Intermediate

Intermediate

- Create depth by breaking up chords.

- Learn to experiment with rhythmic shifts.

- Add melody notes to animate chordal lines.

For well over 50 years, Bob Weir has been mystifying and delighting fans around the globe with seemingly endless musical ideas, helping to define the sound of the Grateful Dead. Weir has always taken a truly individual approach to rhythm guitar, centered around his affinity for melodic accompaniment. More than just strumming rhythmic patterns, he creates melodies that surround a given chord, adding texture and harmonic depth to the music. The following are examples of the way Weir adds color and rhythmic variety in harmonic patterns and illustrate his artistry as an improviser.

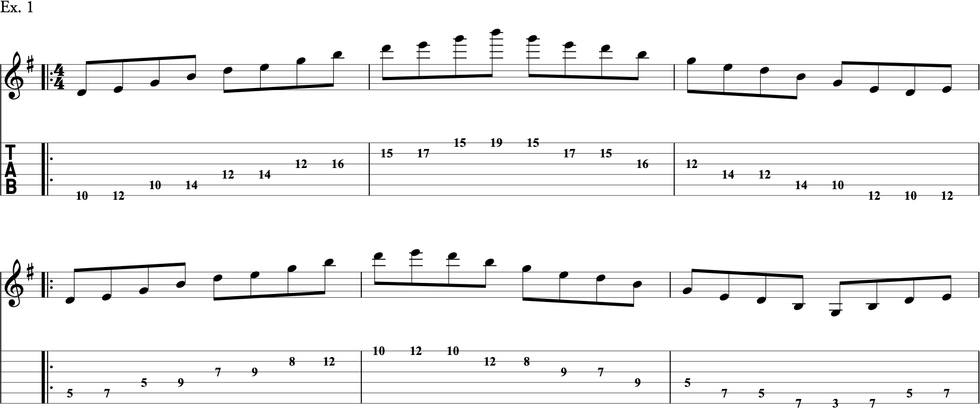

Ex. 1

Ex. 1 shows a contrast in rhythmic activity, where the first two measures are much busier compared to measures three and four. Harmonically, notice the suspended 4th that resolves and leads to the next chord in measure two. Measure two highlights a wide interval of a major 6th and also the 9th, adding color to the triad. Also, in harmonic contrast to the first two measures, measure three and four end the phrase with 3rd-less triads. This is a good example of a compositional quality in Weir’s playing.

Ex. 2

Triadic playing is certainly a component of Weir’s improvisational playing. In Ex. 2, you can see how he breaks up triads by articulating single notes and double-stops with the chord shape. You can see the three D chord shapes in measures one and two starting with a power chord and then sliding into the 3rd (F#) and the next chord shape, grabbing the 1st inversion D triad followed by a root position version of the same chord. Also notable, the use of long and short rhythms adds very musical syncopation. In measure five, note the F#m played completely, then breaking it up with the root followed by double-stop 3rd and 5th of the chord. The next chord, G, is arpeggiated, again in short and long rhythm. That rhythmic idea continues in the last two measures.

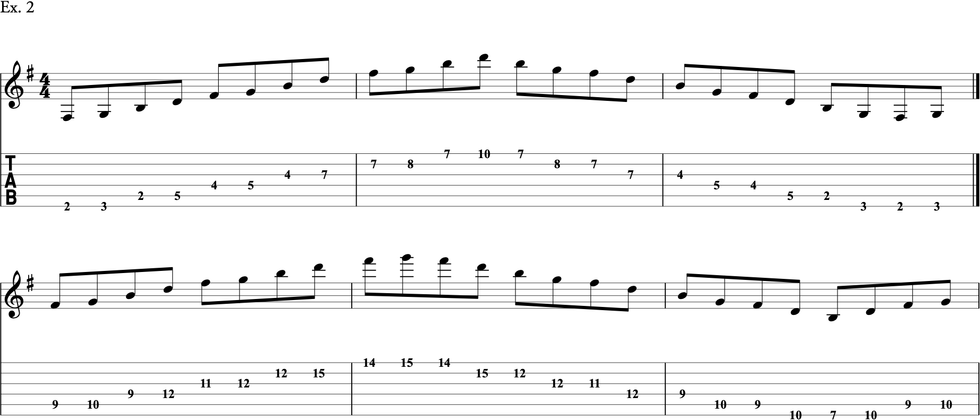

Ex. 3

Ex. 3 is another example of breaking up triads, but at a faster tempo. Notice the open E string doubling the 5th of the chord. That’s a nice touch and can be used on other chords as well, adding or doubling any chord tone. In measure three, the A/E chord held for two-and-a-half beats helps to break up the two-beat feel, as does the D/F# in measure four.

Ex. 4

The Dm sequence in Ex. 4 illustrates a Weir-like approach to melodic accompaniment and also a reference to the relative major, F. Beat 3 of measure one and beat 1 of measure two can be seen as using the relative F major, outlined in the diagram in parentheses. Notice the Dm and D5 played in a broken fashion followed by color notes on beat 3 of measure three, sliding double-stops down from D and F to C and E, the 7th and 9th of the Dm chord. The phrase resolves with descending Dm groupings, and a double-stop on the upbeat of 2 that could be thought of as C5, C/D or the 7th and 11th of Dm. Either way, you’re adding color and dimension to static harmony.

Ex. 5

Bending a string within a double-stop is pretty common in Weir’s playing, and you see this in Ex. 5 on beat 4 of measure one. The D# is pre-bent up a half-step to E and released in time down to D#, then pulled off to C#, all while holding on to the G# on the 3rd string. Rhythmic and melodic themes are apparent in Weir’s playing. In measures three and four, you can see variations of a rhythmic idea from measures two. All three measures have a version of a dotted quarter and eighth note rhythm, but end in a slightly different way.