David Grissom hit the roots-rock scene at gale force in 1985, catching the ears and dropping the jaws of guitarists and laymen alike as the secret weapon in revered Austin songwriter Joe Ely’s band. Grissom had moved to the self-proclaimed “Live Music Capitol of the World” just two years earlier in pursuit of his free-ranging muse. Unleashed by Ely, the Kentucky native hunted it with a killer blend of raw-edged tone, hybrid chops, and adopted Texas swagger.

Those qualities—plus ever-evolving guitar and songwriting vocabularies—have propelled Grissom on a creative trajectory that has yet to crest. In 1991 he joined John Mellencamp’s band for a three-year stint that concluded after an inspiring three-week tour with the Allman Brothers, filling in for troubled genius Dickey Betts. Then he returned to Austin, where he united with Stevie Ray Vaughan’s Double Trouble rhythm section and singer Malford Milligan to form Storyville, a blues/rock/soul combo that cut two major-label albums, won nine Austin music awards including Best Band, and shimmied into the arena and shed circuit thanks to widespread rock radio airplay.

Meanwhile Grissom worked as a session and stage hired gun, touring and recording with the Dixie Chicks, Ringo Starr, Chris Isaak, Robben Ford, and Buddy Guy. He also became part of Nashville’s songwriting firmament, penning tunes for Trisha Yearwood, Lee Ann Womack, and others. The icing on those accomplishments was the launch of his solo career with 2007’s Loud Music on Grissom’s own Wide Lode Records label, which found him plowing a creative furrow similar to Ely’s.

Over the past seven years—and the release of two more solo albums, 2009’s country vibed 10,000 Feet and 2011’s blues-rock Way Down Deep—the icing has become the cake. While Grissom still gigs as a sideman (Buddy Guy’s Grammy-winning Living Proof is one example), he sounds fully at home in his own musical skin on the new How It Feels To Fly. The disc blends Grissom’s best and most personal songwriting with instrumental performances that duck down all kinds of stylistic alleys, including jazz and hypno-sonics, and strikes a balance between eight studio cuts and four live tracks.

The title number and “Bringin’ Sunday Mornin’ To Saturday Night” are testimonials to music’s elevating power, and the stage recordings of “Jessica” and “Nasty Dogs and Funky Kings” from Austin’s Saxon Pub—Grissom’s home base—offer tribute to a pair of his early influences, the Allman Brothers and Billy Gibbons.

“The album reflects the last two years of playing live with my own band and being at a point where I’m more focused as a musician and more content as a person,” Grissom explains by phone from his Austin home. “I’m taking more chances, and I’ve never been more satisfied than playing my tunes with this band. I’ve been lucky to have a lot of studio work in Austin with other artists, so I don’t have to get on a bus as somebody else’s guitar player.”

David Grissom's Gear

Guitars

Paul Reed Smith DGT signature model

Hamer Monaco SubTone baritone with single-coil pickups

1952 Fender Telecaster

1969 Gretsch Double Anniversary with TV Jones soap bar pickups and Bigsby whammy bar

Collings D2H acoustic

Amps

Paul Reed Smith DG Custom 30

Paul Reed Smith DG Custom 50

Effects

Psionic Audio Telos buffer and boost pedal

Xotic Effects EP Booster

Ernie Ball 6180 VP JR volume pedal

Arion Stereo Chorus

Line 6 M9 Stompbox Modeler

Strymon El Capistan dTape Echo

Strings and Picks

D’Addario EXL115 medium electric sets (.011–.049)

EXP17 coated phosphor medium acoustic sets (.013–.056)

Fender 1 mm picks

How It Feels To Fly also offers Grissom’s most bristling recorded guitar tones, generated by the union of his Paul Reed Smith signature model guitar and amps: a whammy-equipped DGT 6-string, and brand-new ultra-responsive DG Custom 30- and 50-watt tube barkers. Grissom’s also a wiz at overdubbing acoustic and electric guitar textures in support of his voice, which carries the right blend of dust and sugar to make his lyrics ring with pleasing conviction. The album favors the copacetic communication he’s achieved with keyboardist Stefano Intelisano, bassist Scott Nelson, and drummer Bryan Austin.

When we spoke, Grissom was suffering from a minor bout with pneumonia, but his spirits were high thanks to the impending March 20 start of his first major European tour under his own banner.

How It Feels To Fly is quite eclectic. What was your game plan going into the album?

I didn’t have a game plan, other than to start writing songs and see where they’d lead me. I’m really adamant about not making the same record twice. If I just start writing songs, the picture will emerge. It became apparent that I wasn’t writing a lot of instrumentals. My drummer asked a soundman at the Saxon to record one of our shows. Those performances really captured the band identity, so I felt they were a good way to balance out the studio tracks for those people that want to hear a lot of guitar playing. I love making records with other artists, but what gives me the most satisfaction is working on my own projects, and having this band together for the past couple years has so much to do with that. It seems like a long time since Way Down Deep, but so many things vie for your time—especially when you’re a one-man record company and you’re playing gigs and sessions.

You’ve toured and recorded with so many great artists. What was the most challenging or interesting gig?

The most pivotal one was playing with Joe Ely for six years when I got to Austin. He gave me freedom to step out and do my thing. He’s such a true artist with an amazing amount of integrity. I worked with Mellencamp after that. The key thing for me about working with him was watching how he arranged these folk songs into great sounding records in the studio. Then Storyville—I learned a lot playing sold-out arena shows and national TV. After I got the call to go out and play with the Allman Brothers to fill in for Dickey Betts, a lightbulb went on, and I remembered why I do this. I left John right after that—going from a private jet and having my laundry done to jumping in the van and driving across the country slugging it out. But I got a chance to hone my songwriting skills, so I wouldn’t trade that for anything.

What is your songwriting process like?

I have musical ideas for days on end. That is like breathing. The challenge is writing lyrics about something I care about. A song means so much more if it resonates through my experience. I had a publishing deal in Nashville for years and co-wrote hundreds of songs. Some were cut by big artists, but I would have put only a handful on my own records. It was an invaluable education.

Writing songs is similar to how I’ve developed my guitar style. I just sit and play. The techniques that make me recognizable all come naturally from that. I might write a hundred pages of nonsense, but the 101st page is an entire song fleshed out. I spent a week trying to write “How It Feels to Fly” and threw away 100 pages—and then 70 percent of that song came in 15 minutes.

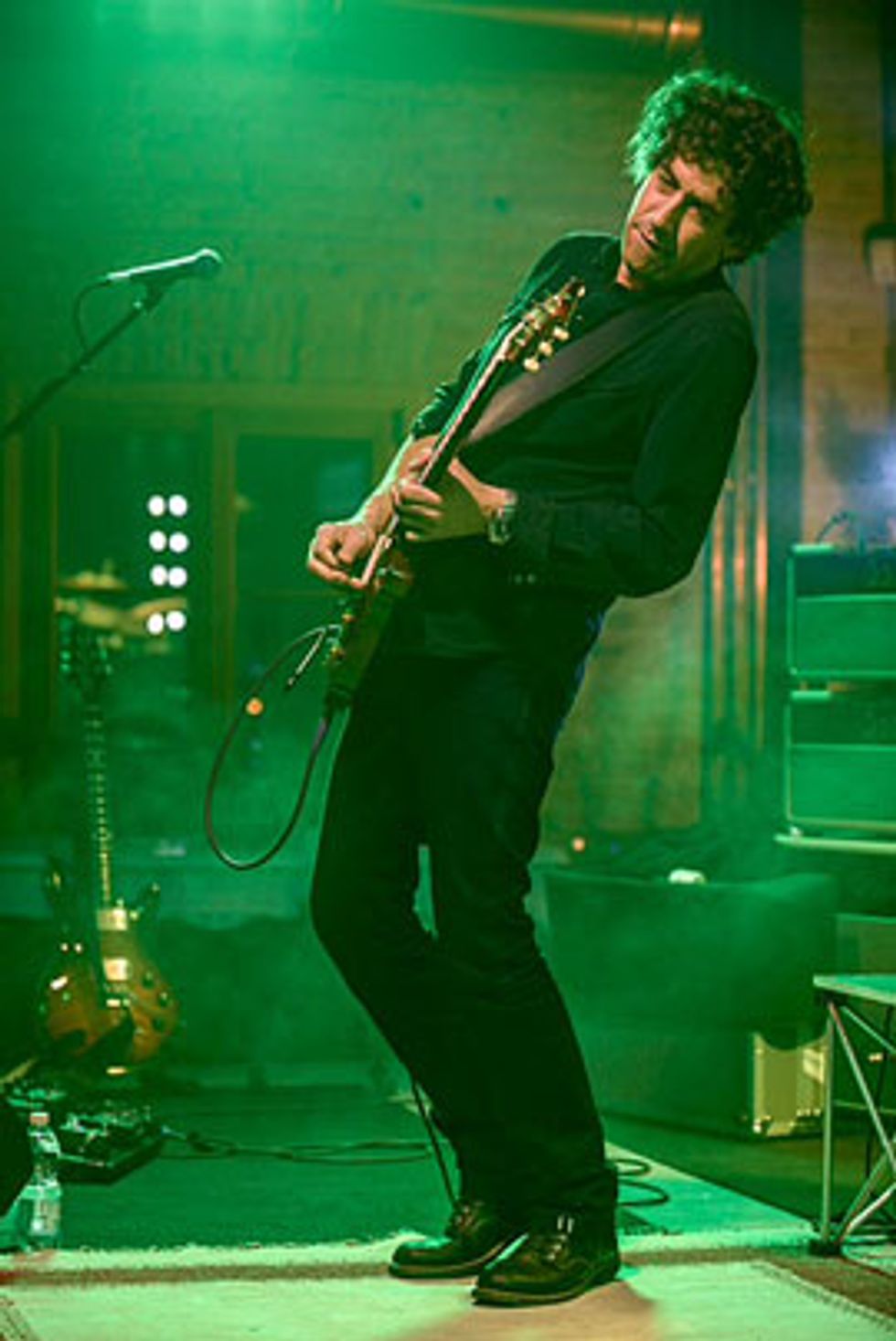

Photo by Denis Ulliana.

“How It Feels To Fly” seems to be about a personal renaissance.

It definitely is. I’ve been through a lot—some things rewarding and spiritual and some very painful. That song is about getting to that place where I accept all of it and realize the good and bad have all been necessary to get to this point in my life, where I’m feeling the most fulfilled I’ve ever been and making the best music I’ve ever made. The title also describes how I feel with my band now and the spiritual fulfillment it gives me. There are times playing with my band where it’s really stretching out … not to be corny about it, but it does feel like flying. The brain turns off and the heart takes over.

You mentioned the “spiritual fulfillment” of music. “Bringin’ Sunday Mornin’ To Saturday Night” seems to be about that.

It is. When I wrote that song, some sense of direction for the album emerged. That was one of the few songs on the record where I laid down electric guitar before the band came over. I got a fat rhythm tone I was happy with and put the vocal down over a basic drum loop. That song is about everything that attracted me to playing music in the first place. Growing up in Louisville, Kentucky, without a big music scene, music was my ticket to a deeper place. It’s also about my disregard for genres. I never thought I had to be a rock player or a blues player or a country player. It was all good, as long as it was spiritual and uplifting.

What are the differences between writing an instrumental and a song with lyrics?

My goal is to try to straddle formats with an instrumental. There’s blues and Latin on “Way Jose,” and I don’t even know what “Flim Flam” is. “Skimming the Surface,” off my last album, was built around the technique of using open strings combined with notes much higher on the neck over a James Brown groove and using interesting chords on the turnaround.

When I heard the Beatles’ Revolver and that interesting lick that comes in at about 1:30 on “Got To Get You Into My Life”—that horn line—there was a sonic thing that seemed like magic to me. So with chord voicings, the groove, the way I arrange the song and how I layer the guitars, I’m really going for a sonic thing as much as I am an actual melody.

How did you become interested in the technique of playing melodies around a drone, as you do on “Flim Flam” and other tunes?

The technique goes back to Norman Blake and Doc Watson—trying to learn to play bluegrass using open strings. Many bluegrass melodies are based around open strings and tunings. The beauty of open strings is that they have a timbre that’s different from a fretted note. So I went from this first position bluegrass thing of incorporating open strings to realizing I could play at the 12th fret and all those open strings are still valid, and as a result of incorporating them I get interval jumps that are different than if I was playing all fretted notes out of one position. Jumping to different octaves, creating drone effects—you can do a sitar-like thing or make it very rhythmic. There are times when I’m soloing where the rhythmic approach I’m taking is more important than the melodic content. Some of that is because I started out playing drums. I also try to open up the tonal palette as best as I can using pedal tones and steel bends.

Grissom's current pedalboards.

Tell us about your hybrid picking technique.

It’s a pick and two fingers. When you play that way you can strike three notes at once, as opposed to raking across the notes. I played in a funk band in high school and I was able to get that popping thing happening better with my middle finger than a pick. When I got into country I was able to add chicken pickin’. Now I might use my pick to pedal a note, say, on the fourth string and use my second and third fingers to play notes above it with a different rhythm. I can do so many different things that are literally impossible to do without hybrid picking.

What’s the relationship between your guitar and voice?

I’m a much better guitar player than singer, but I want to sing the songs that I write. I won’t rule out the possibility that at some point I might have a band with a different singer. But my singing has gotten stronger though gigging, and it seems counterproductive to go back to instrumentals. One of my jobs as a player has been to come up with great hooks for songs by Joe Ely or John Mellencamp or Buddy Guy. I enjoy being able to bring that to my own songs.

How did you create your Paul Reed Smith DGT signature model guitar and DG Custom amps?

I started playing PRS in 1985, so the guitar was almost 25 years in the making. In 1991, when I was working with Mellencamp, I wanted a PRS that had a little more low end and a little less midrange, to add a more vintage character. I collaborated with Bonnie Lloyd, who was the artist-relations person, on a bunch of changes to a stock model. They made that guitar the McCarty, which became my guitar for many years, although I always got mine with a tremolo arm. That adds liveliness and a natural reverb to the tone.

I was regularly making changes to that guitar’s fretwire, pickups, and tuners. And I would go to Nashville for sessions and put it in [Music City studio vets] Pat Buchanan’s or Kenny Greenberg’s hands, and they’d say, “Man, if I could get this guitar, I would buy it.” So I made a list of things I felt would improve the McCarty model, and Paul and I decided to come up with a new guitar.

YouTube It

Four cuts from David Grissom’s new How It Feels To Fly were recorded live at Austin’s Saxon Pub, including the jazz-blues space jam instrumental “Flim Flam.” At this Saxon show on March 27, 2012, Grissom employs several of his sonic trademarks in the tune’s epic yet tasteful solo. Starting at the four-minute mark, he uses a droning open-string-based figure to reenter after Stefano Intelisano’s keyboard break. Then Grissom dapples on some delay and rides his Paul Reed Smith DGT signature model’s whammy bar to transition into a melodic single-note passage, played with exemplary dynamics. At 6:40 he throws subtly dissonant chords into the mix, and closes with stone-cold Texas blues licks borrowed from his hero Billy Gibbons.

Tell us about the pickups.

I spent an entire year developing them. The benchmark was my ’59 ES-335, which has incredible PAFs. An almost magical upper harmonic blooms out of the note. We built a test guitar where we could change pickups in seconds, so you could really do an objective comparison. Then we took the necks of my two favorite PRS guitars—both of which were atypical due to the way the sander had finished them—and interpolated them for the neck shape. I think it’s the most vintage-inspired guitar that Paul makes.

Are we hearing your signature amps on the new album?

Yes, I used both of them. They were designed to accentuate the same vintage qualities I was looking for in the guitar. I always try to get the bottom notes to be tight and big, but let the top notes cut through and be thick. There’s a 30-watt and a 50-watt model. I use the 30 exclusively live, because it’s plenty loud. They have totally unique circuits from the ground up, so they achieve their end result in different ways. I worked with Doug Sewell at PRS for three years. He’d come down to Austin, and I’d say, “Listen to the low end of this 50-watt Marshall. Listen to the midrange of this AC-30, and how this tweed Deluxe records amazingly well. How can we get all of those qualities into one amp?” They were road tested on at least 100 gigs and 75 record dates. If I take the DG Custom 30 to a session, with the DGT’s coil-tapping sounds I can cover everything. The amps are super touch-sensitive. We achieved a sweet spot with the small amount of natural compression in the amps and their gain structure. You can go from clean to overdrive just with the attack.

How did you zero in on your trademark earthy, rooted sound?

The biggest thing that helped my direction was my lack of direction. YouTube didn’t exist. There were no video courses you could buy. I would fall asleep with the radio on at night trying to find some magic. My father had a Waylon Jennings 8-track he would play with the song “The Only Daddy That Will Walk the Line.” Waylon’s guitar solo influenced my whole country thing, and then I saw the PBS Roy Buchanan special [1971’s The Greatest Unknown Guitarist In the World]. That mixed everything up. I immersed myself in his first two records. My first guitar teacher turned me on to Keith Richards and bluegrass. My second teacher turned me on to B.B. King and Magic Sam. And my third teacher turned me on to Kenny Burrell and Wes Montgomery and taught me some theory. Then I started to go to bluegrass festivals. I also began listening to everything that was happening in Austin. When I moved here after I finished school, I started playing with everybody I’d been listening to: Lou Ann Barton, Joe Ely, the Fabulous Thunderbirds.

All that is very roots-oriented, but at the same time I always listened to a lot of Jeff Beck and still think he’s unbelievably inspiring. And I caught every Southern rock show that came to Louisville: ZZ Top, the Allman Brothers. Everything percolated. Sometimes it was just one song on a record. I got a Dave Edmunds record with “Sweet Little Lisa,” and Albert Lee plays an amazing solo with all these pedal steel bends. It took an entire year to learn how to play that solo, and later I read that Albert used a B-string bender to play it. Had I known that, I would’ve assumed you couldn’t play that solo without one. So the vacuum that existed growing up in a smaller isolated city really stood me well!

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)