While the world lay dormant under strict lockdowns, Grammy-winning singer-songwriter and activist Ani DiFranco stepped out to make a strong political statement. DiFranco and her crew went to a Shell oil refinery to film the video for "Simultaneously," from her latest release, Revolutionary Love. They were immediately arrested for trespassing. "We were just standing by the side of the road. We didn't touch any of their shit and we didn't jump a fence," explains DiFranco. "They detained us for a long time and didn't say anything to us like, 'You're trespassing, please leave.'" The matter had to ultimately be resolved in Zoom court. "They charged each of us and we all had to pay a fine. One of the kids that was working on the video with us was working for so little that it would have negated his salary, so I paid his fine."

DiFranco's defiant nature can be traced back to her childhood. She was raised in a troubled home and took solace in the guitar, an instrument she picked up at age 9 after hearing the sounds of John Fahey around the house. At the store where she bought her 6-string, she met her guitar teacher, Michael Meldrum, and not long after started playing shows with him. DiFranco has always been fiercely independent and, when she turned 15, she became an emancipated minor. She often slept in a Greyhound bus station and even celebrated her 16th birthday there. Just before moving to New York City, she formed Righteous Babe Records at 19. "I was too impatient. I want to make a record now and I want to sell it at my gig tomorrow," says DiFranco (who had just spent the whole week painting her house by herself from morning to night, because she couldn't wait for the painters to come). "At first, I just wrote 'Righteous Babe Records' on the cassettes; then it became a reality." Without a label to handle inquiries, she left her phone number, 1-800-ON-HER-OWN, on the tapes. That number also served as an activist hotline and still exists today, doubling as the Righteous Babe store contact.

"I tune my Kay like my version of a baritone. Basically, the tuning I'm working with on that guitar for a lot of songs is C to C, so it's like standard tuning but the low and high notes are at C."

Revolutionary Love marks DiFranco's 22nd album on Righteous Babe and displays an eclectic blend of jazz, bossa nova, and folk influences. Most of the songs on Revolutionary Love were written on tour just before the lockdown began and the plan was to get the music out before the election. DiFranco and her team later decided that it would be best to release the album after the chaotic November-to-January period of the election, as all media eyes were laser-focused only on the contest. Of course, its lyric themes of resistance, deception, separation, and loving survival are no less resonant or relevant now. Because of the lockdown, DiFranco couldn't fly her band to her New Orleans home studio, so she planned to use live recordings for the album. Then fate intervened, and Brad Cook, a producer friend, offered a helping hand.

"Brad said, 'Listen, if you can get yourself here for a few days, I'll put a group of musicians together and find a place,'" recalls DiFranco. She flew out to North Carolina and embarked upon a huge leap of faith. "Because of the pandemic, the lockdown had already begun and my income had dried up," DiFranco says. "I thought, 'I really hope this works out because I'm going to invest in this situation.'"

Ani DiFranco recorded Revolutionary Love at Overdub Lane in Durham, North Carolina, with producer Brad Cook. Roosevelt Collier played pedal steel on three songs from the 11-track album.

DiFranco met the musicians for the first time ever at the session, and the impersonal nature of the masks actually helped DiFranco overcome her social anxiety. "It was interesting," says DiFranco. "Of course, I had to get over the phobia that we were in a very cramped space. I was in a homemade cotton mask and sweating and trying to get acclimated to it. But after a while, I realized it was sort of comforting, especially in that situation doing something so intimate and vulnerable with strangers in a new environment. The mask was kind of a security blanket."

The recording sessions for Revolutionary Love took place over a five-day period. During the first two days, DiFranco and drummer Yan Westerlund recorded the whole album. Then, on the following days, percussionist Brevan Hampden and keyboardist Phil Cook overdubbed their parts. After the parts were recorded, pedal-steel player extraordinaire Roosevelt Collier was recruited to lend his magic touch to three songs. Collier's playing on "Shrinking Violet" was spectacular. "I was just so floored," recalls DiFranco. "I think of the pedal steel as sort of this background color, but how he approached it was much more blues, sort of like another singer. It wasn't a color in the background. He turned it into a duet, like his guitar was answering."

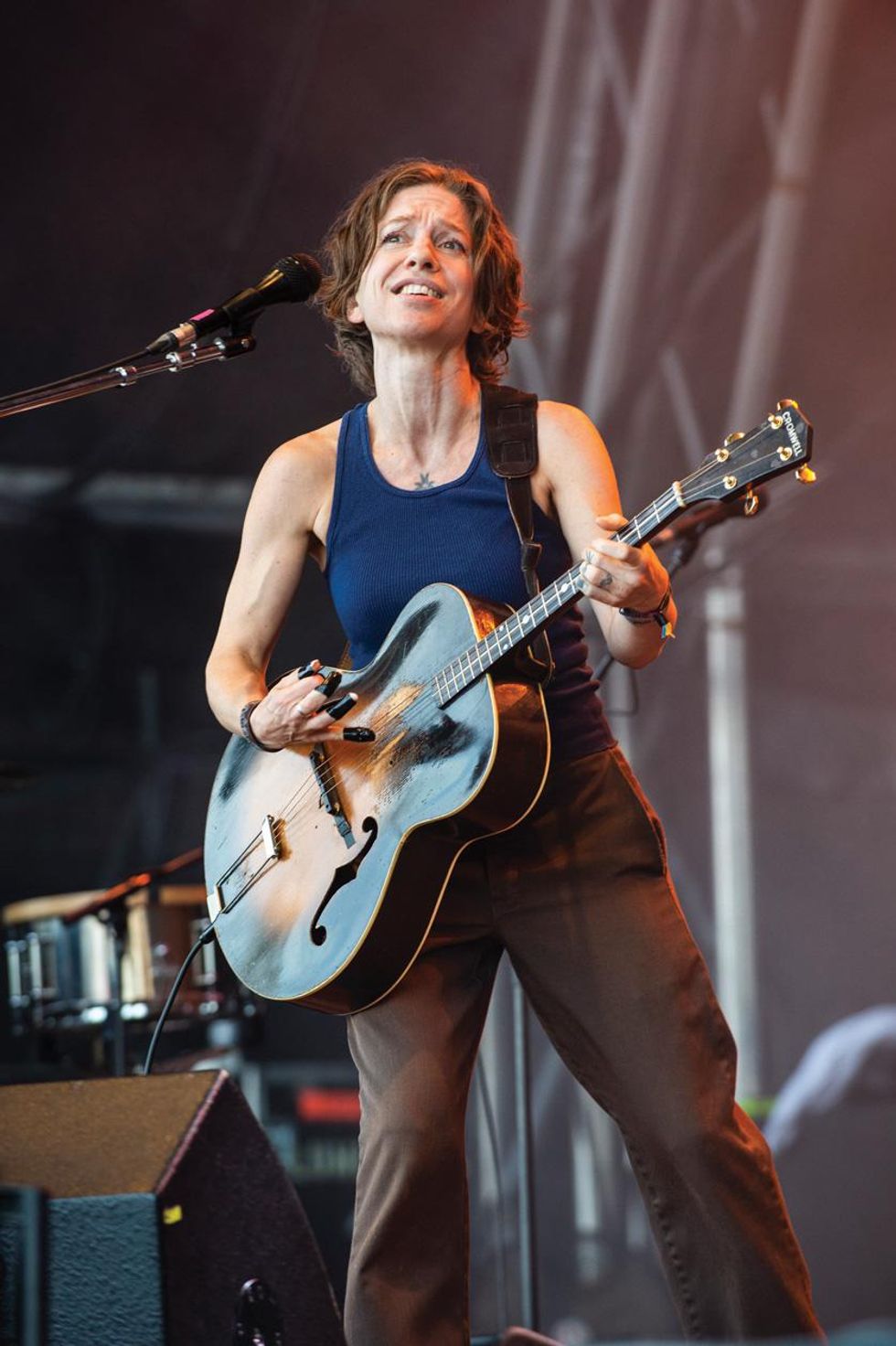

Ani DiFranco plays her 1930s Gibson-made Cromwell G-4 archtop at the 2017 Cruïlla Festival at Parc del Fòrum in Barcelona, Spain.

Photo by Jordi Vidal

DiFranco road-tested the songs from Revolutionary Love long before she hit the studio. "I'm on the road all the time and I write songs along the way, so they come out immediately," she says. "Usually, my audience at the live shows hears albums way before they're released. I do really feel that sharing songs with an audience is part of my workshop. One blessing of never being played on the radio is that there are no hits. People do have some favorites, for sure, and those make good encores or show closers. When people come to my show, they know that they don't know what they're going to hear. I determined that I have about 80 songs in my head at any given time that I can pull from."

"I do really feel that sharing songs with an audience is part of my workshop. One blessing of never being played on the radio is that there are no hits."

To keep things fresh, DiFranco will spontaneously mix and match songs for the setlists with just a moment's notice given to her very capable band. "My band was born ready," DiFranco says. "I try to lob grenades at them to see what happens. You know like, 'I want to change the keys, I'm gonna move the capo,' and I'll see my bass player just play it." Songs also morph along the way, some diverging far from the recorded versions. "They evolve over time naturally. Sometimes I forget what the chords to the bridge are supposed to be, and so they change. Sometimes I come up with new ones," she continues. "Or sometimes I'm in the wrong tuning and then I'm like, 'Oh, that's a cool color.' 'Swan Dive' is a classic old song of mine. One night I started playing it, but my high E string was tuned down to C instead of D—it's supposed to be a D for that song. I loved it and I've been playing it that way for the past few years. Things mutate."

A closeup view of road-warrior Ani DiFranco's hands show her reliance on Nailene artificial nails, which she utilizes for her captivating fingerstyle technique. She's shown here playing a set with percussionist Mike Dillon at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival in 2006

Photo by Doug Mason

In that spirit, DiFranco lets the songs progress just as organically in the studio as she does onstage. For instance, the mostly instrumental "Station Identification" was a song she and her bassist, Todd Sickafoose, and percussionist Terence Higgins, had improvised and recorded before the pandemic. "It was based on a guitar figure, once again, but then I ended up muting my guitar for most of it," DiFranco says. "You hear the guitar [sings guitar figure] come in at some point. I was actually playing that all the way through—that's what they were playing to. Then I hit mute on the guitar until a bunch of the way through. I thought I was going to add a poem or something to it, but I ended up singing a few words at the end. I thought the station identification aspect of it worked well, the way it was expressed."

Ani DiFranco's Gear

Guitars

- Kay with DeArmond gold-foil pickups and rubber bridge

- Kay parlor guitar with rubber bridge

Strings

- D'Addario XL Chromes Jazz Light (flatwounds; .011–.050 from a 7-string set)

Amps

- Carr Rambler with tremolo engaged (house amp at Overdub Lane in Durham, North Carolina where Revolutionary Love was recorded)

Effects

- None (Ani uses the tremolo from her Magnatone Twilighter in live settings)

One of the earliest pieces DiFranco learned on guitar was an arrangement of Scott Joplin's "The Entertainer," and this laid the foundation for her captivating fingerpicking style. DiFranco often makes use of chords juxtaposed against bass figures, with her low and deep tunings enhancing the resonant quality of the bass notes, particularly on songs like the album's "Crocus." "I tune my Kay like my version of a baritone," says DiFranco. "Basically, the tuning I'm working with on that guitar for a lot of songs is C to C, so it's like standard tuning but the low and high notes are at C. When we were playing 'Do or Die' on the road before I recorded it, Todd had this super-slick bass line that he was working with, but then I ended up not putting bass on that song because the guitar was so deep that it didn't leave a lot of room."

Ani DiFranco started Righteous Babe Records in 1990, when she was 19, by releasing cassette tapes with her phone number written on them. The number, 1-800-ON-HER-OWN, became an activist hotline and still exists today.

It was several years ago at the Eaux Claires Music & Arts Festival that DiFranco fell in love with a particular Kay that belonged to Brad Cook. She borrowed it to sketch out many of the songs that appear on Revolutionary Love, like the title track and the album's sole instrumental, the jazzy "Confluence." "I contemplated just eloping to Mexico with this guitar, but I returned it to him. It's a Kay that was strung with flatwounds and the bridge is wrapped in rubber. It's modded out by this guy, Reuben Cox, out in L.A. [at the Old Style Guitar Shop], and this is his thing, I guess. He puts rubber around the bridges of guitars and they end up very funky, dead, and earthy, like an old dude on a porch suddenly playing it. I went and bought an identical old Kay and did the identical treatment to it. So, it's a remake of that guitar."

Beyond funky guitars, artificial nails play perhaps the most crucial part in DiFranco's sound. When she heard that her favorite line of Nailene nails was going to be discontinued, she panicked and hoarded every kit she could find. DiFranco's dependence on them may soon start to shift, however. "I am starting to think, 'What kind of guitar player am I gonna be when these nails are gone?' It's gonna be way harder for me to get onstage with naked fingers, but I'm starting to think about playing with my actual fleshy fingers." says DiFranco. "So, I actually played this record and the release show—given it was at my home—without my talons glued to my fingers."

YouTube It

A bossa nova-influenced, two-chord pattern that loops throughout serves as the backdrop for Ani DiFranco's political message on her solo rendition of "Do or Die."

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)