Jack White is always on the hunt for the hard way out. For decades he’s battled difficult pawnshop guitars and found trailblazing ways to make them growl, howl, and sing. White uses both experimenting and limiting as techniques. He might impose strict parameters on a project, or work in weird color schemes or numeral obsessions. For all the eccentricities, the man has no fear when it comes to artistic adventure. From the White Stripes to the Dead Weather to collaborating with pop titans like Beyoncé, he goes for it. But for the Raconteurs’ third studio album, Help Us Stranger, he did something ironic and starkly less intense than what he’s known for.

“The funniest thing on this album was that there’s something that happened that I’ve been avoiding my whole life in recording,” White shares. What did he do? He played a Les Paul through a Fender Champ. The yin to that yang is his new affection for using a B-Bender, G-Bender, and E-Bender on a Fender Telecaster.

On the whole, the Raconteurs’ vibe is lighthearted and communal, in the spirit of traditional rock bands as a unit. Co-frontman Brendan Benson, White’s writing foil who shares the Raconteurs’ canon authorship equally, says it’s “classic Raconteurs” modus operandi for the band to fly by the seat of their pants, improv their asses off, and somehow have things fall together in a mystical way that they have a hard time putting into words. “I’m kind of kidding,” Benson says, “but with the Raconteurs, it’s like, how far can we go with not playing the song?”

Benson’s knack for clever, deep songwriting paired with White’s bull-in-a-China-shop 6-string prowess is a palpable force. White brings explosive riffs and Benson provides the segues. Jack White is a lead guitarist; Benson is a glue-it-all together player who can do it all, from rhythm to slide to synchronized, ripping chords with White through a bridge to blues harp ad-libbing, all on a dime. Benson's keen sense of melody is evident in his vocal style, which the guitars in a Raconteurs’ joint often mimic. The inventive tones on the album will leave no 6-string enthusiast wanting. Help Us Stranger’s single, “Sunday Driver,” packs a punch of guitar ideas, with White’s experimental Flex synth-fuzz pedal spiraling into an octave-changing intro riff, while Benson hits arpeggios in the verses.

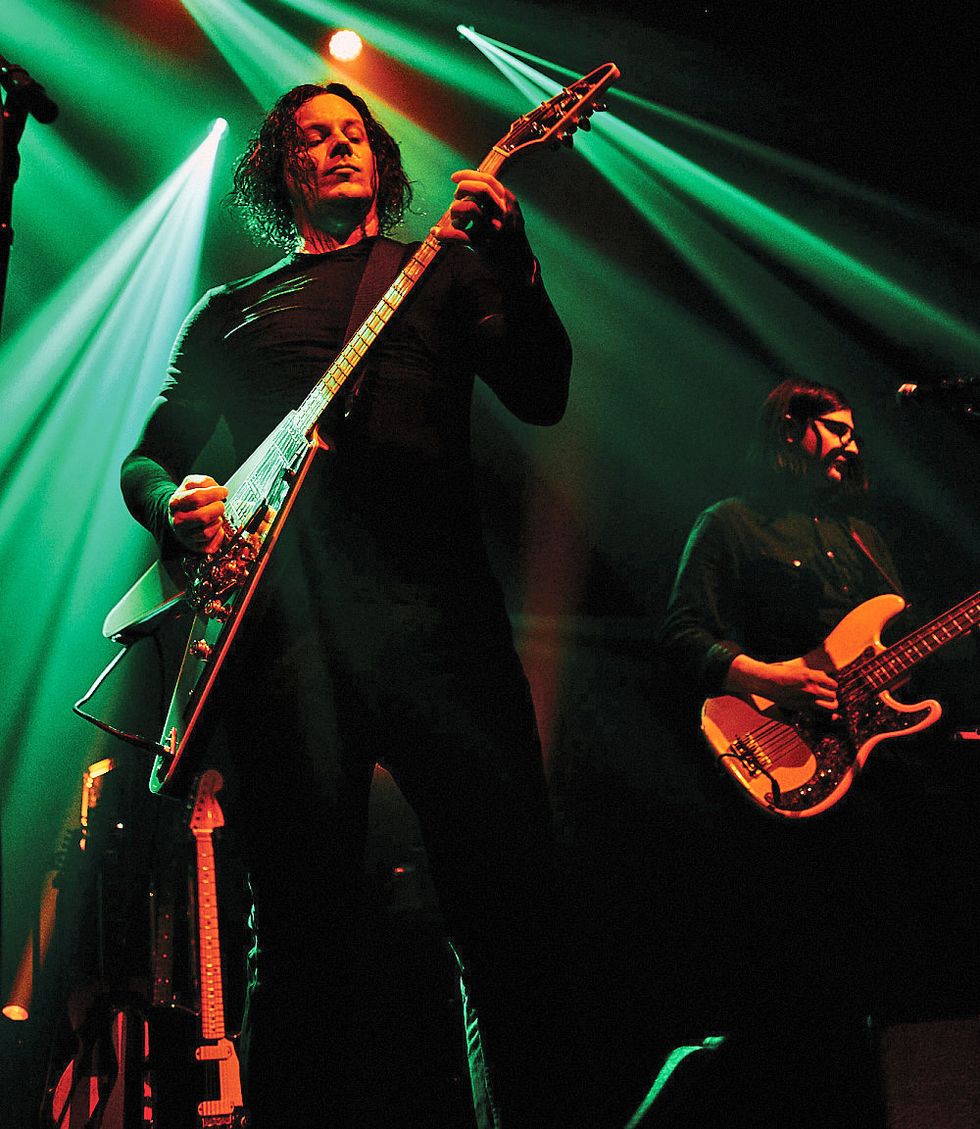

And look: White’s rocking a Flying V now, too.

Help Us Stranger was produced by all four of the Raconteurs: White on lead guitar and vocals, Benson on rhythm guitar and vocals, “Little Jack” LJ Lawrence on bass, and Patrick Keeler on drums. (Dean Fertita plays keys/percussion at live shows, and he’s also a member of another White-inclusive band, the Dead Weather.)

The new album comes more than a decade after the Grammy-winning sophomore release, Consolers of the Lonely, and misses no beats: It’s constant motion, formidable swing with impeccable timing and phrasing, light-dark storytelling, and an intangible quality that shows up when groups have unflappable chemistry, like … dare I say—the Beatles.

For all of the Raconteurs’ raging musicality, a specialness reveals itself in the emotional conjuring of existential struggle expressed in their lyric themes. “I think I suggested ‘Help Me Stranger’ because it’s so powerful,” Benson says. “We didn’t talk about why or what it was. I think it’s just one of those evocative statements. And then, of course, we decided to pluralize it to make it Help Us Stranger, since all the other records kind of had that gang mentality about them, like soldiers and consolers and strangers, or ‘us.’”

White calls Benson the best songwriter out of the Detroit scene they both grew up in. Both White and Benson are also drummers, and it’s fun to look at the teenage influences each guy cites and throw it up against the space they inhabit in the band. White was into Deep Purple, Emerson, Lake & Palmer, Dylan, the Cramps, and the Flat Duo Jets. For Benson, it was the subversive hardcore punk movement on Dischord Records (Minor Threat, S.O.A, Dag Nasty) and Black Flag, paired with what his hippie parents played at home: the Stooges, T. Rex, Bowie, Roxy Music.

It all makes for an interesting variety in their sonic journey. “When we were mixing the record I thought, ‘Wow, these songs are little odysseys,’” Benson says. “They take some turns, and there are some definite departures and coming-back-agains. Even tempos going up and down.”

From their home base of Nashville, White and Benson candidly discussed the making of Help Us Stranger and the artillery they used, from White’s new trio of “golden Gibsons” and the “contraptions” he’s putting on all his guitars to the pair’s creative synergy, and how making Raconteurs’ music has given them some of the most thrilling times in their lives. Spoiler alert: It all smells like rain, leather, hair spray, and clove cigarettes.

Are you in Nashville today?

Jack White: Yes, we’re home for a little bit of regrouping. We just came back from Australia and Japan, our first shows over there. Yeah, I’ve been feeling good.

I live in Nashville too. You know the Natchez Trace Parkway? That’s where I drive to listen to new albums because there’s no traffic. I listened to Help Us Stranger that way and it’s my new driving album. What’s your favorite way to listen to new music?

White: Yes, I love it. That’s a nice idea! I have to say the car. I don’t have a cell phone, so I’m undistracted there by anything. Nobody can come in and ask me anything or take me away from what’s going on. It would be hard at my house to listen to an entire album without some kind of interruption. There’s always so much stuff going on. So it’s really nice. I’m lucky enough to drive a Tesla, and I really think it has the best sound system of any car. The factory sound system is just outstanding sounding. It still impresses me years later, the sound system in this car.

Brendan Benson: I usually like to be doing something, like cleaning up or driving, or in the headphones. That’s always a good one: Go for a walk with the headphones. I rarely just sit down and put on a record and stay put, unless it’s a vinyl record. Then, of course, you can’t wander very far.

You guys are both from Detroit. How did you first meet?

Benson: I just went up to him and introduced myself. I was floored by the White Stripes. I couldn’t believe what I saw. I was living in California at the time. I came home to visit over Christmas or something like that and some friends took me out to the Gold Dollar and the White Stripes played. I was asking my friend, like, “Who’s this guy? What is this?” Oh, it’s this guy Jack. Jack and Meg, they’re from the West side. I think I offered to record him. I had recording gear and kind of a cool home-studio setup. I think I just said come on over and record some of your songs at my house. Which he did. I remember we did a few of his songs, which I just recently gave back to him. He was really not shy. I remember that. I remember thinking, “Wow, sweet! He’s serious.”

It’s been a decade since Consolers of the Lonely. How did you know it was time for new Raconteurs music and to get writing?

White: That’s the hardest question to answer lately. None of us could really remember why we started playing again. We also don’t know why it took so long. It’s very strange. The easy answer is to say that we’re all very busy. I’m starting to think that there was this song called “Shine the Light on Me,” which I had recorded for my last solo record. It just didn’t fit all the other string songs on that record. I thought, “Y ou know what, this really does sound like a Raconteurs song.” I might’ve played that for Brendan and said, “You know, I’m going to save this for the next time we record together.” That might’ve started it. I’m not sure.

The Raconteurs third LP, Help Us Stranger, was produced by the band, recorded and engineered by Joshua Smith, and mixed by Vance Powell at Sputnik Sound in Nashville. It’s the 600th release on Jack White’s Third Man Records label.

You both collaborate with a lot of people. Sometimes a musical marriage or mixture works amazingly, but it’s just once, or maybe for a short time. What is it about this band that has given you longevity?

White: It’s probably because we’re all from the same area. We came out of this Detroit garage-rock scene that was happening around the late ’90s. Brendan was the best songwriter of the whole group. He was really not garage rock-y, but more of a singer-songwriter. He was somebody we looked up to a little bit, because he got signed first. He was signed to Virgin, and he released a solo record on a major label already, and the rest of us were all on these tiny little bedroom labels. He had a whole different lifestyle of music than the rest of us did, but he also really loved the White Stripes and the bands I was in, and the Greenhornes—Patrick [Keeler] and LJ [“Little Jack” Lawrence], their band. It was very cool. If I could’ve picked who I’d be in a band with, of all the people in this scene, I’d say that I’d love to be in a band with Brendan and the rhythm section of the Greenhornes. That’s what happened! I couldn’t have picked it any better.

Benson: It’s one of those collaborations that just works really well. Not to compare ourselves with them, but like Lennon and McCartney. I think they were great for each other. Very complementary. They knew. Me and Jack both have the same musical sensibilities. So, it really works. Not just that we’re able to finish a song together. I mean, I’ve written with a lot of people since Jack. Jack was the first guy I ever wrote or collaborated with. I’d never even thought of doing something like that. It’s a very personal thing. I think he thought that way as well. When we wrote together, it stayed personal. I’ve written with people since, and you’re kind of coming up with lines, coming up with words, coming up with choruses and chords and stuff. You might get a song that’s pretty cool or whatever. More often than not you’re lucky to have finished it. I think that’s probably why. It’s just a good chemistry.

When you write together, are you guys in the same room? Would you say the songwriting duties are pretty evenly shared?

White: All different things. We try to shake it up as much as possible. Sometimes one of us does 90 percent of it, and sometimes it’s very 50/50. Each song is different. Sometimes we finish them in the studio together, or sometimes the other person does almost everything. You don’t really have to touch it. You almost just add production or instrument tones to the idea of it to help flesh it out. You just have to do what the song is telling you to do and not let your ego get involved too much. We also don’t have that competitive thing going on very much, like that Lennon-McCartney competition style. I sometimes wish we did. It might be interesting to see what would happen, but I think we have a mutual respect for each other. We just like to inspire one another.

Benson: I had some ideas laying around that I thought would be great for Raconteurs, and I had them laying around for years actually. So did Jack. We’ll kind of come together…. It’s only been three records, and it’s different every time. The one thing that has remained constant is that we’ll each have a couple of ideas to bring to the table. It’s nice to have someone else help you finish them. It’s great. That’s my problem. I have a lot of unfinished ideas. Hearkening back to the lack of competition between us, I think, in fact, we look forward to someone else helping us. We can rely on each other. It’s really great to be two singers and songwriters, because you have your songs that you sing, and then you can step back and take a breather and play guitar. It’s really a great thing. I think the shows can be better. They can be longer, simply for endurance purposes. If I had to sing all those songs myself, there’d be no way! The set would be 20 minutes.

The Guild Aristocrat is Brendan Benson’s favorite guitar. His 1959 model is shown here, but for the upcoming Raconteurs tour he’s got an early ’60s black Aristocrat and two thinline T-styles made by Charles Whitfill. Photo by David James Swanson

How much of this album was written on guitar?

White: Good question. I would say most of it. I don’t remember too many piano songs for me. “Shine the Light on Me” I wrote on piano. But most of them on this album are more guitar-based.

Benson: Usually it’s acoustic guitar, because that’s my go-to and it’s easy. But I do like to sit at the piano sometimes and see what happens. I don’t usually write on electric guitar. A lot of times I write on drums, actually. I have a solo record that’s done that will come out later, and I wrote a lot of those songs on drums. I just sit behind the drum set, and I can hear the song a little bit in my mind.

If you’re at home just playing around writing stuff or jamming, what guitar do you pick up?

White: Well, most of the time I have this Gibson Army Navy guitar from World War I. I played it a lot in my solo live shows. I probably shouldn’t have, because I’ve scratched the hell out of it. It’s really comfortable. It has a thick V-shaped neck, sort of like a baseball-bat thick neck. It’s very soft and bass-y and comfortable. I really like that. I don’t really like bright acoustics too much when I’m sitting around.

Where did you get that guitar?

White: I got that in St. Louis at a place called Killer Vintage. I’d never heard of that guitar, the Army Navy. They made it for soldiers in World War I. It’s supposed to be like a no-frills version of a Gibson L-1. By the time they finished making them, the war was over, so they didn’t really sell that many of them. It was supposed to be like a cheap, no-frills guitar to have at army bases. It has a great sound.

What about you, Brendan?

Benson: My Gibson Country Western. That’s been my guitar for years that I’ve always played and written on. Lately there’s a new horse in the running. It’s a Gibson J-45 gold top. I think it’s a custom shop. It’s a very limited-edition guitar that I found in Detroit and it has a gold top like a Les Paul, so it’s really bizarre.

Jack, you’ve talked about how your decision to play an EVH Wolfgang was after Eddie Van Halen mentioned that he doesn’t want a guitar to fight him. Now you’ve got the Fort Knox Gibsons, and are playing a Flying V. Where are you at with these experimental guitar changes that you’re trying?

White: It was just sort of two types of guitars. I had an army of guitars for this Raconteurs album and for the touring. The most guitars I’ve ever taken with me on the road. I almost don’t know why, except for how many different tones and ideas that we tried out in the studio. It’s sort of these new Telecasters and these golden Gibsons. The Gibsons were given to me as a present by Gibson. There was some Grammy event that was sponsored by them, and they said, “Pick out any guitar you want!” I said well, I usually only play Gibson acoustic guitars. I didn’t really know what to pick. I saw this Fort Knox gold Les Paul in their catalog, and I thought that’s crazy, it’s so gold! I wonder if they’d make me one of those with a maple neck. I didn’t know if they’d do that or not. They were nice enough to do that. They gave me the Flying V with the maple neck as, like, a second guitar, as a present. That was really kind of them. I like the number three, so I said, I wonder if you could make me another one: the Firebird Gold with the Fort Knox maple neck? So I had those three guitars.

And then I had these two Fenders. I was given a Fender B-Bender for Christmas. I played that on this song on the album called “Somedays (I Don’t Feel Like Trying).” It was the first time I ever played a B-Bender on a recording, and I really loved it. I have another 1982 Telecaster that I equipped with a Hipshot B-Bender, and this other one. The Fender Custom Shop was being really kind to me. Chip Ellis, who helped make that Wolfgang guitar for me last year, he’s been making and customizing these guitars for me, these Fenders. He got me the new Acoustasonic Telecaster, which was the first one out of the Custom Shop that they’d done.

That’s been really helpful onstage, because you can switch from acoustic to electric in the middle of the song. I’m using that a lot onstage. Then this other one, this B-Bender that I really customized and put new pickups and all these contraptions in… I can bend the high-E string, I can bend the B with the strap, I can bend the G string, and then I can drop-tune the E with this flip-switch, which is something that the Wolfgang guitar did that I wanted to carry forward. So it’s sort of making these new guitars full of contraptions. It’s really, really interesting.

The Acoustasonic Telecaster is an interesting concept.

White: It just came out a couple months ago. It’s brand new. It’s very interesting. In Nashville especially, I think they’re going to sell a million of them, because if you’re a guy who plays up on Broadway or something and you’re doing a four-hour set at a honky-tonk, this guitar would really help out. You can make it sound like seven different things without even getting out of your chair.

What guitar do you think you’ll be playing the most for the Raconteurs tour?

White: Probably that Telecaster with the B-Bender and all the contraptions on it. It sort of has everything I need. It also doesn’t have a Bigsby on it. I don’t know if I’m going to be able to conquer these Hipshot G- and E-Benders that I’ve put on there. They’re tricky. It’s a whole new thing. It’s almost like a pedal-steel guitar, really. I’m trying to give myself these challenges to see if I can come up with something that I haven’t done before, to find out what parts I like. It may end up turning into a Bigsby by the end of the tour. I don’t know.

How did you get turned on to the B-Bender?

White: The B-Bender was something I always thought was cool. I’ve seen country artists use it. Jimmy Page used it in “All of My Love,” I think. My friend got it for me for Christmas, because they knew that I’ve always wanted one. It came in right at the perfect time, because we were recording the song “Somedays,” that Brendan had. The bend that it would do is exactly the bend Brendan was doing with his voice. It was pretty cool to do it at the same time. It was perfect timing.

Tell me about the interrupter switch on your St. Vincent Music Man guitar.

White: I have that on all my guitars now. I can’t resist it. I just love it. I used to have an on-off toggle switch to turn the guitar on and off. That’s a lot harder to use. But they didn’t have those interrupter switches when I first was customizing my stuff. You can just hold it down and fix whatever you need to. It’s very cool, man. You can do really great things. I used to do recordings with a tremolo or something where you’d interject it and sometimes go into Pro Tools and print the tracks to tape. I’d slice it up. On the second Raconteurs album, I’d slice the guitar solos up with tiny spaces. That interrupter can mimic that live.

Guitars

1959 Guild Aristocrat

Early 1960s Guild Aristocrat

Charles Whitfill Thinline T-Style (two: one natural, one sea foam green)

Gibson J-45 Gold Top LTD (acoustic)

Amps

Marshall JTM45 Offset

Silvertone 1484 Twin Twelve

Effects

Whirlwind Phaser

Caroline Kilobyte

Way Huge Angry Troll Boost

Strings and Picks

D'Addario strings (.010–.046)

Herco Flex 75 mm picks

Glass slide

Hohner Marine Band Harmonica

Brendan, you play Guild Aristocrats. Is the black one you’re currently using new?

Benson: It might be a ’60 or ’61. I got it several years ago, but I never played it. I had it in my mind that there was something wrong with it. It doesn’t sound as good as my blonde Aristocrat, but something happened, or else I got it totally wrong, because I picked that thing up before making this record. I just plugged it in, and wow, it sounded fucking great. What was I thinking? I was probably playing it through a weird amp.

Then you have a Thinline T-style as well.

Benson: Yeah, I have this Charles Whitfill Thinline [T-style] that’s fucking awesome. It just plays beautifully. The pickups are amazing. They sound crazy good. That guy, Charles Whitfill, is a badass. I was going to say I don’t know why he’s not more well known, but he’s only one guy making guitars out of his house in Kentucky or something.

One of my favorite lyrics of the album is “Somedays (I Don’t Feel Like Trying).” It starts out hopeless and then it ends with, “I’m here right now. I’m not dead yet.” Almost hopeful.

Benson: Right. That whole end part was totally off the cuff. The song was proving to be difficult to record. We were all under headphones and playing. The song’s kind of mellow, so we’re all playing mellow. It was a very nerve-wracking song to do. Maybe nerve-wracking’s not the right word, but it was tedious and kind of tough going. On one of the takes, I started playing that guitar line, just that guitar part, and everyone started joining in. I said that line—I don’t know where that line came from even. It was one of those, in my mind, magical things that could only happen being in the Raconteurs. It was one of the most exciting times in my life! Maybe that sounds too dramatic, but that’s the kind of shit that I live for, you know what I mean? Impromptu and it all came together. I’m really proud of that one.

Do you have a certain way you like to record your guitars?

White: I like to try something different every time. The funniest thing on this album was that there’s something that happened that I’ve been avoiding my whole life in recording. Probably one of the number one things in the studio is, people would say, either a Les Paul or a Stratocaster played through a very small amplifier. Those are things that you can do to make a sound that is very appealing to people. A lot of people use that type of thing, and I’ve always avoided it. Oh, I’m not going to do that at all. I’m going to use these gigantic amps, really bad guitars, and try to fight them both and see if I can make something different-sounding out of it. This album, I actually had that gold Fort Knox Les Paul, and I had a new Fender Champ amp. I thought I’d try it. I’d never actually done that with the Les Paul through this tiny little amp. For that guitar solo, it was like, “Oh my god, it sounds so good!” I just thought, of course, this is why everybody does this. It’s hilarious that I’ve avoided this my whole life.

That’s crazy. You’ve been using 15" speakers for a long time.

White: Yeah. I really, really love 15" speakers. That’s the speaker for guitar playing for me. I have loved it for years. In the White Stripes, I had an 18" speaker. I learned later on that a lot of guitar players I love or who I think have good tone also use 15" speakers, like Duane Eddy and Stevie Ray Vaughan, and I think Link Wray might’ve also. I’m not sure. But there’s something I read about; it’s a thing. There’s a club of us guys, I guess, that love the 15". The 15" Fender Vibroverb is, I think, the best amp Fender ever made. It’s just perfect.

Photo by David James Swanson

Do you recall any surprises in the studio, or do you have a favorite memory from the making of the album?

White: There’s a song that’s going to be released as a single pretty soon, “Help Me Stranger.” We filmed the video in Japan. At the beginning of it, LJ—Jack Lawrence, the bass player—was in the tracking room. He was going to overdub a background vocal. We were in the control room trying to figure something out, a compressor or something. He just picked up a guitar and started pretending like he was performing the song like a 1930s singer, like Jimmie Rodgers or something. That’s who you hear at the beginning of the song. That’s just Jack and an acoustic guitar. It just sounds so great. We recorded it and actually EQ’d it to make it sound like an old 78, because his voice fit that so perfectly.

Benson: The whole record’s like that—really improv. Little Jack was in the tracking room playing acoustic guitar. No one was really listening. I remember having a discussion with the engineer, and he was kind of in the background. Suddenly, someone said, “Wait, listen!” LJ was playing the song in that kind of country way. We all just cracked up and loved it. “Oh my god, that’s brilliant! Let’s do it. Let’s use it as an intro.”

I thought that was a sample or something.

White: Yeah! People have told us that so far. They thought it was me, or an old record we found and sampled. It’s pretty funny. I don’t think LJ has actually sung on a Raconteurs recording before, like a solo. That’s pretty cool that he did that [laughing].

What’s happening with the percussion in that song?

White: It’s pretty amazing, because Patrick flips his snare drum over, and he’s sort of playing the bottom of the snare, the bottom head, just barely tapping it. He came up with this sort of hip-hop drumbeat by barely playing the drums. That was supplemented by a bongo rhythm. Then LJ played bass on it with a bass pedal: one of those [Moog] Taurus bass pedals. He didn’t play a bass guitar on that song. That’s the most unique-sounding song on the album.

Speaking of pedals, you have your Third Man + Mantic Flex. Did you use that a lot on the record?

White: We did use it on some songs. I used it a couple of times on my last solo record, too. I want to be careful not to use it too much, but it’s kind of irresistible because it does so many interesting things.

I think some people are mystified by how to use it.

White: I want to do a video with Third Man and show that. We actually have two new guitar pedals coming out that we haven’t announced yet. I can’t tell you about them, but they’re coming out in the next few months. We’ll have four different guitar pedals for sale from Third Man Hardware. The whole stable is going to grow tremendously this year, from turntables to headphones all the way to guitars.

We’re going to sell guitar strings and guitar tuners and these four really unique guitar pedals. That Mantic one was the latest one that we put out. We had the Bumble Buzz before that. I want to do a video where I play through all four of these pedals and show people how I use them and maybe see what they think.

Can you say what these two new pedals would effect?

White: I can’t tell you yet! Sorry. [Laughs.] I would if I could.

It sounds like you’re using your Flex on the “Sunday Driver” song.

White: Yes, I am. I start the song off with it, actually. Live onstage, I have to give that to Dean Fertita. He has to play the Mantic on that song, because I can’t do the other arpeggio-sounding octave thing on the guitar at the same time. I overdubbed both of those when we recorded. Brendan is playing something totally different as well. That song’s got a lot of guitars on it.

Yeah! I was wondering how you were going to do it live.

White: There’s a thing somebody sent me, because I use a Whammy pedal. I’ve always used it since the White Stripes, but this is a new contraption [called a Step Audio Riff-Step] that you can hook up to the Whammy pedal to bounce between four different settings whenever you tap it. That’s going from an octave up to a fourth down to an octave below to a fourth up or something. It just kind of worked out for that song in a cool way. Now I have to do it every time [laughs].

“Now That You’re Gone” has a call-and-response thing at the end, where the guitar pans. It sounds simple, but what’s happening there?

White: That’s very hard! We laugh every time onstage, because it’s so difficult for Brendan and I to play it properly. We’ve rehearsed it a lot, and at soundcheck we’ll stand next to each other and try to rehearse that back and forth. It’s almost like math rock or something. We still haven’t perfected it! But when it works, it’s really cool. He’s in the right channel and I’m in the left, I think.

You guys are both doing those parts in real-time?

Benson: Yeah! That was a funny moment when he did his part and I went to overdub my part. That’s classic Raconteurs stuff in my mind. On my solo stuff, I would make it way easier on myself. First of all, I would overdub the part, and I would never play it live like that. But in Raconteurs, we performed it on the record, and it’s performed live just like that. Jack’s a stickler for that kind of stuff. “Well, that’s how it’s done on the record, so that’s how we’ve got to do it.” Much to my horror, because that stuff’s very weird. It’s very hard to play. It’s not super hard to play, but it’s like, why are we doing this? The timing, yeah.

Guitars

Gibson Les Paul Fort Knox (with maple neck)

Gibson Flying V Fort Knox (with maple neck)

Gibson Jeff “Skunk” Baxter Fort Knox Firebird (with maple neck)

Fender B-Bender Telecaster Custom (with Hipshot B-, G-, and E-Benders)

1982 Fender Telecaster Custom (with Hipshot B-Bender)

Fender Custom American Acoustasonic Telecaster

Randy Parsons/Gretsch Triple Jet III

Gretsch Custom Duo Jet

Gretsch Rancher “Claudette” (custom acoustic)

Gibson Army Navy Special (WWI-era acoustic)

Amps

Silvertone 1485 (15" Jensen speakers)

1964 Fender Vibroverb (15" speaker)

1980s Fender Champ

Effects

Boss TU-3 Chromatic Tuner

Boss NS-2 Noise Suppressor

Third Man + Mantic Flex

Third Man Bumble Buzz

DigiTech Whammy DT

Step Audio Riff-Step

Electro-Harmonix Big Muff Pi

Electro-Harmonix POG2

Keeley Caverns

Demeter TRM-1 Tremulator

MXR Micro Amp

Strings and Picks

Strings: "Doesn't matter to me"

Picks: "Hard" ones

You covered a Donovan song, “Hey Gyp,” and it’s got the Animals’ version vibe to it. What made you want to do that song?

White: There’s this technique I’ve done over the years that is sort of a good idea and not a good idea. It happened on this song “I’m Shakin’” that I recorded a few years ago and this song “New Pony” by Bob Dylan that the Dead Weather did. The idea is that when we first come into the studio for a new session, let’s pick a song to cover. Any song is fine. Just someone say something out loud, and let’s cover it to get us inspired and moving. Then we can take that energy and move on to one of our own songs and see if we can carry it over. I’d just heard “Hey Gyp” on the radio in the car that morning, so I asked if anybody knew that song. Brendan says, “I love that song. I’ve always wanted to record that actually.” I said, “Well, let’s do it now and see if we come up with something interesting.” Everybody ripped into it really fast. Brendan pulled out a harmonica and played the harp on that song. None of us even knew Brendan played harmonica. He surprised all of us.

Jack, how do you feel about talking about your pedalboard?

White: I feel fine about it [laughs]. What’s cool about the Raconteurs is I have a pedalboard that’s all copper. I was fortunate enough to be able to take them apart and copper plate all of the metal boxes that the pedals come in. One of the main guitars I use in the Raconteurs is this copper Triple Jet that I sort of halfway designed. It was taking a Gretsch Duo Jet and turning it into a more contraption-filled monstrosity made out of copper. It’s just one of the colors of materials that I’ve always used in the Raconteurs, for some reason. It’s something that ties me into that band. I thought it would be cool to make the pedalboard the last time we were out, the second album, all copper. Now I’m adding more pedals to it that we used on this album. It’s actually a gigantic pedalboard. It’s getting a little bit ridiculous. I’m going to have to figure out what to do with it. On my last solo tour, because I’m playing songs from the Raconteurs, White Stripes, the Dead Weather, my own stuff, I ended up having 15 pedals or something in front of me. I only used to have two in the White Stripes: a Big Muff and a Whammy pedal. That’s all I had! It’s kind of crazy to have all of these. But in 20 years of making recordings, you have all these different tones for different solos and songs.

If music had an odor, what would the Raconteurs’ music smell like?

White: Wow. Maybe like rain. I would hope my music smells like rain [laughing]. Because when you write or record or produce something, your hope is that you’ll be able to change somebody’s mood when they’re listening to it. Say if you’re listening to “The End” by the Doors. When I listen to that song, it immediately changes my mood. They convey the mood with that song in a big way. It’s very evident. That’s an extreme example. But you can do it in subtle ways, too. The smell of rain is very subtle, when you smell outside. It’s the smell of ozone maybe, the low pressure that’s happening around you. It’s instantaneously a mood. That’s sort of what you aim for as a songwriter and producer.

Benson: There’s too much potential for a joke here.... What would we smell like? Man, geez. I think we’d smell like Aqua Net hairspray because that’s the smell of punk rock to me. That’s the smell of rock ’n’ roll to me. That’s what I remember: leather, hairspray, and clove cigarettes.

What would you say to younger musicians who are trying to find their voice?

White: I think you just have to push yourself. But also, if it’s not coming naturally, if you’re not just finding yourself picking up an instrument without even thinking about it, maybe it’s not for you. There’s this thing about art where it should be a scenario where you just can’t help yourself. You do it because you just can’t help it. That has to just be inside you naturally. You can see some people who can just naturally play a sport. They’re just born with it. That’s the case moreso than people who sat there and made themselves into a great athlete because of some other purpose. There’s that to begin with. I don’t mean that you have to be born with talent. I mean you have to be born with the obsession and the passion to even care about it. It has to be something that you can’t will to happen, so there’s that.

After that it’s sort of like … there’s a responsibility to art. You have to work at it. Once you have that passion, you have to realize that being an artist doesn’t mean, “Oh, this is great! I don’t have to work 9 to 5 like everyone else does.” No, you actually have to work harder than everybody else does, because not only are you passionate and have that natural thing going on, but you’re also applying it. You have to apply it and find a way to have it make sense to you in the real world of economics and business. Those are all very strange things to teach somebody or tell somebody. The easy way to say all of that is: just keep doing what you’re doing. If it’s going to happen, it’ll happen. If not, you just have to go with your gut.

I saw the White Stripes at Coachella in the early 2000s. That was a long time ago. You always keep changing and pushing the envelope. What keeps guitar exciting for you?

White: One thing I feel is that this is the instrument that people relate to me the best on. I really consider myself a drummer, but that’s not an instrument I think people relate to me as a songwriter with. This instrument is the one that people relate to the most, whether I like it or not. That’s my gateway to communicate. My goal is not to find the easy way out all the time—that Les Paul through a tiny amplifier thing that I mentioned and avoided for years. It’s challenging yourself all the time, like putting these Hipshot contraptions on the Telecaster, and the B-Bender, to try and make myself do something I haven’t done before. Instead of taking the easy way out, I like to take the hard way every time and see if I can get somewhere new with it. Luckily, it happens! When you come up with a new solo that you haven’t heard anybody do before or yourself do, you think “That’s great—I got to someplace new!” After all these years and songs and albums you’ve made, you’re still getting to someplace new. Even if other people don’t like it, you know in your gut or in your mind that you’ve gotten to someplace new. That inspires you and keeps you hanging on for a few more weeks, you know?

In this full concert from the Montreux Jazz Festival 2008, the Raconteurs blast through a set of mostly Consolers of the Lonely tunes. Brendan Benson and Jack White seamlessly pull off the dual-frontman, dual-guitarist formula.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)