Of all genres, thrash metal is one where the term “raw emotion” takes on a different meaning. It’s not, for example, raw like the voice of a folk singer baring their heart and soul in a vulnerable ballad, or raw like a live, low-fidelity recording of a blues-guitar legend’s twangs and bends. No, the rawness of thrash metal demands your attention with unflinching aggression—screams, growls, blistering guitar lines, and heart-attack-inducing drumming—and few groups in the modern heavy landscape capture that as well as supergroup Dead Cross, which consists of vocalist Mike Patton, bassist Justin Pearson, guitarist/vocalist Michael Crain, and drummer Dave Lombardo.

The band’s music drips with an incomparable kind of authenticity and visceral intensity. That vitality, you can imagine, may come easily for a band with members that helped weave the very fabric of their genre with Slayer (Lombardo), have pushed the boundaries of experimental metal with the likes of Faith No More (Patton) and Mr. Bungle (Patton, Lombardo), and made grindcore dangerous again with provocateurs like the Locust (Pearson) and Retox (Pearson, Crain).

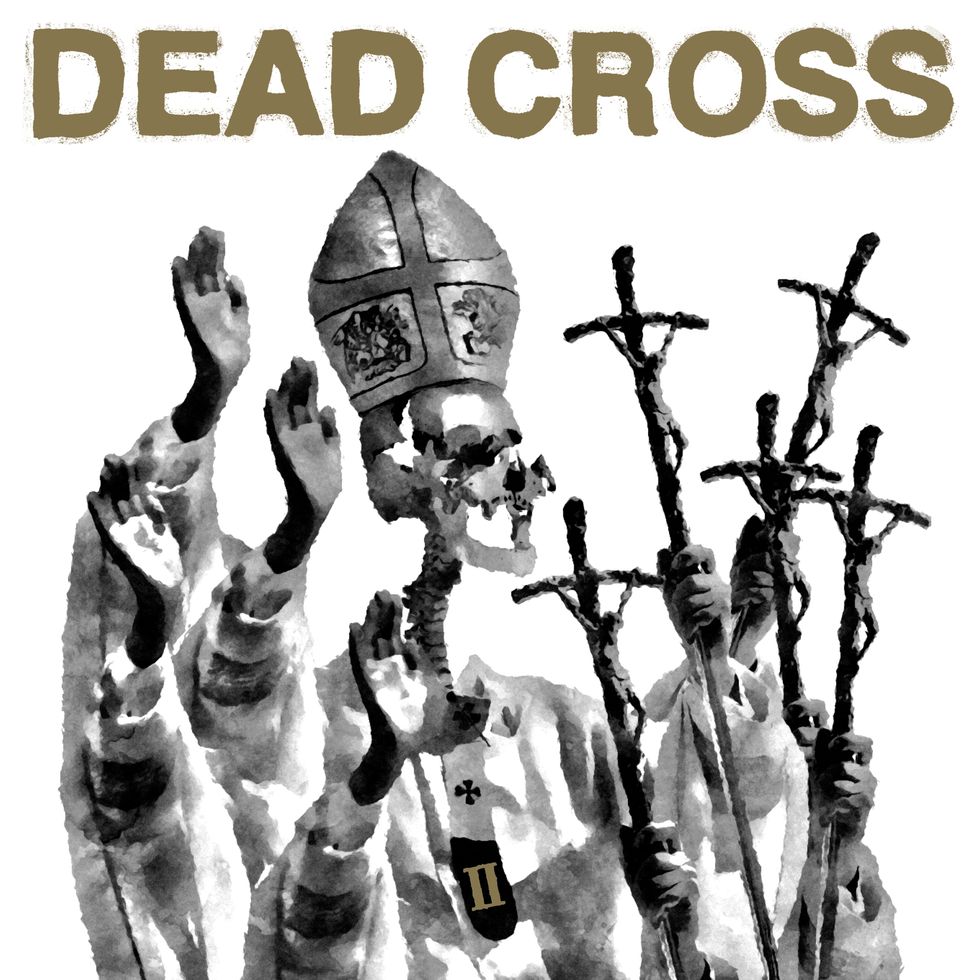

Dead Cross’ eponymous 2017 debut, produced by Ross Robinson (Slipknot, At the Drive-In, Sepultura), laid out a blueprint of chaotic and frothing metallic hardcore and outsider weirdness. It has an inimitable sound that saw its members’ distinct musical personalities coalesce into something altogether unique—all while sidestepping the classic disappointing-supergroup curse. Now, on their sophomore LP and latest release, II, the band has reunited. Joining forces once again with Robinson, they push their volatile sound to its absolute limits, dosing their hardcore punchbowl with a hearty blast of sonic psychedelics, goth-rock textures, and even more of the twisted sounds one would expect of any Patton project.

II’s songs have a palpable feeling of urgency and tension that was shaped by a series of life-altering and traumatic experiences, which included the pandemic, but also Crain’s courageous fight with cancer. “I got diagnosed in the summer of 2019 and started treatments in October,” he shares. “This was my first experience with cancer, and while head and neck cancers are the easiest to survive, they can have the worst treatments—and that was certainly my experience.”

Crain, who’s now in remission, continues, “I thought the treatments were going to kill me. Towards the end, I was so fucking sick, but I felt like, ‘Fuck this! I want to live, and I’m not going to leave anything unfinished ever again!’ So, I got a hold of Greg [Werckman, co-owner] at Ipecac and the guys in the band and said, ‘Let’s book studio time now.’ They were like, ‘Dude, are you sure? You’re like half dead right now!’ I said, ‘I don’t give a fuck. Let’s do this. I need this to live.’”

Working on a second Dead Cross record and returning to the studio with a real mission was the very thing that kept Crain going during the painful days that followed his last treatment. “I finished my last round of radiation the day before Thanksgiving, and we had studio time set up for early December,” he elaborates. “I was still very sick and in a lot of pain. It was rough to stand up for hours writing and playing, so tracking was especially tough, but that pain worked itself into the music.”

That it did, undeniably. You can feel it in the claustrophobic atmosphere and clang of “Animal Espionage,” the fuzzy hardcore stomp and acerbic delivery of “Strong and Wrong,” and the absolutely feral-sounding, bad-trip churn of “Christian Missile Crisis.”

Much of the writing and arrangement of II’s songs happened in the studio. And while Crain’s recent experiences certainly brought a lot of emotional weight to the process, working with a famously feel- and psychology-focused producer like Robinson helped tremendously to coax all of it out and inject it back into the music.

Michael Crain’s Gear

Crain’s main guitars are a ’77 and ’78 Gibson SG, classic choices which he uses to deliver blazing riffage.

Photo by Raz Azraai

Guitars

- 1977 Gibson SG Standard (with HomeWrecker pickups)

- 1978 Gibson SG Standard (with HomeWrecker pickups)

- 1970s Gibson ES-335

Amps

- Bogner Uberschall Twin Jet

- Bogner Uberschall Twin Jet 4x12 Cab

- Peavey 5150 Head

- 1970s Marshall 4x12 Cab

Effects

- EarthQuaker Devices Organizer

- DOD Rubberneck Analog Delay

- MXR Carbon Copy Analog Delay

- Ibanez Tube Screamer

- DigiTech Whammy

- Mu-Tron Octave Divider

- EHX Holy Grail Reverb

- EHX Small Stone Phase Shifter

- EHX Electric Mistress

- Boss BF-3 Flanger

- Vintage EHX Big Muff Pi

- Pro Co RAT

Strings & Picks

- Dunlop Electric Nickel (.010–.046)

- Dunlop Tortex .73 mm

Crain, who describes Robinson as the band’s fifth member, says, “He’s all about the performance and emotion.” One prime example of the producer’s uncanny ability to pull the best out of the musicians he works with is “Animal Espionage,” Crain’s favorite track on the record. Most of the song (other than the core riff and pre-chorus) was written on the spot in the studio, with Robinson coaching and pushing Crain to grasp different parts of the arrangement from places of deep emotion. “Ross is the kind of guy that asks you to think about what painful childhood memory triggered the riff for a song,” Crain shares. “He wants you to think about what emotion is actually guiding your right hand and can tell if you’re not feeling it, or if you don’t mean what you’re playing. I learned a lot about structures and arrangements, crafting parts, crescendos, and setting up moments within a song from Ross.”

That emotional attunement drives more than just their songwriting. Though Crain is Dead Cross’ sole guitarist, their music often feels like that of a band with a two-guitar assault—thanks to the interplay and synergy he has with long-term musical partner, Pearson. The two have known each other since Crain was 16, and they played together in Retox. Pearson’s performance style mirrors and dances around Crain’s in a way that’s both tight and loose at the same time, and only comes with years of mutual experience. “Justin and I have just the right combination, where we don’t share the exact same taste in music, and there’s enough difference in where we come from as musicians that it creates something unique when we work together,” Crain comments.

“I was so fucking sick, but I felt like, ‘Fuck this! I want to live, and I’m not going to leave anything unfinished ever again!’”

As for working with Lombardo, easily one of the most important heavy metal drummers of his generation, Crain has been training for the gig most of his life. “Slayer changed my fucking life, and those are totallydrum records,” he says. “Even though I’m a guitarist, I grew up around drummers; my dad plays drums, and my earliest memories were of band settings with my dad. He imparted the advice, ‘If you want to get good at an instrument, start playing with other people,’ upon me at an early age. He was 100 percent right. So, having listened to Slayer my whole adult life, when I finally started jamming with Dave, I locked in with him very quickly; I knew his playing and it felt natural.”

Lombardo’s breakneck-yet-lyrical playing certainly adds to the record’s thrash authenticity, and Crain’s love of the style is heard loud and clear on II. The dexterous riffing on “Reign of Error” is evidence of a player that’s studied the golden era of thrash deeply, and Crain confirms the influence that music has had on him in his formative years. “I really learned to play guitar when I was 16, which was during my Metallica years,” he shares. “That was when I really understood Metallica’s songcraft and their incredible abilities as players, particularly the …And Justice for All period and James Hetfield’s playing. That record was really what got me into metal playing and informed my rhythm style.”

While recovering from painful cancer treatments, Crain got himself back in the studio for the writing and tracking of II.

For the guitars and amps used to create II’s gnarly, dynamic guitar sounds, Crain kept it to a few favorites: a pair of vintage Gibson SG Standards—a ’77 and a ’78—and his ’70s Gibson ES-335. The guitars were all unmodified, aside from their custom-wound pickups, made by HomeWrecker Pickups’ Joshua Hernandez. Crain describes them as “super high-gain, but very classy and articulate.” His trusty Bogner Uberschall Twin Jet and matching 4x12 cab did the heavy lifting on the album, though Robinson’s early Peavey 5150 head and ’70s Marshall 4x12 cab rounded out the guitar sounds and provided some contrast to the Bogner.

Building on these essentials is Crain’s love of heavy guitar effects. His adventurous use of pedals twists metal and punk tropes into something less recognizable on II. Almost every guitar track on the record has some sauce on it, whether it’s a bit of percussive slapback delay in an unexpected place, spacey atmospherics as a brief respite from the violence, or warped, pitch-shifted leads that jut in and out of songs.

“The heavy flange on ‘Animal Espionage’ is one sound that inspired the riff,” the guitarist points out, and says he plugged in a Boss BF-3 for the sound. “We knew that verse was screaming for some swirl action.” He then calls out the song “Imposter Syndrome” for its “heavy [hardcore guitarist] Rikk Agnew-influenced flange setting.” Some of the album’s standout guitar moments feature Crain shifting quickly between octaves with a DigiTech Whammy, which can be heard on album opener “Love Without Love” and the solo on “Christian Missile Crisis.” Crain says he only uses the whammy pedal in the one-octave up or down position, and credits it for helping him to write many of what he considers his heaviest riffs. Also on his board for the sessions were an Ibanez Tube Screamer, an EarthQuaker Devices Organizer, a DOD Rubberneck Analog Delay, and the venerable MXR Carbon Copy, which he describes as his “Swiss-Army-knife delay.”

With countless tattoos and wearing a gas mask, Crain’s image bears a grisly, striking edge that falls perfectly in line with Dead Cross’ sound.

Photo by Becky DiGiglio

“It was rough to stand up for hours writing and playing, so tracking was especially tough, but that pain worked itself into the music.”

While Crain says he was too sick during his cancer treatments to listen to much music leading up to the writing and recording of II, his guitar influences from the goth-rock world proved to be major touchstones for his guitar sounds and compositional ideas—especially those that Agnew used on Christian Death’s records, as well as Daniel Ash of goth-rock architects Bauhaus’ sense of economy.

“Everything both these guys did was in the service of the song, and I’m a huge proponent of that,” shares Crain. “I'm not here to show off, so I always ask, ‘Is this serving the song? Is this helping the main idea? Is this supporting the thesis?’ That’s what’s important. Sure, some guitar tones or lines or players are the focal point of the song, and every song is different, but it’s about the song for me.”

Dead Cross - Church of the Motherfuckers (Live @ PBR Halftime Show)

In this live performance, Crain backs up Patton with melodic vocals and rapid-fire picking on his SG, catalyzing the furious energy that serves the Dead Cross sound.

With another Dead Cross release out in the world and cancer treatment in the rear view, Crain looks back on the process and on how the band approaches making music. While the writing and recording process was an undoubtedly painful, cathartic, and intense experience, he came away from it with more than just a new record, but an affirmation of his artistic philosophy.

“Having listened to Slayer my whole adult life, when I finally started jamming with Dave [Lombardo], I locked in with him very quickly; I knew his playing and it felt natural.”

“There should be no fucking rules. There are no rules! The one place where I don't want there to be rules or laws is fucking art,” he enthuses. “Let it be free! I love trying crazy things, and thankfully, so does Ross and my bandmates. We all love trying crazy, wild shit. Making this record is what helped me heal.”

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.