There’s a good reason why Tony Levin has played with many of the world’s most thrillingly creative musicians—a list that includes Peter Gabriel, Robert Fripp, Adrian Belew, Paul Simon, Bill Bruford, Manu Katché, David Torn, Tom Waits, Warren Zevon, Richard Thompson, Allan Holdsworth, David Bowie, Vinnie Colaiuta, Bryan Ferry, and more.

He’s one of them.

In the six decades since Levin graduated from the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York, and joined a freaky band led by members of the Mothers of Invention, he has brought his open-minded mastery of the bass and Chapman Stick to hundreds of sessions and thousands of performances, ranging from Simon’s “50 Ways to Leave Your Lover” to the magical ’80s incarnation of King Crimson. Even after all of that, the tall, shaven-headed, and prominently mustached Levin insists that “Everything about my playing is evolving. I’m much more a student than a teacher. Also, I’m very lucky to often play with great drummers and guitar players who, sometimes by their work ethic alone, but often by their musicality and talent, inspire me to try to deserve to be in a band with them.”

“The musical inspiration from really special players is what I’m here for, and King Crimson has been an unbelievable experience for me in that sense.”

The feeling is presumedly mutual, at least judging by the signposts along the path he’s taken since studying classical music and jazz. In the early ’70s, he played with Gary Burton and Herbie Mann, and became an in-demand pop and rock session player. (In 1971, he declined John McLaughlin’s invitation to join the Mahavishnu Orchestra, because he’d just taken the Burton gig.) In that decade, he contributed to such important albums as Lou Reed’s Berlin and Alice Cooper’s Welcome to My Nightmare, and cut tracks for Carly Simon, Don McLean, Phoebe Snow, Ringo Starr, Art Garfunkel, and Laura Nyro. He also began his long and still-ongoing association with Peter Gabriel, who’d left Genesis for a solo career and pressed Levin into service for his now-classic debut album.

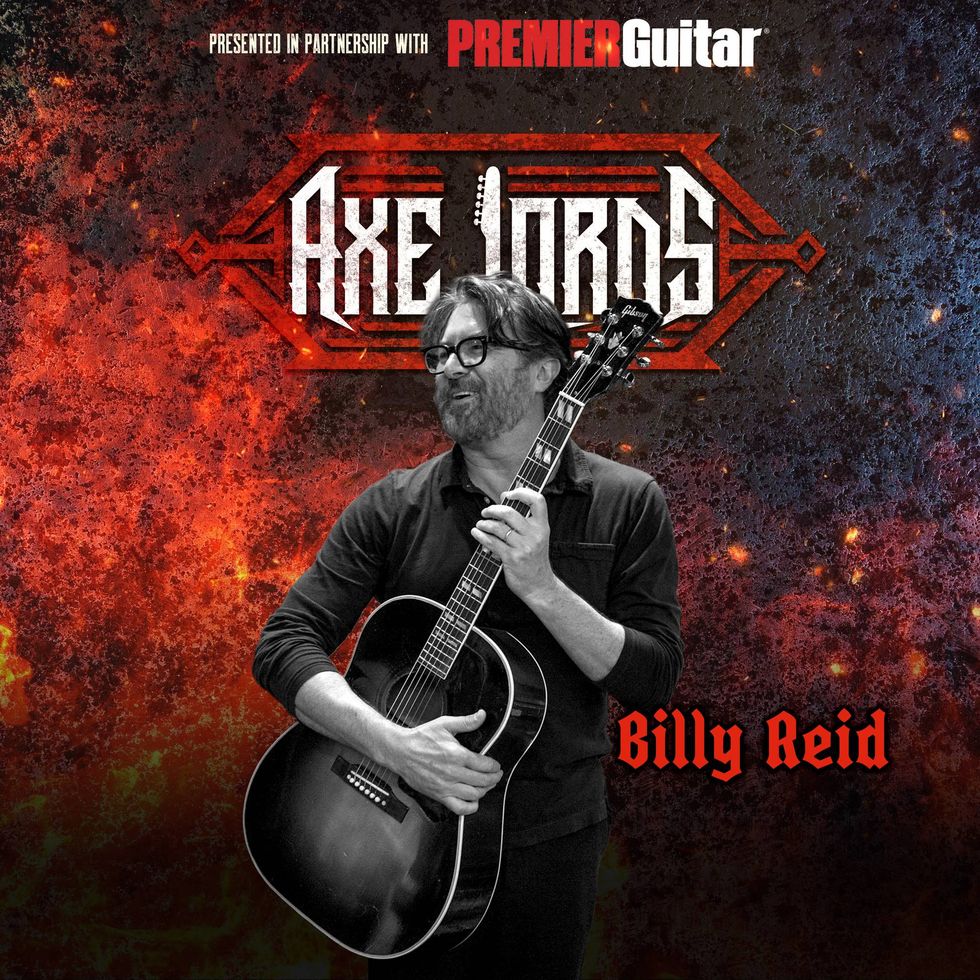

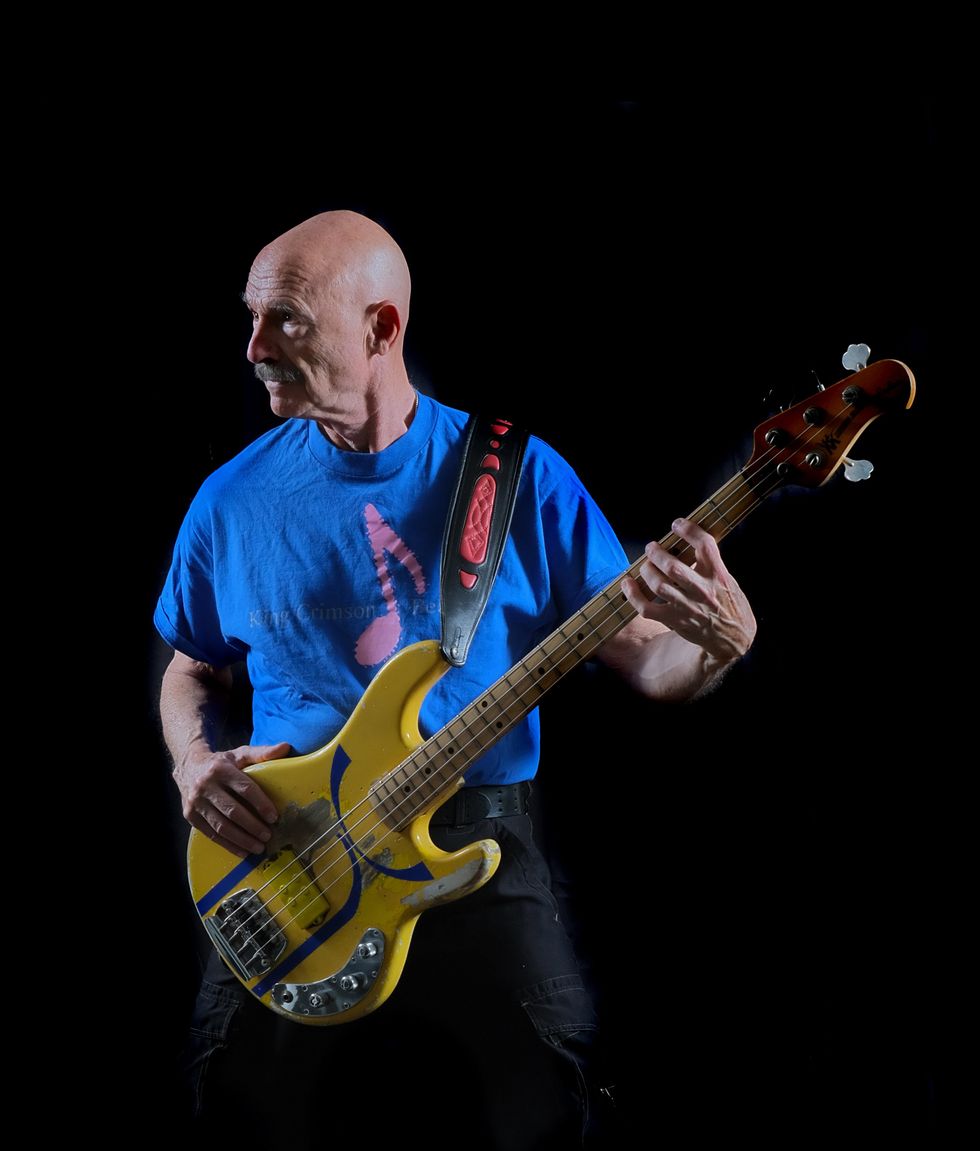

Say hello to Mr. Natural, Tony’s Ernie Ball Music Man StingRay with most of its finish sanded off, “the way we did with Fender basses in the ’50s and ’60s,” he says.

Photo by Tony Levin and Avraham Bank

Always searching for the ultimate bass sound, Levin was an early adopter of the Music Man StingRay in the mid ’70s, which increased his popularity with studio engineers, who were perpetually on the hunt for more and better lows in their tracks. His distinctive approach, derived from playing upright, also helped, with his authoritative fundamentals, slides and slurs, hammer-ons, and bends bringing character to the basslines he recorded.

Similarly, Levin acquired a Chapman Stick shortly after he learned of its existence, and that bass-guitar hybrid became an important part of his sound on King Crimson’s Discipline album, the 1981 declaration that Robert Fripp’s historic prog-rock project had returned to active duty. Many consider the Fripp-Levin-Bruford-Belew period, and in particular that album plus 1982’s Beat and ’84’s Three of a Perfect Pair, to be King Crimson’s zenith.

Levin’s days with Crimson, which, with a few breaks, extended to the group’s final tour in 2022, along with his tenure with Gabriel are enough to qualify him as prog- or art-rock’s reigning bassist. But there’s more evidence of his right to that crown found in albums by Anderson Bruford Wakeman Howe, Yes, the Crimson spin-off ProjeKct One, Liquid Tension Experiment, Steven Wilson, his band Stick Men with Crimson drummer Pat Mastelotto and touch-guitar player Markus Reuter, and his solo recordings.

On September 13, Levin will deliver a new solo album, the voraciously creative Bringing It Down to the Bass. Within, he shatters the genre-barrier, with elements of jazz, rock, blues, classical, and ambient music woven into its colorful fabric. There’s even a barbershop quartet arrangement, “Side B / Turn It Over,” with Levin—who is an exceptional harmony singer—vocalizing with himself. (For hardcore fans, it’s a reminder of his wonderful lead vocal turn on that first Gabriel album, the song “Excuse Me.”) The cast is, of course, stunning: guitar heroes Dominic Miller (from Sting’s band), Steve Hunter (who Levin has collaborated with since they played on Gabriel’s debut), Earl Slick, David Torn, and Fripp; drummers Katché, Jerry Marotta, Colaiuta, Mike Portnoy, Steve Gadd, and Mastelotto; Levin’s older brother Pete and the legendary Larry Fast on keys; and the violinist L. Shankar.

Bringing It Down to the Bass rocks, weirds, and entrances. The ambient piece “Floating in Dark Waters,” with Fripp and Marotta, is beautifully meditative, with Levin’s prayerful, semi-sweet-chocolate bass tones gently singing. “Bungie Bass,” with Torn, is a wild, expressionistic ride—full of playful cat-scratch and hide-and-seek melodies. And “Beyond the Bass Clef,” with Shankar’s sonorous lines in the lead, is a poetic journey through inner space.

“Just think about where Robert Fripp and Adrian Belew are sonically. When you hear them, you know who it is because of the way they sound.”

Something else that’s audible in Levin’s eighth solo album is his sense of joy. It’s long been ingrained in his musical character—audible in his tone and the way he reaches for high notes on bass, and in the melodies and rhythms he taps out on Chapman Stick, and in the driving, rock ’n’ roll pleasure of his album’s duet with Colaiuta, “Uncle Funkster.” It’s also in the bold horn arrangements on the title track, which sounds a bit like the theme for an imaginary ’60s TV detective series, and the glorious thunder of “Road Dogs.”

Joy will be in the house—onstage and in the seats—on the dates of the upcoming BEAT Tour, which ignites in mid September. It reunites Levin and Belew, playing that sacrosanct ’80s Crimson repertoire with new teammates Steve Vai and Tool drummer Danny Carey. It might not be the biggest tour of 2024, but it is one of the most anticipated, and it’s hard to imagine a better rock quartet.

Tony Levin's Bass Gear

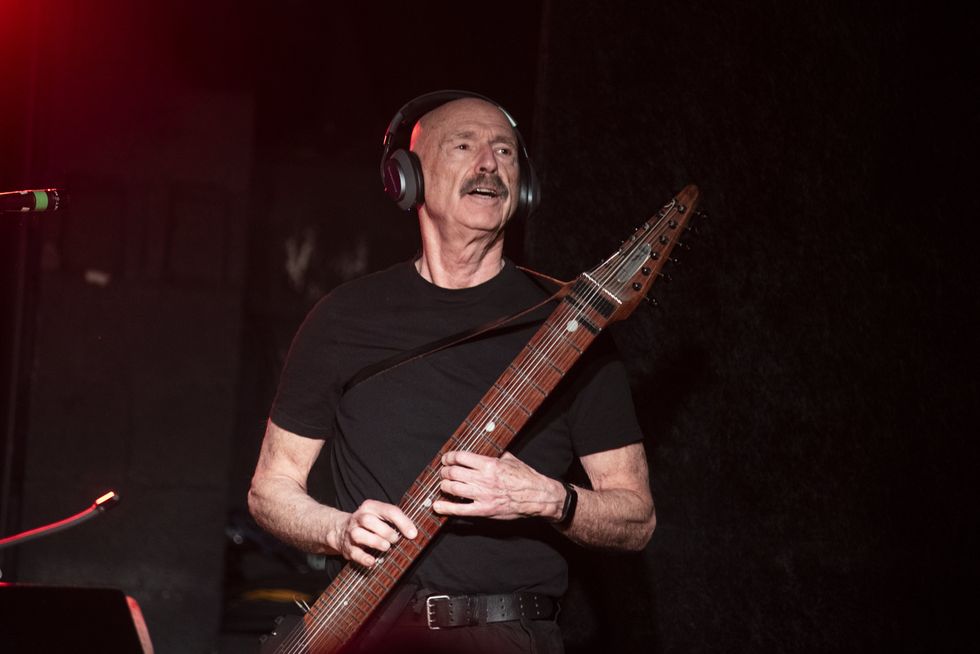

Tony Levin onstage with Stick Men—a band named for Tony’s use of the Chapman Stick, of which he was an early adopter, and Markus Reuter’s deployment of touch guitar.

Photo by Mike White

Basses

- Ernie Ball Music Man StingRays (4 and 5 string)

- Ernie Ball Music Man Sabre

- Ernie Ball Music Man StingRay Specials

- Ernie Ball Music Man DarkRay

- Chapman Stick (10- and 12-string instruments)

- NS Design NS Design EU Series Upright bass

Amps

- Ampeg SVT

- Ampeg SVT Plugins

- Various Ampeg combos and cabinets

- Kemper Profiler

Effects

Strings

- Ernie Ball Regular Slinky (.050–1.05)

Returning to the playful, ambitious, and elegant music on Discipline, Beat, and Three of a Perfect Pair is a challenge that Levin embraces. “It’s going to be really exciting and it can go in a whole lot of different ways,” he says, as we speak via Zoom from his home in upstate New York—his recording setup and a flotilla of basses behind him. “I’ve got a huge list of pieces that we had to choose among. Where Steve and Danny are going to take it, I don’t know. Me and Adrian started together playing this music in the ’80s, but I am more than willing to go in different directions. I can’t wait till we rehearse at the end of August.”

Meanwhile, here is our conversation, which ranges from tone to Levin’s choice of instruments to the BEAT Tour, and through the past, present, and future.

Tony, you have a highly personal vocabulary. How did you develop your tone?

I never gave it any thought. It’s only when I’m asked about my playing that I ask my brain, “What in the world is it that I do?” Of course, we all make decisions with every note we play. And the tiniest movement of one’s fingers on the strings up and down, or which part of the fleshy part of your finger you use if you don’t play with a pick, affects it. I haven’t done the analysis. I started on upright and I’m no different than anyone who started on upright. You fashion the sound with your fingers and get as good an instrument as you can.

When I first got an electric bass, it was a Fender Precision. I found it had less latitude for sound than upright. In my opinion, all electric basses have less latitude. They’re going to sound a little bit more like themselves no matter what you do. When I started on electric, I put a little extra effort into making more extreme changes with my fingers in relation to how close to the bridge or neck I played—to try to not make it sound like the upright, but to be able to get the amount of variation that I was used to wanting musically.

As a kid in Rochester, in classical music school, a jazz band came to town. The bass player, Andy Munson, was playing this thing called the Fender bass. I didn’t know what the heck it was. I went up to him and said, “Tell me about that bass you’re playing. It seems to be electric and it sounds pretty good.” He said, “Here’s what you need to do. Go to Dan Armstrong’s in the Village and buy a used one.” There was no such expression as a “vintage” one. He said, “A used one will be $180; a new one would be $220.” I’m talking about in the 1960s. So, I got a used, ’55 Precision, a wonderful instrument, not realizing how lucky I was and how precious that instrument was. Before that, I had played an Ampeg Baby Bass electric, through a flip-top Ampeg B-15 amp, but it didn’t fulfill much of anything for me except you could hear it.

“I have names for all my basses.”

When I was at the Eastman School in Rochester, New York, I auditioned my first year for the Rochester Philharmonic. And the conductor just kept asking me to play louder. I had a nice little Italian bass that sounded beautiful—let’s call it a chamber bass. I think it was three-quarter size. I didn’t get the job, and I got a very large bass that was very loud, but, frankly, sounded pretty good but not as mellow as my other bass. Then, I auditioned and got the job. I had such a large and loud upright, and boy that helped when I started playing jazz gigs.

I probably overcompensated when I switched to the Fender bass and tried to get as many sonic variations as I could get out of it. And without thinking about it, I guess I gravitated towards a lot of slides to try to negate the frets. That’s a good album title: “Negate the Frets.”

Today, I have a number of StingRays and I have a couple of Sabres, which are like the StingRay, but with two pickups. I happened to play the Sabre on Peter Gabriel’s “Sledgehammer,” so for all of his tours since—even though I could play it on a fretless StingRay—I’ve used the Sabre. By the way, I love what Peter does and his new music is extraordinary, but it’s still a hoot to play “Sledgehammer,” even after so many years in concerts.

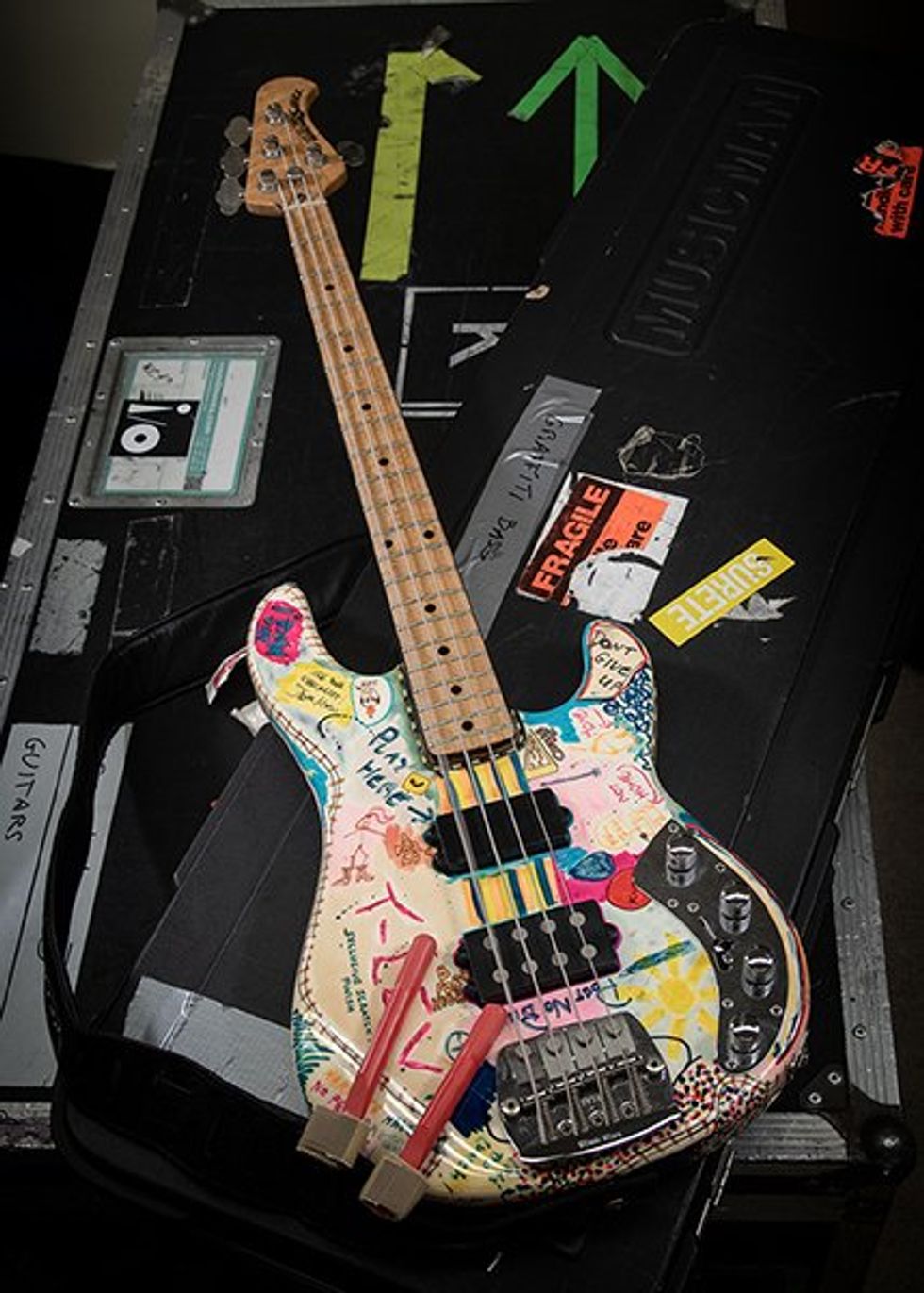

Another of Tony’s favorite instruments is his Graffiti Bass, shown here with its road case and a pair of his Funk Fingers—an invention suggested by Peter Gabriel that he brought to life with the help of tech Andy Moore.

Photo by Tony Levin and Avraham Bank

Who was in your ear when you were 10 and started playing bass?

My older brother, Pete, was and is my guide. He played classical before I played classical and he played jazz before I played jazz. Pete is a keyboard player now. When I grew up, he was a French horn player. Pete had landed on the wonderful records of Julius Watkins, the jazz French horn player. Julius Watkins played with the same rhythm section on a number of albums, including the bass player Oscar Pettiford. So, I grew up listening to Oscar Pettiford. His playing was fundamental and had just the right notes, and he was melodic when that was called for. In a way, I’m trying to do what I loved about Oscar Pettiford’s playing.

Do you feel like you’ve had any recent epiphanies or revelations?

This week [chuckles]? Seriously, though, there are some songs on my new album where I’m trying different things. For instance, hammer-ons, which is certainly the way I play on the Chapman Stick all the time.... I used the technique on a song called “Bringing It Down to the Bass.” Also, sometimes I play with fingernails and that’s a pretty distinctive sound, and I took one piece and kind of devoted it to a fingernail bass solo in the middle. That allows you to get various overtones from each note. There are also the Funk Fingers I developed years ago—a way of playing the bass with drumsticks attached to my fingers that, technically, can be a tad difficult and interesting. I have a long way to go to get better at that, even though I kind of invented it.

“An instrument that just gives you joy on the low notes is pretty special.”

What led you to the StingRay?

Very interesting story. Joel Di Bartolo and I were friends when I lived in Rochester, and he moved to L.A, and got the gig playing The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson. He befriended Leo Fender when Leo started Music Man, and Joel kept telling me, “You’ve got to try this bass. It’s got more low end. It’s got more of what you want.” And I was not being open-minded. But I was recording a lot in New York and engineers were always wanting more low end. When I finally started showing up with a bass that had it, the StingRay, the engineers were very happy.

The early ones Leo made had maybe too much high end, and would pick up a static electric noise. I had to keep the headphone wire very far away from the bass, or the bass would start picking up the click out of the headphone mix. But eventually those issues were worked out.

Tony Levin has long been a proponent of cutting edge instruments like those developed by Emmett Chapman and Ned Steinberger. Here, Levin plays his NS Design EU Series Upright bass.

Photo by Matt Condon

Let’s talk about Emmett Chapman and the Chapman Stick. How did that association begin?

I used to play the bass with a hammer-on technique on studio sessions—and maybe a little obnoxiously between takes. So, I was known by my studio pals for noodling and playing more than I should. And when Emmett announced that he had this new instrument designed for playing touch-style, simultaneously five or 10 guys that I worked with said, “Oh, you’ve got to check this out.” The next time I was in Los Angeles, I contacted Emmett about buying a Stick from him. I didn’t really want to try it. I said, “Let me buy it.”

The next time I was in L.A., we got together for a lesson, but also to just chat about the instrument and what it could do. And subsequently, Emmett saw me with Peter Gabriel and saw for the first time his instrument with a few thousand folks in the audience. And he was, as you can imagine, very pleased. So, we’re both friends and colleagues, and I think we’ve both learned from each other. I used it for the tour of Peter Gabriel’s first solo album, so that’s ’76.

I went to use it on that album’s sessions, which included Robert Fripp—a guitar player I did not know at the time. I pulled out the Stick to play it on one piece and the producer, Bob Ezrin, said, “Put that thing away. I don’t even want to see it.” So, I did not play the Stick on Peter’s first album. But when we played live, I began learning the Stick better by playing it on the simpler songs. It was a little hard to control at that time, to keep the open strings from ringing in a loud rock context. The instrument really had not been played in a rock context yet. And frankly, the pickups were so active that any amp would pick up footsteps on the stage. And there were plenty of footsteps on the stage with Peter Gabriel running around. So, I had to adjust it for that. And when I shared that information with Emmett, he quickly changed the pickups, and it became an ideal instrument for live shows.

“Imagine a band with Danny DeVito, among others, wearing only a diaper and body painted red, improvising dancing around the stage.”I got it to play as a bass, and what appealed to me was not just the technique that you play it with, but it has a different sound that I envisioned being useful for me in the progressive rock world, which I was becoming more and more involved with—especially with King Crimson. So, by ’81 when I was writing music with King Crimson, the Stick became probably 50 percent of the time the tool that I went to. The tuning in fifths [on the bass side] is very different, being strung backwards from a regular bass. All of that helped me break away from the usual habits I had as a bass player and helped me be a more progressive player, which is what I sensed I needed to be in that context.

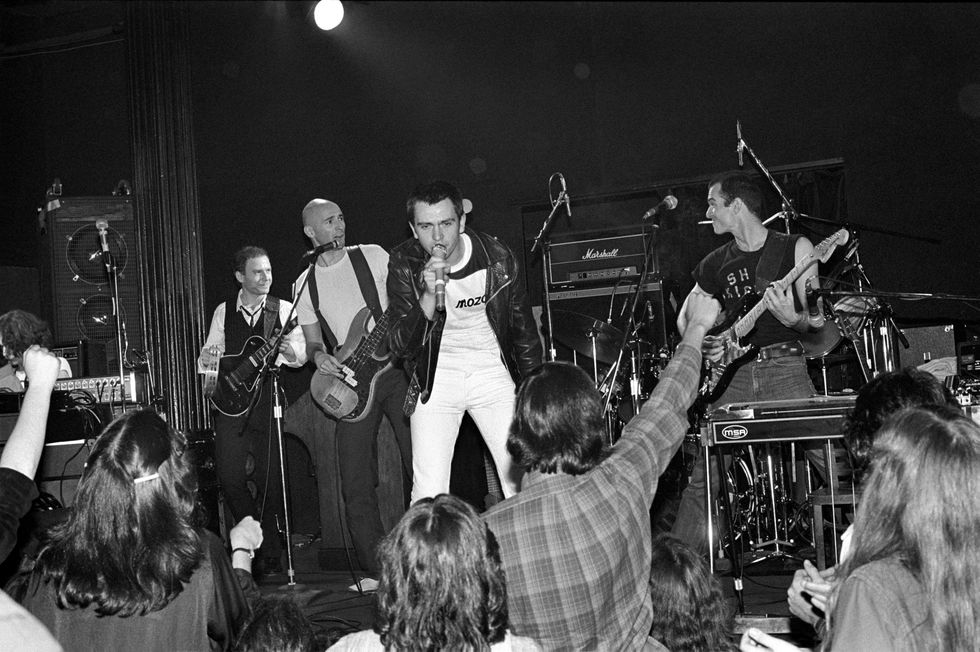

Peter Gabriel and his band live at the Bottom Line in New York City on October 4, 1978. At left: Robert Fripp and Tony Levin.

Photo by Ebet Roberts

Since we’re talking about playing percussively—and progressively—let’s talk about the invention of Funk Fingers. You first used those on a Peter Gabriel recording?

Yes and no. In ’85, we recorded Peter’s So album, and one of the pieces on that is called “Big Time.” And I asked, for no particular reason, while we were recording, the drummer, Jerry Marotta, to drum with his drumsticks on the strings of the bass while I fingered with my left hand. Just seemed like a good idea to attack the piece that way. And we had fun. It ended up only being used on the intro to the piece, which, frankly, disappointed me. But it was very cool and very effective.

Fast forward to the next year, when we were touring, and I am practicing in between pieces. I was trying to play with one drumstick in my right hand what Jerry had done with two drumsticks. Of course, I couldn’t do it, but I was trying my best. And Peter—I vividly remember the soundcheck I was practicing at—walked by me and looked at me and he said, “Why don’t you put two drumsticks on your fingers?” So, with that sentence, he invented the Funk Fingers. I turned to Andy Moore, my bass tech at the time. I said, “Andy, can we do that?” The two of us experimented with stretch Velcro and chopping down sticks. If the sticks were too heavy, they would break the string. If they were too light, they would just bounce off. If the Velcro was too tight, my fingers turned purple. If it was too loose, they would go flying into the audience, which happened a lot on that tour. Eventually, we got just the right formula. I then decided to make them myself to try to share them with other bass players to see where it could go. I got tired of making them pretty quickly, and somebody else got interested in making them, which is great. But for years now they haven’t been made, but I’ve had great fun through the years with the Funk Fingers, and I still use them. But how about Peter? Talk about thinking outside of the box. That’s just the perfect example of it. But he’s done that musically, his whole career.

Let’s talk about your new album, Bringing It Down to the Bass. What struck me immediately is how eclectic it is and how wonderful all the playing is. I also enjoyed that you worked in a little barbershop quartet—which made me reflect on how joyful your playing often sounds.

Well, I love hearing that. And I think the album encompasses a lot—some of it serious, but then some of it, especially the photos that go with it, whimsical and humorous. That’s just the way I am. And if it comes out in my music, that’s the way it should be, I think.

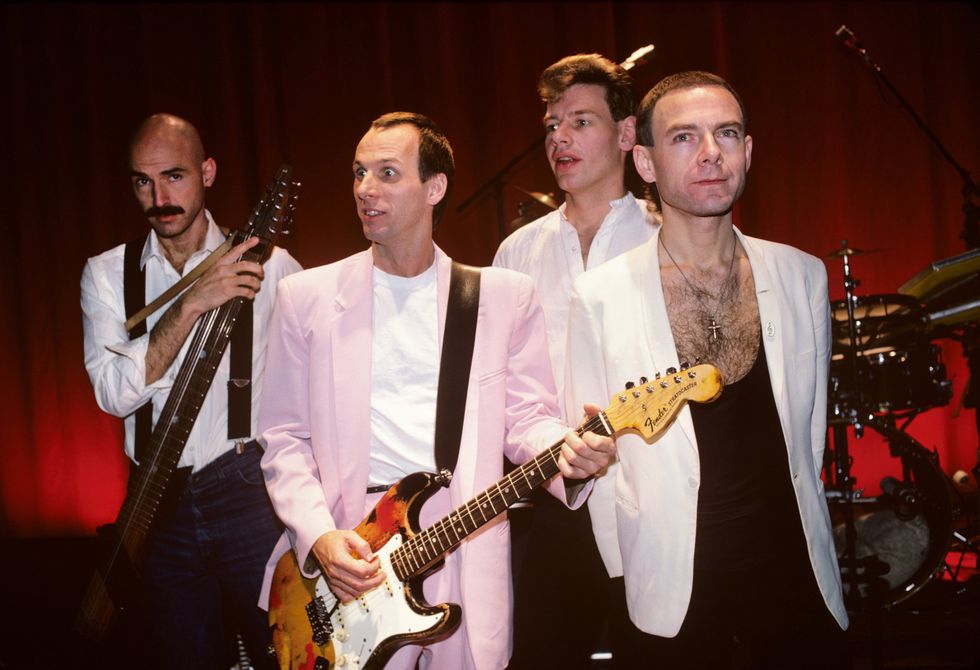

This photo was taken before the historic 1981 line-up of King Crimson went onstage at the Savoy in New York City on November 7 of that year. From left to right, that’s Tony Levin, Adrian Belew, Bill Bruford, and Robert Fripp.

Photo by Ebet Roberts

There is such a large cast that file-sharing had to be involved.

Yes, and it came together over a period of years, even though the last three months I’ve been intensely working on finishing it. I have this problem about making a solo album, and it’s a very good problem to have: I get called to tour a lot. I get the opportunity to play live, which is my very favorite thing. I haven’t done the math, but if I’m home two months in a year, then a few of those weeks I’m working on my solo stuff and on other people’s music.

An interesting thing about this album is how it displays your command of so many genres: blues, jazz, rock, prog, vocal quartet.... There’s also a world-class group of guitar players, including Robert Fripp, Earl Slick, David Torn, and Steve Hunter. You played with both Steve and Robert on Peter Gabriel’s debut solo album in 1977—a fruitful recording for you.

The word genre comes up a lot. The genre of this album is bass. It’s all about the bass because the bass player and the sense of bass is consistent. My overall rule for this album was, “Don’t be afraid. Break the rules.” I could give you a number of examples where I did that, and one of them is genre.

Steve and I trade files often, usually for his music, and I heard him right away as the guitar player I would most like to have on “Me and My Axe,” sharing lead with my fretless bass in a kind of duet. And I decided on that track to reunite the original Peter Gabriel band alumni, with Larry Fast on synth and Jerry Marotta on drums. So, to me, that has extra resonance. If you’re lucky and get to make a record the way you want to, there are a lot of distinct joys. As a bass player, the chance to groove with these extraordinary drummers alone is enough to celebrate and give me a whole year of pleasure. And then reassembling the alumni of Peter’s band from way back was another pleasure. [Marotta, Vinny Colaiuta, Mike Portnoy, Jeremy Stacey, Steve Gadd, and Pat Mastelotto all play on the album.]

I especially love what David Torn does on “Bungie Bass.” His playing is so spacious, and the way he uses harmonics and varied tones makes for a real sonic playground.

David Torn and I are sort of neighbors. He lived in Woodstock and I’m nearby, and I lived in Woodstock for a long time. We met when he asked Bill Bruford and I to play on his Cloud About Mercury [1986], when he had the idea of asking two rock guys to come into what would’ve been otherwise a jazz album to see what happens. We’ve done a lot. He was in our band Bruford Levin Upper Extremities. You never know what he’s going to do, but it’s going to be wild.

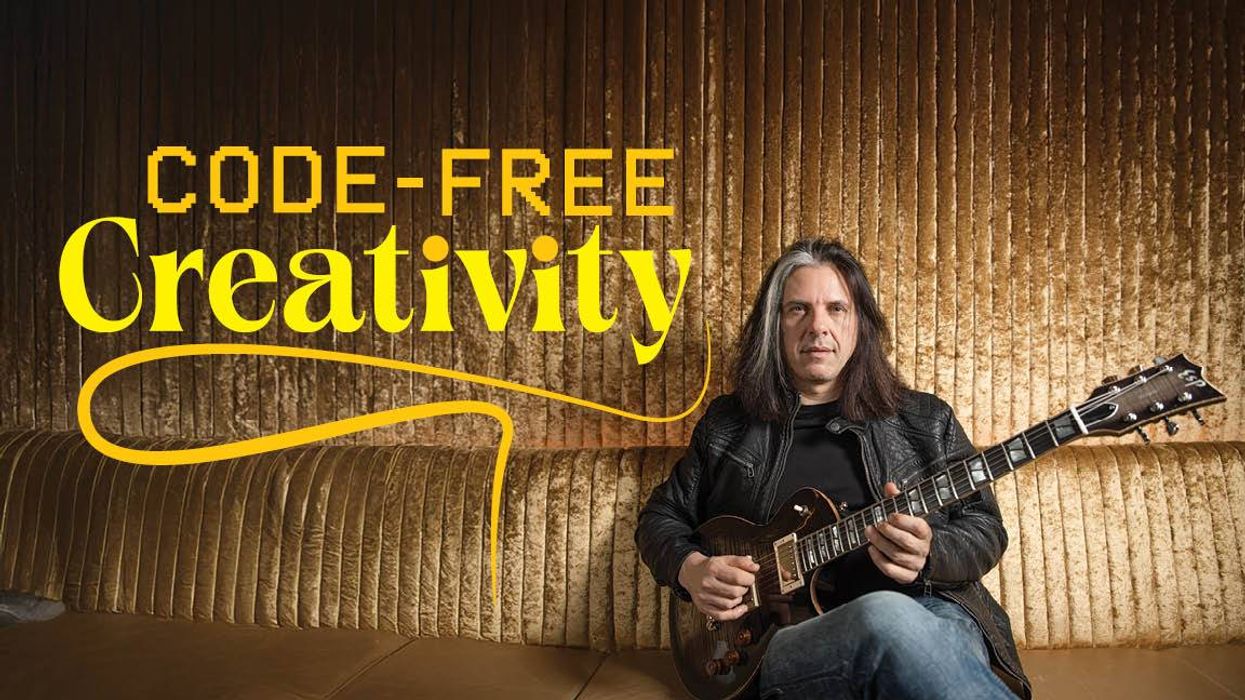

Men in black: This fall’s BEAT Tour players are, left to right, Tony Levin, Steve Vai, Adrian Belew, and Danny Carey, performing the music of King Crimson’s troika of classic ’80s albums.

“Bungie Bass” is also one of the songs on the album where you play cello. Did you study that instrument as well?

Not at all. I own a cello—that’s how I’ll put it. I have it tuned in 4ths, like a bass, and I just kind of make my hands small and pretend it’s a bass, and I’m very comfortable. Oscar Pettiford, the first bass player I really dug—he puts down the bass and he plays the cello for a solo on his records. Ron Carter is also a very good cellist.

Returning to great guitar players, you’re about to revisit your ’80s King Crimson catalog with two of them—Adrian Belew and Steve Vai—for the BEAT Tour, along with Tool drummer Danny Carey. Simply … wow.

So far, we got together to discuss things, and Adrian and Steve got together to discuss guitar. There is a lot of work to do, and Robert Fripp is not there, so Steve has to play what Robert did or change it to be himself. When I’m in a context with the really, really special players, it pushes me to up my game and to try not to settle back into what I played in the ’80s. Although, frankly, I’ve been listening and some of those Stick parts are damn hard. I’ll be a little challenged just to learn what in the world I was doing! But okay—the Stick part is hard, but then add a vocal in a whole different time signature. That’s really tricky.

I loved the music we created for Discipline. It’s been a great thing to be musically inspired by Adrian, Robert, and Bill, and they’ve all changed my playing to some extent. And Pat Mastelotto, who joined the band in ’96—I’ve probably played more shows with Pat than with anybody.

In a way, I’m trying to do what I loved about Oscar Pettiford’s playing.

The musical inspiration from really special players is what I’m here for, and King Crimson has been an unbelievable experience for me in that sense. I had a bittersweet last tour in Japan in 2021, knowing it was the end of that incarnation and maybe any incarnation of King Crimson. I was counting down the shows and knowing this was the end of the many times I’ve played these pieces and it just kind of hit me—I was feeling the spirits of all of the bass players who had been in that band through the years and had inspired me and given me the unusual challenge of playing a part that’s iconic and yet trying to make it my own. When we started doing the classic material, I didn’t want to change it, but I did need to. And that’s a different kind of challenge than just trying to make up your own really good parts to a piece.

"I have this problem about making a solo album, and it’s a very good problem to have: I get called to tour a lot,” Levin says.

Photo by Tony Levin & Avraham Bank

How did you join King Crimson’s Discipline band?

I had toured with Robert in Peter’s band, and then Robert asked me to play on his solo album, [1979’s] Exposure. Which was not a King Crimson album at all, but darn, it sounds like King Crimson to me. And then, I got the call from Robert—not to join King Crimson, but to meet him downtown in New York City and play some music with some other guys. I found, a decade later, that I was being auditioned and passed. So, we started playing and they pulled out “Red,” a piece that I didn’t know. Of course, they all knew it. Maybe Adrian didn’t know it too well, but they wanted to hear how I sounded on that. Fortunately, in those days when I was a lot younger, I could learn things very quickly. They were pleased with what I did and we formed a quartet called Discipline. That was the name of the band. And Adrian and I, the two Americans, were kind of scratching our heads saying, that’s not a great name for a band. Then Robert decided to change the name of the band to King Crimson. So, I joined King Crimson in a backwards way. I joined the band that then became King Crimson because as always, Robert’s sense of what music is or isn’t King Crimson is the sensibility that determines what is King Crimson.

Well, it was a wonderful band, and I feel privileged to have been able to have heard it live as often as I did.

Thank you. And, of course, I was privileged to be in it. In 2000, when King Crimson were about to tour, I was busy on tour and couldn’t do it. Robert said, “Well, we’ll tour without you, and you can consider yourself the fifth man in the group. ” I love his sense of humor. Now people get to see his sense of humor on YouTube and Facebook. But they used to think of him as serious, serious Robert. But we in the band knew that he has quite a sense of humor. So, for a few years, I was the fifth man in a four-man group.

Robert’s sense of what music is or isn’t King Crimson is the sensibility that determines what is King Crimson.

You also played with Allan Holdsworth in the improv band HoBoLeMa, with Terry Bozzio and Pat Mastelotto. Did that band record?

We recorded every night. We formed that band and it was glorious from the first note of the first show. He was such an awesome improviser, unlike anybody else. And we loved it all. But Allan didn’t. He was great about us and very respectful, but he didn’t like his playing on any of it. That’s the built-in thing that he arrived with. We did a few tours, and after almost every show, Terry very enthusiastically said, “We got it. We got it on tape. This is going to be fantastic. Can we please release it? This is an album.” And Alan would say something to the effect of, “Oh no. I hate what I played.” That’s why we never put out an album. It’s an honor to play with him. Very inspiring.

You’ve sort of become, to my thinking, the leading bassist in prog- or art-rock. Was that a conscious choice or circumstances?

I fell into an open doorway. I played with Peter Gabriel because the producer Bob Ezrin thought I played well with Alice Cooper and Lou Reed on his recordings with them, so thought I would be the appropriate kind of bass player for Peter’s new direction. So, I fell into that and met Robert. And then when I played on Robert’s Exposure, that might be the first time I really was fully reacting to that style of music. And then in King Crimson in ’81, I was exposed to three guys who think in different ways musically than most of the guys I had played with, who really don’t want to play anything like the way it’s been played. Just think about where Robert Fripp and Adrian Belew are sonically. When you hear them, you know who it is because of the way they sound. So, thrown in that musical situation, I was given that challenge and went in that direction. I fell through that doorway and very happily.

It’s a bird. It’s a plane. No! It’s one of Tony Levin’s Ned Steinberger-designed basses in flight! Levin and Steinberger have a decades-long association.

Photo by Tony Levin & Avraham Bank

I feel you’ve also brought a progressive sensibility to other styles of music as well, like Paul Simon’s, for example. I know when I hear you on Still Crazy After All These Years.

Very interesting process working with Paul, because the way he uses players to get the music that he knows will be right for him is very internal. He’d go up to us one at a time in the studio and play his song on guitar and sing. And with me, he would play it and kind of sing the bass part that he envisioned, which was usually very melodic. And we would quickly come up with a wonderful part that I would’ve never come up with on my own—that was more melodic than I usually played at that time. A good example is “50 Ways to Leave Your Lover.” I played, not all roots, but long, high stuff, and at least some of that is based on what Paul sang to me. But then when it goes into the B section, the chorus, that just Mr. Bass Player, down Low.

Well, let’s talk about your gear. Shall we start with strings and work from there?

Well, I am a bass player. I never change my strings [laughs]. I think when I go on tour and I have a tech, which is about one tour out of five, he changes the strengths. And I look at him and I say, “Did you change my strings?’ And he says, “What? I always change them! [laughs].” I use the green Ernie Ball sets.

My go-to bass is a relatively new StingRay Special. They’re made with every element of the StingRay, but lighter weight. For StingRays, they just tweak the output a little bit in the low end in a way that, oh, I care a lot about. And so that’s my go-to. It doesn’t mean that I don’t play the other basses.

I fell into an open doorway. I played with Peter Gabriel because the producer Bob Ezrin thought I played well with Alice Cooper and Lou Reed on his recordings with them, so thought I would be the appropriate kind of bass player for Peter’s new direction.You can see here in the studio, in the assortment I’ve got there next to the recording console, is the bass that I’m using today on a track. I call that bass Mr. Natural [a StingRay Special with most of its body finish removed]. I have names for all my basses. At first, I said, “I don’t care about the lighter weight.” But the first rehearsal I did with it was, like, six hours, and it was great. I didn’t realize how sore my back got. Not from playing a two-hour show, but from a six-hour rehearsal. And I love rehearsing so that’s why I use it. I ordered the bass in yellow to match my Three of Perfect Pair bass. And on tour, it just hit me to sand the paint off the way we did with Fender basses in the ’50s and ’60s. Ultimately, though, I play it because it sounds fantastic.

Eat your heart out Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Here’s Levin and Bank’s take on the famed impressionist’s painting, Reclining Nude on a Couch.

Photo by Tony Levin & Avraham Bank

I play the NS upright electric, by Ned Steinberger, on a lot of records. Bass players will totally relate to this. You just play a low E on it, and everybody lights up. Everybody says, “that’s what I wanted on this piece.” They haven’t heard a part yet. I’ve just played a note. I don’t know what the science is, but it gives you what you want from the low notes on an electric upright bass. And an instrument that just gives you joy on the low notes is pretty special.

The Chapman Stick I have has 12 strings. I’m stuck with the 12-string only because some of the pieces I wrote for Stick Men involve the 12-string. So, I can’t go back to the 10 string, even though I’d kind of like that.

I usually don’t need many pedals for bass, but with the high-end of the Stick, I need a lot. Gradually I’ve gone to the Quad Cortex as my go-to effects pedal. I was using two Kempers and loving them, and I still love their sound and record with them, but the Quad Cortex has a wonderful thing for my playing the Stick—two inputs and two completely separate outputs. This wouldn’t matter to most bass players and guitar players, but the Stick is essentially two instruments in one. You’ve got to either have two completely different chains or one of these multi-units. And this one gives you two completely separate outputs. When I hit one button, suddenly I have different sounds on both the top and the bass end of the Stick.

You just play a low E on it, and everybody lights up. Everybody says, 'that’s what I wanted on this piece.' They haven’t heard a part yet.

I do use other pedals—especially in recording. On tour, it depends on what kind of tour. If it’s the BEAT Tour, I can take a trunk of pedals if I want. But if it’s a Stick Men tour, where I have a maximum weight when we fly or the whole budget of the tour gets affected, you just can’t take much. So multi-effects units are perfect. Same with Levin Brothers—the jazz band where I go easy on the pedals. Darkglass makes two bass preamp pedals that I really love that I rely on for distortion. I have a Music Man bass—the DarkRay—that has one installed in it, that I use with Peter Gabriel.

Live, when I use an amp it’s an Ampeg. I’ve still got my SVT for recording, although now I have SVT plugins, which I love. And when I tour with my jazz band, I take an extraordinarily lightweight 12-inch combo. More and more, it’s about what’s in your monitors and it doesn’t matter what you have onstage. And sometimes you have it miked—maybe for the drummer who wants to feel the low end. When I toured with Seal, that’s the last time I toured with an 8x10, because he wanted to feel the bass.

I‘m a classic science fiction buff, and there’s a great B-movie called The Green Slime, so I need to ask: Where did the name of the first band you joined after music school, Aha, the Attack of the Green Slime Beast, come from?

It was the name of the first band I was in when I moved to New York City, with members or former members of the Mothers of Invention, led by [keyboardist] Don Preston. Billy Mundi was the drummer and Ray Collins the singer. We had an extraordinarily unsuccessful career: one gig. But a lot of rehearsing and offers of record deals, which we turned down. I don’t remember why. I was the new guy in town, so I was going by whatever they said to do. We did one very interesting gig in Philadelphia, and then we went our various musical ways.

Don would have been very aware of that movie. If we weren’t enough weirdness for one gig, Don’s friend, Meredith Monk, and her dance troupe improvised to the whole show on stage with us. And one member of her troupe was a young and out-of-work actor named Danny DeVito. So, imagine a band with Danny DeVito, among others, wearing only a diaper and body painted red, improvising dancing around the stage while Don Preston plays this thing called a synthesizer that nobody had seen, with a Van de Graaff generator on top and a big green translucent dildo. When he pushed a red button, a flashing light would go up through the dildo. There were two people in the audience, because it wasn’t well promoted, to put it mildly, and one of them got intimidated and left. So, somewhere there is the one person who made it through that show. Kidding myself, I like to think it was the right band at the wrong time [laughs].

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)