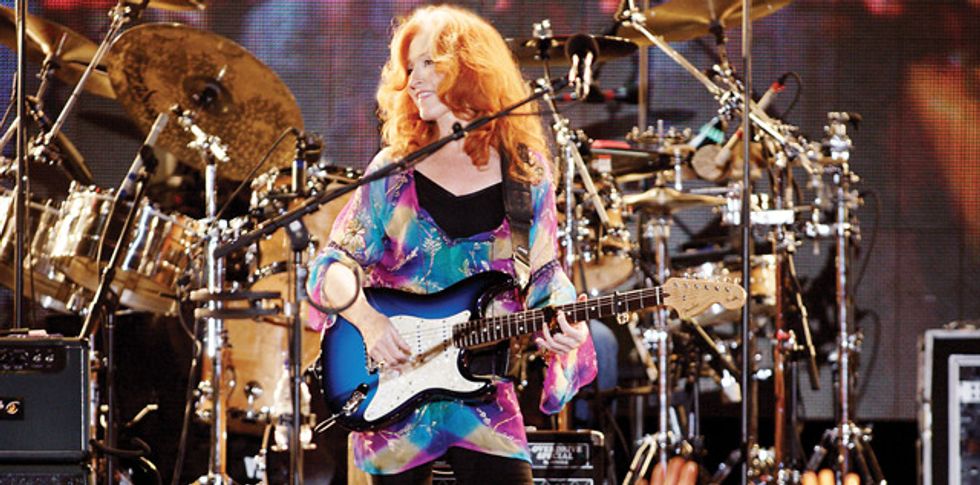

Bonnie Raitt bought her famous “Brownie” Strat for $120 in 1969 and has played it at every gig since. Photo by Buzz Person

While teaching herself to play acoustic guitar as a teenager in the late ’60s, Bonnie Raitt—now world-renowned for her sultry voice and bracing electric slide prowess— dreamt of leaving her native California and joining the Greenwich Village beatnik scene. As soon as she was old enough, she left her parents—Broadway star John Raitt and pianist Marjorie Haydock—behind to head east and plant her musical roots in the burgeoning folk activist movement.

From there, Raitt tapped into a wide array of influences, with a big turning point coming when she befriended influential blues promoter Dick Waterman while she was in college. Waterman gave her the opportunity to share stages with blues gods like Howlin’ Wolf and Mississippi Fred McDowell, which no doubt left an indelible impression on the blossoming slide player.

Despite such beginnings, Raitt’s road to superstardom was anything but easy. While a 1970 gig with McDowell led to a record deal with Warner Bros., she experienced only moderate commercial success with the label. Her first hit didn’t come until 1977’s “Runaway,” and she was eventually dropped in 1983. She struggled with addiction until Stevie Ray Vaughan’s own recovery in the mid-’80s prompted her to get clean. Not long afterward, Raitt released the album that changed everything. Released in1989, Nick of Time won her three of her nine Grammys to date and set her on a path toward her 2000 induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. In the process, Raitt went on to become the first woman to have a signature Fender—an offer she originally turned down because she was uneasy about putting her name on a product. (Ever the activist, Raitt used the profits to create the Bonnie Raitt Guitar Project, providing guitars to underprivileged kids in more than 200 Boys & Girls Clubs of America.)

Slipstream, out this month on Raitt’s new Redwing Records label, is her first album in seven years—although she’s been far from dormant in the interim. Much of that time was spent on the road, including on a stint with Taj Mahal before her brother was diagnosed with a second brain tumor. She took care of him until his passing, and soon afterward one of her good friends passed away, prompting Raitt to take time off for the first time in more than a decade.

The incessant road warrior’s hiatus lasted only a year before things started pulling her back toward her creative muse. She ended up in the studio much sooner than originally planned after meeting with producer Joe Henry to see if their styles blended. What was originally supposed to be a couple-song jam turned into an entire album. “Halfway through the first song,” Raitt recalls, “we knew we had something very magical.”

Raitt says she can’t put into words exactly how she knows when a song is right, but she recently told Premier Guitar her approach always seems to have a way of illuminating her life. She also shared why the guitar is her vehicle of choice, how newer artists like Bon Iver inspire her as much as Muddy Waters and John Lee Hooker, and what her advice is for guitarists trying to find their voice.

You picked up your first guitar—a Stella

acoustic—at age 8. What made you stick

with it?

I grew up in a very musical household, with

my mom playing piano all the time for my

dad’s rehearsals. So there was a role model

for me, with my dad singing these great

Broadway scores. Him being a Broadway

star was a great gift for us to be able to see

what that world was like. And the message

of playing music and getting paid for it—

doing something that you not only love,

but that doesn’t even seem like work—was

not lost on me. I must’ve tucked it away

and then remembered it when the opportunity

came years and years later to play

music for a gig.

You’ve said before that electric guitar

burns inside of you. What still turns you

on about the instrument?

It really sounds like a human voice. The

electric guitar will sustain a note, especially

a single note, much longer than an acoustic

will. And then when you play slide—which

is so much like a human voice—you can

work the amplifier and the overdrive. Now

I use a compressor when I play slide, and

with that you can sustain a note as long

as your emotions will hold. It’s like surfing—

you can ride that wave of emotional

intensity and taper it off and build it

up, depending on how you work your

volume knob. It’s really an exciting way

to express yourself. So electric guitar, for

me, has the raunch and the beauty that

more openly reflects the range of emotions

I want to get when I’m singing and

playing. It’s much more expressive to me.

And that’s what keeps me going back.

The solos on your new rendition

of the Dylan tune “Standing in the

Doorway” have that same lyrical quality—

they sound like someone crying.

Yeah, and then to have pedal steel behind

me. I rarely get to do that. Greg Leisz is

one of my heroes, and to be playing with

Bill Frisell and those guys was such an

honor. One of the great things about slide

guitar is that I found I could go to Cuba

and play with musicians there, and then I

went to Mali, Africa, where the blues was

born, and within a day I was playing with

those musicians—because it doesn’t matter

whether you know all the chords if you

know your way around with a slide. It’s

such a monophonic instrument: You can

sit in with the Chieftains on slide as well

as you can Cuban and African music.

When your own lungs literally run out of

air, you can take the slide guitar and add

that other voice.

You cut three tracks with Frisell.

Did you have him in mind originally

or was that something you and Joe

Henry [who produced four Slipstream

songs] decided together?

Joe first suggested we work with Bill.

When we were getting to know each

other on the phone, we were talking

about mutual friends and people we love,

and I was complimenting him on his

Scar record. I love Bill’s playing on that,

so he said maybe we should get Bill in

on the sessions.

Slipstream is your first release in seven

years, and around 2009 you decided

to take some time off. What was that

like for you after working for so many

years straight?

We did a two-year tour after [2005’s]

Souls Alike, and then a year before the Taj

Mahal tour my brother was diagnosed

with a second brain tumor and I took a

break to care for him. I hadn’t really had

a break since my parents passed away. In

10 years, I had been on the road or recording

pretty nonstop or going through my

brother’s terrible illness and passing, so I

needed to take a break and step back. In the

past, “taking a break” really meant writing

songs and looking for new material. But I

had been doing that basically since 1970

without a real break. Sometimes you need

to clear the deck and let the field go fallow

and not think every time you’re playing a

song, “Is this something I want to record?”

Sometimes you just have to live.

Yeah! I got to listen to other kinds of music.

I went to a lot of shows and didn’t sit in—

didn’t even tell [the performers] I was there. I

love doing yoga, and I love hiking and biking.

For somebody who’s on the road all the time,

just being home is really the vacation you

want to have. So I got to balance some of the

other aspects of my life and be with my family

and friends and really enjoy some time at

home, watching what fours seasons look like

changing in a row from the same place.

How did you know you were ready to go

back into the studio?

After a year at home, little sprouts poked their

head up. I was listening to songs when I called

Joe about working together. This was months

earlier than I was expecting to go back in the

studio, but those sessions were so exciting that

it really jumpstarted the record for me.

So you got the itch?

At a certain point, you just want to go back

and do the other thing—you don’t want to

do anything too much. I don’t know if you

have members of your family or have known

people whose mom or dad retire or got laid

off after many years of going to the job, and

they don’t know what to do with themselves.

It’s not the music part I was tired of—it’s the

promotion, clothes, sets, tours, interviews,

marketing, and monitoring the distribution.

All the business of being in this business is

what gets wearing, not the music. But without

all that, you can’t go on tour.

How did you go about determining

which songs to put on this album?

It’s pretty much the same as it’s been since

my first album: I listen to a lot of different

song ideas that I’ve written, and the ones I

like I put in this pile. Ninety-nine percent

of the stuff I listen to isn’t right, but I know

when I have to do a song. I’ve already said a

lot of stuff in previous records, and you don’t

want to repeat yourself musically or lyrically.

I don’t plot it—I don’t conceptualize it—I

just let the music speak to me, and when I

have a enough songs that I think are going

to go well together, then I go into the studio.

What makes a song one you have to do?

It’s hard to put into words. It just has to

speak to me personally. I mean, I’m probably

not going to cut polkas or disco or speed

metal [laughs], but other than that I don’t

have any limitations on the kind of music it

can be. I mean I like listening to that stuff,

but it doesn’t mean I’m going to do it. There

are definitely veins of styles that I stay in. I

just let that mysterious process wash over me

than rather than try to analyze it.

What are your favorite slide tunings?

I play in open A [E–A–E–A–C#–E, low

to high], or I go down to G [D–G–D–G–

B–D, low to high], which is the same but

everything is one whole note lower. The reason

I use so many guitars onstage is because

songs are in different keys—open D, open E,

open E%—and it saves time between songs.

Sometimes I use capos, too—if I’m singing

in C, I’ll put the capo on the third fret.

Which guitars are you going to tour with

this time around?

I’ve got a really great collection. My brown

Strat—the body is a ’65 and the neck is

from some time after that. It’s kind of a

hybrid that I got for $120 at 3 o’ clock in

the morning in 1969. It’s the one without

the paint, and I’ve used that for every gig

since 1969. I also have two or three of

my signature Fenders. Those guitars are a

metallic blue to indigo, and they have Texas

Specials pickups—which are really great—

and jumbo frets like my other Strats. Then

I have a ’63 sunburst Strat that used to be

owned by Robin Trower. I have Seymour

Duncan pickups in that.

You also use a Gibson, right?

Yes, I have an old Gibson ES-175 cutaway. I

went to the cutaway because I use a capo on

the third and fifth frets, and I can’t get the

octave unless I have a cutaway. That’s part of

the reason I went to electric, as well. Partly

for sustain and partly to be able to get the

octave when I have a capo on.

What do you like, sonically, about bottleneck

slides over other slide types?

I didn’t know any different! I literally

soaked the label off a Coricidin bottle

until I got to college and saw people playing

other types. I’ve never used anything

but glass. Jim Dunlop makes them for

me. My fingerpicks have to be custom

made, too, because they stopped making

small plastic fingerpicks years ago—they

only make metal fingerpicks now. Metal

fingerpicks are for the banjo and it’s a different

sound. I’m sure people use them

on guitar, but plastic sounds better for

what I do.

You’ve been an inspiration to younger

generations of singer/songwriters, from

the Dixie Chicks to Adele and Bon

Iver, whom you recently saw live, right?

Yes, I went to meet Justin [Vernon, Bon

Iver frontman] finally after talking to him

on the phone. His show was incredible.

Go on YouTube and type in “Bon Iver live

show 2011” and check it out. He blew

me away on record, and I didn’t think he

could duplicate it live, but he did it.

What else is inspiring you these days?

One of the most amazing talents is Sarah

Siskind. Then there’s my friend Maia

Sharp, who was an opening act on my last

tour. She sings on Slipstream, and I cut

three of her songs on Souls Alike. Also, my

friend Marc Cohn. Jackson Browne and

Bruce Hornsby are like brothers to me. I

love Bruce’s latest double-live album, Bride

of the Noisemakers. If I had to be on a desert

island and could only have one artist’s

music, it would be Bruce Hornsby. Mavis

Staples is one of my heroes, too, so she and

I are going to do a lot of shows together.

Are there any players you haven’t

played with yet that you’d like to?

Justin Vernon from Bon Iver. I’d love to

play with the Stones and Keith. I opened

for them on my last tour and sang “Shine

a Light” with them, and I’m on their

DVD. I’d love to do more recording with

Bill Frisell. I love classic jazz. There are

two jazz singers—Lizz Wright and Melody

Gardot—who are doing incredible work.

I would love to make an old 1920s bluesjazz

record—not like an old Chicago jazz

band, but just really, really beautiful piano

jazz. So, one day …[laughs].

On that note, what were you dreaming

for the future during your hiatus?

What are you looking forward to down

the line?

The whole Occupy movement has given me

some hope that, across party lines, newer

generations will rise up and ask for accountability

and transparency and reform some of

these laws. That is my first dream—to see

people become more awake and compassionate.

My dream is to be a service in that

struggle and to not get discouraged. One

of the great things about playing live—besides

being fun—is that we can buoy the troops, in

terms of raising money and awareness for these

issues. I want to enlist more artists to be politically

active to make a difference. It’s that marriage

of music and being of service. My heroes

are of the “The Times They Are a-Changin’”

period—like Bob Dylan.

Bonnie Raitt's Gear

Guitars

“Brownie” Strat with 1965 body (tuned to open

A), three Fender Bonnie Raitt signature Strat

prototypes (one in open G, one in open A%, and

one in standard), Gibson ES-175 with a P-90,

three Guild acoustics (one with higher action for

slide work, another in open C), purple Pogreba

Guitars resonator

Amps

Bad Cat Black Cat 30R 1x12 combo (Raitt uses

only the EF86-driven channel 2)

Effects

Boss CS-2 Compression Sustainer, Pro Co Rat

String, Picks, and Accessories

GHS Boomers custom electric sets (.013, .017,

.020w, .032, .042, .052), GHS Phosphor-Bronze

acoustic sets (.012, .016, .020, .036, .046, .056),

custom Jim Dunlop molded-plastic fingerpicks,

Dunlop bottleneck slides

It’s really come full circle for me to be able to record his tunes again, even if they’re not overtly political. Anytime we talk about human beings and the way they treat each other—it can be a man and a woman, or a father and son, or two countries—there has to be the same respect. You have to listen—it’s the same core issue. You’ve got to find that light in the other person and appeal to it. That’s one of the things that music is really great for.

You were an apprentice to some of the

greatest musicians of all time, and now

you’re in the same category as those you

looked up to. What advice do you have for

players trying to find their voice?

I think it’s really great to get good at your instrument

and your craft. There’s no substitute for that—even

the most talented and lucky person still has to put the

time in. Get to the point where you can hear yourself

on tape and go, “That’s pretty good!” If your heart

and soul are in it and you’re doing it for the right

reasons, nothing can hold you back. Take opportunities

to get your music out there and heard, even if

it’s a small group of people at first. Find satisfaction

in pleasing yourself first, and then those you respect.

Whether you’ll make it in this crazy business, I don’t

know—that’s to be seen. But if you believe in it, keep

working at it. Post it on YouTube. It seems obvious,

but those opportunities weren’t around when I started

out. I’ve got a very talented nephew who’s writing

music, and he’s been doing it with his laptop. Pro

Tools has made things so incredible! You can get good

in a short period of time if you at least put time into

it—and a lot of heart.

Youtube It

Get a glimpse of Raitt’s mesmerizing, blues-infused picking power

in these videos ranging from 1976 to 2005.

John Lee Hooker and his protégé work up such a sweat that Raitt says, “Somebody

better get this man a towel” during this performance for Hooker’s John Lee Hooker &

Friends 1984-92 DVD.

A young, charismatic Raitt wields the double-threat of a velvety voice and a thicksounding

ES-175 with uncanny soulfulness.

Raitt calls fellow blues crusader Keb’ Mo’ “funky as hell” as they trade flirty, smokin’

licks at the Trump Taj Mahal Casino in Atlantic City, New Jersey, in 2005.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)