David Torn is always in motion. If he’s not doing session work for artists as diverse as David Bowie, k.d. lang, Madonna, or film composer Howard Shore (of Lord of the Rings fame), he’s producing sessions for someone like saxophonist Tim Berne or Kaki King, mixing a big-band album, recording video-game tracks, writing large-form orchestral pieces, or composing his own film scores. Somewhere in there, he also finds time to offer feedback to his favorite amp and pedal makers. “I also have a duet project in the works, but I can’t talk about it yet,” he laughs, “mostly because the other person doesn’t know about it.”

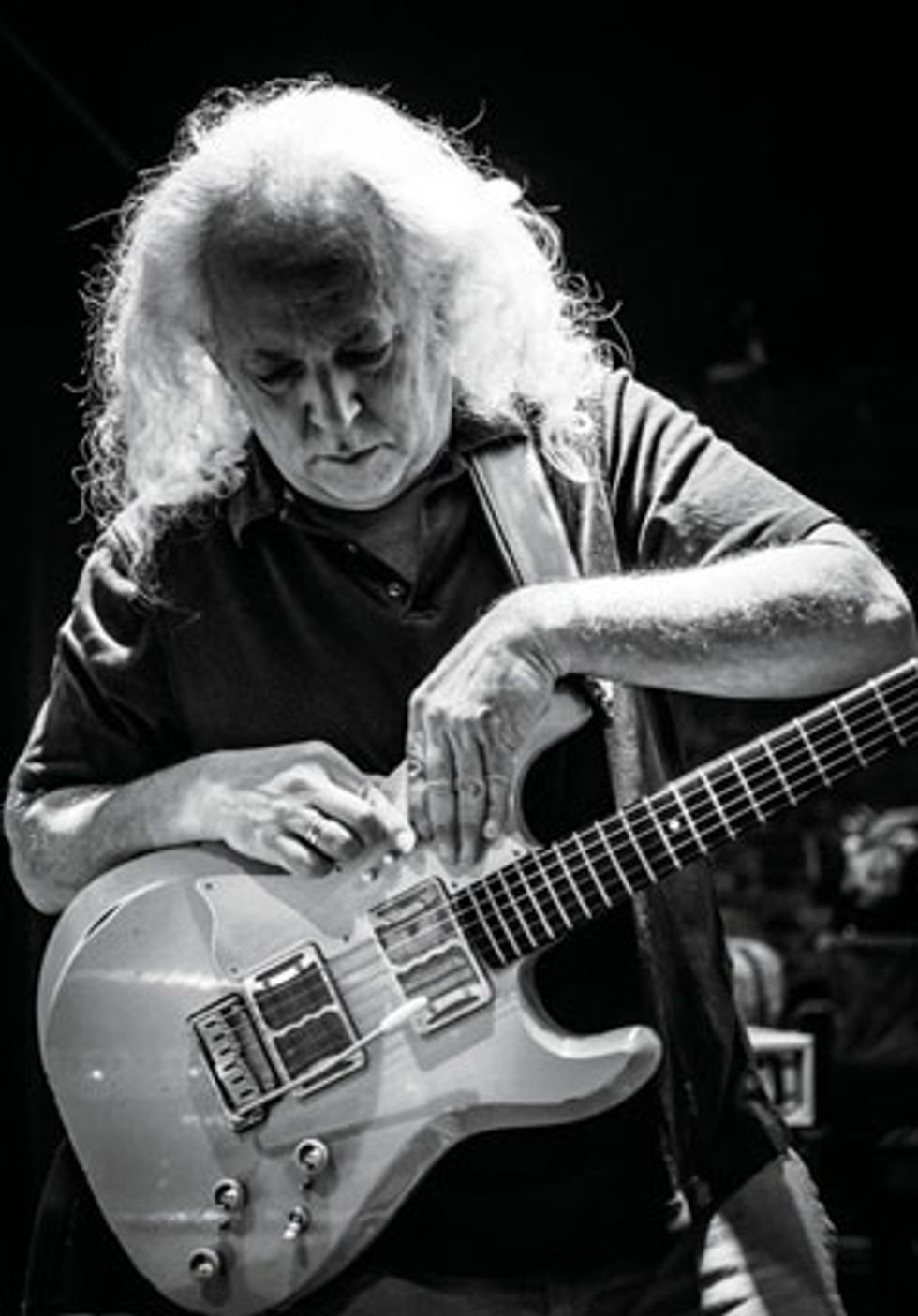

Fortunately for fans of adventurous, genre-defying guitar music, Torn also recently released Only Sky—his first ever solo-guitar album. But don’t think it’s some acoustic strum fest just because it’s nothing but guitar. Sure, the echo-laden electric tones of “Spoke with Folks” bask in simple structure and melody, but it wouldn’t be Torn without some stuttering weirdness thrown in here and there. In fact, more than anything, Sky is full of cinematically quirky soundscapes that longtime fans are bound to relish. “So Much What” is like a soundtrack to a troubling, surreal dream that ends with the reassuring dawn of a new day. Meanwhile, “Was a Cave, There…” finds Torn wielding his new gold-foil-equipped Ronin Mirari guitar like a glitchy, fuzzed-out theremin before descending into an atonal labyrinth of multitap-delay weirdness that would perfectly heighten tension in an opening scene from The Descent.

“Only Sky is easily the most personal album I’ve made,” says the Amityville, New York, native. “It’s real-time composition, but it’s about relaxing into it, enjoying the flow of sound, letting the music happen in its own time—and being open to the unexpected.” As Torn prepared for his first solo tour, Torn took time to discuss the musical meditations that fuel his creativity, balancing seemingly opposite musical careers, and his newfound love of fuzz pedals.

This is your first completely solo recording. What made you take the leap and commit to this approach?

I do these home recordings all the time and usually post them somewhere like the Gear Page or SoundCloud. The album grew out of the fact that a few people said I should do a solo album and let people hear what I’ve been doing in the background of other music for the last 35 or 40 years. When [ECM Records owner] Manfred Eicher first brought up the idea in 2005 or 2006 I was, like, “Yeah, I’ll do that but I’m going to do like three other records first.” I’m not the world’s fastest study when it comes to making records, so I only made the one record [2007’s Prezens]. This time around, I went “Ok. This is it. This is what I’m doing.”

Like the Koll Tornados Torn has used for years, the Ronin Mirari also features his “Tornipulator” circuit on the upper bout. The first button kills the guitar signal and activates a built-in Shaker mic (under Torn’s left hand) that takes in sound from the room and creates feedback. Button two introduces a ground lift and creates 60-cycle hum. Button three is a kill switch.

Photo by Peter Gannushkin.

Was the music entirely improvised or did you have some sketches that you took into the sessions?

Three or four pieces on the record—“Spoke with Folks,” “Reaching Barely, Sparely Fraught,” and “Only Sky,” and maybe “OK Shorty”—are improvised in very different ways than the rest of the record, and those were the ones that I did at home. The rest was much more free-form and exploratory. I recorded those at EMPAC [Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center] concert hall in Troy, New York.

How were those three or four pieces improvised differently?

I had this series going a couple of years ago, where I would get up and do this musical meditation. I just wanted to see how I felt in the morning. During the mornings when I would sit down for those solo pieces, I would talk to myself—like a crazy person. I’d say, “I want you to have an idea or a feeling and I want you to improvise as if it was a song. It doesn’t have to be a song or precisely in song format but it needs sections and themes and I want it to be improvised.” I would sit there quietly for two or three minutes and see what I felt. I didn’t want it to be like a mental exercise, so I would spend about half a minute touching the guitar and playing two or three chords, and then I would just play. I probably did about 40 days of that.

So they were kind of free-improv exercises?

“Free improvisation” has kind of developed this reputation as something that completely ignores the possibility of any kind of normalcy, any song form, any pentatonics, any major scales, any normal chords, anything that isn’t noise. If you ask a guitar player about free improve, they think of a bunch of saxophone players going wahhh, and to them it doesn’t make any sense at all. But if you’re playing with people who are similar to you and love all kinds of music, the improvisation is very likely not going to end up being like that—it’s not going to end up as one ostinato bass riff for 25 minutes. If you take into account a lot of different kinds of music and you’ve educated yourself to absorb those kinds of music, then you’re going to end up with something that is neither one of those two extremes.

What elements of those “meditation” songs would you say are different from the rest of the album?

In those pieces I am barely looping. There are just a few small loops, and there’s hardly any gear involved at all—just me, a Kemper Profiler, and occasionally a Hexe reVOLVER [glitch/stutter pedal]. I wanted to keep things super simple, but later I decided that it really wasn’t enough. When I decided that I needed to record in a big hall, I thought I should just bring most of my live rig. Once I got in there I thought, “Forget about the song form. Just do what you do. Be free. Make noise. Explore the rhythm. Do what you feel like.” I spent two or three days recording, and that’s the bulk of the record.

“I hate humbuckers, but I love these pickups,” David Torn says of the Foilbuckers in his Ronin Mirari. “I’ve been swapping pickups my whole life, but with these it’s been three years of ‘Wow, I love these!’” Photo by Peter Gannushkin.

Was everything recorded in one take, or did you go back afterward to overdub or tweak anything?

Everything was recorded in one take. There are a couple of little bits that were edited, but they are very small. In most cases, I would say that everything is a single take of something. There are two endings where I couldn’t stop myself from overdubbing something while I was mixing. I just thought, “This needs something else.” There are two endings that have acoustic guitar—one of them is with an EBow.

In a way, it must have brought you back to when you were a kid sitting in your room trying to figure out what to do with the guitar.

Yes, I still do that even when I’m actually working or writing. It’s the same thing for me. I am sitting there concentrating. I just set up and fiddle around with ideas and practice.

What types of things do you practice?

I practice tone production every day of my life. About eight years ago I started to make sure I play every day. I just got to this place where I had to continually fine-tune the way I interact with the electric instrument with just an amplifier. So I split my practice time to “with stuff” and “without stuff.” Today, I am actually going to practice with the Hexe reVOLVER because I got a new one that is quite different. I want to take it on the road because it does things that the other ones don’t do. I need to kind of learn it.

You do quite a bit of film scoring and studio work. How do you balance that with your solo albums?

Guys used to say you can’t be committed to more than one thing, and I’ve kind of struggled with that—because I want to make records. I want to make music that I want to make. In that world, I am definitely a slave to whatever the muse is, but the word “experimental” almost feels a little derogatory. I do follow the muse, but the muse doesn’t always take me to that place. While everything might be an experiment, I am not a lab coat guy. I see my own music in a hundred different ways.

David Torn's Gear

Guitars

Ronin Mirari with Foilbuckers

Koll Tornado

Teuffel Niwa

D’Pergo Aged Vintage Classic

Godin MultiOud

Amps

Fryette Aether

Fryette Sig:X

Fryette Two/Fifty/Two

Kemper Profiler

Bob Burt custom 2x12 with Celestion Blue speakers

Fryette Deliverance 2x12 with Fryette P50E speakers

Effects

Paul Trombetta Designs Tornita

Paul Trombetta Designs Mini-Bone

Fryette Valvulator I

Catalinbread Antichthon

Hexe reVOLVER I

Hexe reVOLVER DT

Two Lexicon PCM 42s (one modified by Gary Hall)

Neunaber Stereo Wet Reverb

DigiTech Whammy DT

Empress Compressor

TC Electronic Classic TC XII Phaser

Goodrich LDR-2 volume pedal

Caroline Guitar Company Kilobyte

Oberheim Echoplex Digital Pro w/ Aurisis Loop IV upgrade

Roland EV-5 expression pedals

Lexicon PCM80

Strings and Picks

Snake Oil Vintage Formula strings (.011–.048)

Agate pick (used occasionally since 1979, but mostly “just my little fat fingers”)

Rane SM82S Stereo Line Mixer (modified)

Mogami cables

But I also really enjoy working with pop people. When you have the opportunity to work with people like David Bowie, Tori Amos, k.d. lang, John Legend, or Meshell Ndegeocello and bring something to the table that is a little bit different, it’s awesome. I love it. On the other hand, I love improvisation. It has been a part of my life since I was a kid, in a real way, before any other music was. Then there is a side of me that used to be a songwriter. So I feel like I have to do that, and that is where my great love of stories kicked in. I have film scores that are very far from avant-garde. If you put Only Sky up against the score to Lars and the Real Girl you might think two different people wrote those. How many people do you know who have played with [trumpeter] Don Cherry and co-wrote a Madonna hit single?

Even before you started scoring films your music was often described as “cinematic” or “orchestral.” How did you get into film work, and what inspired you to write for large-scale projects?

From my perspective it was an accident. In the late ’80s I had started Cloud About Mercury and invited Mark Isham to be in my band because he was the only trumpet player that I knew who understood the concept of how loops might be used in a musical context that wasn’t just like playing over the loop. It was involved. It was contextualized. Little did I know, he was just getting his sea legs as a film composer. He said to me, “Dude, honestly, you belong in Hollywood. I want you to come to Hollywood with me and work on a few films. Let’s see how this goes.” We sort of became really close to being partners for a couple of years, and then that broke up and I came back to New York and that stuff didn’t really go away. Eventually, people like Howard Shore and Carter Burwell [The Big Lebowski] were calling me. Then [Steven] Soderbergh’s Traffic came up. I didn’t realize how big my role was going to be in it, because I was in New York and the score was being recorded in Los Angeles. At the time, I thought I was just part of the session and that there was going to be an orchestra. I didn’t realize until I actually saw the film that I was the score.

How has guitar technology inspired you recently?

I pay attention a little bit to what other people are doing, but not that much anymore. I do like to speak with amplifier designers and a lot of pedal builders, but more and more I’m back to talking about looping devices—because that is a huge part of what you hear on Only Sky. I’m just creating these loops and manipulating them in real time—sometimes without hearing them first.

What’s your favorite looper?

My regular looping rig is a modified Lexicon PCM 42—the first one made of its kind. [Lexicon designer] Gary Hall modified it around 1981 to have approximately 20 seconds of sampling/delay time. The originals only had five seconds. I have another PCM 42 that was modded to feature a reverse-play switch. I also have an Oberheim Echoplex Digital Pro, which doesn’t get as much use as it used to, and for a while now there’s been a single Hexe reVOLVER going into my regular pedalboard, not my wet rig. Now, I have two Hexe reVOLVERs and they do very different things. One is an original revolver, and the other is called the reVOLVER DT, which was fed by my ideas. I don’t think the DT will ever be a product, though—I think Piotr [Zapart, of Hexe Guitar Electronics] feels it’s just too difficult to do. [Laughs.]There’s always one extra looping device that I never talk about because I only use it on studio sessions. Lately, I’ve only used it with David Bowie.

Torn swaps out fuzz pedals often enough that he doesn’t mount them to a board, but the heart of his live arsenal is his loop-creation rack. This iteration of the loop rig contains Lexicon PCM 80 and PCM 42 units, an Oberheim Echoplex Digital Pro, a modified Rane SM82S mixer, and voltage-control pedals for varying loop levels. Photo by Scott Friedlander.

What’s the studio-only looper?

The looper I never bring on the road—because it requires a keyboard to control it—is the Electrix Repeater. I didn’t use it on Only Sky because I knew I wouldn’t be using it on tour. Each loop can be composed of four separately addressable tracks. And the multi-track loop can change pitch, time, or both simultaneously, in real time. Also, there’s full-tilt loop storage and recall.

Except for the Hexe, all those loopers are quite old.

I’ve been on this rant for a year on why looping devices suck. Why are looping devices from 25 years ago way better than they are now? The modern ones are so technologically behind the beat, it’s unbelievable.

What are your main beefs with modern loopers?

I have well-known beefs not with modern loopers, but with the folks who design and bring them to market. The major manufacturers of looping devices have created some really great things, but have ignored most of the more musically creative possibilities—which were established 20 to 30 years ago! And those possibilities have not even remotely been exhausted. I could go on and on, but in a nutshell my beefs are that new loopers are glorified, ridiculously un-ergonomic playback devices with little or no ability to alter feedback, oscillation, pitch, or time—and there’s no sequencing or randomization, either. And even the best new loopers have very limited undo, real-time editing, storage, recall, and mixing capabilities. While I absolutely appreciate that these things are being made at all, most of the current hardware loopers are incapable of competing with older technologies with regard to musical potential—which is a damned shame! That said, there are definitely a few intriguing builders and designers now afoot with the promise of positive developments.

What’s so unusual about the reVOLVER DT?

It’s simply a rebuilt reVOLVER II with two little sidecar pedals that offer instant changes to each of the pedal’s eight modes, with controls over both range and rate of change. It also lets me change between modes with simple foot taps.

How do loopers affect your amplification needs?

I always play in a minimum of stereo. Most of the time I only use two amps. One is dry and the other has the big reverbs and most of the looping. I have been using Fryette amps since around 2004. I have a lot of them and I love them all. I’ve also got a mixer with pre-fader sends, which is critical. Everything on the effected track is capable of feeding everything else, and I can change sends and returns in real time. Everything—every loop, every reverb, every send, and every return—has to be manipulatable in real time with as small a footprint as possible. I end up with quite a few voltage-control pedals on the floor.

What non-looping pedals are you using?

The pedalboard is usually pretty simple [see gear sidebar for details] except for the fuzz boxes, which always change. One fuzz that’s a constant is the PTD Tornita, a feedback fuzz that Paul Trombetta made for me. My fuzz thing went crazy this year—I just went nuts. I decided I actually needed to learn about it, so I started figuring out why they are all so different. I’ve got an insane collection of fuzz boxes. For this upcoming tour, I think I’m taking the Tornita, a Catalinbread Antichthon, and at least one Basic Audio fuzz, probably the Fuzz Mutant.

What is it that makes the Tornita so indispensable?

It sounds and feels burry and amazing. When the feedback is tuned and engaged, its feedback loop is quite controllable, melodically speaking, via the big knob and the guitar’s volume control.

What are some of the craziest or rarest fuzzes in your collection?

Oh! There are a few prototype pedals made by Paul Trombetta. I have a very rare Black Daddy pedal made for me by Sean Michaels of Lovepedal. There’s a lightly modified Marquis Enso made by Tim Cooper of Faceless FX, and—somewhere—an 8-Ball pedal made by Matt Wells. Some older, rare Skreddy fuzzes are great. I have a custom FuzzTool from GuitarSystems, and two amazing pedals made by Animal Factory Amplification out of Mumbai, India.

YouTube It

Armed with a Ronin Mirari, a Godin MultiOud, and a bevy of sonic toys, David Torn improvises a gloriously expansive soundscape, then recounts the tale of his horrifying 1992 brain-tumor ordeal to a rapt TEDx crowd at the California Institute of Technology.

Let’s talk guitars. Lately you’ve been playing a Ronin Mirari.

I’ve had a fantastic time ever since I got that guitar, and it’s partially responsible for my interest in fuzz because the pickups are just so great. It’s hard to imagine that you can be as old as I am and finally go, “Oh my god, I fucking love these pickups!” It was the first time in my life I could actually look at a pair of pickups, play them, and not focus on some weird tweaky thing that’s wrong. There are parts of this guitar that I don’t even like, but I can’t stop playing it because it sounds so good and feels great. The humbuckers are splittable, and the fundamental idea for the pickup came from the ’67 DeArmond “gold foils.” When I was working on David Bowie’s [2013] record, The Next Day, which was quite a few years ago—way earlier than you’d think [based on the release date]—I met the guys at Ronin. They were making these Hagstrom-type guitars out of old-growth redwood, and they had original gold foils in them. The DeArmond gold foils changed it all for me—especially when I played them in a guitar that was made well.

What’s so remarkable about the gold foils?

I’m in the studio more than on stage, and I have a lot of digital equipment. When I’m working on films, monitors surround me and the induction in the room is horrific. So Ronin came up with a design that essentially turns them into humbuckers. I hate humbuckers, but I love these pickups—I actually like them better as humbuckers than I do as single-coils. They are so woody and stringy, without being overtly bright. They have all kinds of grit when it comes to breaking up an amp. They do great with fuzz and amp distortion. Mine are completely unpotted and directly mounted into the body like the old gold foils were. I find it so odd: I’ve been swapping pickups my whole life, but with these it’s been three years of “Wow, I love these!” I don’t care about the squealing—I can deal with it.

It’s part of the charm.

It is part of the challenge anyway, right? It’s like feedback, except more horrible.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)