San Francisco-based photographer Jay Blakesberg has been documenting the growing improvisational rock scene long before the “jam-band” moniker became popular. Blakesberg’s latest book, Guitars That Jam, focuses on a cross-generational group of musicians and the tools that fuel their exploratory solos and wildly interesting collaborations. Admittedly, the “jam” label gets stretched a bit—we’re looking at you Satriani—but the stalwarts are well represented with insights from Phish’s Trey Anastasio and Mike Gordon, the Grateful Dead’s Phil Lesh and Bob Weir, and members of moe., String Cheese Incident, Widespread Panic, and the Tedeschi Trucks Band.

Rarely does a photographer have the ability and access to capture how a scene evolves more than Blakesberg. His images have graced countless magazine covers and albums while offering a unique perspective that fans don’t often see. For more than 30 years he has captured the essence of improvisational music. In this exclusive excerpt, we take a look at five artists that live comfortable within the community but also do what they can to expand it.—Jason Shadrick

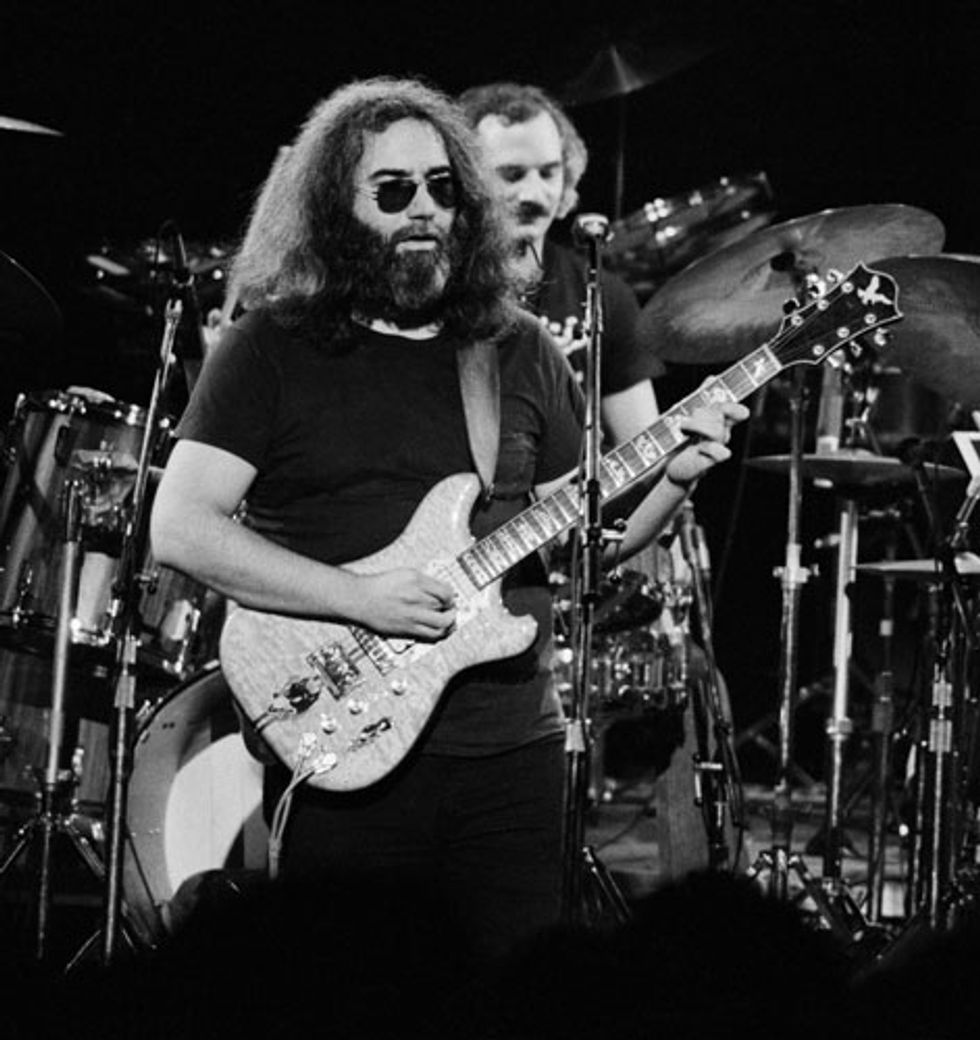

Jerry Garcia's 1973 D. Irwin, Custom “Wolf”

If Tom Anderson’s recollection is correct, at the beginning of the Wake of the Flood sessions Garcia was presented with the custom guitar that would become his primary axe for the next couple of years (and intermittently for many more years). Garcia’s new axe had been crafted by a luthier named Doug Irwin, who, Rick Turner says, “came to work with me when we set up the chicken-shack factory [in Cotati]. He trained with me and eventually started making the guitars for Garcia and then split off and did his thing.”

Rick Turner hired [Irwin] for a half-time job at Alembic; he spent a year or more there, learning the ropes from Turner and Frank Fuller and devoting his free time to building his own electric guitar. One day, toward the end of 1972, Garcia was in Alembic’s Brady Street store and spied the first guitar Irwin had made for Alembic. “He bought the guitar right on the spot [for $850], and asked me to make him another guitar,” Irwin recalled in an interview.

“So I built the next guitar for him,” Irwin recalled in the same interview, “which I had actually started building at the time he ordered it; it was made out of purpleheart [also known as amaranth, a South American wood] and curly maple. It had an ebony fingerboard and mother-of-pearl inlays. This is the one that became the ‘Wolf.’”

Grateful Dead, Capitol Theater, Passaic, NJ, November 24, 1978

The guitar didn’t receive its “Wolf” moniker until later. Garcia had put a decal of a bloodthirsty cartoon wolf below the tailpiece, and after bringing it in to Irwin for refinishing between tours one year, “I knew the decal was going to be gone, so I just redid the wolf as an inlay,” Irwin said. “In fact,” Garcia recalled in 1978, “it was a week or so before I even noticed what he had done!” Garcia first played the Irwin guitar on the October ’73 tour.

Beginning with the fall 1977 tour, Garcia stopped playing Travis Bean guitars and went back to the Irwin “Wolf,” which a little earlier had been retooled to include the effect loop and unity-gain buffer that had worked so well in the TB-500. Garcia never expressed any particular dissatisfaction with the Beans; perhaps he just liked the woodier feel of the Irwin axe. It was at this time, too, that Doug Irwin inlaid the “Big Bad Wolf” (as Jerry called it) on the spot where an identical sticker had been.—Excerpted from Grateful Dead Gear, by Blair Jackson

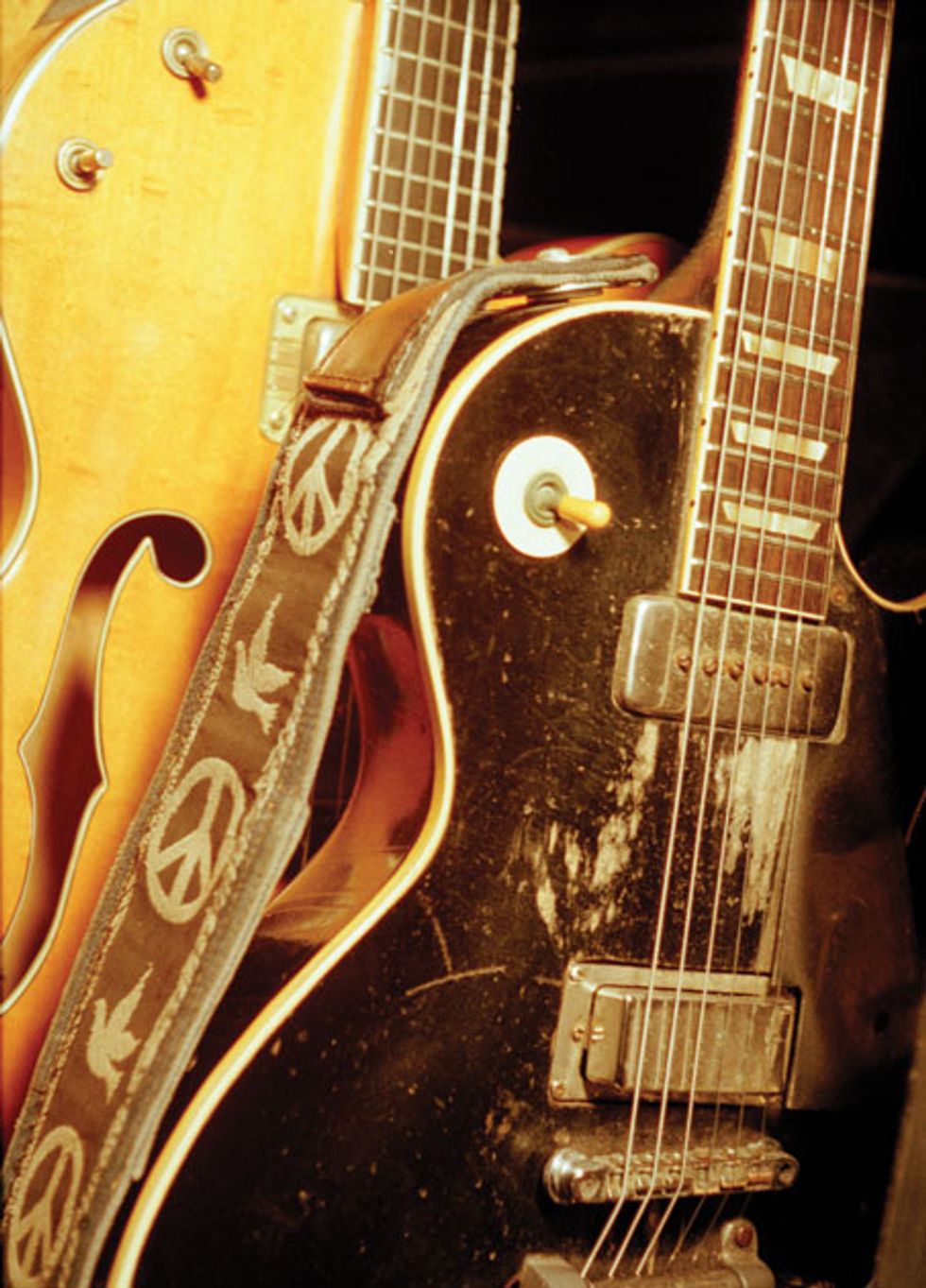

Neil Young's 1953 Gibson Les Paul

This is Neil’s main electric guitar. It’s a 1953 Les Paul goldtop that’s been painted black—in 1953 they only made gold Les Pauls. It’s got a mahogany neck and a mahogany back with a maple cap on the top.

Neil Young & Crazy Horse, Key Arena, Seattle, WA, November 10, 2012

Originally, the ’53 Les Pauls came with what’s called a “trapeze bridge.” The strings came from underneath the bridge because the neck wasn’t tipped back far enough in ’52 and ’53, which made the guitar pretty much unusable. In ’54, they got rid of that bridge because they tipped the neck back to its present position, but the thing with having less of a neck angle is that you can have a lower bridge, which works much better for a Bigsby, which Neil has used extensively. So this has a Gibson Tune-o-matic bridge on it, and it has a Bigsby B7 vibrato on it.

Originally, this guitar was made with two P-90 single-coil pickups. In the early ’70s, Neil took it to a luthier to have some modifications done. When he came back to pick up the guitar, they’d gone out of business. Neil tracked down the guitar, but the bridge pickup was gone. So they put in a late ’50s Gretsch pickup, a DeArmond pickup with adjustable magnets for the poles. It’s a special Gretsch pickup, and it’s only in the bridge position. The neck pickup was still the P-90, but they put a silver cover on it. I started working for Neil in ’73, so this was the condition I found the guitar in, with the DeArmond pickup and the Bigsby and the Tune-o-matic.

After a year I put a Gibson Firebird pickup—a small, two-coil humbucking pickup—in the bridge position. The Firebird is a very unusual pickup noted for its particularly bright tone. This particular pickup is remarkably microphonic. If you tap on the guitar, you can hear it. Neil has even talked into it, screamed into it, and you can hear it coming out of his amplifier. It’s that microphonic, which contributes to the unique sound he gets.

I found the remnants of a switch in the middle of the four knobs. No switch was there, and what it did I don’t know. So, what I ended up doing was put a miniswitch in that hole and routed the bridge pickup directly to the jack, bypassing both the volume and the tone control on that pickup. After I did that, Neil said, “It’s like it goes to 11 now.” You’d be surprised how much energy and tone gets absorbed by the volume and tone control. It’s a remarkable guitar. It has extremely low action and plays really great. —Excerpted from interview with guitar tech Larry Cragg

Mike Gordon's 2014 Visionary Instruments Custom Moiré Bass

This instrument is one of a kind. It was finished for me just in time for my March 2014 tour, and Ben Lewry of Visionary Instruments flew out to some of our locations to make some final tweaks. The 3-D light patterns were my idea, and they make for some great photographs—especially Jay Blakesberg’s! There’s also a 3-D effect you can only see in person.

The Fillmore, San Francisco, CA, March 18, 2014

When I picked up this instrument, I wanted to transcend the typical jam-band stage set by finding new themes that could encompass the entire concert experience from visual to auditory to interactive. I started noticing moiré patterns everywhere, and an exhibit by artist Annica Cuppetelli inspired the idea of an interactive use of these patterns. Ben Lewry had created some instruments for notable people—guitars with LCD screens or robot control knobs, so he was the perfect person to carry out my idea for the invention of a new kind of bass. He appreciated that, in an age steeped in digital projections, this concept is entirely organic—like two screen doors on steroids. It was Ben’s genius that allowed an instrument to wirelessly take lighting cues and to react internally to the notes being played, without any compromise to the tone. Every time you use LED lights there is a pulsation that can put hum into guitar pickups, not to mention the various wireless circuits, and despite that the instrument has a better sound than any bass I’ve ever played!

What’s most significant for me about this instrument is that when I was 5 I wanted to be an inventor. This bass allowed that dream to come to true. I’ve never seen anything like it, other than the guitar version, which was simultaneously made for Scott Murawski.

I’ve had several great moments with this instrument already, but one that stands out occurred when my band was playing “Peel” in Vancouver, and it became a long exploration. I even picked up a bouzouki at one point and then put the moiré bass back on, and then the music took us to some Portuguese hamlet. We had left the bass and guitar lights off, when all of a sudden the lighting designer, Liggy, blasted bright beige (a color only available when beamed from the outside) into the bass, the guitar, and the set pieces, and the jam seemed to scream out to the stratosphere, leaving a trail of beige fire.

I remember lying on the family couch with my first guitar when I was about 12. Every day I had a few minutes of slowly plucking notes and getting into the Zen of the tone decaying, the instrument balanced on my chest. My favorite thing is to pluck (or pick) a note on the moiré bass and feel a little bit of the metal screen after striking the note—it’s a metaphor for the way I’ve taken my career into my own hands; I’ve pushed myself in a new direction unique to me. And really I’ve only scratched the surface! I wasn’t intending a pun, but I can’t really back out of that one.

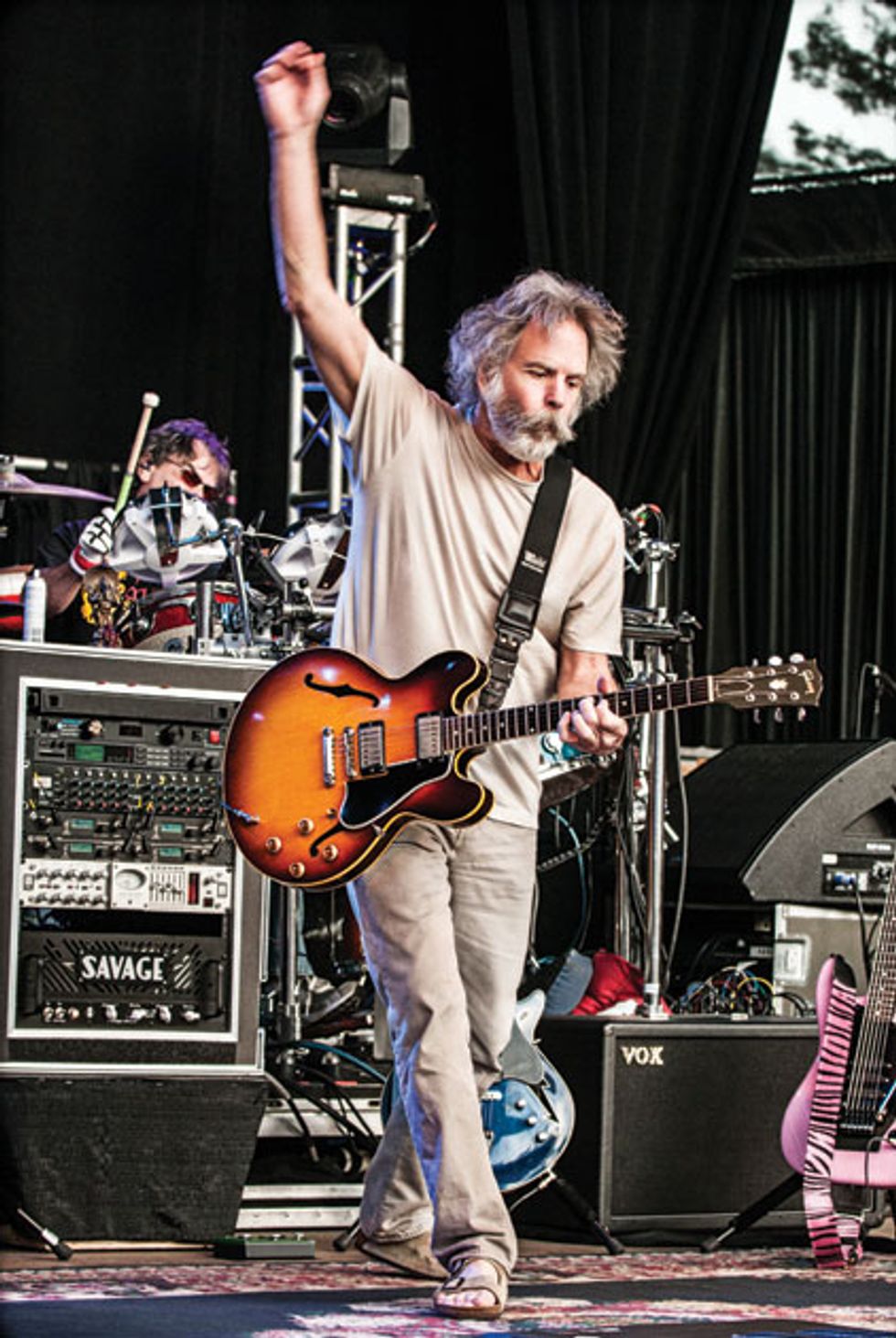

Bob Weir's 1959 Gibson ES-335

It was my first time in Nashville—I think it was around 1970—and I went to

Gruhn Guitars there—great guitar shop. I was just nosing around, playing a few guitars, and one of the guys in there was watching me—and he said, “You ought to look at this guitar.” He pulled it off of a rack, and I played it and fell in love with it. It was 350 bucks. Back then that was a lot of money—it was a couple months’ rent—but I had to have it. It’s worth a couple hundred times that now—it still has all the original parts. It’s pretty much the holy grail of thin-body guitars.

Furthur, Bill Graham Civic Auditorium, San Francisco, CA, December 30, 2011

I was immediately drawn to the feel of it. I also liked the way it sounded, but I loved the feel—loved the neck, which is relatively slim for a Gibson. Sonically I can do just about anything. It’s not going to sound like a single-coil guitar—it’s definitely a Gibson—but that said, it can get bright, real bright. In fact, I generally play it pretty bright. It has wonderful balance. The tone isn’t real tubby. Sometimes Gibsons have a sort of tubby tone, but not so with this particular guitar. And it works well both in the studio and live—it’s good no matter where you plug it in.

Steve Kimock's 1972 Charles LoBue Explorer

I didn’t go after this guitar; this guitar came to me. You could say more than anything that they were both gifts. When I got this, I was playing in a band called the Goodman Brothers. We lived on a farm in Pennsylvania. The whole setup was kind of a commune.

There was more than one band involved in this, and the guitarist in the other band, who was known by the name of M.K., played theatrical hard rock, and he used to throw his guitars a lot and spin them around his body on the strap—lots of guitar throwing. Apparently, Explorers don’t throw well. He got the guitar and didn’t have it long before it was thrown and broken. He repaired the headstock, but realized that the guitar was not very aerodynamic. I had maybe two Stratocasters at the time, and he said, “Hey, you want to trade the Strat for the Explorer?” So that’s how I got it. That was ’74 or ’75. But I didn’t go looking for it, it was one of those “to each according to his needs” commune deals, and it just turned pretty instantly into my main guitar.

Sweetwater Music Hall, Mill Valley, CA, December 15, 2013

I think Charles made four Explorers. The most visible one belongs to Rick Derringer, who did a Guitar Player cover with his LoBue guitar back in ’75. LoBue also made basses. I think there was a lot more visible, iconic use of his basses. He made Gene Simmons’ first axe bass, for example. He also took care of the New York guys. The funk guys, like Alphonso Johnson had a couple of LoBue fretless guitars that he played later on in Weather Report.

LoBue became a friend, and since he passed I’ve been trying to find his guitars and get them under my roof so eventually I can pass them on together. I have three of those Explorers. I don’t know where Derringer’s is. It might be with Gibson still, or it might be in Nashville, or it might have been destroyed in the flood. Nobody knows. But I’m seeking them out, because I loved the dude. Charles was a very special guy. He was in my life for many years.

I think what I like most about the guitar is that it’s been with me through everything. It does whatever I need it to do. It’s a great big dominating-sort-of-thing in the mix. That guitar will eat the room; it’s one of those guitars. You can’t pick it up unless you mean business. It’s like, “Okay, we’re not screwing around here!” Also when I’m picking up this guitar, I’m picking up a lot of stuff, a lot of memories. I’ve got pictures of it from pretty far back, and it was beautiful back in the day. You can see now that it’s pretty beat up, but so am I. We’re aging together, and old friends with gray hair are hard to find.