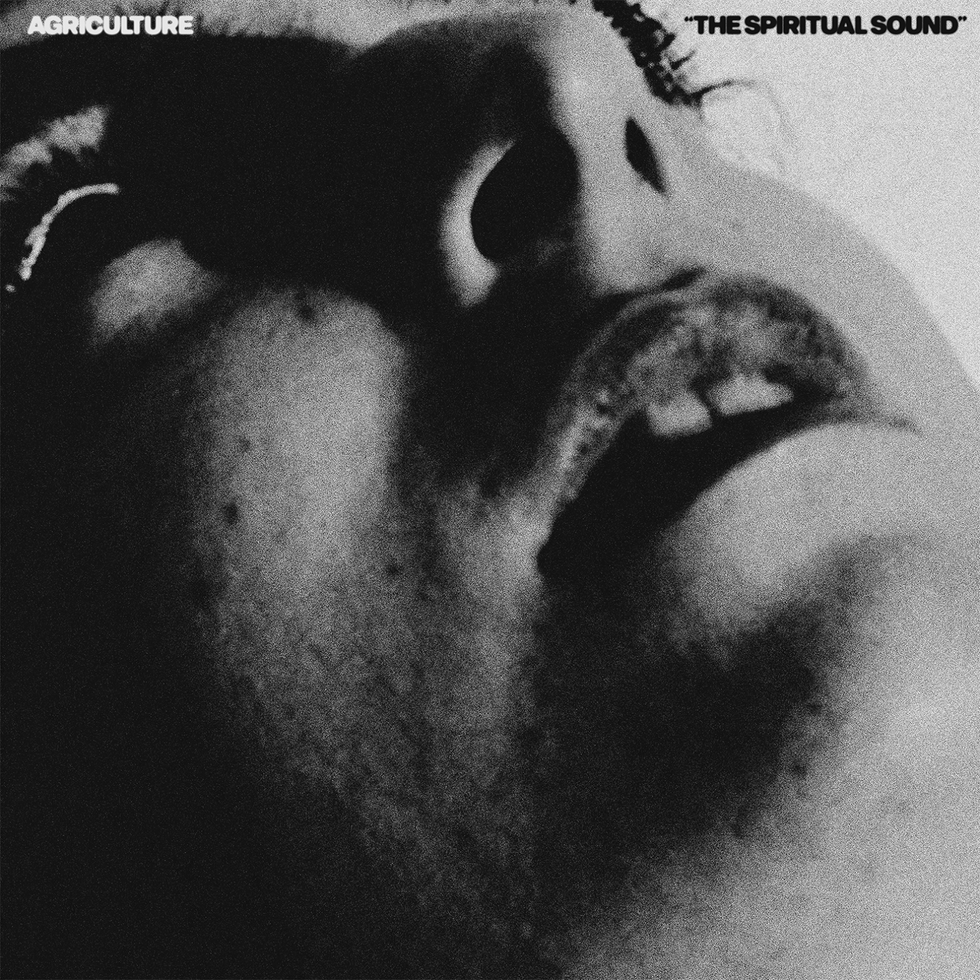

Los Angeles experimental metal band Agriculture’s new record, The Spiritual Sound, might not make sense to you at first listen. When the band sent the album to their friends, many of them were overwhelmed, if not weirded out. The band members weren’t surprised. “If I heard this record for the first time, I’d be pretty confused by it,” says guitarist and vocalist Dan Meyer.

The record opens with clanking bass strokes before a dizzying hornet’s nest of guitars and drums careens around maniacally for 20 seconds. After that, a brutal downtuned riff kicks in, accompanied by face-melting shredding. By the time the song hits the one-minute mark, and vocalist/bassist Leah B. Levinson’s dungeon-creature scream rips across the track, there have been three distinct movements. There are four more minutes, and a few more movements, to go—including a beautiful melodic reprieve that’s reprised near the song’s final moments.

It’s a thrilling shot across the bow from one of heavy music’s most fearless acts. By the end of The Spiritual Sound, Agriculture have extended their tongue-in-cheek genre designation of “ecstatic black metal” into regions like powerviolence, noise, alternative, shoegaze, and sounds that touch on folk and traditional. “Dan’s Love Song,” for example, with its nostalgic melody and simple chord progressions, could be a noise-rock interpretation of some obscure 1800s ballad. (The band lists Metallica, Slipknot, the Jesus and Mary Chain, and Bob Dylan as primary influences on the new album.) “Bodhidharma,” meanwhile, flips on its heel between headbanging metal and passages of silence, punctuated by screams, whispers, and Haug’s frozen, hulking snare and kick bursts. It also features some of Chowenhill’s most mindboggling lead guitar passages.

“The problem that I was trying to solve with my songwriting on this record was, ‘How do I write about things as they occur in my life without overly dramatizing them?’” —Leah B. Levinson

Formed in the early days of the pandemic, Agriculture—Levinson, Meyer, guitarist Richard Chowenhill, and drummer Kern Haug—have defined their sound as something that is once experimental, abrasive, and jubilant. The record title and the band’s self-determined genre designation hail from a jokey remark lobbed at them: “I love the spiritual sound of this ecstatic black metal.” The phrase, and the band, are the subject of debate on various heavy-music forums. There is a certain sense of Ursula K. Le Guin’s world-building at play in Agriculture’s music—a playfulness, curiosity, and seeming inhabitance of an alternate reality.

The Spiritual Sound, Agriculture’s fourth release since forming in the pandemic, finds them once again exploring the extremes of musical sound—both heavy and gentle.

The band’s writing process for The Spiritual Sound was “unusually collaborative,” says Meyer. Songs were brought in fully formed, then torn apart and reconstituted, often with different parts. Meyer likens it to building a character at the outset of a role-playing game. “The head of this song ends up going with the body of that song,” he quips.

Once songs were solidified, they were taken to what the band calls “Richard’s kingdom”—the affectionate term for Chowenhill’s studio, where deep production began after principle tracking. That’s where vocals, overdubs, and “ear candy” were added. It’s also where plenty of sparring took place. “It is a more adventurous record,” says Levinson. “We make a lot of capital-C choices on it, and it really did require us setting aside creative differences, or at least sitting with things and being like, ‘I don’t know where this is going, I don’t like this, but I’m gonna sit with it and trust that each other has a vision.”

Chowenhill, who is trained as a composer in the classical tradition, is responsible for most of the jaw-dropping guitar theatrics on the record, influenced by shredders like Alexi Laiho and Eddie Van Halen alongside Hungarian composer György Ligeti—in particular Ligeti’s “String Quartet No. 2.” “There’s no guitars, but you can transpose those things to guitar,” he explains, naming the composition’s chromatic motion and left-hand techniques as things he considered while composing leads. His tremolo picking, in particular, is astonishing. That comes from worship of heroes like Van Halen, but also mandolin players like David Grisman and Chris Thile.

“We’re in this weird era right now where it’s actually more rare to not be hearing musical sound than it is to be hearing it.”—Dan Meyer

While Meyer drew Zen Buddhism concepts into the record on songs he composed, Levinson took inspiration from literature produced during and after the AIDS epidemic in the U.S., especially David Wojnarowicz’s Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration, a collection of essays reflecting on the crisis. Poet Ted Berrigan’s classic The Sonnets was also in view. They spurred Levinson’s lyricism toward “looking at suffering and spirituality in a quotidian sense”—an interesting exercise on a record of volatile music.

Leah B. Levinson’s Gear

Basses

Ibanez SR505E 5-string

Ernie Ball Music Man Sabre

Amps

Ampeg SVT-4 Pro head

Peavey 2x15 cab

Effects

Ibanez Pentatone Gate

One Control Mosquito Blender

One Control Black Loop with BJF Buffer

MXR M306 Poly Blue Octave

Electro-Harmonix Green Russian Big Muff

Catalinbread Carbide

Electro-Harmonix Canyon

Old Blood Noise Endeavors Haunt

Darkglass Microtubes B7K V2

Strings & Picks

Ernie Ball Regular Slinky Bass 5 strings

Dunlop Tortex Flow 1.5 mm picks

Dan Meyer’s Gear

Guitars

Custom Jazzmaster copy

Amps

Peavey 6505+ (studio)

Fender Blues Junior (studio)

Orange Pedal Baby 100 (live)

Randall Diavolo 4x12 cab

Effects

Line 6 Helix LT

Strings & Picks

Ernie Ball Skinny Top Heavy Bottom strings

Dunlop Max-Grip Jazz III picks

Richard Chowenhill’s Gear

Guitars

EVH Wolfgang HT

Amps

Peavey 6505+ (studio)

Fender Blues Junior (studio)

Orange Pedal Baby 100 (live)

Randall Diavolo 4x12 cab

Effects

Morley Steve Vai Mini Bad Horsie

Line 6 HX Stomp

JHS Muffuletta

Strings & Picks

Ernie Ball Regular Slinky strings

Dunlop Primetone Triangle Grip 1.4 mm picks

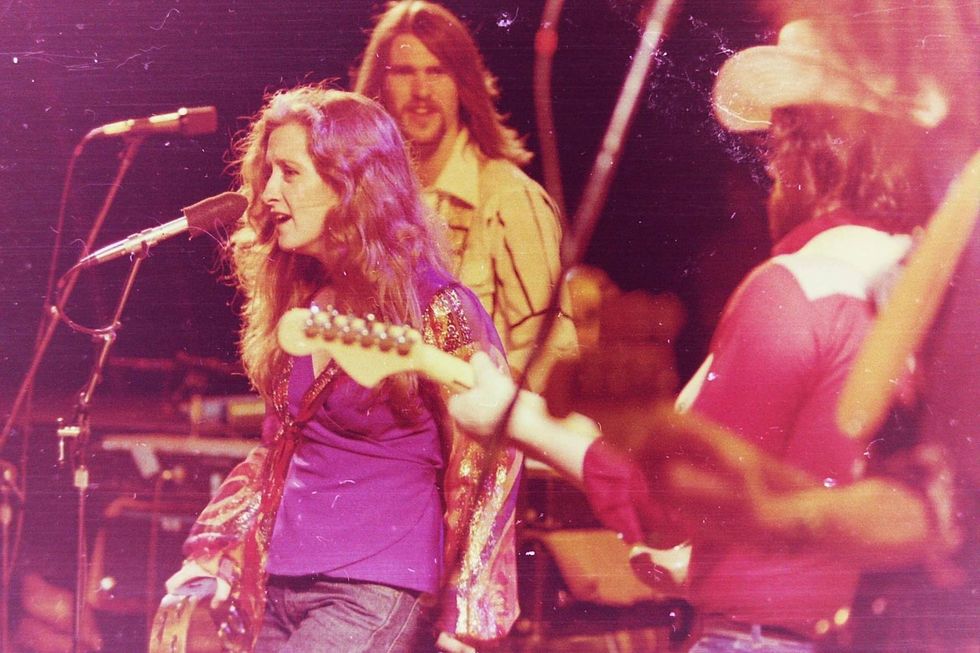

Agriculture blast through a live set at the Roxy in Los Angeles.

Bardic Roots

“I think when you’re working in extreme music, so much of the impulse is, ‘I have to talk about something extreme and I have to be dramatic, I’m gonna be screaming these words, they need to be about intense and immediate suffering and violent images,’” says Levinson. “The problem that I was trying to solve with my songwriting on this record was, ‘How do I write about things as they occur in my life and in my world without overly dramatizing them or without making them too much of a spectacle? Not presenting spectacles of suffering, but just how things exist in the everyday.”

“We pose this record as a rejection of ‘the vibe,’ but on the other side of that, it’s an invitation. It’s an invitation to listen, to just sit and be with us for a while.”—Richard Chowenhill

The ordinary, unremarkable facets of life, more than anything, are at the heart of Agriculture’s approach to making music—especially when it comes to the consumption of art. “We’re in this weird era right now where it’s actually more rare to not be hearing musical sound than it is to be hearing it, right?” says Dan Meyer. “We hear it everywhere, at every restaurant, in the grocery store, in the car. I think Spotify is bad. I think that flattening music into something that people just think of as sonic perfume is negative for music as a practice, both artistically and spiritually, and for us as listeners.”

“When we were writing these songs,” continues Levinson, “it’s not like we were thinking, ‘We’re gonna make some anti-vibe music.’ I don’t think that would sustain the compositional practice. A lot of these songs were really written with a mind towards live performance. I think people are pretty engaged when they’re watching us and it’s sort of a what-are-they-gonna-do-next-type thing.” Levinson says Agriculture’s work isn’t exactly “body-moving music” in the way that more groove-oriented metal is. “That’s not the show we’re selling. It’s like, stand there and look at it and be confused for a bit, and be interested and be excited, and go through some emotional experience.”

Meyer parallels the experience with the way that kōans, the reflective prompts of Zen Buddhism, demand attention. “I think that’s kind of what we’re going for,” says Meyer. “It’s like we’re waving our hands a little bit, like, ‘pay attention.’”

Chowenhill’s classical bonafides certainly contribute to the cinematic scope of Agriculture’s music. It also lends the sort of compositional depth that rewards repeat listens. “We pose this record as a rejection of ‘the vibe,’ but on the other side of that, it’s an invitation,” he says. “It’s an invitation to listen, to just sit and be with us for a while, as long as you’re willing to be here.”

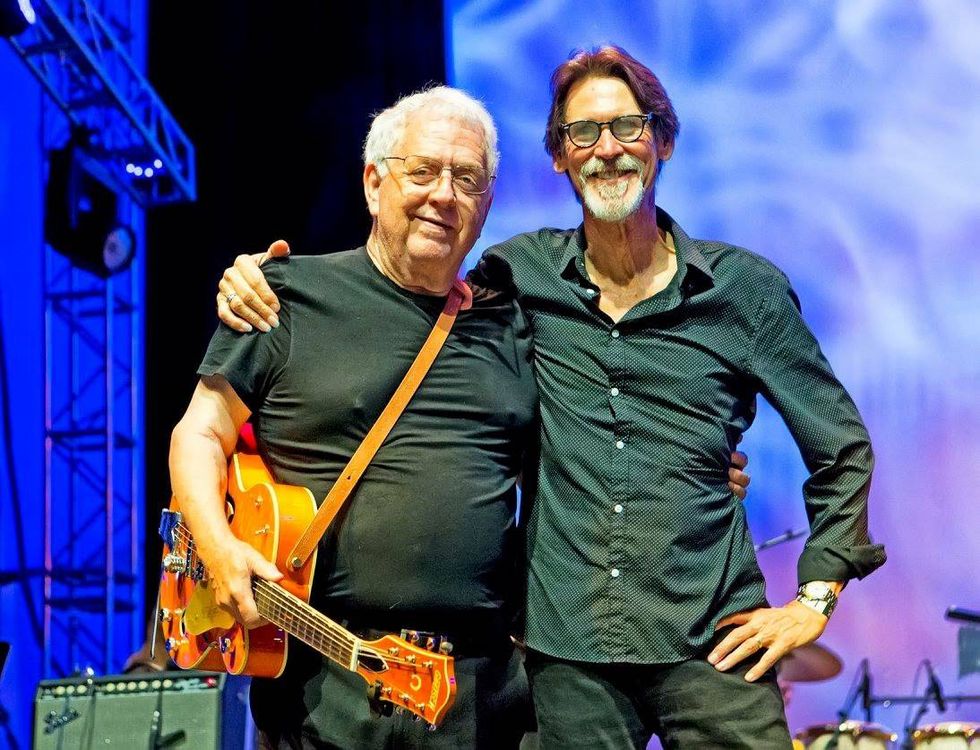

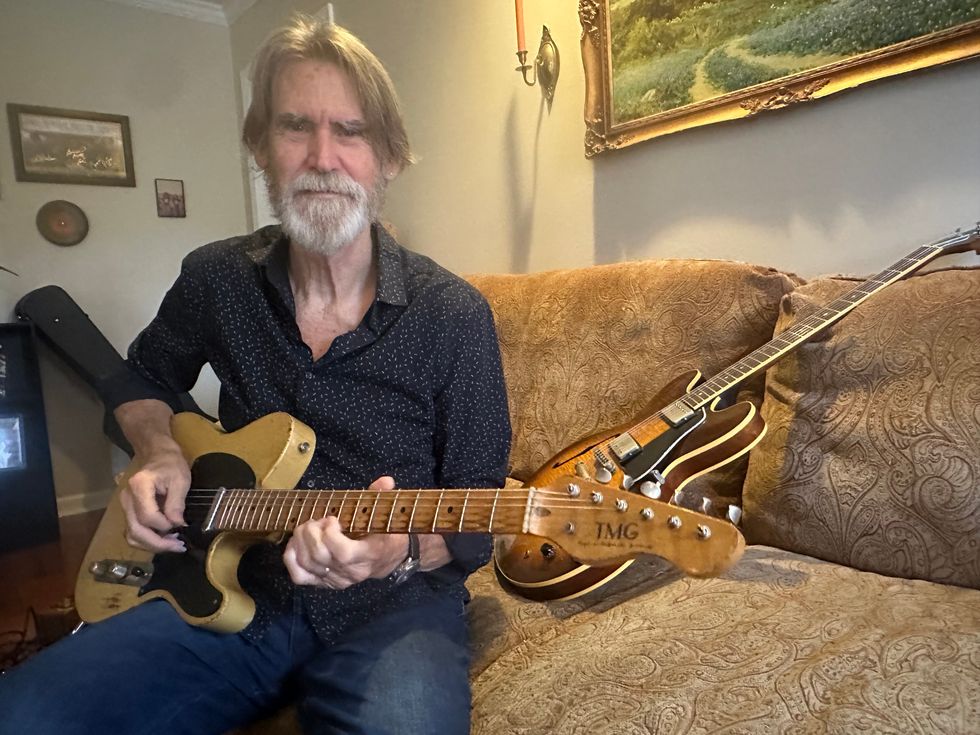

Will McFarlane keeps a Deluxe Memory Man in line with a Princeton—his rig for noodling on the couch at home.Ted Drozdowski

Will McFarlane keeps a Deluxe Memory Man in line with a Princeton—his rig for noodling on the couch at home.Ted Drozdowski