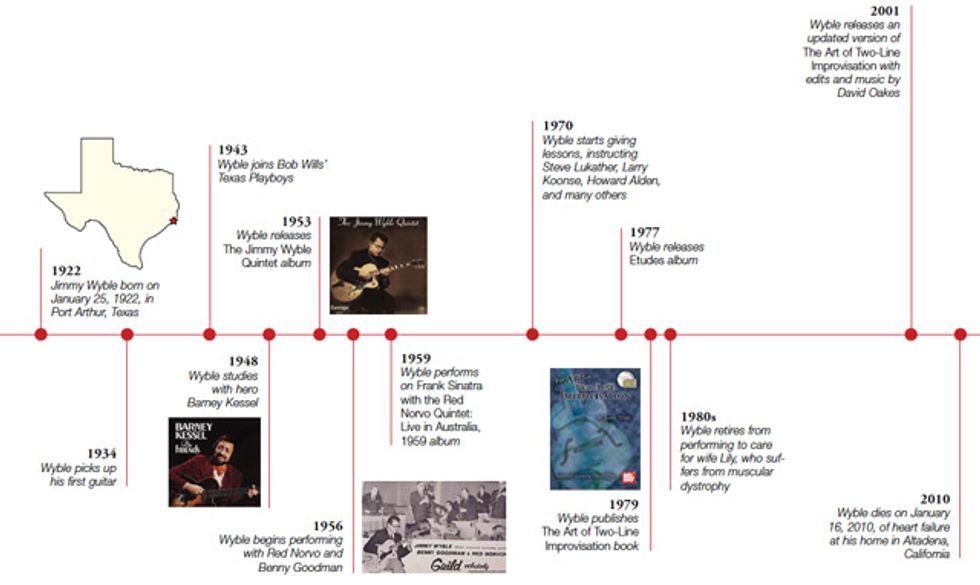

Born: January 25, 1922

Died: January 16, 2010

Best Known For: His contributions to Western swing and jazz, most notably his etudes and explorations of contrapuntal concepts and technique. Wyble was also highly regarded as an instructor.

When imagining a guitar genius, one might envision clichés of an eccentric artist, probably with unkempt hair, a tormented stare, and a whiff of madness. The genius leaves behind a list of broken relationships coldly sacrificed in obsessive pursuit of art. But sometimes that mold is broken. Sometimes the genius is surprisingly humble, generous, and caring. Sometimes a legacy is sustained not only by recordings and musical breakthroughs, but also by lives touched and changed. Such is the case with Jimmy Wyble, an incredibly talented guitar player and teacher who created a family tree of musicians built on sincerity and patience. He played country, Western swing, jazz, and classical music, yet it’s tough to find anyone who doesn’t mention Wyble’s personality first when discussing his proficiency on the guitar.

James Otis Wyble (January 25, 1922-– January 16, 2010) was born in Port Arthur, Texas, to Cajun parents who hailed from Port Barre, Louisiana. He began playing guitar at 12 and received lessons from a machinist at the oil refinery where his father worked. The teacher taught Wyble to read music, along with a few rudimentary chords. By his midteens, the young guitar player was performing with his teacher at parties and small dances. Wyble’s early influences included bands that passed through Port Arthur and Houston, along with the work of jazz guitarists Eddie Lang and Carl Kress, among others. The mixture of Texas country and Western music with Cajun influences provided the base, a sort of roux, if you will, to which later jazz inspirations would be added.

Student and close personal friend, Larry Koonse, has amassed an extensive discography and touring record, as well as being a faculty member at the California Institute of Arts since 1990. He says it’s possible within just a couple of notes to recognize Wyble’s work. It’s not so much the attack, the phrasing, or the tone that is easily identifiable. Instead, it’s the combination of geographical and genre influences.

“He had an identity and sound that was completely his own,” Koonse says. “It’s the mix of elements that exist in his playing due to where he grew up and the influences that surrounded him. He definitely has some of that New Orleans-style feel, even Cajun mixed with this Texas swing style that would be something you would identify with Spade Cooley or Bob Wills. Mixed with a New York jazz sensibility.”

Wyble moved to Houston after high school and played with a variety of bands, in addition to scoring a gig on KTRH radio station performing short snippets of tunes used in broadcasts. His teenage ability to read music was crucial in scoring this gig and was an indicator of his future proficiency with charts and sheet music.

By the early ’40s, his friends and bandmates were trading guitars for rifles and shipping out to World War II battlefields in Europe and Asia. Wyble, physically small to begin with, had poor eyesight that exempted him from the draft. However, he managed to enlist in the Army and was assigned to a marching band. Honorably discharged after a year, Wyble returned to Houston and began performing with a group of country music pals, including Cameron Hill.

In a 2007 interview with Jim Carlton published in Just Jazz Guitar magazine, Wyble describes Hill as a “guitar player who didn’t read a note but had a super ear. He could play several of Charlie Christian’s solos, like ‘Flying Home’ and ‘Soft Winds’ and we’d get together and make a two-guitar thing happen.”

Along with Hill, Wyble received a big career break when asked to join Bob Wills’ Texas Playboys in late 1943. The group toured extensively and ultimately went to CBS Studios in Hollywood to record versions of Wills’ staples “Ida Red,” “Take Me Back to Tulsa,” and “Roly Poly,” which stayed on the charts for a number of weeks in 1946.

Crossover Kid

Wyble returned to Texas and enrolled at

the Houston Conservatory of Music, but

only studied a short while before joining

Spade Cooley’s band. During his tenure

in Cooley’s outfit, Wyble was featured in

a 1950 Fender advertisement, decked out

in Western shirt and dark rimmed glasses,

holding a black Esquire model with a white

pickguard and his name emblazoned on the

lower side of the body. Other photos from

the era show him with a blonde Esquire.

Over the years, Wyble played a variety of guitars and chose whatever was best for the particular application, as opposed to sticking with a single trademark instrument. In addition to the Fenders, he also played Epiphones, Guilds, Gibsons, and Hofners, and later in life, instruments by Roger Borys, Paul McGill, and others.

Those later instruments are prime examples of Wyble’s generosity and thoughtfulness. Not only were they fine guitars that he used in his practice and performances, they were also gifts to the next generation.

“Jimmy’s plan was to have a few great guitar makers make a guitar for him, but he had them marked for his friends,” says Sid Jacobs, longtime friend and instructor at Musicians Institute. Wyble’s gifts were heartfelt gestures to the people he cared about and also intended to be working gear to benefit their careers. This person got the Borys, that person got the D’Angelico, and so forth. Larry Koonse received a Paul McGill, among other guitars.

“The McGill is a very fine instrument— a very pricey, handmade nylon-string guitar,” Koonse says. “He invited me over one day to show me the guitar and I was playing it and just raving about it. It’s one of the finest nylon string guitars I’ve ever played, and it had a pickup in it and it sounded organic with that pickup. It’s very difficult to find a nylon string that feels that way. And he said, ‘It’s yours. I actually bought this for you because I know you have this gig with the Billy Childs Chambers Sextet.’ I was using a lot of nylon strings and I really needed a fine instrument. I had some good instruments but nothing compared to this one. It really upped my game. It was as if the universe provided this to me through Jimmy Wyble.”

During the 1950s, Wyble quilted together an impressive schedule of session work with band performances and his own endeavors.

In 1953, he released The Jimmy Wyble Quintet, an album that offered a more diverse and complex texture than some might expect from the former Western swing musician, although Wyble himself didn’t really consider it jazz. The album featured an accordion, clarinet, percussion, and bass to round out his inventive guitar playing.

By today’s regimented and corporately programmed standards, few musicians cross genres as disparate as country music and jazz. However, in the ’40s and ’50s, it wasn’t as much of a leap as it might seem to a contemporary music fan.

“Many hillbilly guitarists had wide-ranging influences,” writes Charles McGovern in an essay entitled “The Music: The Electric Guitar in the American Century,” collected in The Electric Guitar: A History of an American Icon, edited by André Millard. The author includes Wyble in a group of musicians who were all “legends in Nashville and West Coast studios” and were “as much at home with jazz, swing, and even bebop tunes as they were with fiddle tunes.”

Wyble himself probably didn’t bother with strict genre demarcations, instead preferring to simply appreciate good guitar.

“He kept saying to me, ‘You’ve got to keep an open mind to everything, listen to everything,’” recalls student and platinum selling guitarist Steve Lukather. “He said, ‘Eventually, it’s all going to rub off and you’ll end up with a style of your own.’”

Hallmarks of Wyble’s Style: "Jigsaw"

By David Oakes

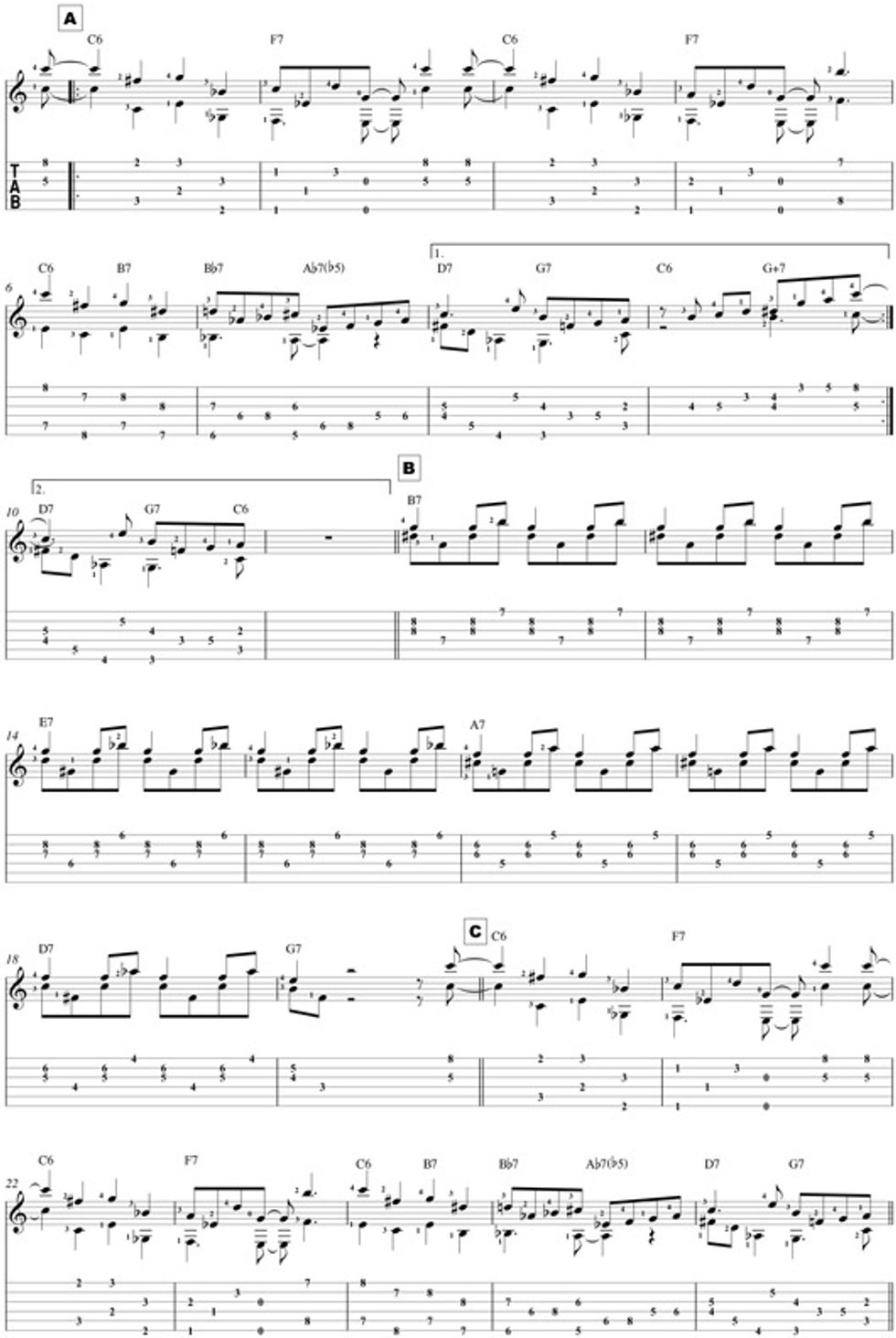

“Jigsaw” is another great composition by Jimmy Wyble. As with many of his etudes, Jimmy recorded this work several different times. The first recording was in 1977, as you hear it here in this transcription, as a trio. The second recording came shortly thereafter from the Etudes record where Jimmy made a solo work out of this piece. He then added the number 23 to the title as in “Etude 21 and 22” as well as moving the title “Jigsaw” down to a subtitle. That version is published in the book The Art of Two-Line Improvisation. When Jimmy recorded the solo version, he added a rubato introduction and filled it in a bit more because he didn’t have the rhythm section. He also recorded it slightly slower and added a different melody on the bridge. This version is recorded at a burning tempo and has several improvised choruses.

Right- and Left-Hand Fingerings

The head to the song is very challenging

to play at the tempo of the recording. The

secret is in the right-hand fingerings. If you

are unsure of the right-hand fingerings,

they are spelled out in The Art of Two-Line

Improvisation, published by Mel Bay. If you

are familiar with that version, take some

time to study those fingerings. However,

my fingerings have evolved as I have been

editing other transcriptions and also had the

chance to learn directly from Jimmy. I like

the way the left-hand fingerings are laid out

in this transcription better than the version

in the book. This version also adds a few

more notes in the low register that gives the

song a fuller sound. Jimmy would probably

have said that he likes both versions. He did

explain that “Jigsaw” was an effort to use

the Van Eps right-hand fingering “team”

concept. He was referring to the team concept

of alternating p and m and then i and a

on any double-stop lines. If you look at measures

1, 3, and 5, he is alternating his fingers

this way in the right hand on those two-note

lines. Most guitarists would use their thumb

exclusively on the bass line but that is not

the way this was intended or recorded.

The Improvised Solo

Even though the solos sound like they are

being played with a pick, Jimmy assured

me that this record was recorded entirely

fingerstyle. Jimmy alternated the thumb and

index finger all the way through this solo.

One exception would be the picked triplets.

Jimmy often use a right-hand fingering of

p–m–i for those kinds of figures. I would use

that fingering on the triplets in measures

38 in the solo section. It will take some

practice to get the tempo of the recording.

Take advantage of any and all places to add

legatos and slides to keep it swinging. Jimmy

would never want you to copy this as much

as he would want you to improve on it.

Jimmy went old-school on this solo, playing more in a tonal center than on the changes. He primarily used a C Mixolydian mode with an added %3 to get a bluesy sound on the A sections. He also used some chromatic approaches to strong chord tones. On the bridge, he tended to play more on the changes. This solo takes me back to Charlie Christian and Lester Young, where we would hear bebop musicians of that period improvise in a very similar way over fast rhythm changes. This solo really swings as well.

I spoke to Jimmy several months before his passing about this tune and he remembered several things about the solo. First he said that he was scared to death when he recorded this song and he remembers wanting to play something in the last bridge, but in his words “I chickened out!” I told him that if it was any consolation, the space that he left sounded good as well. I remember that same idea from the recording “Two Lines For Barney.”

Chef Boyardee

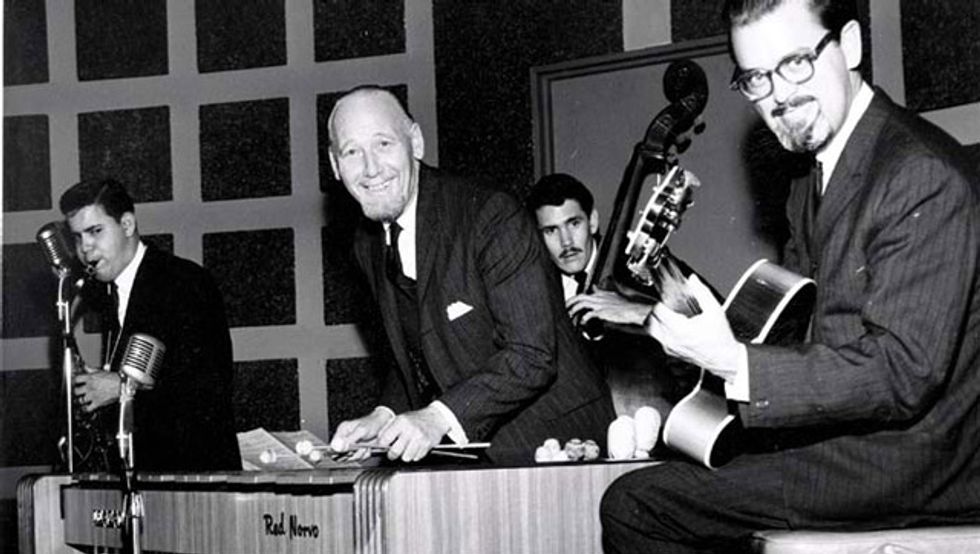

In 1956, Wyble joined Red Norvo’s group.

Known as “Mr. Swing,” the vibraphone and

xylophone player was one of the first to prove

that mallet instruments could provide viable

lead tones for jazz music. His band’s history

includes an impressive list of guitar players,

including Tal Farlow, Jimmy Raney, and Bill

Dillard. Wyble stayed with Norvo until 1965,

a tenure that included stints backing up the

Chairman of the Board himself, captured on

the concert release Frank Sinatra with the Red

Norvo Quintet: Live in Australia, 1959.

During this period, Wyble also performed with the legendary king of swing, Benny Goodman. A notorious stickler and harddriving bandleader, Goodman appreciated Wyble’s work ethic and blue-collar approach. Wyble told interviewer Jim Carlton that his standard routine was to arrive at rehearsal two hours early to practice on his own. He would inevitably bump into Goodman who acknowledged the guitar player’s extra effort with a nice bonus at the end of a tour.

“He worked with Benny Goodman for 12 years,” says David Oakes, music educator and author of Music Reading for the Guitar and Classical and Fingerstyle Guitar Techniques. Oakes maintains an extensive repository of Wyble information on his website [davidoakesguitar.com], including lessons transcribed from the master’s lectures. “That’s unheard of,” Oakes continues. “Benny Goodman probably fired more musicians than any other bandleader in the history of big band. He was notorious for firing people for making mistakes. Jimmy Wyble never got fired from him. As a matter of fact, when Benny Goodman was getting close to the end of his life, one of the people he wanted to call and speak with again was Jimmy.”

Film scores and television soundtracks also vied for Wyble’s attention in this time period. His discography included work on 1958’s Kings Go Forth, 1960’s Ocean’s Eleven, and 1969’s Wild Bunch, among others.

Wyble ultimately left Norvo and Goodman’s groups to settle in Los Angeles and concentrate on session work, teaching, and exploring new directions in his guitar playing. It is perhaps this period of his career that is most influential and important. Counted amongst his students are the aforementioned Koonse, Lukather, and Jacobs, as well as Howard Alden, Howard Roberts, and many others. They recall Wyble as being generous, patient, and inviting to his pupils while also stressing the importance of fundamentals.

“He was so humble from the very first moment I met him when I was 14 years old,” recalls Lukather. “I couldn’t read a note and he was like, ‘Okay.’ Here I was this kid who could play all this stuff because I was pretty good for my age, but I couldn’t read at all. Jimmy was incredibly patient. I played for him and he saw I could play all the rock ’n’ roll stuff and I had some sort of natural ability. He goes, ‘But you know, you’re going to have to break it down to nothing. You’re going to be very frustrated trying to learn how to read music and play ‘Mary Had a Little Lamb’ because that’s about the speed you’re reading at.’ I was very raw and he molded me and turned me onto a lot of stuff I wasn’t aware of.”

When Sid Jacobs first met Wyble, he wept with amazement and joy at what he witnessed.

“We met at a music store and he was already elderly and his hands were shaking,” Jacobs says. “But when he started to play, my God, what came out—it was only things I had dreamed of. Literally I had dreamed once of seeing someone improvise counterpoint, and this was a déjà vu moment and tears came to my eyes. I was stunned at what I was watching.”

In 1977, Wyble released Jimmy Wyble & Love Brothers, an album that demonstrated his increasingly matured and unique sounds and styling.

“He had 40 years of recordings and at the very beginning, he was sounding like Charlie Christian,” says Oakes. “And then when he was in the studios and doing live television he was playing whatever anyone wanted him to play. And then in the ’70s, he started developing his own style, his own sound, his own thing.”

Jimmy Wyble & Love Brothers features two etudes, part of a series of musical pieces that would become the guitar player’s hallmark explorations of contrapuntal concepts and techniques. Those etudes demonstrated unbelievable technique, but Wyble was known to shy away from recognition.

“He just called them ‘noodles,’” remembers Jacobs. “I said, ‘If those are noodles then you’re Chef Boyardee!’”

The ’70s also saw the original release of Wyble’s book The Art of Two-Line Improvisation, which was recently updated and re-released in 2001 with edits and recordings by Oakes. The seminal text melded counterpoint, rhythm, and harmonic concepts based on a sort of mutated major scale into a new way of teaching the guitar that sometimes baffled students, but ultimately opened up new directions in their playing.

“The fingerings can be a bit elusive,” says Jacobs. “But you realize your hands are in recognizable shapes. ‘I recognize these chords.’ But they came at you in two lines so you start to get a little idea on how you can start improvising like that, whereas when you first look at it, you just go, ‘Oh, this looks hard.’ And then when you try to finger it, one or two notes at a time without seeing where you’re going with it, you might get a little confused. But when all the pieces are pulled together, you realize you’ve had a great guitar lesson. At the end of it, once you play them in time, they sound wonderful.”

Picker for Life

Wyble retired from public appearances

and performances in the ’80s to care for

his ailing wife, Lily, who suffered from

muscular dystrophy and was confined to

a wheelchair. The couple married in 1957

and the guitar player frequently referred to

his beloved as “My Lily.”

“He said to me on many occasions, ‘My time is not my own anymore,’” Oakes recalls. During Lily’s illness, Wyble typically refused invitations to go out and see friends. This self-imposed exile from the music business was representative of Wyble’s lifelong habit of deferring the spotlight and basing career decisions on the music, as opposed to ambitions for stardom. That personality trait is at least one contributing factor to Wyble’s lack of a sizable profile today.

“He worked with all these greats like Goodman and Norvo, and he never asked what a gig paid,” Jacobs says. “He just asked himself if he wanted to play the music. I don’t know anybody that can say that.”

“The limelight is not what Jimmy was in this for,” Koonse concurs. “He was really in this for looking inside of himself and unlocking things. Really it was hard to find a trace of any ego because he was selfeffacing to a fault.”

After his wife’s passing in 2006, the guitarist surprised pals by accepting a few invitations, if only to hang out. Jacobs was performing at a Pasadena-area Thai restaurant and convinced his teacher to come along each week. “It got to be our regular Sunday meeting,” he says. Then Jacobs was invited to an out-of-town appearance that conflicted with his regularly scheduled performance.

“I said, ‘Jimmy, while I’m gone, why don’t you cover the gig for me?’” Jacobs remembers. “He said he couldn’t play in front of people. I said, ‘Jimmy, look around, no one’s listening.’ So with a little arm-twisting, he agreed and when I came back, they had offered him his own night, another night, when he realized how much fun it was. He said, ‘Give me your slowest day. If you don’t mind, I’ll sit and play.’ People showed up and, when they met him, they fell in love with him.”

Friends point to those small performances by an elderly man in a small restaurant to a small crowd as perfect representations of Wyble’s caring and humble spirit.

“At the age of 85, after having not played in front of the public for 20 years, Jimmy decides to go out and start playing,” Koonse says. “People started coming out to these performances and the amazing thing is that Jimmy was playing very well. He was a little embarrassed and shy. But that really stands out in my memory, the fact that Jimmy did that and how brave he was. This is a funny aspect—he would stop playing if a woman was at the door. He would go open the door for her and then he’d resume playing. He was very gentle, you know, had a gentlemanly demeanor.”

After his return to public performing, colleagues pushed the teacher to speak at Musicians Institute. Wyble’s classes and lectures were packed not only with aspiring guitar players and students, but even faculty members of the esteemed institution.

“A student might go into that class, and there’d be three or four teachers in the class too,” Oakes says. “The students are looking around seeing their own teachers—maybe their single-string teacher or their reading teacher—studying with Jimmy and learning from him. And they’re going, ‘Gosh, this guy must really be something special’ because that just didn’t happen.”

In spite of his accomplishments and skill on the guitar, he never stopped practicing and devoting untold hours to the instrument. In fact, in the program for Wyble’s memorial service, Steve Kinigstein writes that Wyble stopped performing live after the short run of gigs in his ’80s because it “was eating into his practice time.”

As Wyble’s health declined, he spent time in and out of the hospital. But even in pain and nearing the end, his spirit affected the guitar players who admired him.

“I hate going to the hospital,” Jacobs says. “I hate visiting people at the hospital. But with Jimmy, his vibe was so friendly and kind and generous that you just wanted to be around him. One day I’m there and Dave Koonse is there, Phil Upchurch, Tim May, and he was so friendly. The nurse came in and Jimmy said, ‘I want you to meet Sid, he is a great guitar player, and this is Tim May, he’s a great guitar player,’ and on and on. The nurse asks, ‘Are all your friends great guitar players?’ We all just looked at each other and laughed. Because it was true.”

Jimmy Wyble died of heart failure on January 16, 2010, at his home in Altadena, California. While guitar players and lovers of fine music can listen to Wyble’s recordings and study his instructional books, the musicians who learned directly from the man are the true possessors of knowledge that genius needn’t be accompanied by selfishness and ego. They know from their interactions with Wyble that grace and humility can inspire a lifetime of dedication to the craft.

“He was magical around students,” Oakes says. “He’s 86 and 18-year-old kids are just crowding around him and he has that ability to bring out the best in people.”

Youtube It

Experience a smorgasbord of Jimmy Wyble’s undeniable chops—from swinging on the silver screen, to Benny Goodman’s big

band, to mind-blowing, contrapuntal picking in a quaint L.A. tea house.

Performing with Red Norvo

in a scene from the 1958

film Screaming Mimi

directed by Gerd Oswald.

Performing with Benny

Goodman in 1960.

Performing a mixture of

his etudes at a Pasadena tea

house in 2007.

Performing “The Duke” and

other noodles in the same

Pasadena tea house in 2007.

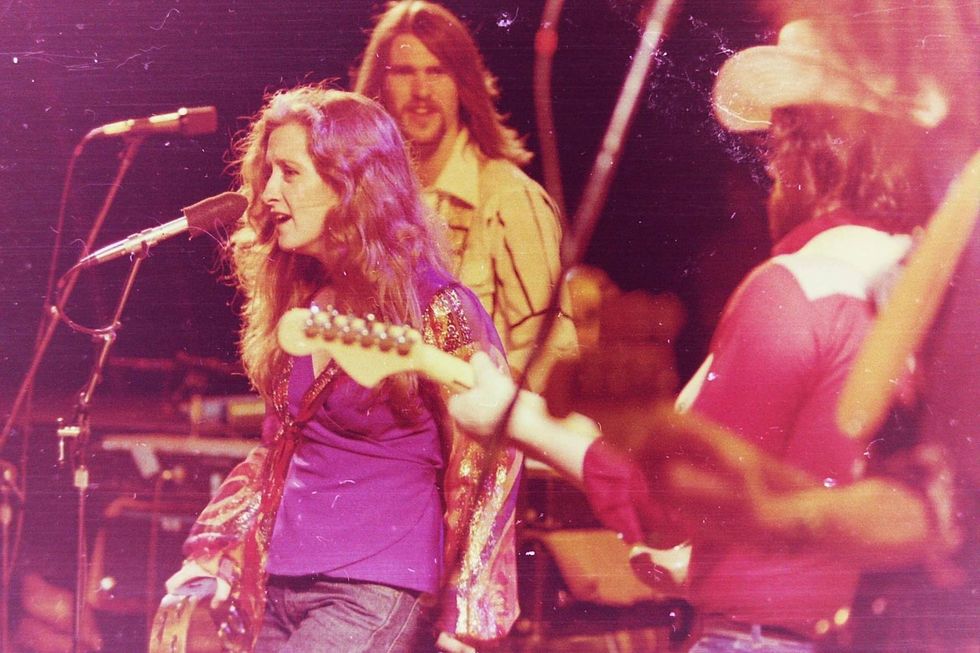

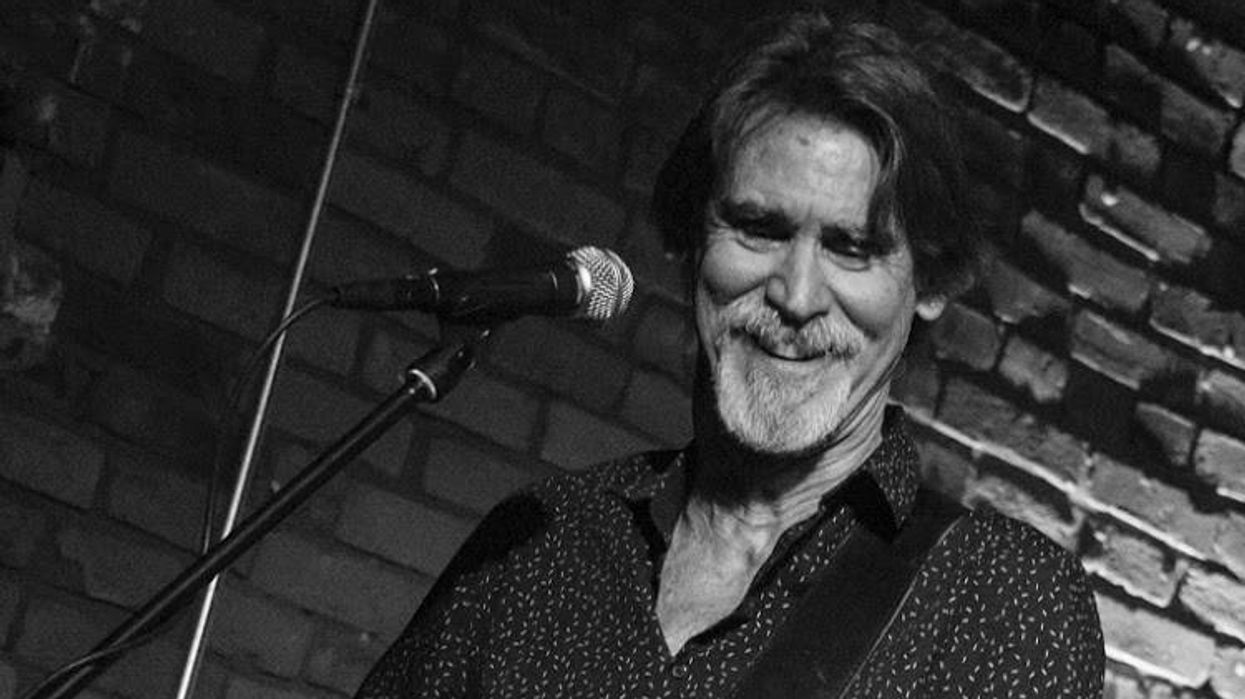

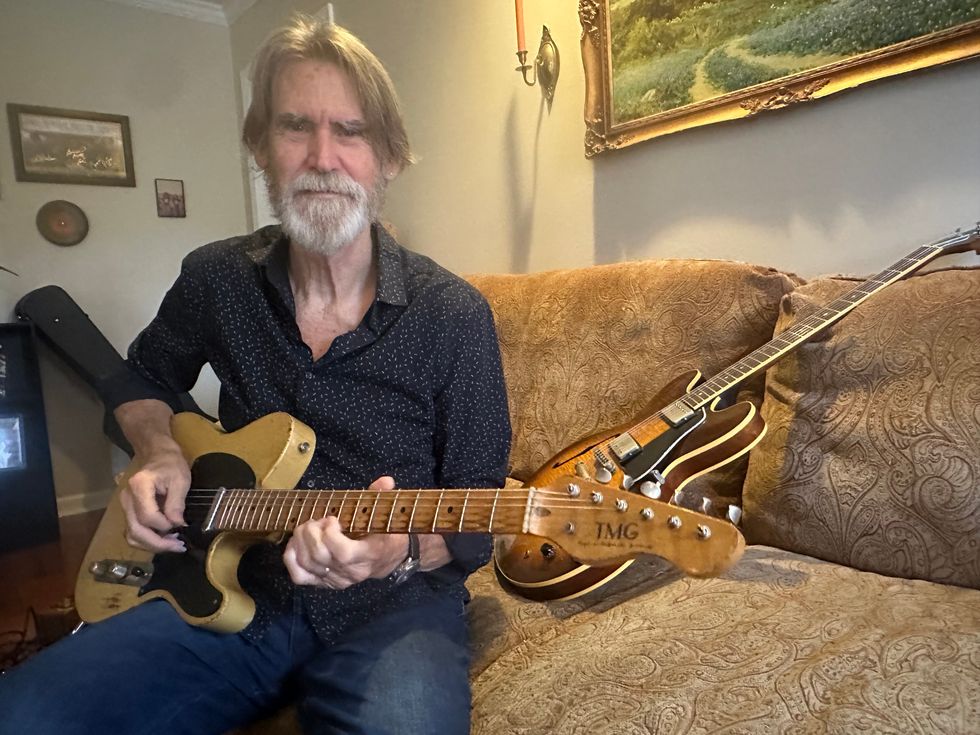

Will McFarlane keeps a Deluxe Memory Man in line with a Princeton—his rig for noodling on the couch at home.Ted Drozdowski

Will McFarlane keeps a Deluxe Memory Man in line with a Princeton—his rig for noodling on the couch at home.Ted Drozdowski