One of rock’s great traditions—and paradoxes—is the band that revisits its roots in order to evolve. That isn’t to say the Sword have become Dylan holing up in Woodstock to make John Wesley Harding. But Warp Riders, the third album by these heavy merchants from Austin, Texas, finds the Sword indulging a subtle, but distinctly Texas-flavored sense of groove and swing. This deep-seeded part of the band’s DNA is helping guitarists J.D. Cronise and Kyle Shutt break even further away from metal convention and carve out a unique domain among modern heavy rockers.

The Sword were never easily lumped in with the modern metal pack. In the seven years since the band came together, they’ve become one of the standard bearers for a stylistically diverse and loosely affiliated society of metal-influenced bands. Along with Witch, High on Fire, and Priestess, the Sword eschews many of metal’s more aggro, cliché, and consciously flash elements and instead look to Black Sabbath’s chugging riffery and Grand Funk’s and Thin Lizzy’s backbeat-driven grooves—as well as the more melodically raging sounds of the New Wave of British Heavy Metal—to create a more soulful metal/heavy-rock hybrid.

Warp Riders is a hard-hitting refinement of that heady brew. Wrapped around a sci-fi tale (in part about a planet with one hemisphere locked in perpetual darkness), the album also links the Sword to a narrative tradition that runs from the Who’s Tommy to Rush’s 2112 and even Hüsker Dü’s pop-hardcore classic, Zen Arcade. Warp Riders doesn’t disregard the band’s metal roots entirely—not by a long shot. But check out the hooks that propel “Tres Brujas” (Three Witches)—not to mention the nod to Texas’ favorite heavy boogie kings in the song’s title—and it’s pretty clear that the Sword may have been thinking as much about tumbleweeds and greasy ribs as whiplash thrashing and the black magic and mystic herb invoked in the lyrics.

And so it goes over the course of Warp Riders. Space trucking, vocal-based songs like the title track and “Night City” give way to full-throttle instrumentals like “Astraea’s Dream,” replete with 64th-note runs and pick-squealing savagery, before settling back into thunderous grooves propelled by Cronise and Shutt’s muscle-car riffery and the thumping bass and drums of Bryan Richie and Trivett Wingo.

Nods to Foghat and heavy boogie aren’t the only deviations from metal dogma that set Warp Riders apart. Lead singer Cronise’s rich tenor vocals steer clear of the affectations that define much of contemporary metal. And Cronise and Shutt often opt for a restrained and economical lead style that, while almost anathema to the metal and heavy rock gospels, tip the cap to Thin Lizzy’s Eric Bell and P-Funk’s Eddie Hazel.

On the day I interviewed the affable and articulate Cronise and Shutt, the band were fresh off a video shoot near Death Valley that left a few of the crew hospitalized with heat stroke. It doesn’t get much more heavy—or rock ’n’ roll—than that. And by all rights, the guitarists should have been exhausted. But they were still quite eager to talk about new directions, hidden influences, and why the next record may end up being death metal anyway.

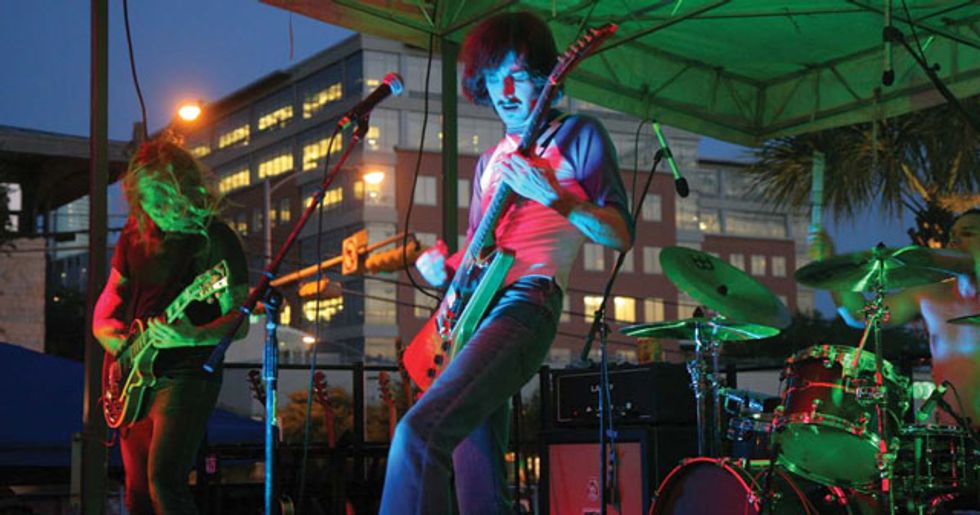

Shutt, Cronise, and Wingo performing live at Waterloo Records and Video in Austin, Texas, August 23, 2010. Shutt is playing a Les Paul Custom, Cronise has his trusty 1979 Gibson Explorer II, and a Laney head driving an Orange 4x12 cab is visible in the background. Photo by John Carrico

Did you make a conscious decision to adhere to a story or make a concept album early in the writing process?

Cronise: Compared to most concept records that I know, it’s really more of a story record. Some concept albums are just about a related subject, in a general way. But this really tells a story.

Shutt: It’s almost a soundtrack to a story or a rock opera, really.

Were you challenged to expand your guitar textures to illuminate or tell the story?

Cronise: I stuck with what I’ve been using— and my Orange amps are a big part of that—but I tried to write rhythm parts that were a little simpler and would come across better in a live situation. But Kyle would play a lot of insane solos to counter that and fill things out.

Shutt: I think my natural growth as a musician and curiosity for wanting to get different sounds took care of that. I started using a Tube Screamer for all my leads and threw in a wah to give them a bit more variation. But I didn’t really feel the need to do that for the story’s sake. If it worked out that way, it’s just a nice coincidence. The lyrics have always been the last thing to come in a Sword song, and in the case of this album, the story that J.D. had in mind became the lyrics, so the music was pretty well formed before it evolved into the Warp Riders story.

How do you work out songs?

Shutt: Usually J.D. and I will just bring riffs to practice. We’re pretty tight at this point, so the song’s skeleton will usually come together in one or two practices and take shape from there. We spend a lot of time playing things over and over again until we get bored with the parts. Then they become new parts and the song evolves that way. The good stuff usually sticks. We keep working it until every little screw is tightened and everything is polished, and then you have a Sword song.

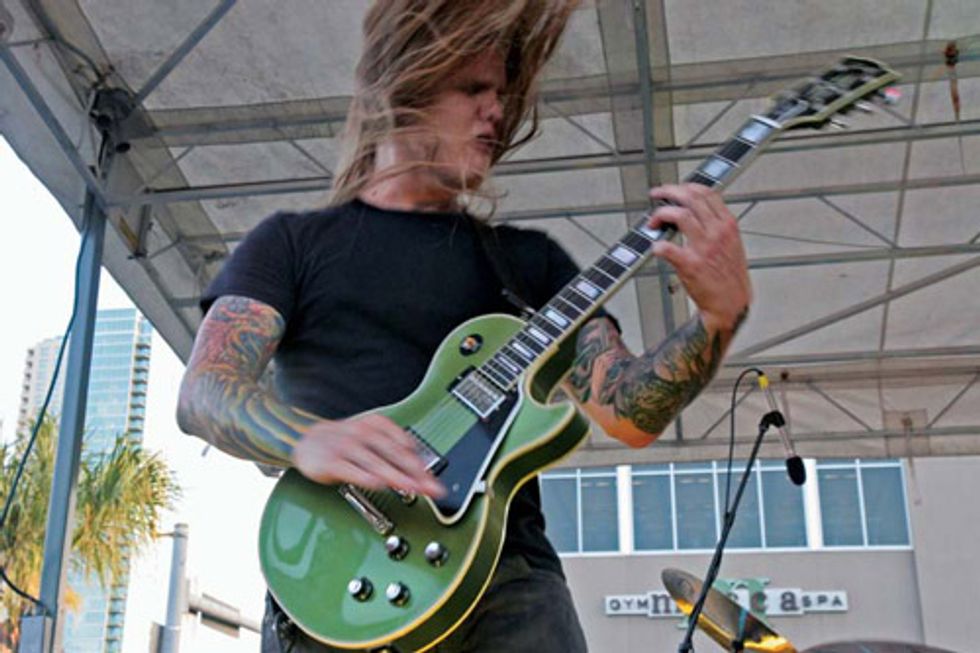

Shutt onstage with his green Paul, August 23, 2010. Photo by John Carrico

Some of the playing is quite economical on this album. Were you trying to create more space for the narrative?

Cronise: Maybe unconsciously. A simpler riff is easier to sing over and get the story over. So yeah, I was writing the songs to be more open. But there are still instrumentals, as well as a lot of aggressive riffs in those instrumental sections where the mood or the story called for something more high energy. I don’t really like to sing in an aggro fashion, so sometimes the instrumentals and the guitar playing have to carry that mood. Plus, sometimes I like to keep my head down and rock. That really was kind of the design—short, fast instrumentals and longer, more involved rock-song structures.

Shutt: When we started the band, I was 20 years old. So a lot of that [economy] is just getting better as a musician, getting more comfortable, and knowing when to go off or lay back. I’m less interested in getting too noodly—and I’ve really started to hate listening to a lot of that stuff anyway.

When it came to composing parts or songs, were you influenced by artists who don’t play heavy rock?

Cronise: Yeah, definitely. You can hear a ZZ Top influence in there. But there’s even some homage to the Meters hidden in there. We listen to all kinds of stuff and it seeps through.

You’re not afraid to upset metal purists and openly declare the influence of a New Orleans funk band. What inspires you to defy expectations?

Cronise: Well, I can’t imagine trying to write a third record that was a continuation of the first two. We’ve done that. The first two records don’t really sound like each other, either. They’re an evolution too. I’m not rejecting metal. Our next record could be all death metal. Who knows? But we tour a lot with bands like Clutch that are just really good hard-rock bands, and we relate to that—an approach to rock that’s really, really heavy, but isn’t quite so aggro.

Shutt: It definitely feels good to just make a great rock record. It had started to feel like I couldn’t remember the last time I’d heard a kick-ass rock album, and that was in the back of my mind all the time. There was a time that bands were good and made good records without worrying what genre they were going to fit into or how they were going to be pigeonholed. The metal community can be pretty brutal—sitting around on message boards and criticizing anything that isn’t metal enough. And you get tired of all that. I don’t understand why something can’t just be heavy and different.

Cronise warps back to the ’70s with a B.C. Rich Mockingbird, a sweatband, and an Orange half-stack, August 23, 2010. Photo by John Carrico

When you recorded this album, what other players were you listening to?

Cronise: I was playing in a ZZ Top cover band over that time, and learning Gibbons’ stuff was a really good education. He’s one of the only players I feel comfortable trying to emulate in any way. Most professional players are beyond my ability, but I really relate to Gibbons—even though I can’t play anywhere near as well as him—and don’t mind trying to steal a few of his moves.

Shutt: I love Kiss and Ace Frehley’s playing. I love Jerry Cantrell. Pete Anderson [of Dwight Yoakam fame] is great. Redd Volkaert is just awesome too. He plays country stuff down in Austin all the time, and he’s just amazing. It’s crazy inspirational to watch that guy play. You just want to play better, you know? And there’s that sense of hearing the guitar in a new way every time you see him—which is huge when you’re just watching heavy players all the time. Watching Redd, you just get a feeling in the gut that you’re seeing a real guitar player. It kicks you in the ass.

So you relate more to feel or emotional players?

Cronise: I absolutely love watching shredders work, players who can make their guitar do anything. But I’m not a precision player, so the studio can be a headache, even when I like the sound I’m getting. Kyle makes up for that a little bit. But I definitely appreciate soul in a guitar player and it’s inspiring to hear where that takes people.

What rigs did you use in the studio?

Shutt: Pretty much the same rig as the last record, with the exception of the Tube Screamer and my wah. I just bought a ’68 reissue Les Paul Custom, which I played for most of my rhythm tracks, and a ’61 reissue SG I used for “Lawless Lands.” It has Rio Grande Barbeque Bucker pickups—the same pickups I have in my Guild S-100. J.D. was using a B.C. Rich Mockingbird with EMGs that I played for a couple of leads.

A lot of your tones are less jagged and metallic on this record.

Cronise: I recorded through two amps simultaneously—I plugged into an Electro- Harmonix Metal Muff distortion and then into an Orange OR80 reissue, and I also used a new Orange OR50 40th Anniversary head, set up a little bit dirty through a separate Orange cab. I used that rig for every track. It was a small victory for me because [producer] Matt Bayles was telling me about all the amps he was going to make me try before we went in, and I was like “Oh, man . . . I’m not sure.” I like my own stuff because I’m really comfortable with it. So I was a bit defensive about that. As soon as we mic’d up my rig and played for a bit, we didn’t move a thing. I didn’t dare say anything, though. As soon as I would have mentioned it—“Hey, we’re using my amp, huh?”—he probably would have tried to talk me into a Soldano or something. But I really like that sound. Those Oranges are definitely my voice.

|

Cronise: Some of those tones are a Hammond organ. But we used a lot of Leslie for guitar as well, which is a sound Matt is really fond of and we liked too.

Shutt: Matt definitely helped us with that one. I’m not sure it would have turned out as well if we’d produced it ourselves. He had the patience to fill that track out and give it some texture. He worked with us that way a lot.

Have your roles changed as guitarists over the years?

Cronise: It’s funny, Kyle used to never play solos at all and I’d play most of them—but he plays 60 to 70 percent of them now. But I don’t miss it. I used to play solos by default, because Kyle was really more into thrashing. But he’s totally come into his own and is a lot more interested in leads. Once he started playing that way, I got really into it, like, “Here, just take that one. And that one. And that one too!” It made things a lot easier for me—especially as I think more in terms of singing.

Did that free you up to develop the more melancholy, melodic side of your sound?

Cronise: Most music needs melody at some point to make it music, I think. And I probably feel that more strongly now. Maybe that’s why you hear more melody and less face pounding.

Shutt: I think that came out of really wanting to hear things like choruses you can sing along to—and thinking more about how a good rock song works.

Did you use any unconventional tunings on Warp Riders?

Cronise: We still tune down to C. But we wrote a lot less in that key, so they sound a little more punchy and as if they were written in standard tuning. Playing in those higher keys is definitely easier for my vocal range too. It means I strain myself a lot less and the live performances are better.

Where do you see heavy music in general going? And where would you like to see it go?

Cronise: I would like to see technology abused less. Bands are making records entirely from samples. That’s cool for some things and it can sound really good, but I think it strips the soul out of rock music. It comes across as really artificial to me. And I think you lose your ability to hear good tones. I’m not a Luddite by any means, but you really need feel to make most music—and certainly heavy rock.

To me, getting up and playing music in front of people is the ultimate. It’s been that way since people were living in caves, and when we’re living in caves again we’re going to want to have that ability [laughs]. It’s good to know how to work outside of technology.

Shutt: I just want to see more good bands. The way things are with the music business— how labels treat bands, how expensive it is to tour—it seems folks are now playing things pretty close to the vest. I don’t see many bands getting the breaks we did just six or seven years ago. Plus, the industry is changing so fast and there’s so much product— good bands just don’t always get a fair shake. And a lot of bands that do get a break get signed because they’ve jumped on some genre. And that comes at the expense of really good bands that just write great songs and rock, even though they’re still out there. I mean, we played with a band called Gentlemans Pistols recently that was just killer. They rock. They have tunes. And, man, they can sing. Everything I wish more bands were doing now!

The Sword's Gearbox

Kyle Shutt

Guitars

’70s Guild S-100 with Rio Grande Barbeque Buckers, Gibson Les Paul Custom ’68 Reissue, Gibson SG ’61 reissue with Rio Grande Barbeque Buckers

Amps

Orange Rockerverb 100, Orange 4x12 cabs

Effects

Ibanez Tube Screamer

J.D. Cronise

Guitars

B.C. Rich Mockingbird with EMG pickups, 1979 Gibson Explorer II

Amps

Orange OR80 Reissue, Orange OR50 40th Anniversary, Orange 4x12 cabs

Effects

Electro-Harmonix Metal Muff

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.