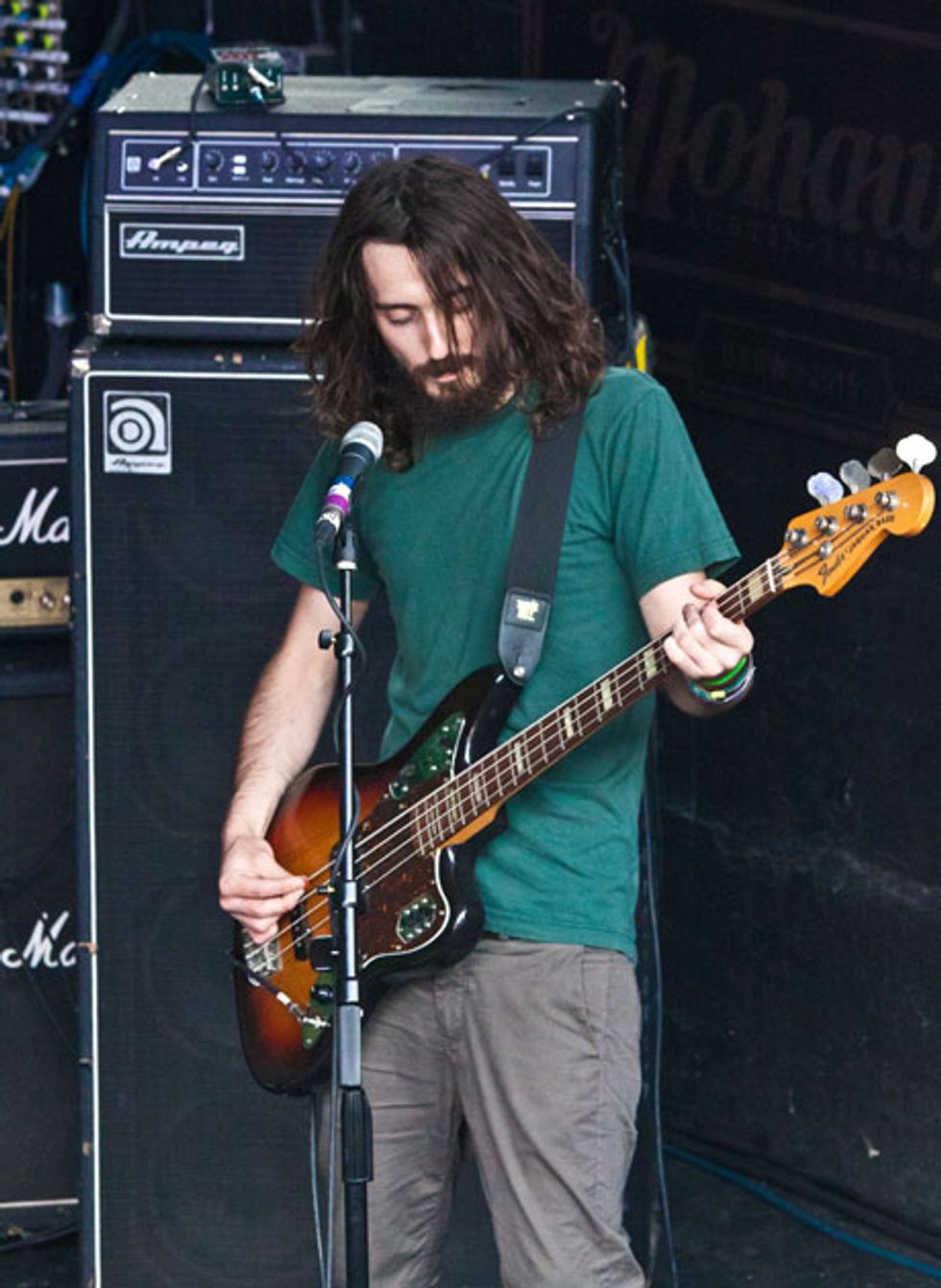

Bones Sloane, an Australian bassist backing Courtney Barnett, spent most of Wednesday afternoon at the Mohawk in Austin slamming against his Fender Jag bass.

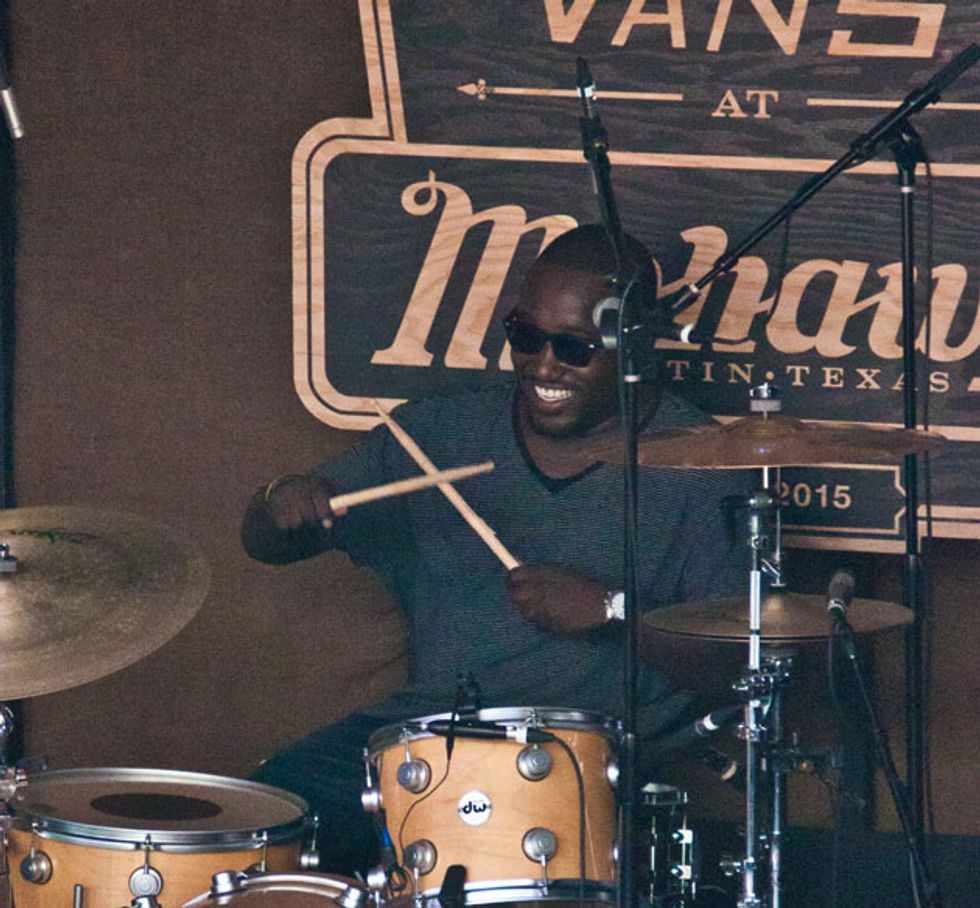

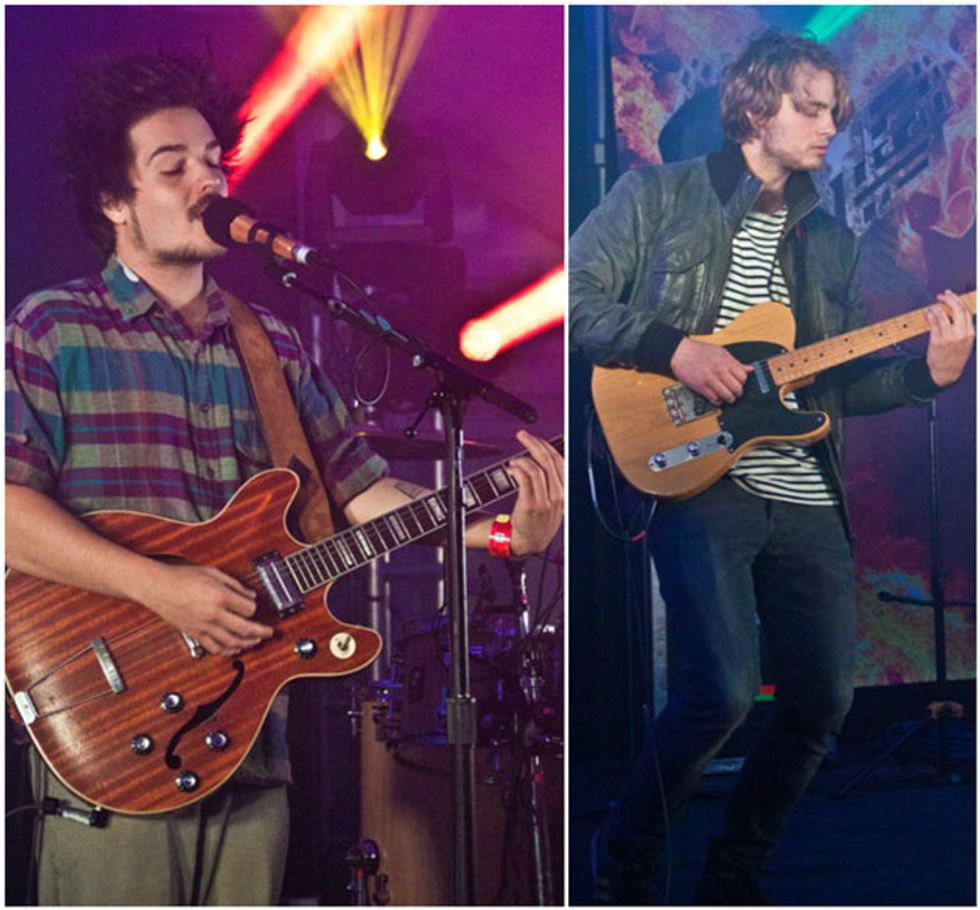

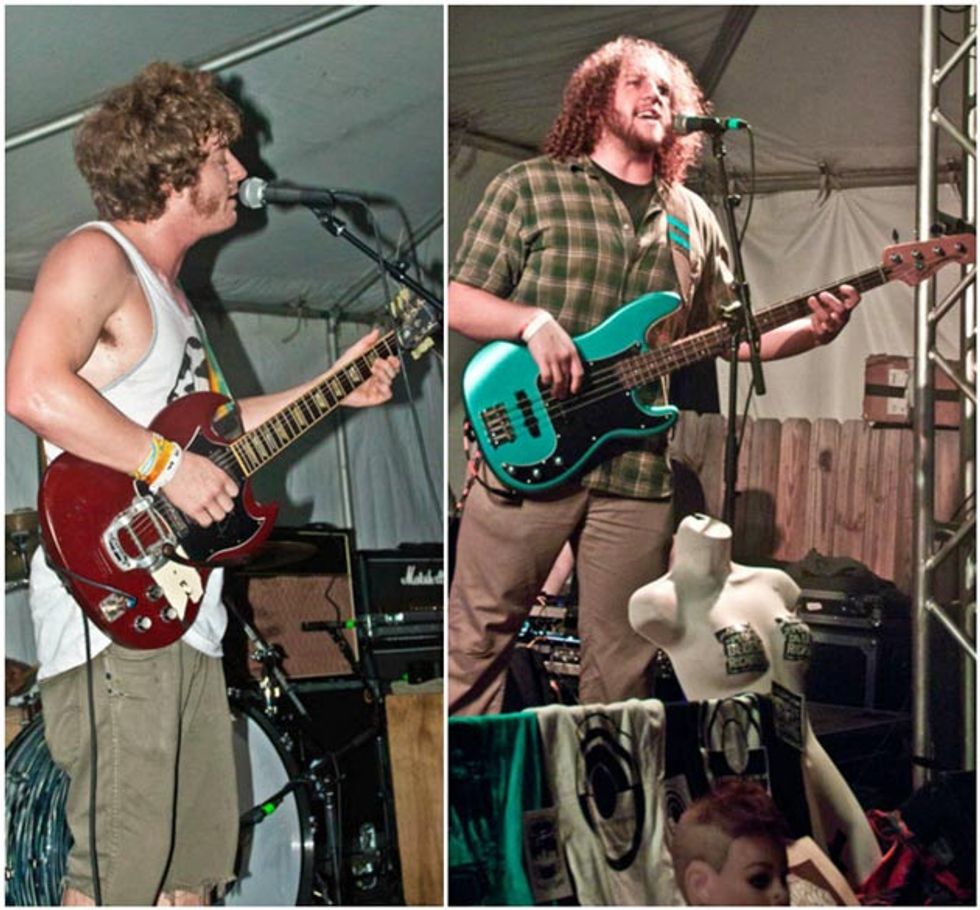

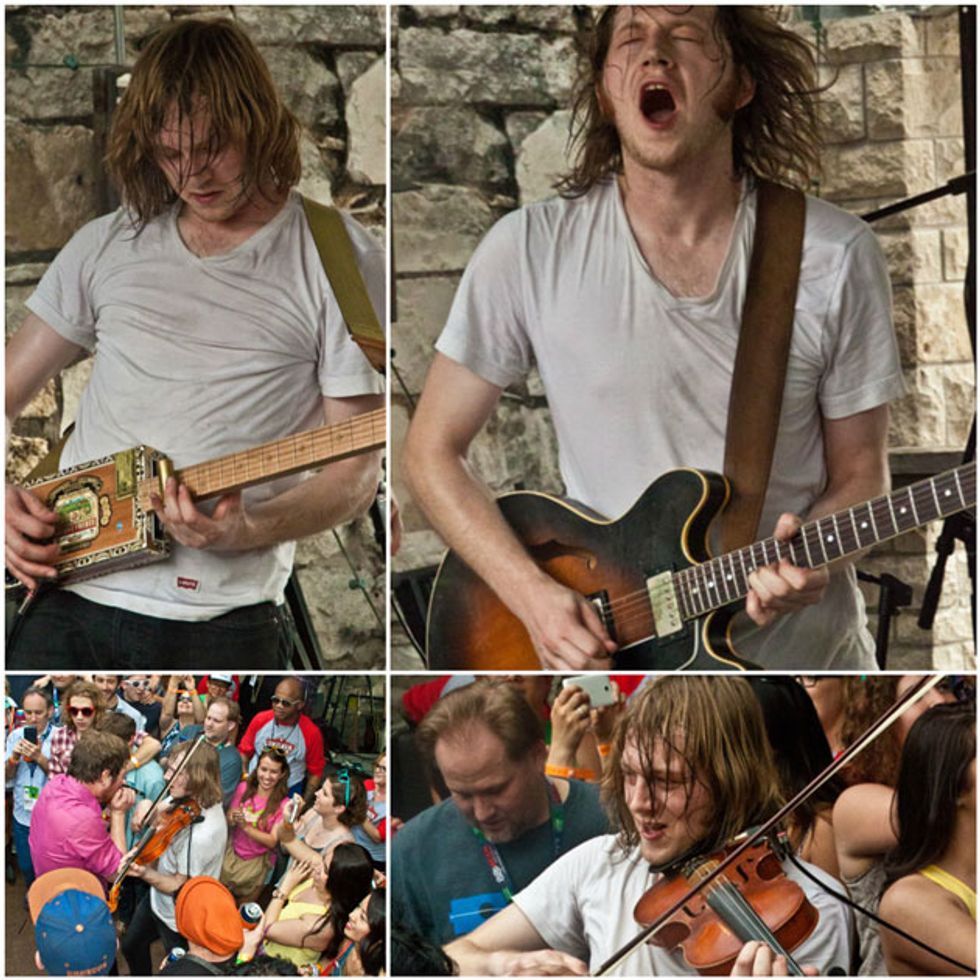

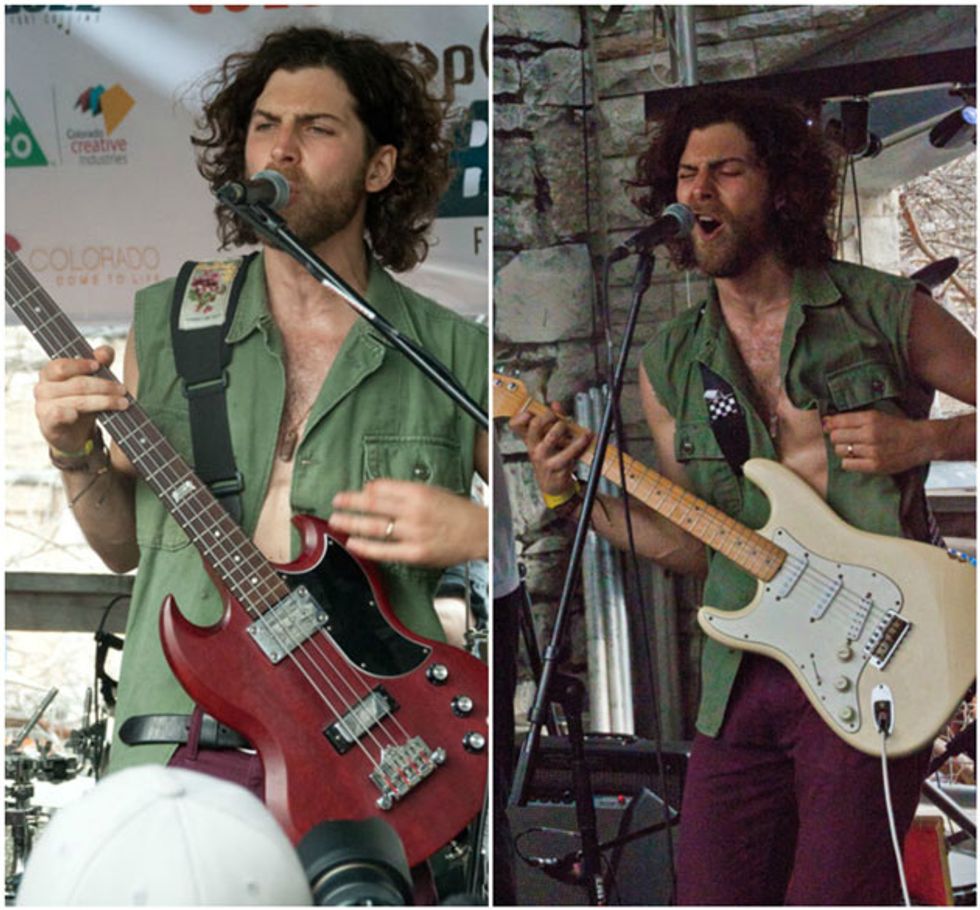

2015 marks South by Southwest’s 28th year as a destination festival in Austin’s beautiful neighborhoods like South Congress, East Austin, and downtown along 5th and 6th Streets. Since its inception, SXSW has tried to serve all music fans with a healthy dose of underground and unsigned acts representing nearly every musical genre imaginable. This year was no different with over 2,200 acts that descended upon the Lone Star State’s capital for five days and nights. Premier Guitar had boots on the ground and here is a fraction of the guitar-centric highlights from the event.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)