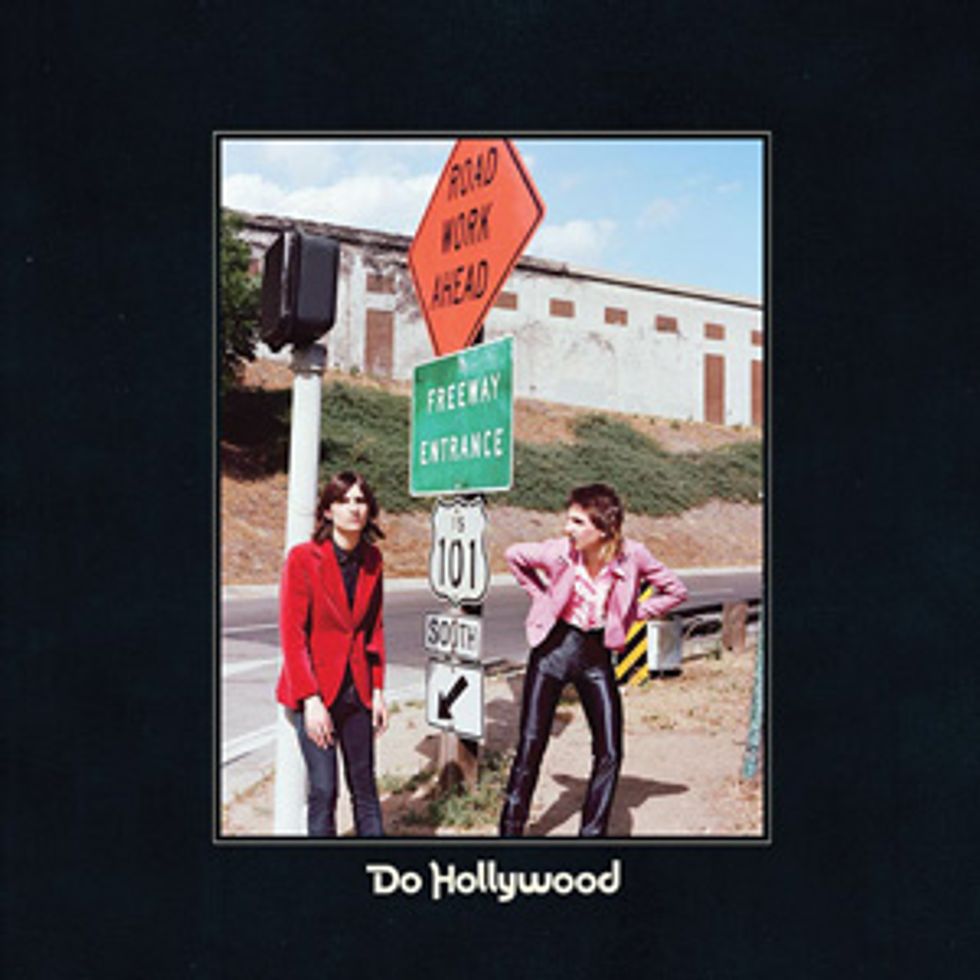

The Lemon Twigs’ debut LP, Do Hollywood, is an impressive album from any angle. Rendered in a distinctly ’70s sonic aesthetic, the 10 tracks show such compositional depth and are so well-crafted that one might assume they are the work of seasoned session vets or a squad of high-profile rockers. However, the reality is far more humbling. Do Hollywood’s songs were penned by a duo of teenage brothers in the basement of their parents’ Long Island home. Moreover, nearly every instrument on the album was played by the ambitious young men.

While the ages of the brothers D’Addario (Brian is 19 and Michael is 17) certainly adds a layer of intrigue to the Lemon Twigs’ mystique, make no mistake: This is no teen-rocker novelty bit. Do Hollywood is a serious work that reflects an obvious reverence for rock’s most respected compositional minds (the D’Addarios have been influenced by Brian Wilson and Paul McCartney) without directly rehashing the past nor sacrificing the Lemon Twigs’ own unique musical persona, which fuses power-pop anthems with complex prog-pop arrangements. The resulting music is textured and mature, but carried out with a youthful exuberance and playfulness that makes it an anomaly in today’s musical landscape.

While the D’Addario brothers did the heavy lifting on Do Hollywood, the album benefits immensely from the production chops of Foxygen cofounder Jonathan Rado, who played no small role in dressing the record in its ’70s finery by tracking it to tape and utilizing his stash of esoteric, vintage equipment.

Beyond their triumphant debut release, the Lemon Twigs are an absolute force of nature in the live realm. Supported onstage by bassist Megan Zeankowski and keyboardist Danny Ayala, Brian and Michael split the set by fronting the songs each respectively wrote. Michael starts gigs on drums as Brian fronts the band on guitar, and then the brothers swap spots onstage around the show’s halfway point (both are killer drummers, for the record).

While Do Hollywood sees the guitar used chiefly as a color tool, it’s an integral part of the live show in that the brothers use it to make up for much of the album’s grandiose arrangements that are not easily recreated live. Armed with but a single vintage Gibson Melody Maker between the two, the D’Addario brothers prove they’re both deft, athletic, and tasteful players with the ability to lace their songs with tricky leads and brawny, Townshend-inspired power-chord kerrang.

Premier Guitar spoke with the power-pop wunderkinder to get the backstory on their lives as guitarists, the creation of Do Hollywood, and their philosophies as songwriters.

Tell us about your path into the guitar. Who influenced you as players, and how did you get so proficient?

Brian D’Addario: Well, the first person I really loved as a guitar player was Pete Townshend, and it was through my interest in him that I got into playing guitar solos. Live at Leeds was really influential to me as a guitarist, but I started playing fast stuff because I was into My Chemical Romance when I was younger. The guitarist in that band, Ray Toro, plays very metal-influenced guitar solos and I used to learn those. So I got good at doing pull-offs and really fast runs from listening to that band. Also, when I was 12 years old, I started taking classical guitar lessons with a teacher named Yasha Kofman, who has a school called the Classical Guitar School of New York—he’s actually the only instructor—and those lessons changed my entire approach to guitar. Playing all those classical pieces and learning how to use my right hand for intricate fingerpicking patterns really helped a lot. So I’d say those three influences and experiences got me to a different level and made me the player I am, at least in terms of technique.

I imagine learning classical guitar helped you grow as a songwriter and composer.

Brian: Oh yeah, for sure! I’m continuing to take lessons with Yasha and, the thing is, when you learn a new classical piece it actually opens up a new understanding of pop music because everything you hear has really been represented in some way before, and you start to see how it all works from the ground up. Sort of how Brian Wilson would pull things from Bach pieces and change the root note of a chord to make things more interesting. The lessons have really opened up my mind to where things come from and how songs are built. Plus, it’s just such beautiful music.

For their debut album, Do Hollywood, the Lemon Twigs’ Brian and Michael D’Addario tracked to tape using vintage gear owned by Jonathan Rado of Foxygen, who produced the record.

Pete Townshend is something of an unexpected influence for someone in your age group, Brian. How did he influence your playing?

Brian: One of the specific things we took from him—and particularly from Live at Leeds—is how he got so much range out of just one guitar on that album, and he didn’t really use much in the way of effects. That’s become our approach—using a simple setup and milking what we can from it. As far as his playing goes, he’s not as virtuosic a player like Clapton or a lot of his peers, but I feel like Townshend’s solos just have so much personality and they always tell a story. He knows when to stop playing and he knows what tools to use at what time, and I try to be tasteful like that myself.

And where are you coming from as a player, Michael?

Michael D’Addario: Not necessarily someone you’d immediately hear as an influence in our music now, but the first person that I saw play guitar that made me think I could do it was Kurt Cobain. When I was in middle school, I was a huge, huge Nirvana fan. I still love them—but I listened to them so much that I almost can’t listen to them anymore, you know? I played drums from age 5 until age 13 and I never thought I was capable of playing guitar until I heard Nirvana. I actually picked up a bass first and learned “Smells Like Teen Spirit” and it started to click, and that’s how I really got into playing guitar. Then using the basic chords my dad showed me. The biggest these days is definitely Alex Chilton, and then probably Joe Walsh—I love to reference Joe Walsh in my playing. I’ve actually learned a lot of his licks and incorporated them into my own solos. Brian was talking about Pete Townshend not needing anyone to back up his songs for them to work, and Chilton’s got that same thing where he can accompany himself really well on guitar. As a soloist, he used a lot of open strings and tricks that took up a lot of space in a cool way, and I love that idea.

Could you expand a little on what you’ve taken from Joe Walsh?

Michael: Well, there’s a big lick in the solo of a song called “Queen of My School” that we close our live sets with—it’s going to be on the next record—that I lifted from Joe Walsh. I feel like if you learn “Life’s Been Good,” then you’ve got, like, 80 percent of Joe Walsh’s licks, and the one I picked off of him is a really Walsh-specific one that I haven’t found anyone else using. I just think he’s got this great, expressive style.

Onstage, the D’Addario brothers take turns fronting the band on a shared guitar and hopping behind the drums. Here Brian lays into his brother’s ’64 Gibson Melody Maker. “I really want Brian to get one of his own,” says Michael, “so he doesn’t have to use mine live. It’s my guitar, you know?”

Photo by Matt Condon

The record has a unique sonic personality and the production obviously harkens back to the ’70s. How did you go about capturing that vibe in the studio?

Brian: That’s great to hear, because we were really after that. I have to credit the sound to Jonathan Rado’s production skills and the fact that we tracked to tape. Jonathan has a ton of great vintage studio gear, synths, and compressors, but that stuff doesn’t always make the process easy and he was a pro about it. The mixing console we used was really finicky and the tape machine didn’t always work so well. It was a semi-professional machine that used half-inch tape instead of 2-inch tape. The fact that Jonathan got it to sound as clean as it does with the equipment he had is a real testament to his skill as a producer and engineer. Now he has much better gear and I can only imagine what the result would be at this point.

On first listen, Do Hollywood struck me as something an early British Invasion band might have created if they’d somehow been influenced by the prog movement.

Michael: Yeah, that was certainly where we were at mentally at the time, and I still respect and love what we did in that style, but for me it got really easy to write things like that and I’ve decided since that it’s more of a challenge for me to have a little restraint, so that’s where I’m headed at the moment. Then again, if you’re into something, do it! I would never do something that felt unnatural just for the sake of a challenge, but I think the next album is going to be a little less progressive. There will still be that element, but it won’t be every song.

Brian, your songs seem to be the proggier, more complex ones. Do you typically compose your songs on guitar?

Brian: I actually wrote just about all my songs on piano for this record, other than “How Lucky Am I?,” which I wrote on guitar but is ironically actually only piano on the album. Live is a different thing and I have to make up for the instruments that aren’t there, like the synths and the strings, and I use the guitar to do that a lot. It’s exciting and a fun challenge for me to transcribe those arrangements to guitar. A lot of the time I have to use the guitar to fill out the sound live to compensate for not having that big arrangement. The other thing is a lot of the guitar parts on the album aren’t that substantial, like the chorus of “I Wanna Prove to You” has a guitar part that’s just a little single-string melody, which doesn’t service the entire song live.

—Michael D’Addario

What guitar gear did you use for Do Hollywood?

Brian: We used all of Rado’s gear in the studio. We didn’t bring any guitar gear of our own. We used Rado’s vintage Fender Telecaster for most of the guitars, and we also used an old Hagstrom 12-string electric a lot. Oh! And there was this weird, cheapo hollowbody from the ’60s that had only a neck pickup—I think it was maybe Japanese—but it has a unique sound that’s somewhere between an acoustic and an electric. We used that a bunch. You can hear it at the end of “A Great Snake.”

Though Do Hollywood isn’t necessarily a guitar-driven album, the instrument is used to add a lot of counterpoint and color. Do you have a specific approach to how you apply that—especially considering how the live show is so guitar-heavy?

Brian: There were times in the demoing process when I tried to use the guitar in a similar way to the guitar parts on certain Beach Boys records, specifically The Beach Boys Today! or Pet Sounds—records in which the guitar parts are very planned out and there isn’t much room for improvisation. I try to use it in the way you’d use orchestrated string instruments, and if I do throw improv parts in, they’re textural and typically just there to add fullness. But the prominent guitar parts are very thought-out and I usually try a few different options before settling on an idea.

Can you point out any examples of improvised textures?

Brian: I think the best one is on “These Words.” In the second verse after the chorus—it’s kind of subtle—but in between the vocals, there’s a Moog synth, and there’s some very clean electric guitar complementing what the Moog plays.

Describe the Melody Maker you both use live.

Brian: Well, that’s Michael’s, and he got it on eBay. I was very skeptical of using eBay to buy instruments ever since Michael bought this tiny Supro guitar. He didn’t know it was tiny until it arrived, and he had already paid $600 for it. I think he could have returned it, but he was all like, “No, it’s great! It’s great.” I think he wanted a new guitar so bad that he just settled for it, and it’s never gotten any use. So I wasn’t very confident in the idea of getting a vintage Melody Maker off of eBay, but it turned out to be a really great decision on his part because it’s a great guitar. Michael wants me to get my own, but it’s hard to bring myself to because this particular one is so wonderful.

D’Addario brothers’ Gear (shared by both)

Guitars1964 Gibson Melody Maker

Amps

Early ’60s blonde piggyback Fender Bassman

Effects

None

Strings and Picks

D’Addario (no relation) EXL110 sets (.010-.046)

Medium picks with no brand preference

Michael: It’s funny, because I bought that Melody Maker not really understanding the sound I was going to get out of it. I didn’t know that much about pickups when I got it, and I didn’t realize that the single-coils that came stock in those guitars have almost a Strat-y sound. I was always on the internet looking for old guitars. I wanted something vintage and I loved the look of it, but I was after more of a beefed-out growl, like what Joan Jett gets out of her Melody Makers—not realizing that her guitars were modified. So I bought the thing with that in mind, and when I got it I was like, “Whoa, that’s not what this guitar is at all.” I was a little unhappy about it at first, but it happened around the same time I started getting into Big Star and I realized that it worked perfectly for what I

was going for at that point. I love it even more than my dad’s ’67 SG, which has always been our measuring stick. We’d always buy new guitars and wind up going back to that SG because it’s such a cool guitar. But this Melody Maker is the one for me—it’s my guitar, you know? I’m pretty possessive of it and it means a lot to me. I actually really want Brian to get one of his own so he doesn’t have to use it live, and I tell him so all the time.

Have you modified the Melody Maker?

Michael: No, that’s how it came to me. The tuners are replacements, and the bridge was changed out for sure because it has the three holes where a Vibrola would have gone. That’s something a lot of people did in the ’70s, because the stock tuners and those Vibrola units were pretty bad at holding tuning.

Pete Townshend has influenced both Brian and his younger sibling, Michael, shown here giving an exuberant Who-inspired kick while digging into the band’s communal 6-string. Photo by Matt Condon

Brian: That Bassman comes from a friend of our dad’s. He was tired of having it in his house and said we could have it on a permanent loan, so we took it all over America! It’s a great amp. We don’t use any effects live, so it sort of informs how we play and adds some power to our style and changes the choices we would make, I think. For example, when we play the chorus of “These Words,” the part on the record is very atmospheric and has a bunch of delay on it, but live I have to do this kind of smooth, arpeggiated part to make up for it and get the same mood.

How would you guys contrast your personalities as players and songwriters?

Brian: Michael started playing guitar when he was 13, and I started when I was 7. I’ve been through a lot of phases and I’m at a point where I’m a little more excited by instruments I haven’t had around for as long. But Michael has such a love for the guitar right now that there’s a real excitement in the parts he brings to the table, so where I have a lot of knowledge and technique from playing it for so many years, Michael has a lot of exciting ideas that I think only come from being as deep and passionate about the instrument as he is at the moment. So, a lot of the time, we complement each other in that I can execute some of his ideas and he can inspire some of mine with his excitement.

Michael: I don’t know if people realize how good Brian actually is as a guitar player. He’s a whole lot better than me! But we just have a different vibe, and I feel like the things I gravitate toward playing I do better than he does, and he’s got that speed and power from his early influences.

At the time we recorded the album, neither of us minded going off on musical tangents and doing things like throwing in time changes whenever we pleased—which is cool and can be interesting—but these days I’m more focused on writing songs that are interesting and unique while staying in the same place, simplifying things a bit without relying on time changes and tangents like that to add interest. I think Brian is still a bit more interested in the progressive style we had been working on when we wrote this last album—which is great, and something I like—but maybe not where I’m presently at so much as a writer. I feel like now I’m trying to prove to myself that I can write a song that doesn’t need too much movement to hook you in and keep your attention—like early Beatles songs do.—Michael D’Addario

So artistically speaking you’re already moving past how you approached Do Hollywood?

Michael: Most of the songs on the record have that thing where they go through lots of different movements and changes—at least my songs do for the most part. Brian actually has “How Lucky Am I?,” which I’d say accomplishes what I’m after now. It’s a beautiful song that doesn’t travel too far from its main point. I guess “As Long As We’re Together” is one of mine on there that doesn’t rely on taking you to a billion different places to do its thing. To me, time changes and jarring movements in songs feel like an easy way to keep someone’s attention and are a little bit distracting.

Do you have any sort of overarching philosophy as a songwriter and composer?

Michael: I think it’s pretty much the same for Brian and me. I just want to write songs that stand on their own. We’re firm believers in the acoustic guitar test: We want our songs to work and come off well without all the bells and whistles—just performed with an acoustic guitar or piano accompaniment, you know? I also try hard to write things that don’t remind me immediately of someone else’s stuff, which isn’t always easy.

How did you two divide up the job of playing bass on the album?

Michael: We pretty much played bass on our own songs. I don’t think there are any that we switched on.

I really love the bass tone on “Baby Baby.” How did you get it?

Michael: That’s a ’60s hollowbody violin bass strung with flatwound strings. It’s an unbranded one, but similar to a Hofner. Half that song is also palm-muted, so it gets that chunk even more than just with the flatwounds. I remember for years not understanding why I couldn’t get that specific tone—even when I muted the strings—and I finally learned that it was the flatwound strings and it makes all the difference. So that bass is on a lot of the record. We also used a huge Silvertone bass with roundwound strings for a lot of really deep tones, and we used a Rickenbacker bass with roundwounds for some deeper sounds. But for most of that “plucky” stuff, it was the violin bass. I’ve also started focusing on my guitar tone a lot more, especially since making the record.

How so? What have you started doing differently?

Michael: Brian used to set up the amp for his sound live and I’d just roll with it. When Brian goes to take a lead, he just flicks the pickup switch and has it set up for his sound, which is usually a little quieter, clean sound. Then he also sets up a really huge lead sound, because he does a lot of big, sustained notes when he solos. For myself, I like a little more restrained sound that’s in the middle most of the time, so I’ve been focusing on getting a nice crunch sound on the cleaner side. I’m trying to tailor our amp settings more to my style when we switch, which I hadn’t done live in the past.

Do you guys ever talk about fronting the band at the same time?

Michael: Yeah, we talk about it all the time and we’d love to do that! We just haven’t found anyone who can pull the drums off the way we do.

YouTube It

The Lemon Twigs give a rousing show at Amoeba Records in Los Angeles, with the D’Addario brothers taking turns on drums and their cherished ’64 Melody Maker.

In this spirited live-in-the studio performance, Brian D’Addario pounds the kit, while brother Michael is out front on guitar. In the background, you can catch glimpses of the band’s ’60s piggyback Fender Bassman. “It informs how we play and adds some power to our style,” says Brian.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)