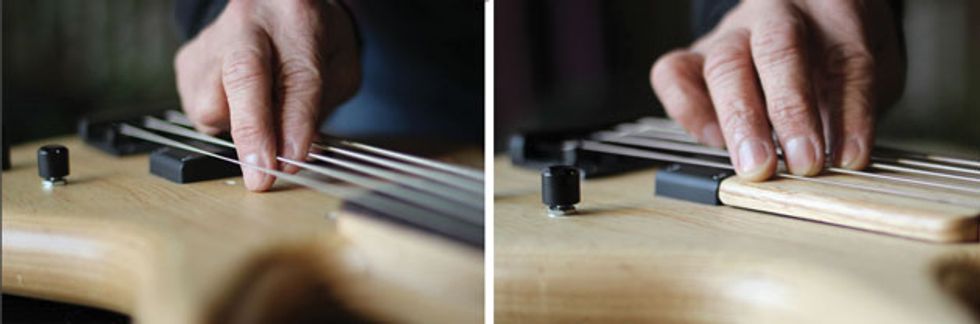

The first electric basses came with several accessories that might look odd to players only familiar with modern instruments. Many had huge covers for the bridge and pickup areas. With these installed, the only possible playing area was close to the neck, where everyone expected us to play while serving the rest of the band with warm, supportive, and discrete low end. Back then nobody considered anything other than finger- or thumb-style playing. There were thumb and finger rests above and below the strings to accommodate either preference.

It didd´t take long for bass players to start removing the covers (though the thumb rests remained in place for some time) and the potential playing area expanded. Nowadays we’re used to playing everywhere from bridge to neck, depending on the desired tone. But unlike the classic thumb rest, the pickup extension underneath the strings can get in our way and influence our playing simply by leaving us less space.

Some players use the pickup as a thumb rest, but tilt their picking hand so as not to play in the limited space above the pickup, while others like to have something under their fingers to keep them from digging too deeply into the strings. Playing directly above a pickup—that is, close to the strings—leaves less room to move your fingers, which can sometimes facilitate faster playing, with improved accuracy and evenness. Without the possibility of playing very hard, you can develop a light, speedy touch.

An adjustable ramp. (From status-graphite.com.)

Whether that’s liberating or limiting depends on your musical needs. But if you get into the habit of resting on the pickup, you may find yourself restricted to only those picking positions. If you like that method, but wish to expand your playing area to the entire range from bridge to neck, consider using a ramp. In most cases, this is a block of wood shaped to fit between your pickups and provide a uniform feel as you shift your picking position toward the neck or bridge.

Gary Willis is probably the most prominent pioneer of ramps. “I suppose I invented that,” he says, “but I’ve heard of other people using it independently of me. It started around 1980 as a solution to protect my fingers from getting cut by the adjustable pole pieces in a pair of pickups mounted side by side. I went back to one pickup on the next bass but added a piece of wood instead.” (Willis’ website, garywillis.com, includes info on building a ramp.)

The ideal ramp provides a seamless area under the strings, level with the pickups and mirroring the fretboard radius so as to maintain uniform distance across all strings. (Since most pickups are flat on top, some basses come with an integrated assembly of ramp and pickups, using one large housing.)

You can get a general sense of whether this playing style is right for you by adjusting the pickups very close to the strings, but that’s not the whole package. The more fingers (or thumb) you tend to use, the more you risk getting stuck. A good ramp will help keep your fingers in place, though only you can judge whether this approach is right for you. Will it promote speedier playing, more efficient movement, and improved tone, as Willis suggests, or instead limit your expression?

Ramps are most often used on fretless basses, because these are generally played more softly than fretted basses. (A string hitting a metallic fret sounds way nicer than one falling flat against a fretless fingerboard, so you often want to soften your touch on fretless.)

An example of a slanted “slap-ramp.” (From status-graphite.com.)

Willis also discusses the change in tone resulting from a lighter touch. He compensates by cranking his amp’s volume, and describes the resulting tone as bigger, with stronger fundamentals, the notes ringing out louder and longer. When you play hard, you loose some of the vibration when the string hits the fretboard. This initial kick is often what makes you get heard in a loud band. Hitting the fretboard produces strong upper harmonics that slowly “wobble out” as the string vibration settles into a sinusoidal waveform. For some players, these frequencies are precisely the quality that differentiates basses from synths. Others bassists—especially jazz players—opt for the enhanced evenness and speed a ramp can provide. Ramps are most often mounted using double-sided tape, so installation is simple and reversible.

While we’re on the subject of ramps: Ever heard of the far less popular slap-ramp? The name is a bit misleading, since they’re not intended to aid slapping so much as the complementary popping of high strings. They are mounted directly at the end of the fretboard, reducing the distance between string and body as desired. (Presumably, close enough for your fingers not to get stuck, but far enough to get hold of the string.) Some are even slanted to allow different techniques by altering positions. It can also be the tool that helps you nail that Victor Wooten-style double-thumping.

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Shop Scott's Rig

Shop Scott's Rig