The title of the John Butler Trio’s seventh studio album, Home, is a bit ironic. Admittedly, it comes on the heels of bandleader John Butler spending more time with his family during the four-year break since Flesh & Blood, and the title track is about the guitarist missing his domestic life while on the road. But the recording itself, both in style and in its production process, marks a noteworthy departure from the Australian trio’s traditional method.

While typically the band has recorded albums with plenty of group input during its 20-year history, on Home, Butler ended up becoming more personally involved in production, bringing his interests in electronic music and hip-hop into the mix, and really driving the recording sessions and musical approach. As a result, the project breathes with modern, digital colors that bond with a wellspring of his signature folk-blues-rock “acoustica.”

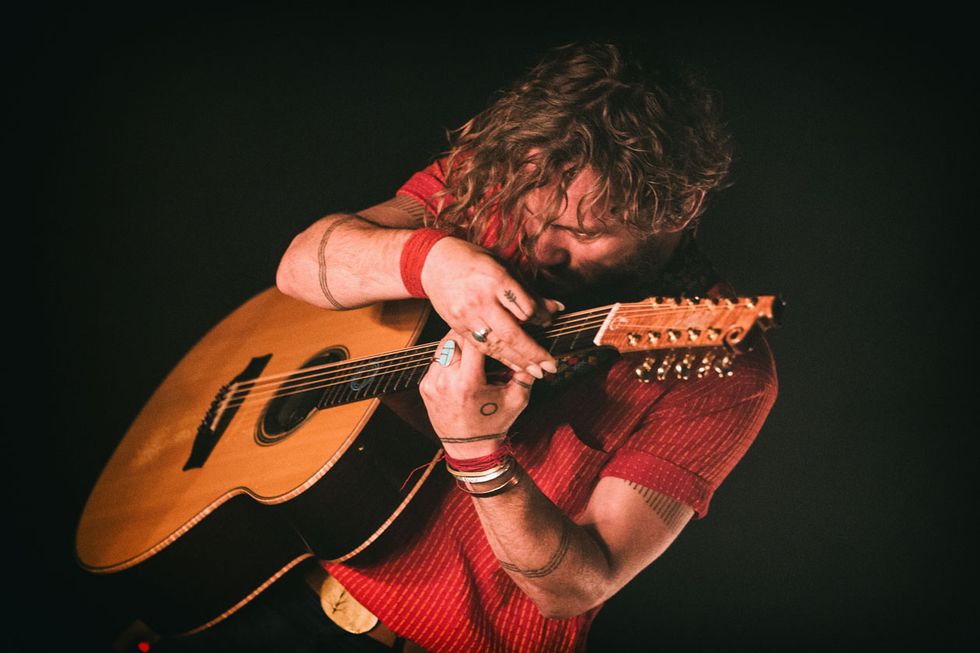

But throughout the album’s dozen tracks, it’s clear that Butler remains a stunning instrumentalist. These days he prefers to perform on his Australian-made custom 11-string Maton acoustic guitar (strung like a 12-string, but without the octave G), which he picks just with his fingernails.

It has been four years between albums. What went on during that time?

I always have three years in between each album to tour and promote that album. Then I took a year off, because we relocated our home three hours south. We’d been touring incessantly for a decade, and I just thought it would be nice to take a bit of time, make a chicken shed, make a workshop, and make some friends [laughs], you know? Then there’s a bit more touring and recording. It was very full.

How does the time you spend onstage shape your music?

Songs, when I start to write them, are still in utero in a lot of ways. They’re kind of born once they get recorded and are on an album—they’re infants. Then you take them on the road for three years and they grow. I think everything wants to change, and the live format is such a perfect garden bed for things to grow. You see what works every night, see what doesn’t, see what happy accidents happen. Ten years later, the song sounds like the same song, but more grown up.

How do you nurture your songs in the studio?

I just work for the song. The song is boss and I’m the employee. The more I can surrender myself to the song in the recording process, the better it can be. Some songs I think should have loads of guitar on them, and at the end of the day they turn out with no guitar on them because that’s what the song wanted. I just keep on trying to stay open. Sometimes that’s musically open, or production-wise open. Sometimes it means emotionally open—going on a huge existential kind of journey to realize the song.

Not all bands are great live. What appeals to you about the live performance dynamic?

It’s always kind of been that way for me. I started my career busking on the streets, and from there that’s how I learned, how I shared my music. It’s where my independent music business started. I was advertising, producing, managing, recording.

It’s always been out in public, I guess.I’ll have a career in 10 years’ time because of the relationships I make now onstage. And that’s a really beautiful thing. It’s great having big albums. I’d always wish to have a nice big album, but big albums come and go and so do their fans. Relationships that you make onstage through a live experience are awesome. And then if you have a great album on top of that, that’s the perfect scenario. That’s what I’m always aiming for.

What makes a great live show, for you?

Some bands want to be clapped for, and some audiences want to be played to. I want to do something with the audience. It’s very symbiotic. When they give and then we give, it just gets bigger and bigger and it builds and it builds and that’s the magic that keeps me addicted. I am totally jonesing on that experience. It doesn’t happen every time, and that’s why I’m an addict—because I’m searching for my next magical fix.

TIDBIT: On Home, his trio’s latest album, John Butler took a less democratic role and developed the core rhythmic approach to many of the album’s songs using the beat-making abilities of GarageBand.

What is your go-to guitar?

A Maton jumbo 11-string, which is basically a 12-string without the high G. That’s my main axe.

What gear are you particularly fond of?

I use a Midas 2-channel strip off a mixing desk. Another bit of gear I use is a Seymour Duncan Mag Mic magnetic pickup. I also use my Maton AP5 pickup, which is based off technology on a Takamine. And then I put them into each channel of the Midas XL42 mixer, which acts as my really high-end blender. That’s my main acoustic sound—a combination of magnetic and piezo technology. Then I go through a whole bunch of effects anybody can go through. Once I go into my DI, I take the through from my magnetic side and plug that into an Ibanez Tube Screamer and into a Marshall JMP Super Lead 100 watt amp. But really importantly, that’s going through a volume pedal, so it’s not always on. I’m able to have this acoustic sound, and then with the volume pedal bring in this completely overdriven dirty sound on the top of it, which allows me to do all kinds of rootsy acoustica and bring in all the mayhemic rock stuff that I love as well.

Although John Butler plays conventional 6- and 12-string guitars, his current favorite instrument is a custom Maton 11-string that’s tuned like a 12-string but omits the octave G. Photo by Helen Millasson

What other effects do you use?

I use an octa-vibe, a [DigiTech] Whammy, a [Crybaby 95Q] wah, a [Boss PH-2] phaser, two types of delays—got this really cool delay called a Kilobyte, which I really love … octave pedal, reverbs, [Akai] Head Rush. That’s about it. I have a [GigRig Loopy 2] loop switcher for my bridge pickup, so I can do kind of percussive loops with the Head Rush.

How often do you use looping?

I use it more solo. I loop a lot of EBows when I’m trying to create this real ambient kind of pad. I’ll use about six tracks of EBow and my Head Rush. It’s not very traditional. It’s like all worlds in one.

Who influences your guitar playing?

There are the prophets that kind of are cornerstones, but I don’t try to sound like them. To me, they are the epitome of letting the spirit come out of the instrument. Hendrix is one of the greatest, and then there’s people like Debashish Bhattacharya, the amazing Hindustani lap-slide guitarist, and Jeff Lang, who’s an amazing fingerstyle singer-songwriter guitarist who blew my mind and introduced me to the acoustic amplified world. Then there’s Celtic fiddle, Celtic mandolin, jigs and reels, and bluegrass fiddle, mandolin, and banjo. I love all that fingerpicking stuff, and I like playing it on a 12-string, with a high G off it, through a Marshall. That’s kind of how I interpret all those influences.

How did you get into music?

Basically, just through my parents and my brother. I was exposed to all their music: Fleetwood Mac, Elton John, Frank Sinatra, AC/DC, Black Sabbath, Iron Maiden, Jane’s Addiction. With Jane’s Addiction and my first Violent Femmes album, I was like, “Okay, I found my people.” Being a kid growing up in the ’90s, one of the greatest decades for music in the last 50 years or so, there was a lot to pull from. But that was just getting into music. I got into playing guitar when I was 13 and broke my arm a couple times—once from skateboarding, and then the other time jumping off a trampoline. And then I was given my grandfather’s Dobro when I was 16. I didn’t know what to do with that for about five years, actually. And when I turned 21, as just a hobby guitarist, I discovered open tuning and got completely obsessed. Obsessed, like OCD obsessed. That changed everything—made the Dobro totally make sense. I found my voice on guitar. I was going to university for fine arts with the idea of becoming an art teacher, and I quit university and started busking on the streets. At the age of 21, I decided I wanted to do music. I didn’t grow up wanting to be a rock star by any means. I’ve just kind of been jonesing on that trail ever since, really.

How did you get into playing so many different stringed instruments?

Through open tuning. Because the minute you can play in open G tuning on the guitar, the banjo makes perfect sense. I’m not saying you’ll be a great banjo player.

Guitars

Maton Custom Jumbo 11-string (2018) with Maton AP5 Pro and Seymour Duncan Mag Mic pickups

Maton Custom Jumbo 6-string (SRS70J style) with Maton AP5 Original and Seymour Duncan Mag Mic pickups

American Special Telecaster with Texas Special single-coil pickups

Harmony Meteor H70 with DeArmond gold-foil pickups

Bacon 5-string banjo

Lanikai baritone ukulele with Shadow preamp and pickup

Amps

Marshall Super Lead MkII

Marshall JCM800

Fender Hot Rod DeVille 212

Effects

Lehle Little Dual amp switcher

RJM Mini Effect Gizmo switcher

Dunlop Cry Baby 95Q Wah

DigiTech Whammy (fifth generation)

Electro-Harmonix Micro POG

Boss PH-2 Super Phaser

EarthQuaker Devices The Depths

Seymour Duncan Pickup Booster

Caroline Guitar Company Kilobyte

Strymon TimeLine

Akai Head Rush

TC Electronic Hall of Fame

J. Rockett Audio Archer

Nessfield Bluezer

Maxon OD-9

DigiTech JamMan Solo

Mr. Black Eterna

Korg XVP-20 Volume/Expression Pedal

RJM Mastermind GT/22 MIDI controller

Midas XL42 preamp

JHS Buffer Splitters

RJM Y-Not

GigRig Loopy 2

Strings and Picks

D’Addario EXP38 (.010–.047) 11-string acoustic

D’Addario EXP26 (.011–.052) 6-string acoustic

D’Addario NYXL1149 (.011–.049) Telecaster

D’Addario NYXL1356 (.013–.056) Harmony

D’Addario EJ61 (.010–.023) banjo

Custom D’Addario nylon uke (.028, .034, .024, .028)

You expanded your sound a bit on this album, moving away from the traditional roots-rock feel. How did that come about?

I got really into GarageBand, and, for the first time as a songwriter, I was able to elaborate on my ideas in real time, as opposed to waiting two weeks to get together with the band and have them try to interpret what I meant to make something happen. One of my favorite albums is Missy Elliot’s Under Construction, which is full of programmed beats and synthesizers. And I love Beyoncé, Adele, Skrillex. I had these drum machines all of a sudden and all these instruments on one little iPad, which made producing the music so much more immediate. I was able to go into this nice little sonic wonderland and add a whole bunch of extra colors to my palette, which was super fun for me, and then I took that all the way to the album. It was a real solo production in a lot of ways. It wasn’t so much trio-based at all. It was more about what I’d done in pre-production, and how to bring that vision to life in its most pristine, undistracted way.

What was it like creating this album?

Ah, it was a complete journey! I went from thinking I was going to go into my studio with my trio and bring these songs to life to ending up being on the other side of the country by myself in a studio with a producer. I came to terms with the fact I was dealing with anxiety, something that now I look back and realize I’ve been dealing with on and off for probably a decade. But it got pretty acute when I was trying to work out what I was attempting to do with this music. It was pretty intense. It felt like I was going about it all wrong. But that was the journey of letting go of all that stuff and being a bit human. Every album has been that way, which is always a bit frightening. The album before was really easy to make—it was really fun, and I’d never experienced that. But this album was soul-searching, man. An odyssey, a rite of passage.

What song on the record has the most personal or interesting story behind it?

They’re all kind of different little beasts. “Coffee, Methadone & Cigarettes” is a song about my grandfather passing away in a bushfire in Western Australia in 1958, and the effects that it had on my dad and my whole family. Then there’s “Home,” which has no guitar on it and wasn’t going to be on the album. I just wrote that song on GarageBand on my iPhone—all the beats and everything—and then I finished the lyrics with some other songwriters. Guitar-wise, “Faith” was probably one of my most favorite guitar moments. At the very end of the song, I had this solo worked out—this double-thumbing, blues country-picking thing—and the song just kept saying, “Oh shut up! Boring!” I was like, “Really? I thought it was really good. I’ve been practicing this solo for, like, two years now!” [Laughs.] So I ended up coming up with this hammer-on, hammer-off psychedelic delay flanger thing that became a complete moment on the album, which was something I could never have foreseen. The song is so metaphysical, and at the very end when all the lyrics have done their job and they hand the baton over to the guitar, the guitar goes quantum. I tried the solo about 20 times and then it turned out to be whatever thing it is. I don’t understand it, but it’s cool.

Is there a way for you to gauge what’s going to work in a song?

No, not really. It’s not necessarily about being in tune or in time, or being the next Leonard Cohen or the next Hendrix. It’s just—it’s gotta get out of your head and into your heart. That’s easier said than done, of course. That’s what I love about music, and the recording process forces me there. And it’s not always easy and it’s not always painless. A lot of times it’s completely tumultuous. But, yeah, it’s a journey, you know?

Fingerpicking his Maton 11-string custom acoustic at Studio Pigalle in Paris for a Rolling Stone session, John Butler leads his trio in “Just Call,” off the new Home album. Note the simple slide flourish he uses to close the song with a fresh sonic color.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)