Devon Gilfillian arrived in Nashville in 2013 hoping to find a career as a hot-shot hired-gun guitarist. It was a logical move. He’d grown up obsessed with the instrument after his father, a wedding singer in suburban Philadelphia, had hipped him to Jimi Hendrix while he was in high school, setting the teenager on a listening journey through the classic-rock canon. After playing in cover bands during his time at West Chester University of Pennsylvania, the ambitious guitarist had the chops to believe he could hang in Music City.

Once he settled in, Gilfillian began writing songs as a personal project. He received the encouragement he needed to take his songwriting more seriously after playing some of these tunes for his restaurant co-worker, Jonathan Smalt. With Smalt as his drummer/manager, Gilfillian recorded his 2016 debut EP, Devon Gilfillian, introducing his guitar playing, songwriting, and expressive, soulful voice via five tracks of raw, gospel-inspired, bluesy rock. Since then, he’s landed opening slots for the Brothers Osborne, Mavis Staples, and Michael McDonald while continuing to develop his sound.

For his first full-length, the new Black Hole Rainbow, Gilfillian joined with producer Shawn Everett—known for his work with the War on Drugs, Alabama Shakes, and Kacey Musgraves—and songwriter Jamie Lidell. They created an album that showcases Gilfillian’s musical evolution by drawing on the full breadth of his influences, from old-school artists such as Curtis Mayfield, Otis Redding, and Fela Kuti to the modern sounds of Kanye West and Pharrell Williams.

Gilfillian and Everett drew on creative production techniques inspired by contemporary hip-hop and R&B, going as far as cutting all of the instrumental tracks to vinyl and re-sampling them before adding vocals. The effect is a thoroughly modern-sounding album that, much like the music made by West and Williams, is able to draw on vintage soul and blues references while maintaining a cutting-edge sound. From the anthemic hooks and fat beats of “Unchained,” to the retro Afrobeat grooves that form the foundation of “Go Out and Get It,” to the electric piano-driven neo-soul ballad “Even Though It Hurts,” every song is packed with layers of sonic treats that reward repeated listening. And while Gilfillian’s guitar no longer sits at center stage, where it had in his earlier work, layers of effected guitars, funky riffs, and dramatic chord changes are essential to the sound of Black Hole Rainbow.

PG caught up with Gilfillian the morning after a sold-out show at St. Louis’ The Pageant, where he and his band had just wrapped up a tour opening for Grace Potter.

Your dad was a musician. Did he have a big impact on how you got into playing music?

Yeah. My dad’s a wedding singer. He’s been a singer all his life, and he plays percussion. He was in a band back in the ’80s called Cafe Olé, which was R&B and island music mixed with a rock ’n’ roll vibe. He was playing Stevie Wonder, Ray Charles, Michael Jackson, Donny Hathaway, and all this good soul music in the house. He was the one to share that knowledge with me when I was a kid.

I started playing guitar when I was 14. I had a buddy in high school who was playing guitar, and I thought it was rad, so I picked up an Ibanez acoustic-electric. I learned “Under the Bridge” by the Red Hot Chili Peppers and my dad was like, “This guy sounds like Jimi Hendrix.” And my dad hit me with a Jimi Hendrix greatest hits CD. After I put that in my ears, my brain exploded and I needed to know everything, and that threw me down the classic-rock hallway: Led Zeppelin, Allman Brothers, AC/DC, Lynyrd Skynyrd, anything that was guitar-centric. That was my introduction to guitar and how I started to fall in love with it.

There are a lot of vintage references on Black Hole Rainbow: On “The Good Life,” you shout out Hendrix’s “Castles Made of Sand,” and there are times where you’re singing falsetto and I hear a strong Curtis Mayfield kind of vibe. Your music still sounds really distinct from those references, though. How do you find your own sound within these big inspirations?

You have to take influences and inspirations from different places to find something new. Obviously, I love Jimi Hendrix and Curtis Mayfield, and Otis Redding and Marvin Gaye. But I also love hip-hop as well—Pharrell and Kanye and what they do and how they produce music. I wanted to take techniques they use and incorporate it into the record.

That’s what art is: taking all of your influences and trying to tastefully put that all together. If you try to sound exactly like your influences, people can tell. When you mix up a couple ingredients that people don’t usually put together, that’s when something new happens.

How do you modernize those older influences?

When we were recording, we wanted to make it sound like we were sampling ourselves. We went into this studio in Hollywood called Electro-Vox Recording Studios. It’s all analog gear—2" tape machines, beautiful guitars from the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s, all these old synthesizers. It was like a vintage playground. Shawn [Everett] is out there and he’s worked out of Electro-Vox a couple different times and he knew we’d get everything we needed there.

TIDBIT: The first step of cutting Gilfillian’s debut full-length was making an entire, separate album of instrumentals to be sampled and woven into the fabric of Black Hole Rainbow.

We pretended we were a ’70s funk/soul band and recorded all of the instrumental tracks to 2" tape. Then we got Shawn to mix it on the board there and took that mix and pressed it to vinyl. We had 11 instrumentals on vinyl and we actually dumped all of the stems to the vinyl as well so we could upload them into Pro Tools and manipulate them.

Whose idea was it to press the instrumentals to vinyl?

That was Shawn’s idea. In effect, we sampled ourselves and had this warm vinyl sound, like the way Kanye would sample Curtis Mayfield. Then, I sang on top of those tracks into Pro Tools. I sang like a hundred background vocals trying to make a choir.

We used those kinds of modern techniques that you could only use today. We also got weird and did things like spinning a microphone in front of a speaker to emulate a Leslie, or throwing water on the ground to make a splash noise so we could make the snare sound like water splashing. We went down every rabbit hole there was and I loved it. To me, that’s the fun thing about recording.

Could you tell me a little bit about the concept for the material on the album, and cowriting the music with Jamie Lidell?

Black Hole Rainbow represents my life and how it feels getting through depression, getting sucked into the black hole of life, and trying to come out the other end and get through it … not to go around the darkness but to go through it and see the light and the beauty and the colors that come out on the other end. Songs like “Get Out and Get It” and “Unchained” are songs meant to encourage myself to be a better person and get through obstacles that are damning and in my way.

For “Get Out and Get It,” I remember that day, waking up, and I was lethargic and didn’t want to do it and I had to think, “Come on man, you get to make music for a living. Get up off your ass and let’s write a song!” That was the motivation behind it. As soon as I told Jamie I wanted to get into an Afrobeat world, that inspired it even more.

Songs like “Lonely” and “Find a Light” are about being depressed. “Lonely” is a song for anybody that’s going through it—just to know you’re not the only person who’s going through depression. “Find a Light” is half written for myself and half written for people I love, and saying, “Hey, you have to do this for yourself and you have to want to pull yourself out of the dark place and no one else can do it for you.” That’s one of the biggest themes of the record.

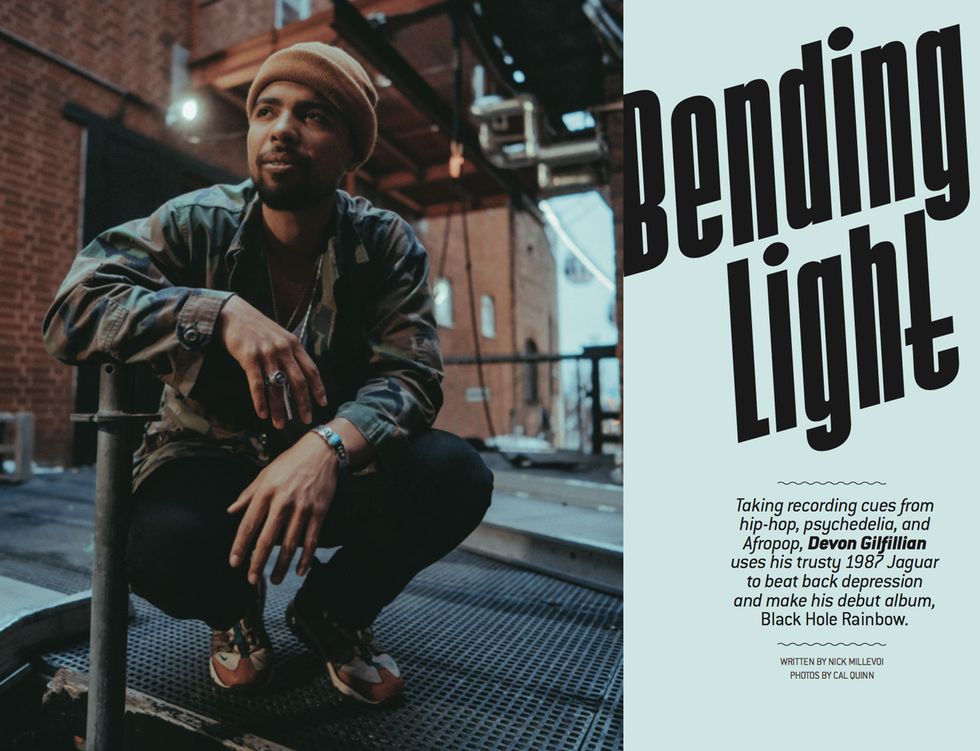

Although Gilfillian moved to Nashville to be a hired-gun guitarist, he found his place in the city’s diverse music community—and beyond—as a songwriter after meeting his drummer and manager Jonathan Smalt, when both were waiters. Photo by Cal Quinn

These are really personal themes. What’s it like working with someone else to bring this stuff to light?

It was great. Writing these songs with other people and the people I wrote them with … it felt like therapy. That’s how these songs came out of me, just spilling my guts. I think when you’re writing songs with another person, it’s important that they get you and understand you and care about you.

How did you end up working with Shawn Everett?

I fell in love with Sound & Color, the Alabama Shakes record. I also fell in love with the War on Drugs’ A Deeper Understanding. The tones and the sounds are insane. To me, they’re moving forward; they’re doing what Jimi Hendrix was doing. I found out Shawn was the engineer of those and produced the War on Drugs, and I talked to my label to see if we could get ahold of him. Eventually, I got to eat breakfast with him and told him what I wanted to do with the record, and he was in.

How long did it take to record?

We started to record in May of 2018 and in January of 2019 we were done tracking everything. It was probably four months of actual time spent in L.A.

Your song “Get Out and Get It” is based around the groove to the song “In the Jungle” by the Nigerian band the Hygrades. What inspired that?

That was inspired by Jamie Lidell. I wrote the song with Jamie and wanted to go into the Afrobeat world. I wanted to get people movin’ and groovin’, and he said, “I’ve got what we need,” and dug up “In the Jungle.” It was perfect.

That song has such a cool guitar sound and solo.

It’s incredible! It’s dirty! It’s this super plucky guitar sound. I’m in love with it. For my version, I was using this weird wah fuzz.

You traveled to Africa after you made the album. Is African diaspora guitar music really important to you?

I haven’t studied specific African guitar players, but I definitely need to. In all of the Afrobeat music I’ve listened to, from Antibalas and Fela Kuti and some other cats, the guitar tone is so raw and sometimes a little out of tune, and that, to me, gives it a different character that I love.

We went down to Johannesburg, South Africa, to shoot a music video and got some really great photos and footage. I met the artist that did the artwork for the record—this really amazing charcoal painting. It’s beautiful and it’s a wild town. I learned a lot about the growing pains of a Third World country, but also about the amazing art and music that is coming out of there. It’s so cool and really magical.

How do you envision the role of the guitar in your music?

It’s evolved over the past several years. I definitely want it to be very present. My guitar is like another one of the guys—and the tones need to be perfect.The guitar has always been an extension of me, an extension of my voice, and the way I write songs. But I also love grooves. The bass and drums are so essential for people to feel the music. Growing up, I’d always written guitar-centric music, but for this record, I wanted to break out of that and focus more on the groove of the bass and the drums, and also the songs. If a guitar solo didn’t serve the song, then I didn’t do one.

Guitars

1987 Fender Jaguar

Epiphone SG

Amps

Fender Princeton

1959 Magnatone 280

Vintage Sound Vintage 22sc

Effects

CBC Pedals The Companion fuzz

MXR Analog Delay

MXR Phase 90

Strymon OB.1 Optical Compressor & Clean Boost

Strymon Flint

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball Regular Slinky (.010–.046)

Dunlop Tortex Sharp 1.14 mm

Dunlop glass slides

What’s the story with your red Fender Jaguar?

That’s my main girl. I found that about three years ago. It’s an ’87 Japanese Jaguar. I’ve always been a Strat guy, but I wanted to switch it up and do something different. I walked into Eastside Music Supply in Nashville and that red beauty was just hanging up on the wall. I plugged it in and jumped on the neck pickup and it just has that thickness that I love. I have an Epiphone SG that I’ll use for some slide, but the Jaguar is the main one.

What are your go-to effects?

I love my Strymon Flint, also my CBC fuzz that I got off Sweetwater for something like 50 bucks, and it sounds like a horn that’s on fire! Of course, I have to have an MXR Phase 90 and an Analog Delay, as well as a Strymon compressor.

What kind of amps are you into?

Right now, I have this amp from a company called Vintage Sound. It sounds great: kind of like a Deluxe Reverb in a Princeton body with a 12" Warehouse speaker. It’s a little tone box. That’s the one I travel with.

On the record, there are a couple different amps that I use. I used an old Magnatone, I forget which one, but that was mostly what I used. I also used an old Princeton.

Did you move to Nashville to be a guitar player?

Yeah, to be a guitar player, I wanted to find out what it was all about.

And it sounds like you grew up very specifically as a guitar player. How did you discover the songwriter in you?

It was such a great discovery. When I was a kid, in high school and college, I considered myself a guitar player first, then a singer. I didn’t consider myself a singer-songwriter. I’d written some songs, but when I first moved to Nashville, I thought I’d be a hired gun and didn’t focus on my own original music.

Five years ago, I met my drummer/manager John Smalt at City Winery, where I was serving tables. I showed him my Soundcloud and he was like, “What are you doing? You need to record these songs!” And that was when I actually tried to make it happen and started writing like crazy and developing my chops as a singer-songwriter. I shifted from trying to be the best guitar player to becoming the best songwriter and take on that craft.

Devon Gilfillian and his band play a stripped-down arrangement of Black Hole Rainbow’s “The Good Life” on CBS This Morning’s “Saturday Sessions.” At 2:30, Gilfillian gives his 1987 Fender Jaguar a workout as he replaces the record’s guitar/synth duel lead with a bluesy solo that delivers a taste of his rock ’n’ roll roots.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)