Can’t Get Enough is the debut album by the Rides, a new band fronted by guitarists Stephen Stills and Kenny Wayne Shepherd. But in a sense, the project originated in 1968, nearly a decade before Shepherd was born.

The spring of that year, Stills found himself at a career crossroads. Buffalo Springfield, the band he co-fronted with Neil Young, was on the verge of breaking up, and he had yet to connect with former Hollies member Graham Nash and ex-Byrd David Crosby to form Crosby, Stills & Nash. He received a phone call from producer Al Kooper, inviting him to contribute to what would became the Super Session album. Kooper had commenced the record with Chicago blues guitar phenom Mike Bloomfield, but Bloomfield jumped ship.

“So Al called me up,” remembers Stills. “I asked him, ‘How far down the list of guitar players am I?’ He goes, ‘You’re right up there at the top!’ And I go, ‘Yeah, right. Nobody knows I’m a lead player—everyone thinks that I’m just a folk singer.” But Stills agreed to replace Bloomfield for the album’s second side. Super Session was a hit, with critics lauding both Bloomfield’s blues stylings and Stills’ West Coast sound.

Fast-forward 40-some years, when Stills’ manager, Elliot Roberts, and record exec Bill Bentley hatched the idea of revisiting the Super Session concept using Stills, plus another guitarist to take the role of Bloomfield, who died of a drug overdose in 1981.

Stills says he was thrilled when Roberts floated the idea, because he’d been looking for a vehicle to play blues, his first musical love. “I started out on guitar playing to Jimmy Reed records. Not Joan Baez, not Pete Seeger—Jimmy Reed, Little Walter, and Robert Johnson. It’s a part of my soul. It’s in my DNA.”

They quickly recruited former Electric Flag keyboardist Barry Goldberg, who played on the Bloomfield side of the original Super Sessions. (Al Kooper isn’t part of the new project.) But they had the seemingly insurmountable task of filling Mike Bloomfield’s shoes. Goldberg suggested Kenny Wayne Shepherd.

“The funny part,” says Stills, “is that I’ve known Kenny Wayne for about a decade from going to [Indianapolis] Colts games. Kenny was always a very polite, gunslinger-type guitar player in the jam bands we’d form for Colts parties. To me he was just ‘Kenny the young guitar player.’ I had no idea of his talent.”

“They called me up and asked if I was interested,” recalls Shepherd. “I said, ‘Yeah, sure!’”

Taking over for an iconic player such as Bloomfield’s might give some guitarists pause, but Shepherd says the thought never crossed his mind. “I don't think there’s going to be all that much comparison,” he says. “We do share a few things in common, aside from appearing on an album with Stephen Stills and Barry Goldberg. For a long time he was successful playing guitar and not really singing. Really, though, our styles are pretty different. He was known for playing a really awesome ’59 Les Paul burst, and I’m a Strat guy.”

Once the trio started playing, the initial concept evolved. “They wanted to throw us into the studio, have us jam for a few days, hit the record button, and see what happened,” says Shepherd. “But once we met up at Stephen’s house to start throwing out ideas, we decided that we wanted to write together. Once that happened, the scope of the project changed.”

It only took a week for the Rides to complete Can’t Get Enough. “We worked the way they describe the Beatles working when they first started,” says Stephen Stills. “It was very organic and natural, which is the way it’s supposed to be done. No machines. No polling numbers. No demographics.”

Goldberg and Stills had already written several songs. “The first time I showed up, they played them for me, and we finished them together,” says Shepherd. “Then I threw out some ideas I had, and we collectively banged out the lyrics. You can’t fake chemistry, especially in songwriting. We didn’t really know how that process would go, but it was actually pretty effortless.”

That creative connection is especially evident in the interplay between the two guitarists. “Most of the time we just intuitively played what we heard,” says Shepherd. “It didn’t require a whole lot of conversation. We all set up in the same room like a live band, so when it came to solos, it was just like a bunch of guys jamming. It wasn’t really mapped out—we just did what felt right, or what the music dictated.”

Stephen Stills and Kenny Wayne Shepherd both attest to an effortless instinctual chemistry

that happens when they play guitar together.

“It was instinct,” agrees Stills. “We treated it like you’re supposed to: with a lot of mutual respect. I learned a lot from Kenny that week, and my sound has changed a little bit. Kenny Wayne Shepherd is the nicest, most gracious and considerate musician I’ve ever met. He’s the antithesis of the sociopaths we usually run into.”

Meanwhile, Shepherd says he treasured the opportunity to study a masterful songwriter/guitarist at work: “I’ve always been very conscious of how vocals and guitar play off one another. Stephen puts a tremendous amount of emphasis on the vocal—sometimes it takes priority over the guitar. That approach has given me perspective on my rhythm playing. For instance, on ‘Only Tear Drops Fall,’ what I initially played didn’t really sound right to his ear, which made me rethink my approach.”

“My approach to the guitar is to pick it up and play where it fits and little else,” says Stills. “Leave some space for the vocal.”

“Stephen is a great player,” Shepherd continues. “He’s been rated one of the top 100 players of all time many times, and I can’t argue with that. We have completely different styles, but when they come together it’s very intriguing.”

Kenny Wayne Shepherd's Gear

Guitars

-Kenny Wayne Shepherd Signature Series Fender Stratocaster

-1958 Fender Stratocaster

-1959 Fender Stratocaster

-1961 Fender Stratocaster

-Gibson Les Paul Custom

Amps

-1958 Fender Bassman

-1964 Fender Blackface Vibroverb

-Dumble ’65 Fender Bandmaster Head converted to an Ultra Phonix

-Dumble-customized Fender Deluxe (“Tweedle-Dee”)

-Dumble-customized Fender Bassman (“Slidewinder”)

-Dumble-customized 1964 blackface Fender Vibroverb

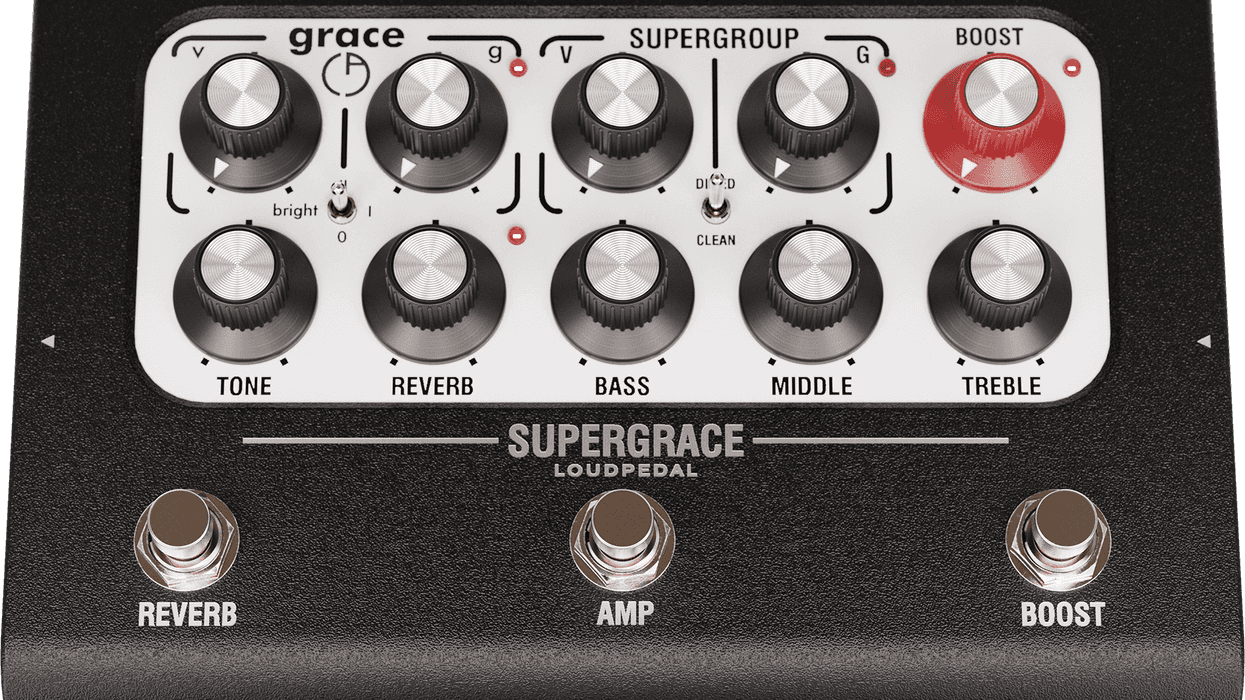

Effects

-Analog Man King of Tone

-Ibanez TS808HW

-Vintage Ibanez TS808

-Jam TubeDreamer

-Jam Delay Llama

-1960s Vintage Fuzz Face

-Dunlop Jimi Hendrix Fuzz Face

Guitars

-Two 1954 Fender Stratocasters

-Pre-War Martin acoustics

-1958 Gretsch White Falcon

-1959 Gretsch Chet Atkins Country Gentlemen

-1958 Gibson Flying V

Amps

-Fender Tweed Bassman

-Fender Tweed Twin Reverb

-Fender Tweed Deluxe

-Marshall 100-watt head

Like the original Super Session, Can’t Get Enough boasts an interesting selection of cover tunes. The new disc includes fresh takes on Muddy Waters’ “Honey Bee” and Neil Young’s “Rockin’ in the Free World.” “I love ‘Rockin’ in the Free World,’” says Stills. “Every time we would play it I’d think of the little nuances that I would add to it. When we finally got to it, I just slammed the shit out of it.”

Another interesting choice was a new take on “Word Game,” which Stills wrote during his Buffalo Springfield days and included on 1971’s Stephen Stills 2. “It was a bit of a throwaway when I did it back in the ’70s,” he says. “But we got it down really cool this time, and it’s just as timely today as it was then.”

One track likely to raise eyebrows is the group’s take on the Stooges’ proto-punk anthem “Search and Destroy.” “That was not a very predictable song for us to do,” laughs Shepherd. “At first [producer] Jerry [Harrison] and Stephen were a little suspicious. But the great thing about this project is there are no egos. We all value and respect each other’s opinions, so when I said ‘let’s give it a try,’ we laid the song down. Everyone was happy with the end result, and we’re all excited that it made the record. I think it piques people’s curiosity.”

Harrison and the band kept things moving quickly, finishing the album in just seven days. “We worked the way they describe the Beatles working when they first started,” says Stills. “It was very organic and natural, which is the way it’s supposed to be done. No machines. No polling numbers. No demographics.”

The recording approach was fittingly old school. “We recorded on two-inch tape and a Neve console,” says Shepherd. “The whole concept was to do it the way albums used to be done, and was an essential element to that sound, though it really puts pressure on the musicians to get it right the first time.”

The Rides debut, Can’t Get Enough, was inspired by Super Session, a 1968 blues album that featured Stephen Stills and Mike Bloomfield on guitar.

Stills says it more strongly: “I’m making records for 180-gram vinyl. I’m not making records for the bullshit iTunes, file stealing, [Napster founder] Sean Parker end of the music business. I agree with Neil [Young] that people are being cheated.”

The guitarists performed on an array of vintage axes, mostly Fenders. Like Shepherd, Stills is a Strat man. “Kenny Ray’s muse is Stevie Ray Vaughan as much as mine is Jimi Hendrix,” he notes. “Hendrix brought me to the Stratocaster in the ’70s. It didn’t become obvious that that was the voice I could get out of it until I figured out what mics and amps to use. I still have my old Buffalo Springfield black Gibson Les Paul, but it’s so heavy that after five or six shows I have to go to the chiropractor. The Strat is lighter, and I’ve found a way to get it to make noises I like.”

Shepherd played a trio of late-’50s and early-’60s Strats, while Stills relied on two from 1954. “I like them because I can play them,” says Stills. “I like the older, thinner frets shaved down, rather than the big, fat Gibson type frets that you dig into. You get a lot of the sound by digging in with your left hand.”

They also assembled an amazing collection of vintage amps. “All my amps are Fender tweeds, and they’re so old, they have hair growing on them,” Stills deadpans. “I’ve had roadies who wanted to cover them in varnish, but that ruins the sound. It’s great old pieces of pine. Not plywood, not fiberboard—pine. The speaker moves the whole box. I’ve got a Bassman, a Deluxe, and a Twin, and I use a combination of the three.”

Shepherd’s amplifiers included a tweed ’58 Fender Bassman, a blackface ’64 Fender Vibroverb, and several amps modded by amp guru Howard Dumble. “I brought in all the amps that Dumble has built for me,” says Shepherd. “I had a ’65 Fender Bandmaster head he converted to an Ultra Phonix, a’57 tweed Deluxe that he calls the Tweedle-Dee Deluxe, and a Bassman reissue that he basically gutted and replaced with his own handwired circuit. He calls it the Slidewinder.”

For the band’s upcoming tour, though, Stills says he plans to bring a very special non-Fender amp: “I’m breaking out an old Marshall 100-watt head. Jimi Hendrix and I both picked out about five each. I have three of them left. I think two grew feet over the years thanks to various roadies who thought, ‘He’s got so much shit, he’ll never miss them.’”

While Stills and Shepherd have built busy solo careers, neither considers the Rides a mere side project. “We’ve already begun writing for the next record,” Shepherd confides. “We all feel confident that this will continue moving forward. I hope we get into the studio at the end of this year or the beginning of next. We’ve all made it clear to one another that this is a priority and not a one-off vanity project. This is something we all want to see through to the finish.”

“I’ve had a great time working with Kenny Wayne,” adds Stills. “We’ll probably write three more songs in the rehearsals for the tour. It’s so much fun. It’s easy. It’s fast—it never takes more than three takes. It’s just bare-bones, old-school, two-inch-tape rock ’n’ roll.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)