Benson’s latest release, the 12-song Guitar Man, showcases more 6-string slinging than many of his previous releases. “That title was a way to let people know there would be more guitar on this record than they’ve been hearing in the recent past,” says Benson. Among the album’s highlights are tributes to two of the jazz icon’s guitar idols. “Tequila” tips the hat to Wes Montgomery, while “I Want to Hold Your Hand” is a nod to Grant Green rather than the Beatles. But though Guitar Man features plenty of guitar, it’s not quite as over-the-top as the pyrotechnic-laden classics from 1974’s Bad Benson. This latest effort is more refined and has about just as much guitar as a successful commercial album would allow, as evidenced by the fact that Guitar Man reached No. 1 on the Billboard jazz charts a few weeks after its release.

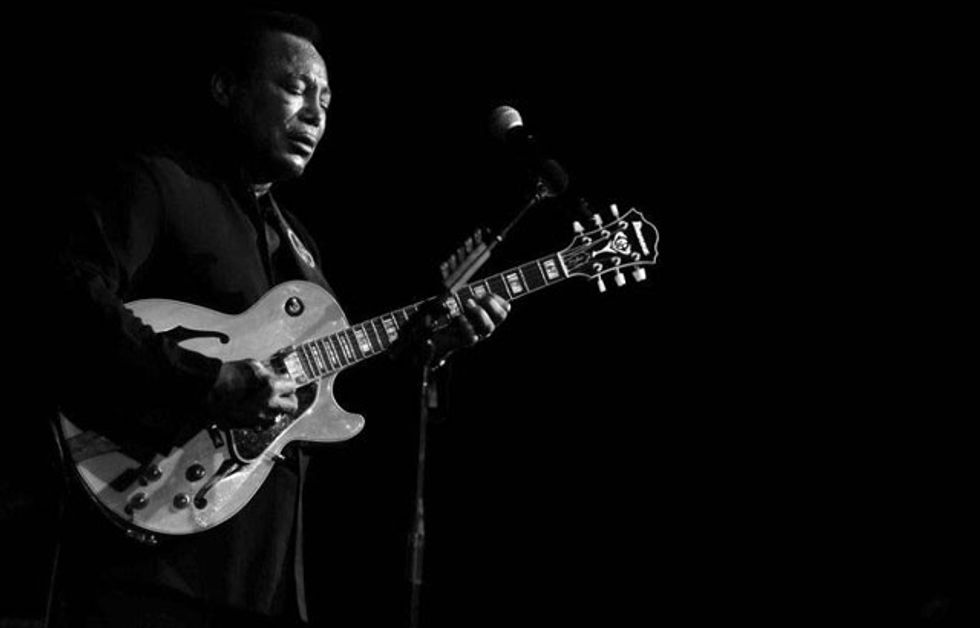

Photo courtesy William “Billy” Heaslip

Photo courtesy William “Billy” HeaslipWe caught up with the smooth operator to discuss the new album, his gear, and his unique picking technique—which has long been a hot topic among the hordes of Benson wannabes.

You played a lot of acoustic

guitar on Guitar Man.

Yeah, we used two different kinds

of acoustics—a Yamaha and a

Cordoba. They aren’t very expensive,

but they sounded good.

Did you use any of your

signature electrics?

Oh yeah, definitely. I used

the Ibanez GB30 and also a

D’Angelico that I had in the

closet. I only take that out on

special occasions. I got a lot of

my hit records with that guitar.

Do you roll the tone knob

down or do you keep it all

the way up?

I have both the tone and volume

controls basically all the

way up. Something happens to

the tone when I back up off the

volume—I like to feel the bite

of the guitar. Y’know, feel all

the openness.

Some jazz cats feel like a lot

of that bite has to do with

strings. Are you pretty particular

about yours?

If I’m on the road, I like to use

.012s. If I’m recording, I like to

use .014s—I can hear more and

dig in more with the .014s. On

the road, I can’t really hear all

that because it goes past me and

out into the audience.

Can you play as fast on the

.014s as you do on the .012s?

Yeah, I think so. I never

thought about that. I better

put that to the test before I say

“yes.” [Laughs.]

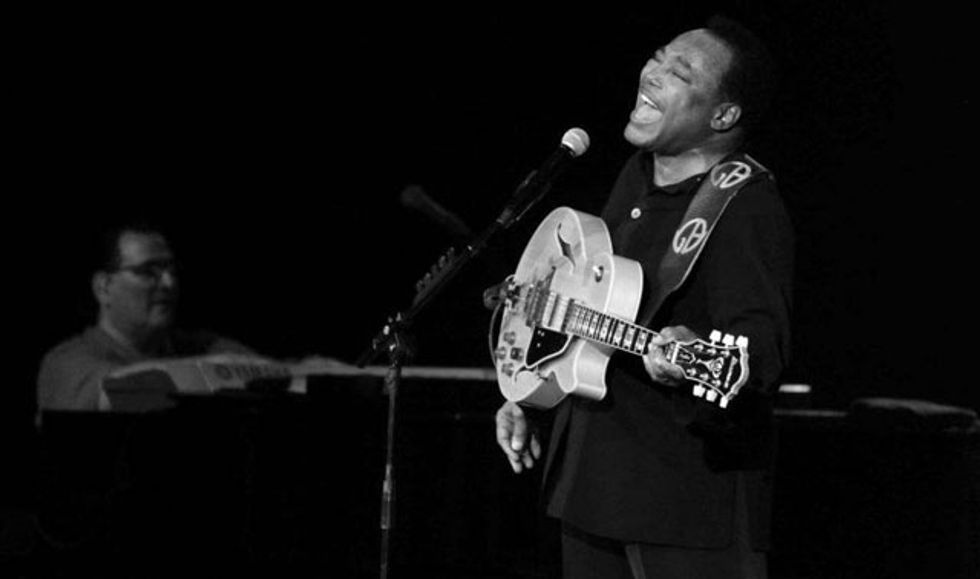

Photo by Jerry L. Neff

Photo by Jerry L. NeffHave you tried any other

Ibanez jazz guitars, like the

Pat Metheny model?

I’ve tried a couple of those and

some of them were good, but

mine is designed with my needs

in mind. I don’t like feedback,

and I don’t like thin sounds. I

want a full sound but I don’t

want to worry about muting

the strings because they’re

feeding back. My GB10 is

unique because it has a smaller

body, which takes care of a lot

of the feedback issues.

You recently auctioned off

some instruments you owned

that originally belonged to

some pretty famous people.

Yes. Pat Metheny bought Wes

Montgomery’s L5 at auction. I

didn’t know it until I ran into

him in Europe and he said,

“George, I got the Wes guitar.”

And I’m happy, because now

I know it’s in good hands.

I worried about it when I

auctioned it off. Also, Grant

Green’s guitar. That’s one of

the best-sounding instruments

I’ve ever heard, but it was in

my closet and I was afraid the

termites were going to eat it up.

Considering the times being

what they were, we did very

well and got a lot of money.

Do you ever play with distortion?

I was thinking about trying

some things out with distortion,

just to see what happens.

I did it with Billy Cobham

and George Duke one day, and

they were shocked. They had a

guitar player in their band, and

I didn’t want to mess with his

pedals. He said, “Just press that

one over there for volume.” I

hit that button and it was like

a rocket ship, man! I started

playing all this stuff and those

cats went berserk. They said,

“George I didn’t know you

could play like that.”

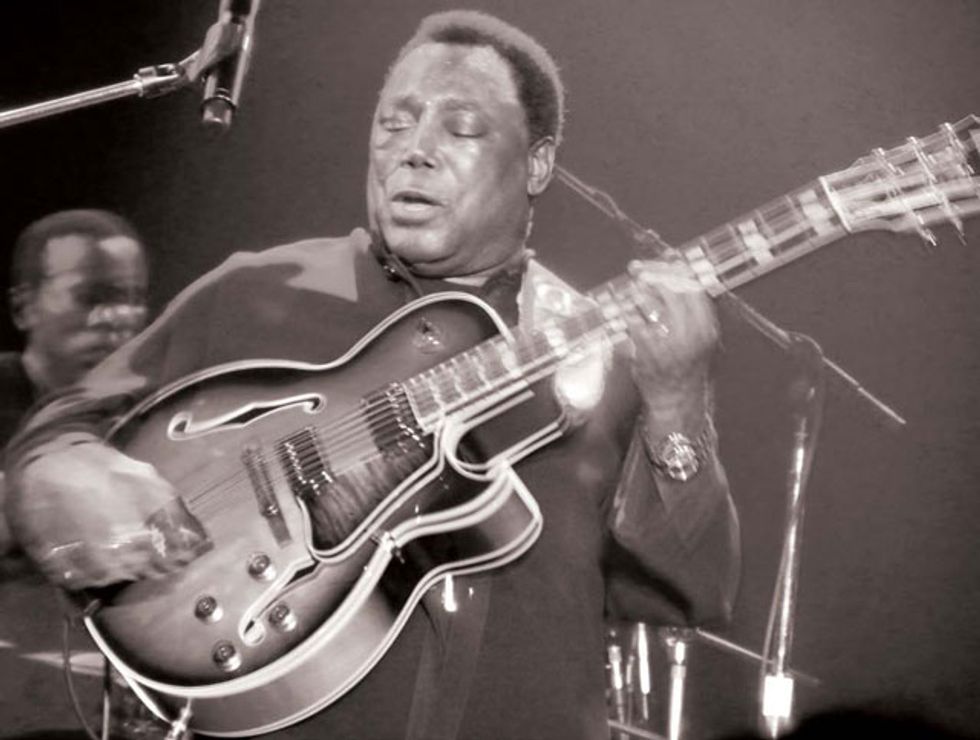

Photo by John Darwin Kurc

Photo by John Darwin KurcHow about amps?

I use two Fender Twins. I used

to use Polytone Mini-Brutes.

Although I love the tone—it’s

one of my favorite sounds for

guitar and works great in the studio—

I found that, in big places,

it wasn’t fast enough. It didn’t

give me instant sound. Now I’m

working with Fender and we’re

designing a new amplifier.

When is this coming out?

It’ll be out next year. We’re still

working on it now.

Will it be tube or solid-state?

That’s one thing we’re working

out. I lean toward the tubes,

because the sound is so much

more incredible. But I’m not

afraid to try solid-state.

Do you think the signature

amp will have a distortion

channel?

Man ... [laughs] I usually use

clean. But you did say something

important, though … I

better not take that feature out

of my new amp.

Guitar Man starts off with

“Tenderly,” which you also

recorded on the 1989 album

of the same name. Both are

solo-guitar renditions, but the

older version was a minute

longer and a bit flashier than

this new one.

I was trying to prove a point

[on the first one], like, “Here’s

what I can do.” I love that version,

because I surprised myself

on it. I was like, “Man, is that

me playing that?” But it wasn’t

very tender. This version recaptures

the romantic side of that

wonderful song. I was trying

to do a more romantic version

based on the Johnny Smith version.

He’s one of my favorite

players. Wes and I used to talk

about him all the time—how

beautifully he played and the

tuning down to D, which he

made popular back then.

Photo by John Darwin Kurc

Photo by John Darwin KurcWhen you tune down to D

and play the fast runs, do

you adjust your fingerings for

notes on the low E string or

do you just avoid that string?

If you make a mistake, baby,

you’re in the wrong place

[laughs]. It really doesn’t upset

the harmony too much, but you

turn a major chord into a blues

chord if you don’t watch it.

What prompted you to

record Stevie Wonder’s “My

Cherie Amour”?

I did it because I promised

Stevie I would. He had heard

me sing it once and he said,

“You gotta record that George.

You must record that.” I kept

my promise.

Guitar Man also features pop

songs like “The Lady in My

Life” and “Don’t Know Why.”

Pat Metheny also recorded

“Don’t Know Why” on his

2003 album One Quiet Night.

Are today’s pop songs becoming

the new standards?

Well, that’s the way they’ve

always done it. Miles Davis

did it. He used to do “Autumn

Leaves.” That wasn’t a jazz tune,

it was a pop song. When jazz

people do it, it takes on a whole

new meaning, different colors.

Sometimes they’ll reharmonize,

which really gives a lift to a

song that’s been overplayed.

Was “My One and Only

Love” inspired by the Johnny

Hartman/John Coltrane version?

Oh, definitely. That will always

remain an outstanding version

of that song and performance,

period. It was hard for me

to think about recording it,

because I didn’t want people to

think that we were stepping on

the toes of that version. I wanted

to pay homage to it, and I

think we did a decent job.

Photo by John Darwin Kurc

Photo by John Darwin KurcOn “Paper Moon,” your solo

starts off with some bending—

which isn’t often heard in a

straight-ahead jazz context.

Why do traditional jazz players

typically avoid bending notes?

If you remember, Charlie

Christian used to bend notes—

and he was the swingin’-est

cat there was, man! So I’m

not afraid. I think people are

used to hearing that in modern

music. You know, B.B. King

and all the other cats do it.

Rock players do it. I’m not

afraid to let jazz have a shot at

it again, too, since we started it.

Tell us about “Danny Boy.”

Well, first of all, I’ve got Irish

and Welsh blood in me. My

grandfather told me, “Yeah,

yeah, boy, you’re Irish and

Welsh.” That was my attempt

at creating some bagpipes, or

at least the vibe from bagpipes.

It worked very well because,

with some audiences, we see

people with tears in their eyes.

They must be Irish or Scottish

[laughs]. And when we play

in Ireland, people love us over

there. I played “Danny Boy”

over there for the first time a

few years ago, and I couldn’t

believe the response I got. It

was the best song in the show.

Mike Stern once told me,

“George Benson is the best

jazz guitar player alive.” Even

though you’re essentially a

pop star, this seems to be the

general consensus among

jazz guitarists.

Mike Stern’s a good cat, man. I

love him. I remember when he

came to New York, my manager

said, “Man, there’s a kid

in town—you gotta hear him

play.” So we went down and it

was Mike Stern. He bounced

off the wall—he took all the

paint off the wall in the place

that night! So I knew we had a

new star on our hands. He’s a

wonderful cat and he plays the

crap out of the guitar. You can’t

ask for more than that.

But Tal Farlow started it. They asked him who his favorite guitar player was, and he said, “George Benson,” and they said, “Why do you say that?” Because at the time, I was a pop artist and the kids didn’t like the fact that I was getting credit as a guitar player. And Tal Farlow said, “I like him because every time I hear him, he’s playing something new.” I think people like the fact that I keep coming up with new ideas—and they don’t have to be big ideas. Guitar players, they know. Once they hear you, they know your sound. When you play a lick, they know it’s you. “Man this sounds like George Benson, but I’ve never heard him play that before.” And that’s because I practice virtually every day. Still do.

Photo by Jerry L. Neff

Photo by Jerry L. NeffWhat kind of stuff do you

work on now?

Ideas mostly, things that people

have not heard. Like that thing

we did with “Danny Boy.” I

worked on that for a long time

before I got enough nerve to

bring it out. I’ve got a lot of different

formulas, and I use them

whenever they seem to fit. Say, for

instance, my solo on “Tequila.”

I started off playing nothing but

basic triads with an octave on top.

As simple as it sounds, in certain

circumstances it works very well.

Your technique is phenomenal.

In the beginning, what did

you work on to get it to such a

high level?

When I got to New York and

found all these guys with all this

fabulous technique—Pat Martino

and Grant Green and a few others—

I said, “Man, I’m not gonna

be able to make it here.” I knew

I couldn’t match those guys. So I

started devising my own method

and reexamined the fingerboard.

If you play a standard guitar,

where you’re playing across the

fingerboard, you’re playing down

the fingerboard instead of going

up. If I move my hands in the

direction, slide them up as I

play the notes, then it’s a logical

progression. That kind of thing.

I had to examine that over and

over again until I got it right. I’m

moving in the direction that the

sound is suggesting. It’s all about

getting from point A to point B.

So I said, “Well, let me try it this

way.” And I said, “Whoa! This

is much simpler—and I can be

much more accurate if I do it

this way.”

Musicians are also in awe of

your seemingly flawless sense

of time. Did you always have

that, or did you have to work

on it?

I listened to Charlie Christian

with the Benny Goodman

band. Benny Goodman rightfully

had the name “King

of Swing.” There were other

cats who could swing, but he

consistently swung and he

had good cats in the band. I

listened to that and realized

that I should loosen up a little

bit, leave myself room where

I could pick up some extra

things. Leave a note out here

and pick it up later over here—

add it to the swing. I began to

do it until it became natural,

and it’s followed me down

through the years.

Photo by John Darwin Kurc

Photo by John Darwin KurcWhat advice would you give

to players who want to develop

a stronger sense of time?

For example, some people recommend

using a metronome,

and others are completely

against it.

No, some people need that.

So it depends on the individual?

Yeah, well Montgomery used

it—I have the one that he used!

When I first saw him with that

metronome years ago, I said,

“Wow, Montgomery uses a

metronome! Is that why he’s so

good? Maybe I better get me a

metronome.” But I never used it.

I have a good sense of rhythm.

Your single-note playing is fairly

staccato, as opposed to, say,

Pat Metheny’s, which is very

legato. Is that something you do

intentionally? And if so, why?

I did it because my favorite

players play like that. Hank

Garland, he had a very staccatoy

sound. It made it sound

more forceful [scats staccato-ish

phrase]. It was like, “Wow, it’s

like the notes are dancing in

front of me!” I don’t have a lot

of pressure in my left hand, I

never did. I think it came from

playing cheap guitars where the

winding would come undone

on the strings and it would cut

my fingers. So I stopped pressing

hard. I play very light in my

left hand. Django, in order to

get the vibrato, had to have a

lot of pressure in his left hand.

Pat Martino has a lot of pressure

in his left hand.

You hold your pick at an

unconventional angle. Is there

an advantage to that?

There are advantages and disadvantages to every technique

I’ve seen. The technique that I

have lends itself toward playing

phrases that are not based in

numbers—y’know, eighth-notes,

16th-notes. It’s not based on

that. I’m leaving myself open so

I can change from quarter-notes

or eighth-notes and stick some

fast triplets in there. Instead of

playing four notes, if I play triplets

I get 12 [scats a triplet-infused

phrase]. But if you play with

standard technique—if you get

used to playing quarter-notes,

eighth-notes, 16th-notes, 32ndnotes,

whatever it is—you get

used to this [scats a fast phrase in

steady eighths], and after a while

that bores me. So the technique

I’m using—which isn’t the greatest,

don’t get me wrong—makes

it so I can play those phrases

and still be within the realm

of playing the single lines with

the quarter-notes or the even

eighth-notes.

Photo by Jerry L. Neff

Photo by Jerry L. NeffI imagine this technique is

fairly dependent on specific

picks or gauges, then.

I use medium picks. They’re not

too stiff and they allow me to

have better rhythm. And the two

edges [on mine] come down to a

point that’s straighter than on a

Fender pick. I do that because it

gives me much more snap when

the pick comes off the string.

Do you usually pick every

note, or do you integrate

hammer-ons and pull-offs

or sweep-picking in your

speedier lines?

There was a period when I

picked every note, but I find

that it’s not necessary in the

way I’m thinking now—I’m

beginning to let up on that.

As you get older, you don’t get

into the particulars so much

as you do when you’re trying

to speak a language. So I don’t

force that anymore. Kenny

Burrell asked me that once,

“George, are you picking every

note?” I said, “I don’t know—

I guess so, Kenny.” And he

was the master of the guitar.

He and Wes Montgomery

dominated the jazz world at the

time. So for him to ask me any

question about the guitar was

phenomenal.

George Benson's Gear

Top Right: Benson’s signature Ibanez hollowbodies

feature ornate, vintage-style headstock

inlays. Photo by John Mooy. Bottom Right: On his current tour, Benson has a guitar boat with two signature

Ibanez hollowbodies and a Yamaha nylon-string.

Photo by John Mooy. Left: Two of Benson’s Ibanez signature models—a GB200 (left) and a prototype of the upcoming LGB (Little Georgie Benson)—onstage with a pair of Fender

’65 Twin reissues mic’d with a large-diaphragm Shure condenser. Photo by John Mooy.

Top Right: Benson’s signature Ibanez hollowbodies

feature ornate, vintage-style headstock

inlays. Photo by John Mooy. Bottom Right: On his current tour, Benson has a guitar boat with two signature

Ibanez hollowbodies and a Yamaha nylon-string.

Photo by John Mooy. Left: Two of Benson’s Ibanez signature models—a GB200 (left) and a prototype of the upcoming LGB (Little Georgie Benson)—onstage with a pair of Fender

’65 Twin reissues mic’d with a large-diaphragm Shure condenser. Photo by John Mooy.Guitars

Ibanez LGB prototype,

Ibanez GB30, Yamaha

nylon-string, Cordoba

nylon-string

Amps

Two Fender 1965 Twin

Reverb reissues

Strings, Picks, and Accessories

Thomastik-Infeld George

Benson Signature .012s

(live) and .014s (studio),

Ibanez George Benson

mediums picks, Monster

Cable, Radial JDI Passive

Direct Box

Youtube It

For a taste of George Benson in action, check out

the following clips on YouTube.com.

Benson scat sings with Dizzy Gillespie,

then takes a jaw-dropping guitar solo

(from 7:48–8:58) that will make you

want to quit the guitar.

This rare clip shows Benson in a lessformal

setting, playing Miles Davis’ “So

What” with a killer band featuring drummer

Jeff “Tain” Watts and other notable

musicians. His killer solo starts at 5:25 and

features nearly three minutes of fretboardmelting

modal madness.

Benson makes his guitar sound like bagpipes

on this solo rendition of “Danny

Boy.” In addition to the chordal mastery

on display here, check out how Benson

articulates even the quickest of single-note

runs with his right-hand thumb—particularly

in the cadenza (3:00–3:08).

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)