Since the first Guitar Hero game was released on Playstation2 in 2005 and Rock Band in 2007, the two have combined to sell more than 55 million game units (according to Activision and Harmonix). In that same amount of time, countless guitarists have dismissed the games with varying degrees of spite. And though antiguitar- game sentiment has quieted perceivably in recent years, one lingering question remains: will these plastic-button “guitarists” ever transform into genuine wood-and-steel heroes of the next generation—and what can the game do to make that happen?

Enter the Squier Stratocaster Guitar and Rock Band Controller—the first ever full-size, fully functional guitar that doubles as a game controller. Used with this year’s Rock Band 3 Pro Mode (see sidebar below), the first-ofits- kind hybrid is the only real contender in the battle to bridge the gap between game and guitar. And it puts up a hell of a fight to win the favor of players from both camps.

Rock Band 3’s Pro Mode

This guitar exists because of a new game mode introduced in the latest Rock Band game, and is therefore not compatible with previous versions of the game. Pro Mode breaks out of the previous five-button format to present the entire fretboard across six strings. Currently, Pro Mode is only playable using this Squier or a 102-button plastic Mad Catz Fender Mustang replica controller.

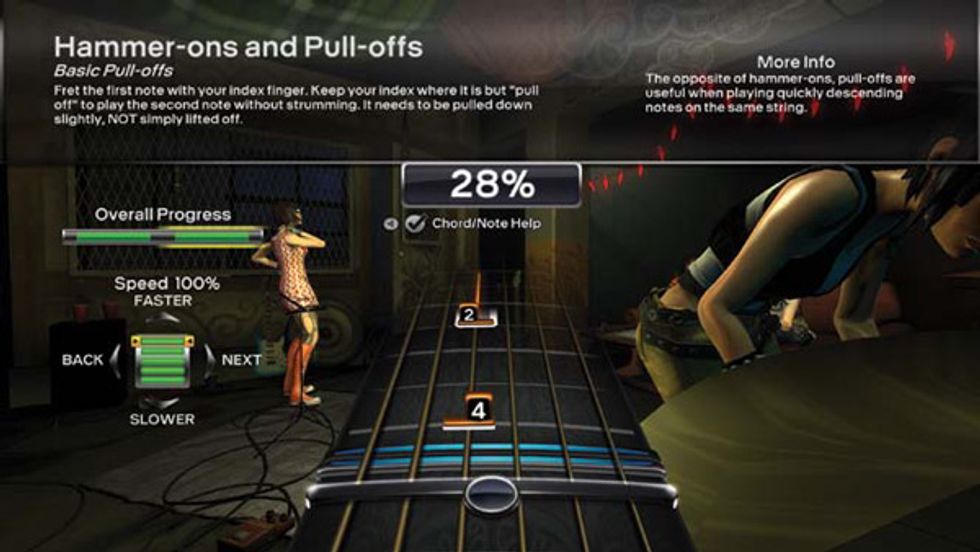

Like the original game, the note “bubbles” come toward you conveyer belt-style, this time with a number attached to indicate the fret. Open strings are noted with a “0” and muted strings with a blue “X.” Chords follow a new convention: the low note shows a fret number, while a note “bubble” stretches across the subsequent strings at different thicknesses on each string to indicate how many frets away from the root that string should be fretted at.

A Guitar that’s a Controller? Or a Controller that’s a Guitar?

Let’s get this out of the way—this is a budget Squier Strat that makes certain concessions as a guitar to live a double life as a video game controller. If you’re looking for a superbly playable, versatile, and toneful instrument, Fender makes plenty of those at different price points. Aside from the electronics, which we’ll get to in a moment, it shares many of the same specs as a Squier Standard Stratocaster: agathis body, maple C-shaped neck, 25.5" scale, 9.5" fretboard radius, 22 medium jumbo frets, and 1.650" nut width.

Currently there’s just one finish option—black polyester. There’s also a single-ply white pickguard, and a six-saddle non-tremolo bridge. A Fender strap is included, but I would’ve liked to see a gig bag as well.

Because of the many special considerations necessary for a guitar that is also a game controller, this Strat has a number of proprietary features. The unique truss rod is adjusted with a mechanism located in the treble side of the neck near the neck joint. In place of the neck pickup, there’s a pop-up string mute that allows the game to better track picking during gameplay (a necessary addition given that the game rarely registered the low strings correctly when unmuted) but which can be popped back into the body for playing sans-game. The guitar also features dual outputs for a standard 5-pin MIDI jack and a standard ¼" output jack. The two can be used simultaneously, meaning you can play through an amp while you’re playing the game—which is entirely unnecessary but completely fun. The MIDI output also makes the guitar useable as a MIDI controller using a standard MIDI cable (included) and your preferred DAW.

The single hex pickup in the bridge is a special design for this instrument, as is the polymer fingerboard, which has embedded position sensors that track extremely well and numbered position markers on both sides of the neck. Nestled in the array of knobs and buttons used for gameplay is a volume control— the only control for the guitar itself. The game controls include a T-shaped directional pad, Start (left arrow) and Select (right arrow) buttons, and four tiny, color-coded buttons that correspond to the four standard game controller buttons. The guitar can be used with Xbox 360, PS3, or Wii, as long as you have the correct Mad Catz MIDI converter (separately by Mad Catz for $39.99). The gaming-related side of the guitar runs on three AA batteries, but battery power is not required for just plugging into an amp and playing.

What’s it All About?

If the point of the guitar is to bridge the gap between gamers and guitarists—to guide a generation of button mashers to the art of music making—putting it to the test with the experienced, gig-tested, guitar playing editors of this magazine exclusively would not suffice. So, we recruited a group of testers that represented just about every category of player that might be interested in a 6-string game controller: a serious gearhead guitarist, a guitar teacher, a hobbyist guitarist, a beginning guitarist and gamer, and hardcore gamers with no guitar experience.

An Experienced Guitarist’s Perspective

If you’re approaching Squier Stratocaster Guitar and Controller as a guitarist looking to have some fun playing Rock Band with the family, you may be disappointed. One tester noted that the polymer fretboard “feels like nails on a chalkboard” when using finger vibrato—which brings us to one of the biggest negatives from a guitarist’s perspective. Because of the way the game operates, any vibrato or bending registers as a wrong note. For an experienced guitarist, it can be difficult to separate what you already know from what the game says you’re supposed to be doing, particularly if you’re a player who plays by ear. On easier levels of difficulty, notes are often omitted and it’s difficult to fight the urge to fill them in based on what you hear. On more difficult settings, what appears on the screen may not jive with the part that you already know, resulting in missed notes, poor scores, and frustration knowing that you can’t follow a game at the same level you can actually play a song.

A Teacher’s Perspective

As a learning tool, the combination of the Strat and Rock Band 3’s Pro Mode is undoubtedly the best option out there for learning guitar through a video game. The mechanics of the game develop dexterity and to acclimate new players to playing strings. It serves as a rudimentary introduction to guitar, though there is an inherent limit to the learning. Techniques like bending, vibrato, and tapping aren’t covered, so at a certain point a student would either stall in technique or graduate to real lessons.

Our guitar teaching tester saw particular potential in the guitar if additional games were released to encourage honing your technique beyond learning the songs included in Rock Band 3. As it stands, someone who is interested in picking up guitar for the first time may be better served taking actual lessons to develop their technique. “Is it better than getting a real guitar and teaching yourself? No,” noted our guitar teacher tester. However, if someone is more psyched about playing a game than playing guitar, this is an excellent transition into learning.

A Beginner Guitarist and

Gamer’s Perspective

A Beginner Guitarist and

Gamer’s PerspectivePerhaps the group most interested in the Squier Stratocaster Guitar and Controller is players—particularly younger ones—who already play both the video games and some guitar. In a culture of instant gratification, the game delivers in ways that books and lessons can’t. It has built-in motivators to keep players on task with training modes for technique and for sections of songs. Each training section runs in an unending loop as you try to score 100 percent to move onto the next portion. This appealed to our tester, who said, “I liked that the game has training that keeps making you do certain notes until you get them down.” Needless to say, getting a 13-year-old to appreciate practice is an impressive feat—made possible in this case part by the gratification of a “perfect score” that’s so ingrained into video gamers.

Learning songs on the guitar was one of our young tester’s favorite parts of the combination, but he also recognized that it can be more difficult at times than learning from TAB books. While you can incessantly loop sections of songs, the loops are predetermined and zeroing in on a particularly difficult part of the section is impossible. Still, the tester loved the guitar and experience— and didn’t want to give it back.

A Gamer’s Perspective

The category of people who would stand to benefit most from the Squier are gamers who have maxed out their abilities on the games, but don’t have the interest or motivation to start guitar lessons on their own. Our strictly gaming testers found the guitar and game combination intriguing, difficult, and motivating. If you’re just starting out, learning how to navigate the fretboard and strings through the tutorials is a somewhat lengthy process, but our testers reported that time flew by when playing it. The tutorials lead smoothly to the next without ever jumping up to a difficulty level that caused them to abandon the cause, and each ends with a song to keep the gaming aspect intact. “Playing all the way through the first song was awesome,” noted one tester. “The tips of my fingers were sore, but I felt like I really accomplished something.”

Guitar Hero and Rock Band experts expecting to be able to jump right in will encounter difficulty— testers who had done well on Expert and Hard on the regular game found themselves struggling through the Easy level in Pro Mode with the Squier. It’s a fitting evolution for the player that has mastered the game. It fulfills the next challenge, and opens another seemingly limitless world of game play (particularly with downloadable Pro Mode songs—not cheap at $2.99 a pop), while imparting a real feeling of accomplishment. Even testers with no existing desire to play guitar were inclined to think about it as a more desirable pursuit—and that is what it’s all about.

The Verdict

The VerdictGuitar games have been controversial to guitarists since they first hit the market. And all along people have been asking for the link that will turn gamers into guitarists. The Squier by Fender Stratocaster Guitar and Controller with Rock Band 3 might well be that link. It’s not perfect.

Occasionally the strums aren’t picked up by the game, and guitarists accustomed to higher quality instruments might have some reservations about the construction. And the game alone isn’t going to make anyone shred like Yngwie. However, it certainly feels like the beginning of something. Perhaps some years down the road when learning guitar this way is commonplace, this instrument will have marked a critical stepping-off point.

Though it’s easy to consider the notion of learning guitar motivated by gaming success less than pure and noble, stop and think of why you started playing. Was it for the art? Or was it to get girls? While it would be nice if every pre-teen girl and boy with a passion for music picked up the guitar and practiced day in and day out, today’s reality—riddled with distractions like texting and Twitter—demands something more motivating, and the music scene isn’t always enough. There are fewer Beatles, Jimis, or Eddie Van Halens leading kids to guitar like the pied piper. If it takes a game for the next Eddie or Slash to pick up a guitar in this day and age, so be it. At least now there’s a tangible, affordable, and appealing link to push them to the next level.

Buy if...

you or someone you know is serious about taking guitar gaming to a new level and starting a real guitar journey.

Skip if...

you’re an experienced guitarist looking to have some fun—try Rock Band’s drums or vocals instead!

Rating...

MSRP $280 - Squier by Fender - squierguitars.com |