Some of the most interesting developments in the span of rock history have come about accidentally, through abused or malfunctioning gear. In the late 1950s, for instance, the guitarist Link Wray poked holes in his speakers, for a gnarly, distorted tone, while the earliest use of fuzz arguably came from a messed-up preamplifier on the studio session for the 1961 Marty Robbins song “Don’t Worry.”

Peter Hook, who for decades has had one of the most identifiable bass-guitar sounds in rock, owes his instrumental voice to a similar gear scenario. At the onset of his career, in the late 1970s, a crappy amplifier forced him to take a decidedly unconventional approach to the instrument.

Hook is a founding member of Joy Division, the English post-punk band that also included vocalist Ian Curtis, guitarist Bernard Sumner, and drummer Stephen Morris. The group only recorded two full-length albums—Unknown Pleasures (1979) and Closer (1980)—before Curtis was found dead from suicide in 1980. But decades later, Joy Division’s slim catalog remains hugely influential, in no small part owing to Hook’s high, singing bass lines on songs like “Love Will Tear Us Apart” and “Transmission.”

After Curtis’ death, Joy Division carried on as New Order. Dance and electronic sounds were in vogue in the 1980s, and in incorporating these strains, the group began to rely more extensively on synths and drum machines. But on songs like “Blue Monday” and “Bizarre Love Triangle,” Hook remained committed to his melodic role on the bass.

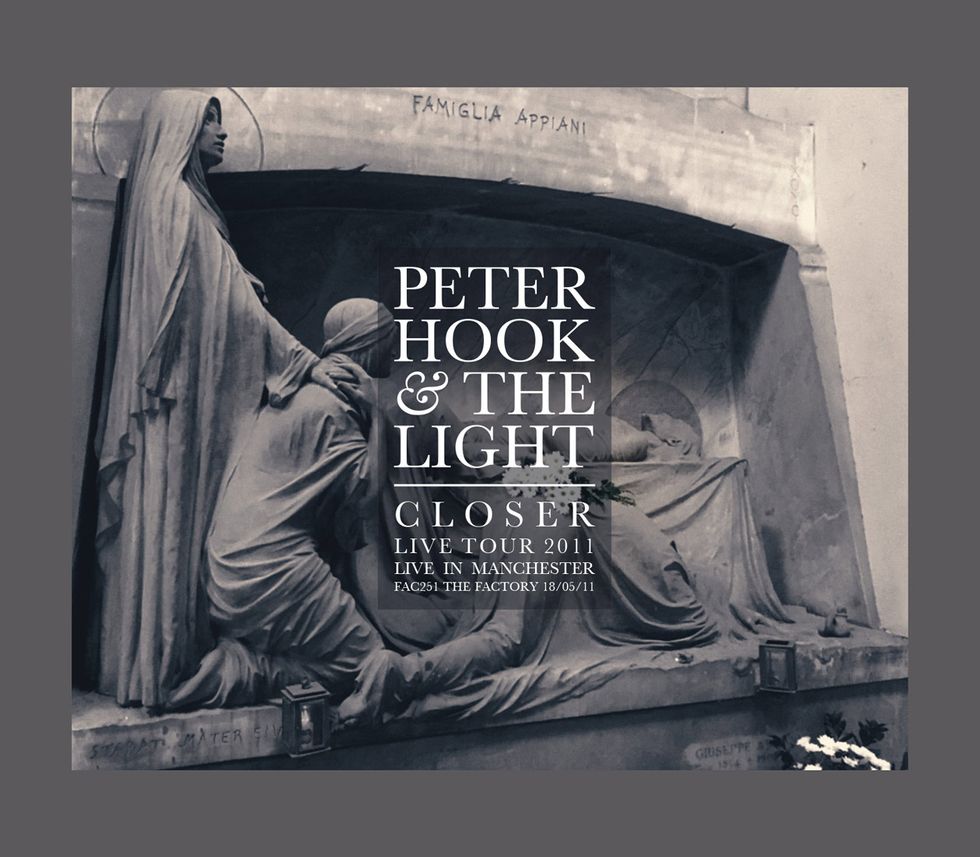

New Order has been known to disband on occasion, and after a particularly acrimonious split in 2007, the group came back together—without Hook. Since then Hook has gotten sweet revenge by penning a tell-all book, Unknown Pleasures: Inside Joy Division,and by performing Joy Division and New Order albums, complete and in sequence, with his own band, the Light, in concert.

Hook and his group’s performances of Joy Division’s two albums and New Order’s Movement and Power, Corruption, & Lies were recently released as CDs and downloads, as well as limited-edition colored vinyl. The albums find Hook in top form as he revisits these post-punk classics with his band, which includes his son, Jack Bates, on bass, Andy Poole on keyboards, and Paul Kehoe on drums.

Calling from a hotel in Denmark, Hook reminisced about that inferior amp, the working processes of Joy Division and New Order, and how these bands’ methods inspired maximum creativity.

You have quite the idiosyncratic voice on the instrument. Can you talk about how you developed that sound?

It was quite simple. It came out of necessity. My first amplifier I ever bought was called a Sound City 120—a terrible amplifier that at $150 was quite expensive at the time. And my speaker was a single 18"—I don’t know what make it was; it didn’t have any labels on it—that cost me $15. My first guitar was an Eko copy of a Gibson SG bass, which cost $50. And basically, the rig sounded awful.

As a bass player you’re presumed to only play low notes and follow the guitar chords and things like that, which didn’t appeal to me. It didn’t help that the sound of the low notes was absolutely awful—indiscernible. So, I started playing up the neck and developed that penchant, shall we say, for high melodies in Joy Division. Our singer—Ian Curtis, God rest his soul—loved it and encouraged me to do it more and more. And as my mother once said, it’s a debate whether it was through talent or luck that I sort of developed my own style. But whatever it was, it worked in Joy Division. And obviously, those high bass melodies, counterpoints to the vocals, also worked in the group’s next incarnation as New Order. My approach kind of became the mark of the group and I’ve been able to keep it and still utilize it now.

Live, Hook plays entire albums by Joy Division and New Order with his band the Light, and releases the shows on record. “I’m working through the whole of Joy Division and New Order’s back catalog, from start to finish, hopefully before I die,” he says.

Did you miss playing and hearing those low frequencies at first?

No. I think the most disgusting thing I ever heard in my life was when our guitarist said to me, “Can’t you just follow the guitar?’ and I said, “No I can’t, actually.” That was our first fallout. But yeah, I mean, I’ve never been very good at being told what to do. I wasn’t a musician until I was 20. I saw the Sex Pistols play in Manchester, and though I didn’t yet have a musical instrument, I became a musician right after the gig. So, I started late, and at the bottom, and I’ve never been what you would describe as a normal bass player. I prefer to strike my own ground, shall we say.

How, if at all, has your approach to the bass guitar evolved over the years?

It hasn’t really. I do feel guilty about it, time to time—especially when popping came in vogue and a very good friend of mine, Donald Johnson, tried to teach me to pop. After a couple of lessons, he said to me, “Okay, why don’t you stick to what you’re good at?” I took that advice to heart and have stuck to what I’m good at.

You know, in the ’90s people used to say to me, “As soon as a New Order record comes on, I can always tell by the sound of your bass that it’s New Order.” At the time, I didn’t take that as a compliment, but now, at the ripe old age of 61, I think it’s a great thing. And to be asked to play on peoples’ records as I am, to lend that signature sound as a nod to Joy Division and New Order, is a great honor. Especially if I get paid for it, which most of the time I don’t.

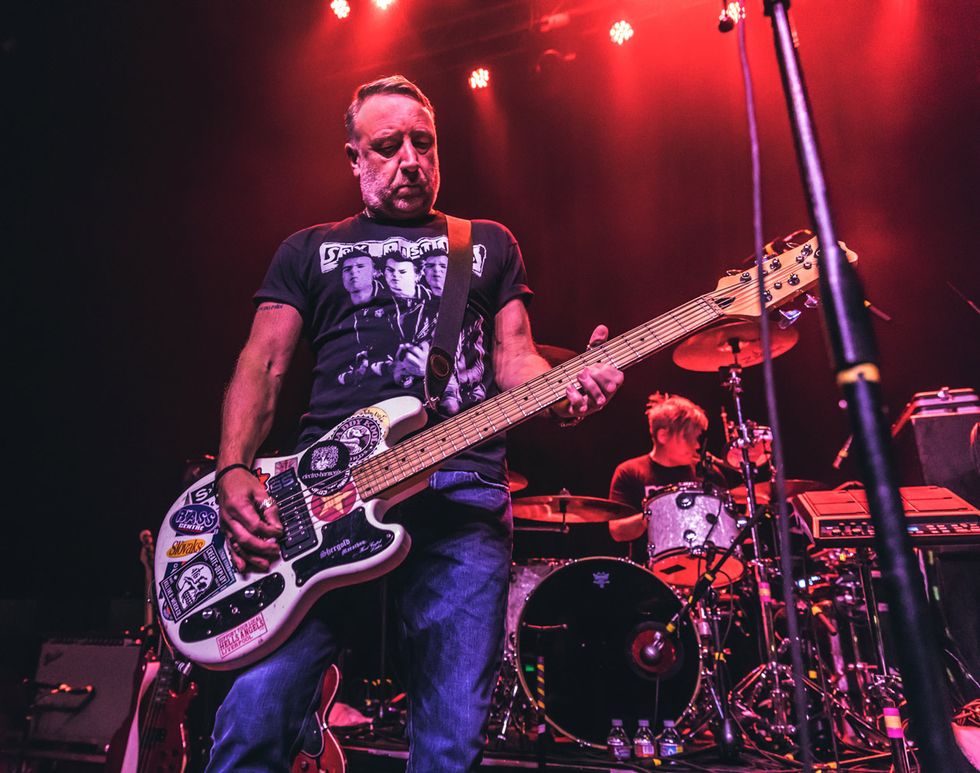

Hook sometimes relies on this Shergold Marathon 6-string, which he punked-up with a slew of stickers. The instrument is inspired by the Fender Bass VI and has a 30-inch scale length. Photo by Nikolai Puc

What were the working processes of Joy Division and New Order like, in terms of songwriting and recording?

We always wrote the same way. It was very equal in Joy Division. Each member wrote his own parts. It’d be very rare for any member to be encouraged, shall we say, or bullied into not writing his own part, so it was very easy, and always from jamming together. In fact, for the first year of Joy Division, we didn’t have a tape recorder. We couldn’t afford one. The only time the music existed was when the four of us got together to play, which is quite an insane thought in this day and age of ease with which everyone can record everything and change it to their hearts’ content.

The wonderful thing about recording was how immediate the process was. You couldn’t change it much because of the analog format. You had to go along with it and work with it, and it made for some wonderful and wacky mistakes. It kept you very buoyant, very busy, and engaged. The lead singer wasn’t disappearing with the laptop for three months and bringing the music back with it sounding completely different.

It was a completely different way of writing and recording compared to how you do it nowadays. And I don’t think most music is better for it. Today you pore over the music for hours, weeks, years. And then somebody else pores over it. It’s a very strange process. When I was writing my book—which was the history of the band from 1980 to 2011—I was aware that the monumental change in recording came with the advent of computers like the Apple SE.

In a nutshell, what do you think went wrong with New Order?

You have to be careful with the way that you act in a group. You have to work on making sure all the members are included. One of the reasons New Order split up was because the lead singer decided he was in charge and started acting that way, and I just thought, “This isn’t a group anymore. This is like a dictatorship, and it’s a terrible place to be.” People shouldn’t do it to other people and neglect to see that a song always is, in my opinion, never more important than the band. To me the band is the most important thing in the world.

That’s a really good point. What do you think has been lost in music as a result of today’s recording technology?

Well, there’s the happy accidents, for a start. If you listen to a song like “Blue Monday,” which still is the biggest selling 12-inch in the world, it’s littered with mistakes. [One section might be] six bars [long], you know, 12, 10 bars [when repeated]. Sometimes even five bars or three-bar breaks and stuff. Because when you were laying it down, you didn’t count the bars properly, so you had a lot of weird and wacky timing, and odd little bits, which you don’t do now because now you just correct it on the computer.

So you’d lose to that sort of intangible uniqueness: those happy accidents that happened in music. You’d have to work around it because you couldn’t afford not to, or didn’t have the technology to change the backing track.

Peter Hook’s Gear

Basses/GuitarsCustom Chris Eccleshall bass

Yamaha BB1200S

Shergold Marathon 6-string

Amps

Yamaha BE-200

BS-100 cabinet with 2x15 JBL 4560s

Effects

Electro-Harmonix Stereo Clone Theory chorus

Joyo JF-08 Digital Delay

Strings and Picks

Elites Strings Stadium Series Standard Gauge IV (.045–.105)

Dunlop 1.0 mm nylon picks

And as I’ve transcribed all the old Joy Division and New Order material, I’ve realized those happy accidents actually gave it a unique feel. In music today, if you’re computer-savvy you have all the choice, all the time in the world to go, “Oh, that’s a mistake, let’s take it out.” I think because of that you tend to lose a lot of the immediacy, a lot of the wonderful and unexpected moments. And I listen to a lot of material now and think, “Oh, man. It’s just programed within an inch of its life.”

There’s a huge difference between [an analog] 24-track recording and a digital recording, you know. And you miss it. I think the thing about the resurgence of vinyl is ... I think the human condition responds better to a little bit of softness and a little bit of warmth than it does to the cold sort of starkness of computing digital treatment.

Also, I don’t want to start harping on about how the internet has certainly taken a lot of my earnings from me in the same way the journalists suffer—being appropriated without your permission. The internet really hampers our earning potential.

But as with anything, there’s good points and bad points. The thing about it is digital recording is a lot cheaper than analog recording used to be—and a lot easier because anybody can do it in the bedroom. It’s literally the computer equivalent of the acid-house revolution that happened around 1986, ’87. The advent of the new cheap digital machinery would’ve helped a lot more people become musicians if it had been around in the early to mid ’80s. Electronic musicianship was the pursuit of the middle or upper-middle class only. You had to have very rich parents or a very good job to participate.

What do you think are some of the advantages and disadvantages of how the cheapness of gear has made it more accessible?

The advantage has to be the ease [of operation] and the ease of access for anybody. The disadvantage is you do get a lot of bad material. We all know beauty is in the eye of the beholder, but in the same way that you get great chefs and bad chefs, it’s the same with music.

But songwriting is a very underestimated art. A lot of artists that premiere today are propped up by a stable of good songwriters, you know. It’s become quite the norm for singers not to write their own material. I’m very lucky to be a songwriter, and I think it’s something you can’t teach. It’s still a very intangible art, which should be celebrated more.

Peter Hook’s custom Chris Eccleshall bass weds the scale and feel of Hook’s 1981 Yamaha BB1200S with the semi-hollowbody design of a Gibson EB-2.

Which bass guitar are you playing these days?

I’ve used the same guitar, a custom-built Chris Eccleshall, since the mid 1980s, so it’s practically a vintage guitar now. It’s a copy of my 1981 Yamaha BB1200S. And it’s also sort of bastardized into a Gibson EB-2, so it has all the attributes of the Yamaha with the body shape of the Gibson. Also, because it’s semi-acoustic, it allows me to use controlled feedback, which is quite nice.

My dream guitar was a Gibson EB-2. Unfortunately, because they’re medium scale only, they don’t hold the tuning well enough for my purposes. So, the thing is, I wanted to combine all the great attributes of the Yamaha BB1200S—the EQ and the neck, which is straight-through—but have the advantage of the hollowbody. It was just a matter of being able to afford to have my two dream guitars amalgamated into one.

I should add that I’m very lucky to have been nominated for a signature model this year. Yamaha is building me some new BB1200Ss, which is a great honor.

How did the new live album recordings come about?

The live album project was quite a gift, actually. I was being courted on behalf of Joy Division by a merchandiser. And he didn’t get Joy Division, but he came to a gig and said to me, “Ah, your band plays really well. You should do a live album on my label.”

I liked this guy—he’s Steve Beatty and works at Plastic Head, which is a big merch company in England. And I said, “Well, yeah, our keyboard player has been recording loads and loads of gigs—some 24-track, actually.” So, we were doing it for fun, which I think was a nice thing because it means that none of the gigs have the pressure and feel of being recorded for a special occasion. They’re quite relaxed.

And we were able to choose from a hell of a lot of recordings. My gimmick, if you like, is that I’m working through the whole of Joy Division and New Order’s back catalog, from start to finish, hopefully before I die. The idea was to chronicle each LP with a release, and we’re up to the eighth and ninth LPs in the series.

You play with your son, Jack Bates, in the Light.

I’m very lucky in that he plays bass with me. In the group, he’s very good at emulating me, and that makes me very happy. We work quite well together. But I’m also glad he’s been able to leverage this work into getting a gig with the Smashing Pumpkins, where he plays in a completely different style than the one he uses with me. I couldn’t do that job. It just shows how much more versatile my son is than I am.

What’s it been like for you to revisit these Joy Division and New Order songs?

It’s a bit different for me because I’m singing, whereas before I was just the bass player. I’ve had to look into the singer’s psyche and step into the singer’s footsteps. In Joy Division there was a lot of expectation, and Ian Curtis’ shoes were very big ones to fill. In New Order, Bernard’s shoes were a little bit snugger, shall we say. And because we’d written the vocals and the melodies together in New Order, it was easier to feel part of that. I gained an insight into the lyrics and the lead singer’s job.

Has getting into the lyrics and the singer’s headspace changed the way you approach the bass lines?

It hopefully hasn’t changed my personality, because we all know lead singers can be very difficult. [Laughs.] The thing is that the LPs were a great way of me getting to listen to the music, because when I’m singing I don’t really listen to the music. And it’s been nice for me to hear what the boys do. They play very well. I’ve played with them off and on since 1990.

I’m very happy that guy [Steve Beatty] came along on that night. It was a real twist of fate, if you like. I never expected it to snowball in the way it has. It’s been fantastic. It just shows you that, as a musician in this world, you really do have to keep plugging at it, because even for me, with 41 years now of being a musician, I’m still coming across people who can be very handy. So, yeah, the best advice you can give any musician is to keep going.

YouTube It

Peter Hook displays his melodic style of bass playing during the grand finale of a September 2013 gig in Mexico City in a rendition of the Joy Division classic “Love Will Tear Us Apart.” As the song unspools, the audience picks up the melody and Hook leaps off stage.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)