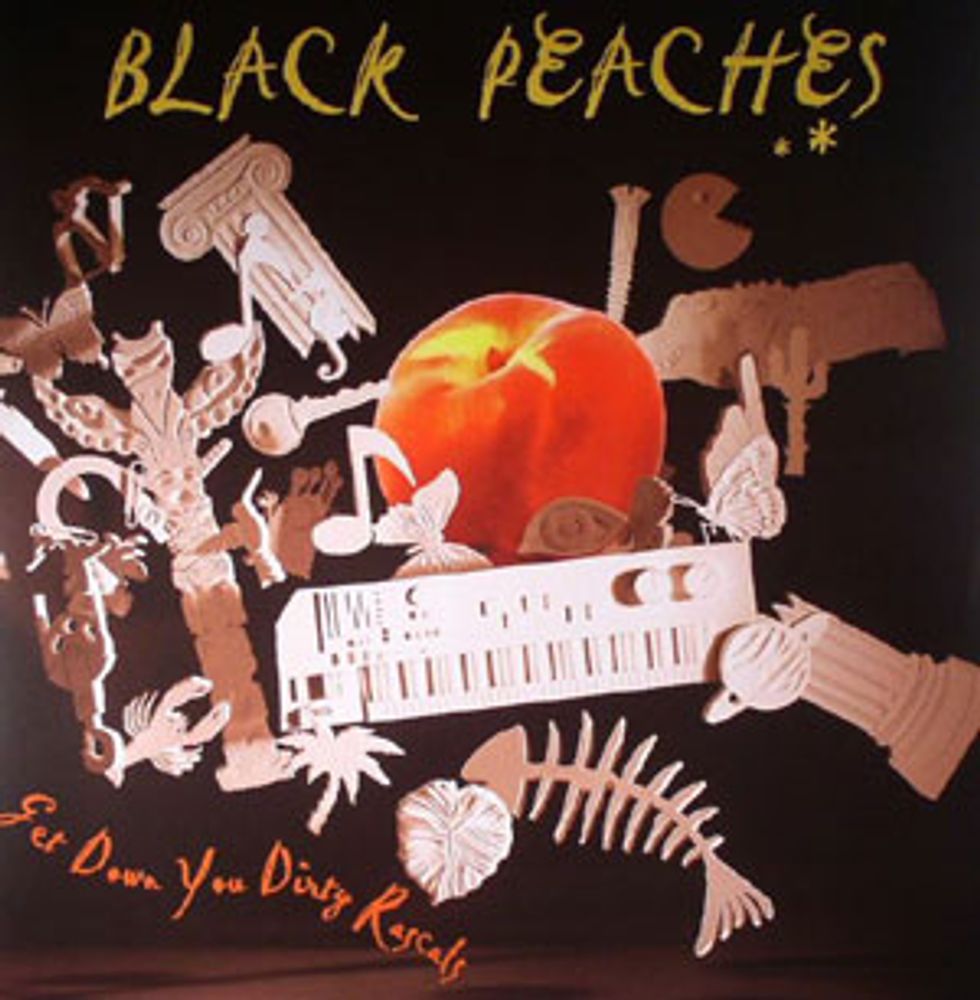

One could be forgiven for assuming the Black Peaches are an export of the Southern U.S. after a listen to the band’s debut, Get Down You Dirty Rascals. While there’s no cheesy faux drawl to singer/songwriter/guitarist Rob Smoughton’s vocal delivery, he and his five bandmates—Londoners all—have obviously done their homework when it comes to the distinctly below-the-Mason-Dixon-Line sonic patois that permeates the album, further exaggerated by the warm, compressed, and excellent ’70s-style production aesthetic in which it basks.

Get Down You Dirty Rascals is a dynamic journey through dance-worthy boogie-rock grooves that recall the hottest moments of a Little Feat set; swampy, voodoo-possessed psychedelic incantations that harken to the atmospheric wonders of Night Tripper-era Dr. John; and Latin-infused rhythmic melees with a shot of jazz—all delivered with a tandem guitar attack that is often athletic, but always smooth. And while the musicians in Black Peaches wear their influences proudly, their sound remains organic and original.

Smoughton has other gigs. He’s best known for holding down drum duties for electro-pop heavyweights Hot Chip, and he’s also a longtime hired gun for British new wave stalwarts Scritti Politti. But Black Peaches’ sonic shaman is an accomplished guitarist in his own right. He has developed a symbiotic relationship with the band’s co-guitarist and pedal-steel pilot, Adam Chetwood, who acts as his foil and sparring partner within Black Peaches’ playfully retro/nuevo mélange.

Premier Guitar spoke with Smoughton and Chetwood to discuss the recording of Get Down You Dirty Rascals (which was chiefly tracked live), their shared influences, and, of course, the gear essential to making the album.

Rob, Black Peaches’ music is a major departure from most of your resume.

Rob Smoughton: Yeah, definitely! What I’ve been involved with more over the past few years has been other people’s music, really, and this is me getting to make something that I’ve always wanted to do and be in the kind of band I’ve always wanted to be in. It doesn’t really feel so much like forging new ground as finding my way to where I should’ve always been.

How did you get into the American Southern roots music from the ’70s that the band references?

I lived in Canada for a little while, and there I met some people from the States—from Mississippi, specifically. And they led me to North Mississippi blues music. As a teenager, country-influenced rock music was kind of my big thing, like Buffalo Springfield and the West Coast stuff. When I started playing music professionally, people always needed a drummer and I like disco music and could handle it. So I wound up working with Hot Chip and playing more funk-oriented stuff, but I’ve been into country music, rock music, and jazz since my teens. I just never found much of an outlet for it.

Adam, how did you get into this style of music and playing pedal steel? I know that it’s difficult to get involved with that instrument in Europe.

Adam Chetwood: I’ve always loved anything that fuses virtuosic country players and virtuosic jazz players, so when Rob showed me the early demos of these tunes, I thought they had that flair and we clicked straight away. I got what he was going for immediately, and I immediately celebrated being involved!

As far as getting involved with pedal steel is concerned, I met a guy named Gerry Hogan, who is a British steel player with Albert Lee. Gerry has a shop in a small town called Newbury, and he sells them. I went down there and bought one, and that’s where it began.

Smoughton: We had the pedal steel on a couple of other tunes that unfortunately didn’t make it onto the final album. The only track with pedal steel featured that made it is “Double Top,” because we were keen to make it a single album.

Chetwood: Though there’s a few slide bits from you on the record, Rob.

Smoughton: One of the guitarists I really love is Clarence White [of the Byrds]. I’m influenced by his way of trying to get pedal steel sounds out of a regular electric guitar.

The chicken pickin’ on “Double Top” is fantastic. Which one of you played that part, and what gear did you use to cop the tone?

Smoughton: That’s me playing the leads, and I used Adam’s sunburst Telecaster Custom to record it. I play a lot of chicken pickin’ in open G tuning, which kind of shows the influence Little Feat had on me.

Chetwood: That guitar is a true vintage one from 1977.

YouTube It

“Suivez-Moi” from Black Peaches’ debut, Get Down You Dirty Rascals, displays leader Rob Smoughton’s way with a groove—a talent he also brings to his gigs with Hot Chip and Scritti Politti. Dig the Latin-tinged percussive intro before the song breaks into an eclectic jazzy jam driven by an acoustic rhythm guitar.

That song has some very interesting, ghostly guitar textures over the jam section. How did you make those sounds?

Chetwood: That’s the pedal steel through a Roland Space Echo. There are two tracks of pedal steel going simultaneously, and we sent them through the desk into the Roland Space Echo, which is feeding back on itself, which creates that ghostly, dreamy soundscape. That part works well more because of the textures you can get out of those particular pieces of equipment together than the parts themselves, though I think there are some beautiful little snapshots of melody in there that echo around and add a lot to that section of the song.

Adam Chetwood, slamming his 1977 Fender Telecaster Custom onstage with bassist Susumu Mukai, joined the band after hearing Smoughton’s demos of the tunes that would become Get Down You Dirty Rascals. Photo by James White

How much of the album did you track live?

Smoughton: We recorded as much as we could live and then overdubbed vocals, the occasional bits of guitar, and some extra percussion. So the core of the songs was recorded live. The songs are recorded the way we’d been playing them live, and we felt like that was the most natural way to capture them. I also like the idea of catching little bits of instruments on what isn’t necessarily the “right” mic. You try to get some isolation, but there’s bleed that catches things like guitar amps in drum mics, which we like, so we went for that.

How did you plot out the extended jam sections before hitting the studio?Smoughton: The more we played the songs together, the more we got into a natural length for things. After we realized how long a section sounded at its best without going on too long or shorting it, we developed our own little cues, which usually come from the drums, that help us live, and we used those in the studio.

The weaving guitar parts on “A Fire & Water Sign” are exceptionally cool. How did you both develop those parts, and who played the solo? The tone is really killer.

Chetwood: The main, Keith Richards-style playing evolved through our rehearsal process and trying really hard to deliberately get that weaving thing going, and it was a natural fit for that song. The solo was me and I used a Roland JC-50 combo with the chorus on, and the guitar I used was a Les Paul Custom from 1981. We did a few takes of the solo, and it was an overdub that Rob comped under. It’s pretty cool that both the guitar and amp used were probably made around the same time.

Smoughton: That weaving thing originated with much more playing going on. We focused on working out more space for each other’s little guitar parts. We had an RCA ribbon mic in the room, and when it came to mixing the track, the room mic was quite high in the mix and a lot of the room sound was captured on that solo, which I think really helped to get that interesting, lively sound you hear.

Rob Smoughton’s Gear

Guitars2014 Epiphone Wildkat with P-90s

1982 Hohner Professional SE 400 with Kent Armstrong Humbuckers

2009 Vintage VSA535 12-String

Sigma OOOR-42 acoustic

Amps

Vox AC30

Fender Princeton

Vox AD50VT

Effects

Mooer Yellow Comp

Mooer Acoustikar acoustic guitar simulator

Mooer Ninety Orange phaser

Mooer Pure Boost

Mooer Rumble Drive

Z.VEX Fuzz Factory kit-built clone

Jim Dunlop Cry Baby wah

Boss DD-3 Digital Delay

Roland RE-201 Space Echo

AMS DMX 15-80S Broadcast Delay

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball Hybrid Slinkys on the Hohner

D’Addario EXL110 Nickel Wound, Regular Lights (.010–.046) on the Epiphone and Vintage

Martin M-540 (.012–.054) Phosphor Bronze Lights on the Sigma

Dunlop 1.0 mm Big Stubbys (electric)

Dunlop 0.5 mm (acoustic and 12-string)

Adam Chetwood’s Gear

Guitars1977 Fender Custom Telecaster with Mastery M3 Bridge

1981 Gibson Les Paul Custom with a Bigsby

’90s Gibson Les Paul Standard with a Bigsby and Bare Knuckle Mississippi Queen P-90s

’80s Greco Spacey Sound with Bare Knuckle Apache single-coils

MJT Nashville T-style with Florance Voodoo pickups (ST60 middle, TE59s bridge and neck), Callaham and Kluson hardware

Carter Starter 10-string pedal steel

Amps

Matchless DC-30

Torres-modded Fender Bassman 4x10

Roland JC-50

Effects

Boss TU-3 tuner

JHS Mini Foot Fuzz

Strymon OB.1 Optical Compressor & Clean Boost

Keeley-modified ProCo RAT

JHS-modded Electro-Harmonix Soul Food overdrive

Green Ringer ring modulator clone by Jake Feinberg of Goldsoundz Electronics

Boo Instruments CE-2 chorus

JHS Panther Cub analog delay

Boss DD-2 Digital Delay

Mooer Trelicopter tremolo

TC Electronic Hall of Fame Mini Reverb (loaded with Albert Lee's toneprint)

Roger Mayer Voodoo Vibe

JHS A/B (to switch channels on Matchless)

Fender ’63 Tube Reverb

Radial J48 D.I.

Ernie Ball volume pedal (for pedal steel)

Peterson StroboFlip Tuner (for pedal steel)

Strings and Picks

D’Addario NYXL (.011–.049)

Dunlop Graphite Jazz 3

Jeffran College thumb and finger picks

Dunlop 921 Tonebar

The album really captures the charm and very specific compression of the records from the periods and genres you’re referencing, but it’s a higher-fidelity version that still captures the personality of that music.

Smoughton: We definitely had a sound we wanted to go for, and that was us playing live with some bleed. But we wanted to use the nicest equipment we could get our hands on. So we went to a nice studio in London—Tin Room Studios—that had a collection of great vintage mics and a nice board, and enough top-notch outboard gear to get that warmth and compression. But it was mixed digitally, so that might lend itself to the higher fidelity, and we weren’t limited to how much we could fit on tape or anything. The point was to create something with that ’70s warmth, but to layer the way you can with modern technology and use enough room and ambient mics to capture the energy of a band actually playing.

Rob, how much responsibility did you place on yourself to say something fresh within this style, which claims so many iconic bands?

Smoughton: When you’re talking about bands like Little Feat or the Southern rock that informs our sound, that’s just one part of what we do. We take a lot of influence from Latin rhythms and Brazilian percussion, and we take that country-rock-boogie thing down a very different road with that Latin influence. And even with some of the jazzier sounds we use. We weren’t trying to remake an era of music. We were trying to draw from influences that happened to mainly come from the ’70s. However, we wanted to create something that sounded like our band, and that’s freeing because you don’t have to sort of tick off all the boxes of remaking a classic sound. You can pull from so many different things.

Also, from a songwriting perspective, when I first started sending things to the rest of the band, they were half-finished songs and simple ideas. They only came into the proper light when the rest of us played them together. Everyone’s bringing something in the way they play and with their individual musical personalities. It’s not too anachronistic. It’s not too much of an homage. We just wear our influences plainly and visibly.

The fiery guitar on “Below the Waves” is some of my favorite playing on the album. Who played it and what gear was used?

Smoughton: That’s actually both of us! That’s a real mix. I think we swap off for a bit with a call and response, and then it’s both of us at the end. We tracked it together live, rather than overdubbing, and there’s a little bit of bleed in there between the amps. I believe I used my old Hohner SE 400, which is like a Gibson hollowbody, but made in Germany around 1982. It has two humbuckers, and I was playing that guitar through a Vox AC30 that belonged to the studio.

Chetwood: I was using a 4x10 Fender Bassman that was modified by a company called Torres Engineering, so it was hopped-up a bit and it did sound particularly good.

There seems to be a really great synergy between the two of you as guitarists. Was that naturally there? What is it about your styles that allows you to work so well together?

Smoughton: Adam’s more versed in jazz guitar than I am, and my parts require more sketching-out beforehand. Adam is a bit more off-the-cuff and a better improviser, and has a more explosive style than mine, which seems a little restrained by comparison.

Chetwood: We definitely hit it off immediately with where the guitar fits into the sound of this band, and we share a lot of common ground with our influences. I think since the band’s evolved, we’ve picked up little bits of each other’s styles. I’ve started creatively playing bits that wouldn’t have come to me had I not been working with Rob. We’re both big Larry Carlton fans!

Smoughton: Especially his Steely Dan work. And since Adam and I have been playing together, we’ve gotten really good at harmonizing, and we’ve worked out how to play leads together in that way. There’s an intuition that’s come around from us playing together now for a couple of years that we’ve carved out. It’s something that came to us organically.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)