During the climax of the final piece of an ensemble concert held at a gallery in New Haven, Connecticut, guitarist Michael Gregory Jackson climbed up a stepladder so tall that an acrophobic would have a heart attack just looking at it. Once high up in the sky, Jackson let loose a bucket of ping-pong balls in the direction of the audience. “Kinetic motion, sonically beautiful, startling, if not shocking,” recalls Jackson, “The concept was to break and disturb the plane and formality—the distance between the performers and the audience. To add a little mayhem and surprise. It also sounded great.”

Even as a youth, Jackson already had a rebellious nature. “I ran away from home to see Led Zeppelin’s first American tour. I knew I wasn’t going to get permission to go, but I had to go,” says Jackson. “It was as good as I thought it was going to be. It was great. You know what I mean? They were this incredible band and it was no frills back then. They didn’t have the whole giant stage. They were just four guys up there playing music. That’s my foundation.”

Jackson’s musical horizon has significantly broadened over the decades, to the point where it now defies categorization. Vernon Reid has noted, “Michael Gregory Jackson has always cut a singular musical path on his journey through the many genres that have been his wheelhouse, through many schools of jazz, through alternative rock, and even avant-folk.” Other luminaries like Pat Metheny, Bill Frisell, and Nels Cline have also sung Jackson’s praises. Unfortunately, the more outside the box you are, the harder it is to achieve mainstream notoriety. Jackson has largely remained an unsung guitar hero for decades.

Michael Gregory Jackson - "Prelueoionti" [Excerpt from the album 'Electric Git Box']

The Pathway to a Unique Musical Vision

Originally wanting to be a drummer, Jackson picked up the guitar at age 7 at his father’s urging. He took lessons at the local music store until he was around 14, and by that point he was already impressing audiences daily in his school’s expansive courtyard. In addition to Zeppelin, his early influences were classic rock acts like Hendrix and Eric Clapton. (“Clapton is a bad word these days,” jokes Jackson.) He later got turned on to jazz giants like Wes Montgomery and Grant Green before veering off and checking out more obscure artists. “I was always attracted to different music and still am to this day. My influences are definitely not only guitar players, by any means. I’m really influenced by drummers, saxophone players, and pianists. From the age of maybe about 12 or so, I would buy two records a week completely just based on the cover art. I would not know what the music was. So, one week I’d buy Tauhid by [saxophonist] Pharoah Sanders and the other album would be [rock band] Blue Cheer. And then I would also go to the library and take out all the Nonesuch recordings and anything else that struck my fancy—like Stockhausen and John Cage. There’s nothing that I won’t listen to. I don’t like everything, but I’ll listen to it. Of course, I have my mainstays. A Love Supreme [by John Coltrane] is my Sunday morning music. To this day, I listen to it every, every Sunday. The expansive feeling, emotion, and the meditative quality of that music are really attractive to me.”

A revelation led Jackson to follow and stay true to his own musical path. “I realized very early on that I had something to say, and I wasn’t going to get to the point where I could say it by emulating someone else. I knew that Wes Montgomery was amazing, but I knew I wasn’t going to take the kind of time it took for me to work on that style of music, even though I loved it. I just felt like there’s one Wes Montgomery, there’s one Miles Davis, there’s one John Coltrane, and on and on. So, I had no desire to occupy that particular space.”

I was putting my Superman as opposed to my Clark Kent into it, you know?”

Jackson’s musical inclinations have always reflected an uncommon eclecticism. In the ’70s, he immersed himself in the NYC loft-jazz scene. Not the famed loft scene with jazz giants Michael Brecker, Dave Liebman, and Steve Grossman, but its counterpart: the avant-garde jazz scene with the likes of Henry Threadgill, Oliver Lake, and Anthony Braxton. But playing free jazz was only one facet of Jackson’s musical personality. Simultaneously, he also enjoyed and pursued other musical interests.

In 1979, he landed a deal with Arista Records as an R&B artist and recorded Gifts. Jackson’s rebellious spirit soon came to the forefront. “After Heart & Center, my second record for Arista, I thought that I’d have a deal quickly, as I knew a lot of record people. I was meeting with Clive Davis and he wanted me to be an R&B singer, which I am, but at that particular point in time, that’s not what I was interested in,” recalls Jackson. “I was told if I wanted to play jazz or R&B they would sign me, but they would not sign me playing so-called ‘rock’ music.” In those days, the music business was extremely segregated, and record labels strictly cast white artists as rockers. The record companies pigeonholed Jackson as an R&B singer, not a rock singer. Seeing no pathway for a creative outlet, Jackson asked to be released from Arista Records.

TIDBIT: “It was kind of a fight to play the music because some of it’s difficult, but luckily I’m in touch with that part of myself,” Jackson says of his new album.

“That [being an R&B singer] wasn’t my plan at that time. I was interested in the punk-rock scene and I started my rock band, Signal,” explains Jackson.

Michael Gregory Jackson’s Signal toured extensively up and down the East Coast between 1979 and 1983. But even with a new, harder-edged focus, he was still in tune with his more introspective side. In 1982, he recorded Cowboys, Cartoons and Assorted Candy for the German label Enja, which was originally going to be a live solo performance from the Berlin Jazz Festival in 1981 but ended up being a studio album.

This period turned out to be particularly productive for Jackson. In 1982, he collaborated with the late Walter Becker of Steely Dan. That same year,Nile Rodgers heard him at Seventh Avenue South in NYC, the Brecker Brothers’ club, and proposed getting together. This meeting resulted in Situation-X, an album Rodgers produced for Island Records in 1983, which saw Jackson on lead vocals and guitar, and featured Steve Winwood on keyboards and backing vocals for the track “No Ordinary Romance.” Jackson had shortened his stage name to simply Michael Gregory for that album, to avoid confusion with the pop phenom who shared the same name.

Michael Gregory Jackson’s Gear

A 1959 Gibson SG and a 2006 Fender Stratocaster Deluxe are Michael Gregory Jackson’s two main instruments.

Photo by Gillian Doyle

Guitars

- 1959 Gibson SG

- 2006 Fender Stratocaster Deluxe

Strings & Picks

- Ernie Ball Regular Slinky (.010–.046)

- V-Picks Medium

Amps

- Polytone Mini Brute with Eminence Texas Heat speaker

Effects

- Pigtronix Echolution

- Pigtronix Disnortion

- Modified Boss DS-1

- DigiTech Supernatural

Jackson was very prolific in his rock explorations. At times, he would write five songs a day. But past Situation-X, he couldn’t get Island Records to record and promote another rock album. Disillusioned, Jackson left the music business and took on work helping people with disabilities.

The Healing Power of the Git-Box

In 1988, Jackson returned to the music business with an RCA/BMG album called What to Where. He has since rekindled his passion for improvised music and formed Michael Gregory Jackson’s Clarity Quartet and Trio, among other pursuits.

“The concept with that particular band is to make the songs as concise and powerful as possible within four to five minutes,” Jackson explains. “You hit the ground running. Obviously, there are times when we do a long-term build up into something, but sometimes I just really enjoy getting to it right away. That’s the way playing solo is. I’m not going to generally play a piece for 10 minutes—not that I couldn’t—unless it’s really happening for me at the time. So, I try and make the pieces concise, powerful statements. And structurally, when I’m playing solo, I can move the time around. I can slow down. I can speed up. I can do all these things. ’Cause I have the freedom to do that.”

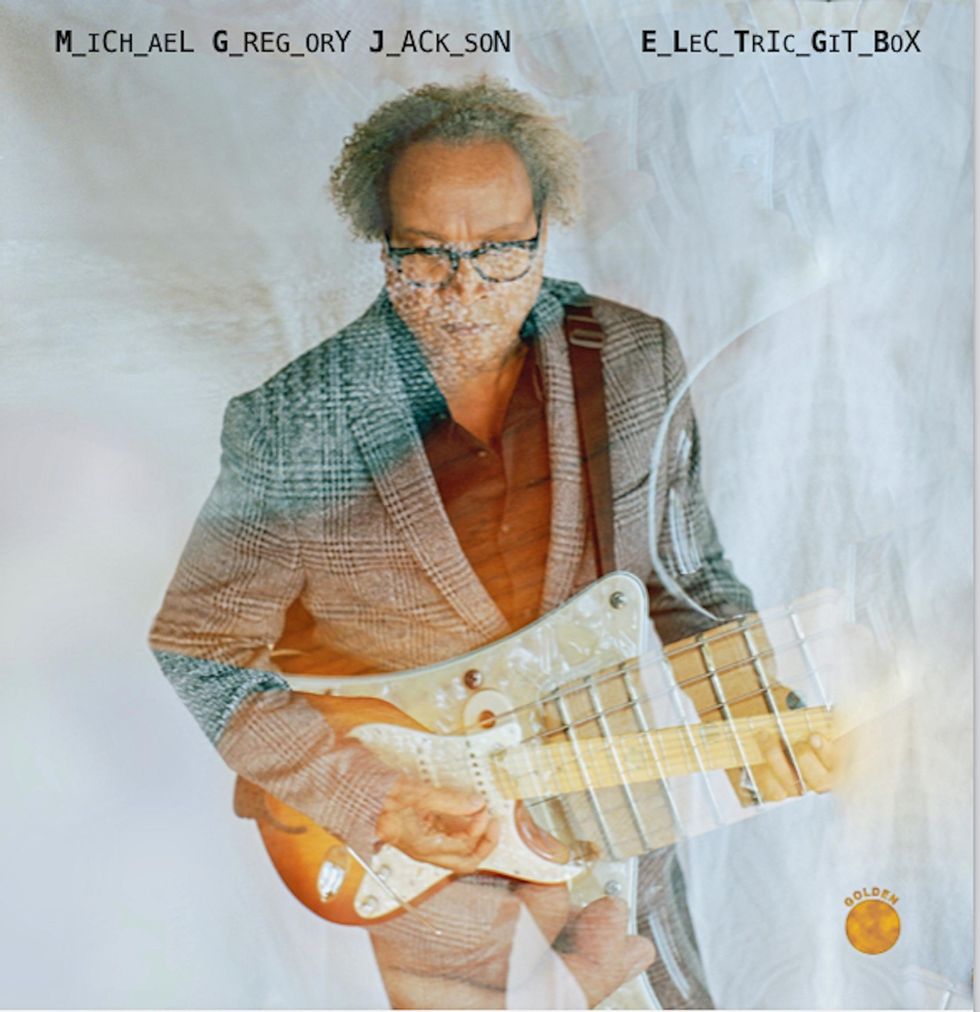

Jackson’s latest release, Electric Git Box, is an honest reflection of the strife that weighed heavily on the guitarist during the period of the recording. It was a pivotal time in his life. He had made the trip from the East Coast to the West several times a year to escape the cold and had finally decided to permanently relocate from Maine to California. After about six months staying in Airbnbs, Jackson finally found a home in Pasadena. Then, abouttwo months later, just as he was about to immerse himself in the new scene, Covid hit.

Structurally, when I’m playing solo, I can move the time around. I can slow down. I can speed up. ’Cause I have the freedom to do that.

Jackson fell into a deep funk and found it hard to reinvigorate his musical passion. “Maybe a year or more into Covid, I was not feeling that great,” recalls Jackson. “I wasn’t feeling like playing music. I was pretty stressed out by all that was happening—between Covid and the police killings of black people. You know, I was in shock. That first year, especially, was particularly rough and it was a lot to grapple with. When you have things in you and they’re intense, sometimes painful things, sometimes the urge is you don’t feel like letting them out or talking about them. I really had to go inside and do some work on feeling better about things and feeling motivated to play and make music.”

As his spirits slowly lifted, he started picking up his git boxes (Jackson’s endearing term for his guitars) again. He was asked to do some streaming concerts and that kickstarted his musical reawakening. “I decided that I would record the music with some of the edge and angst I was feeling,” says Jackson, who found the timbre of an overdriven guitar sound instrumental in expressing his inner void. “It’s not like I’m playing heavy-metal distorted guitar. It’s a kind of distortion that’s based on blues distortion. Whether it be a harmonica or a guitar, there’s a certain overdriven edge to the music, because a lot of the music is really coming from that expanse of black music. The culture is historical, and the depth of that music is incredible. For me, this was very, very personal music that I really was feeling. I was putting my Superman as opposed to my Clark Kent into it, you know?”

Electric Git Box was recorded over a three-day period and features reworked solo arrangements of Jackson’s earlier compositions, in addition to some new songs. Unlike Jackson’s previous solo guitar release, Cowboys, Cartoons and Assorted Candy, there are no overdubs or loops on Electric Git Box.

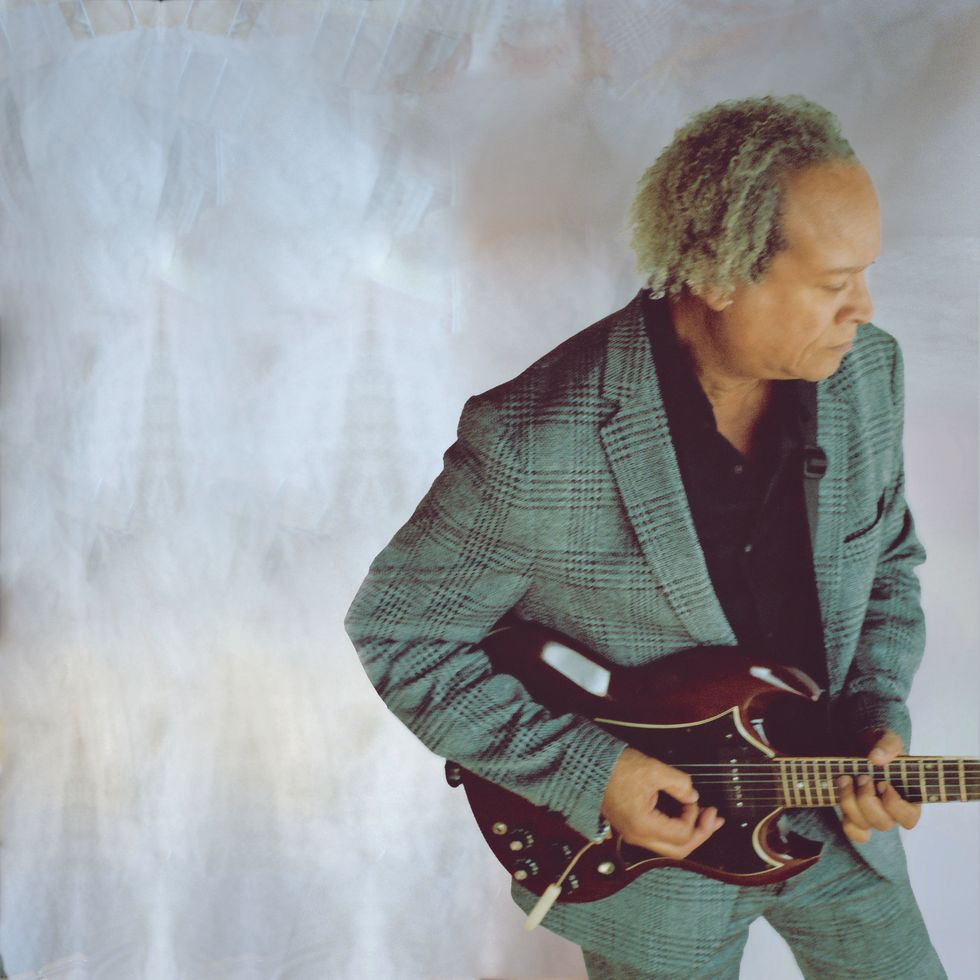

Jackson circa 1988, when he returned to the music business after a hiatus with the album What to Where.

Photo by Ebet Roberts

Other than slight delay and reverb, it’s pure-toned solo guitar, which is an extremely difficult format to succeed with. Even the late, great Jim Hall has remarked that solo guitar albums can tend to get boring fast. Electric Git Box is a compelling listen, not because of any Joe Pass-style fretboard wizardry, but because of its undeniable raw emotion and the explicit heart-on-sleeve expression of Jackson’s inner turbulence.

It is akin to a public viewing of emotional surgery, with Jackson’s git box being the only doctor capable of mending his wounds. “I was really feeling it intensely and my feelings were very, very on the surface,” he admits. “It was kind of a fight to play the music because some of it’s difficult, but luckily I’m in touch with that part of myself. I was really in the right place to convey what I was feeling. It’s real and raw, but it’s also with the intensity, fire, and emotional push that I really wasn’t going to keep bottled up. It was really liberating, and it was really saying, ‘I am free. I am powerful. I can say what I want to say.’

“Music is liberation. I am free. It’s not like I don't face what I face here in this country—systemic racism, and all of that. And you know that’s not designed to support me, exactly. So, I, we, have to find ways to live our lives and make our lives enjoyable and functional, and not just be eliminated by that, you know? ’Cause that is the goal of it—to eradicate me—which is a strange thing to live with.”

Pieces like “Karen (Sweet Angel)” and “Theme-X (For Geri Allen),” with their question-and-answer phrasing between haunting chords and despair-filled melodies, explicitly reflect Jackson’s inner turmoil. The wistful, African-influenced “Prelueoionti” sees Jackson using a fingerstyle approach to make his guitar sound like a kalimba—before using his thumb to strum a funky chordal figure with a grooving bass line embedded. “Sweet Rain Blues” opens with angry double-stops, articulated with right-hand thumb and index fingers, in a call and response with fluid pentatonic runs.

The pieces on Electric Git Box reflect a fluidity of form. “I’m not really that concerned with that aspect of the music—song form. Music is a funny thing, you know. It can be analyzed according to anybody’s system. People say the blues is a 12-bar form, and I say the blues can be any form. It was never meant to be one thing and that’s it. I mean, same thing with quote unquote jazz. No one stayed in the same place—Miles or Coltrane or anybody that you’d like never stayed in the same place. There are people that stayed in similar spots because they have a style. But you know, Miles never was interested in going back and doing Sketches of Spain. He just kept moving. And that’s the inspiration for me.”

YouTube It

Jackson’s Clarity Quartet is an outlet for him to explore new sounds in an ensemble context. “My goal for that quartet is to have them know what their voice is. Obviously, voices are always changing, but to have them know and be secure and strong enough in their voice that they could keep up and play with me,” says Jackson. “Because when I go out and play, I approach it as … I wouldn’t call it a battle, but I’m not leaving anything on the stage.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)