little lap steel, and a tiny bit of fiddle. I played saxophone when I was a kid and can still play a bit of that. I can play a little piano, relying on musicality rather than technique. It’s the same with the B3.

Most guitarists think of vocals as their weak card, but you and Gillian seem to harmonize effortlessly while doing some complex, intertwined picking. How did you arrive at that place?

“Practice” is the easy answer. The earliest part of learning to sing harmony is singing along with records. When I was a kid in the car listening to music, I would always add a tenor or baritone part.

There was a time when, if a song was complicated vocally, like “Long Black Veil,” one of the first songs we sang together, I didn’t play guitar. Gill played guitar and sang lead and I concentrated on a good harmony part. The key is to not do more than you can until you can. The fact that we think of the notes we’re both playing on guitar and the notes she’s singing and I’m singing as one thing has really helped us find the harmony that sounds natural. But after all these years of performing with Gillian, I can tell you I’m a way worse tenor singer than I was when I was 20 years old, and a way better baritone singer. My ear naturally pulls me underneath now, because that’s where I’ve been living.

YouTube It

In this recent clip, performed immediately after accepting a Lifetime Achievement in Songwriting from the Americana Music Association, David Rawlings displays his penchant for picking and strumming the middle strings on his 1935 Epiphone Olympic. Skip to 5:15 for an expressive solo into an outro that’ll knock your socks off.

How different is your approach to electric versus acoustic guitar?

Overdrive and sustain change my playing more than anything else. I usually play flatwound strings on an electric. An old ’50s Esquire is my main electric guitar. I haven’t developed my style on that instrument as much as I’d like to. I do hear myself sounding more like Neil Young when I play electric. I considered playing electric guitar on this album, but I’ve already come far enough on the acoustic that I’m afraid I wouldn’t do as good a job without paying some dues.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)